This paper was first published in the Conference Booklet of the Republic of Korea Navy’s International Seapower Symposium held in Busan, S Korea, on 29 May 2025

Maritime Uncertainty at the Strategic Level

In our contemporary times, two broad systems are currently engaged in global competition. The first is a state system that draws its legitimacy from a consensually derived rules-based order. The second is a state system that seeks to disrupt this consensually derived rules-based order and supplant it with an international order whose rules are generated in an exclusive State, namely the People’s Republic of China. Thus, reflecting a desire to return to the “Middle Kingdom” period of Chinese hegemony, China is pushing for a global system of unipolarity that would be governed by rules formulated in Beijing — a system that would situate China as the keystone of all aspects of intra- and extra-regional affairs. In contrast, the USA has, thus far at least, advocated a system that sought to coordinate its own actions with those of major likeminded Indo-Pacific middle powers (e.g., Australia, India, Japan, South Korea, the UK, and Vietnam), contending that such a system was necessary to balance and counter China’s belligerent actions. This ongoing pull and push of these two systems is the fundamental cause of strategic uncertainty in the global maritime domain. However, the current political dispensation in the US — what we often refer-to as the second Trump administration — is injecting further uncertainty, by appearing to increasingly favour a world vision that is not one of great-power competition but of great-power collusion[1] — a system akin to the “Concert of Europe” of the 19th century.[2] Could Trump simply want a world managed by strongmen who work together — not always harmoniously but always purposefully — to impose a shared vision of “order” on the rest of the world? In other words, the present Trump administration has questioned whether middle powers such as Australia, India, Japan, South Korea, the UK, and Vietnam have any actual agency at all! India’s situation particularly interesting. Against the backdrop of the Russia-Ukraine conflict and the widespread condemnation of Russia by Western powers — with many of whom India is developing strong ties across multiple policy fields — New Delhi believes that the geopolitical constriction imposed upon India by China will be even more severely felt than before and, as a consequence, as former Indian diplomat, JN Misra has put it, India only “has bad and worse options to pick from”.[3] India, which shares an active border with China, must act to oppose any undue tightening of the Sino-Russian embrace, and is, therefore, reluctant to destroy its longstanding relationship with Russia. Arguably the most important feature of this relationship is India’s time-tested defence and diplomatic ties with Moscow, as Russia remains India’s largest arms supplier even though its share has dropped to 49% from 70% due to India’s robust efforts boost domestic defence manufacturing and to diversify its portfolio of defence imports.[4] As a case in point, the S-400 missile system has long been believed by New Delhi to be crucial to India’s needs of air defence and, indeed, this faith was fully born out when the S-400 was used by the Indian defence forces to extremely telling effect in Op SINDOOR, India’s very recent four-day (07 to 10 May 2025) and very intense military clash with Pakistan.[5] In Western minds at least, some degree of strategic uncertainty if not perplexity also exists when trying to rationalise India’s membership of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) and the BRICS construct against India’s obvious credentials as a vibrant democracy and an increasingly significant economy. This is largely an almost reflexive response to their mental positioning of Russia as a traditional adversary and a military threat, and of China as a more recently recognised one. It is this author’s view that such anxiety (and the strategic uncertainty that apparently arises in the wake of such anxiety) is wholly misplaced and stems from a cultural resistance to multipolarity in which Western powers are merely some poles amongst several others and not primus inter pares. Arguably the worst strategic nightmare for Europe (and North America) is to have to deal with an axis or a compact comprising China, Russia, North Korea, and perhaps Iran or even Turkey. India is the only power that can prevent or at least delay the cementing of such an axis, given that Russia is not talking ‘to’ Europe nor is Europe talking ‘to’ Russia. Both are talking ‘at’ each other, mostly because they are not in the same room (i.e., in the same organisations) so-to-speak. The only major power talking ‘to’ Russia is India. And if Russia is to talk ‘to’ India, it will do so only if India is (and is perceived by Moscow to be) a major power with adequate and evident strength all across the diplomatic, informational, military and economic (DIME) paradigm.[6] As this writer has often maintained, India must be strengthened and encouraged to engage with Russia in the SCO as well as in BRICS simply because India is the only “adult in the room”.[7] India’s unique position should then be leveraged and such leveraging will actually serve to reduce strategic uncertainty. A far more immediate and consequential cause of uncertainty is Türkiye. How should we think about Turkey under President Recep Tayyip Erdogan? Is Turkey the upholder of international law vis-à-vis the Montreux Convention[8] in the Black Sea or is it a major source of strategic disruption, letting out djinns of religious fanaticism from bottles that ought never to be uncorked?

Nowhere can this picture of strategic uncertainty be seen in sharper relief than in the Indo-Pacific, which is a predominantly — although certainly not exclusively — maritime space, stretching from the eastern shores of the continent of Africa to the western coasts of the Americas, and from Eurasia’s southern edge to the northern coastline of Antarctica. This region is well recognised as having been restored to its historical position being the centre of global socio-cultural and economic activity. Within its vastness, encompassing 64% of the world’s oceanic area, dwell half the world’s people in some 75 nation-states, accounting for nearly two-thirds of the world’s economy, and hosting seven of the world’s largest militaries. Along the many international shipping lanes (ISLs) that crisscross the Indo-Pacific flows 50% of global container traffic and 80% of global maritime oil shipments, negotiating some 65% of the world’s strategic maritime chokepoints (Hormuz, Bab-el-Mandeb, Mozambique Channel, Malacca, Sunda, Lombok, etc.).

Today, India’s ‘grand’ strategy, her ‘military’ strategy, and her ‘maritime’ strategy are all increasingly being contextualised to the Indo-Pacific. It is critical to recognise that for India — quite unlike for the USA — the Indo-Pacific is not in and of itself a ‘strategy’. It is, instead, a ‘strategic geography’ within which New Delhi formulates and executes a number of strategies.

“Strategic Geography” is a term that might need some explanation in the manner in which it differs from ‘real’ geography. If one were to take a chart or map that depicts ‘real’ geography and then place upon it a set of coordinates defined by specific latitudes and longitudes, such that they enclose or bound a given area, and, within the area that has been so ‘bounded’, if one were to then give special focus — at the national-level — in terms of the planning and execution of one’s geopolitical strategies, this enclosed or bounded area would define one’s ‘strategic geography’. Obviously, the strategic geography of one country can hardly be expected to be the same as that of another. Thus, the ‘strategic’ geography of, say, Tonga, will not be the same as that of, say, India. Likewise, the ‘strategic’ geography of, say, Sri Lanka, will not be the same as that of, say, South Korea, and that of Singapore will not be the same as that of Russia, and so on and so forth. Every country will have a strategic geography of its own and, since every State is sovereign, it enjoys untrammelled freedom to name its strategic geography whatsoever it chooses. In India’s case, the name that New Delhi has given to its strategic geography is the “Indo-Pacific”. The fact that its conceptualisation of the ‘Indo-Pacific’ might not be identical in shape and form to another country’s conceptualisation of its own strategic geography — which the latter might well have also named the ‘Indo-Pacific’ is of no great consequence. For instance, nobody believes that that every ‘John Smith’ must necessarily be defined by a physical shape and form that is identical to those of every other ‘John Smith’ simply because both of them have been given the identical name of ‘John Smith’! And yet, far too many people waste precious time in arguing why one sovereign country’s ‘Indo-Pacific’ differs from that of another (equally sovereign) country’s ‘Indo-Pacific’.

The ‘Indo-Pacific’ constructs of Japan, ASEAN, the EU, Netherlands, France, and Germany, coincide with that of India in that they include the entire region shaped by the Indian and the Pacific oceans, and, while those of Australia, Canada, and the USA do not presently go west of India and/or Pakistan, there is increasing evidence of ‘strategic convergence’ in their constructs. It must be noted that strategic convergence is not only about shared interests, which could, in their basest form, be simply transactional, but also shared values, ideas, and norms, across various policy-fields. New Delhi finds that strategic convergence with its partners is increasingly found in a variety of policy-fields. The sheer ‘number’ of these policy fields and the ‘depth’ of strategic convergence across them gives rise to a hierarchy of ‘Strategic Partnerships’, which was first articulated, albeit with fairly-limited numbers, by scholars from New Delhi’s “Foundation for National Security Research”, in November of 2011.[9] The formulation has, over the past decade-and-a-half or thereabouts, been steadily gaining traction as an alternative to the US-led treaty alliances of the Cold War period (incorporating, within the Indo-Pacific, Japan, South Korea, Thailand, the Philippines, Australia, and New Zealand). The current hierarchy is depicted in Figure 1.

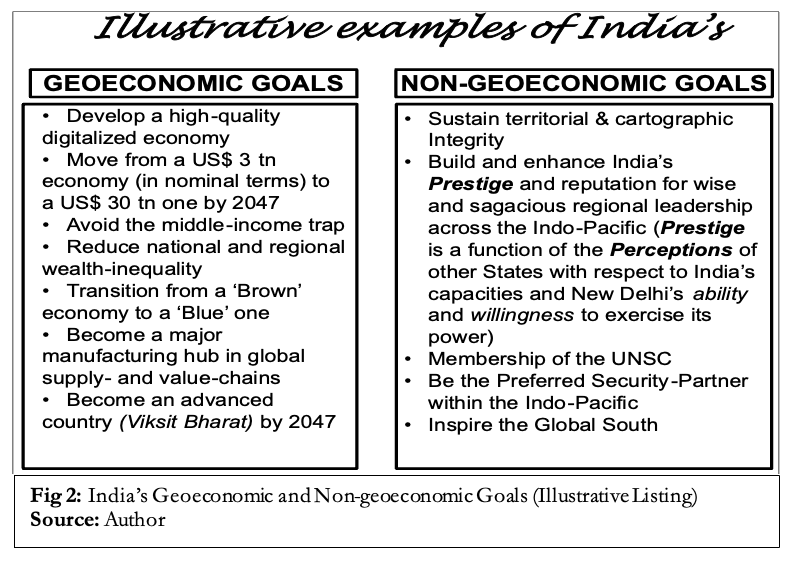

To reiterate, the Indo-Pacific is, for India, a ‘strategic geography’ within which New Delhi seeks to formulate and execute a number of ‘strategies’. Obviously, each ‘strategy’ reflects New Delhi’s endeavour to attain one or another goal, be this a geoeconomic goal or a non-geoeconomic one. Insofar as India is concerned, an illustrative listing (but certainly not an exhaustive one) of the geoeconomic goals, as also the non-geoeconomic ones, that its strategies, contextualised to its conceptualisation of the Indo-Pacific, seek to attain, are indicated in Figure 2:

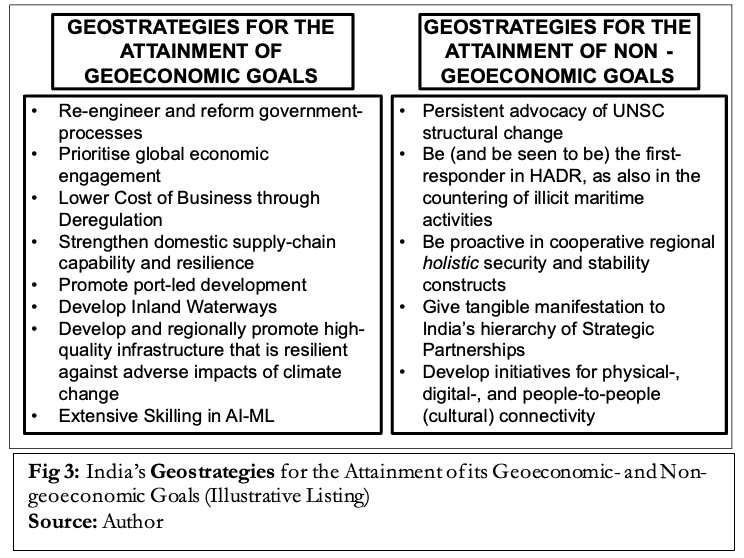

To attain the geoeconomic and non-geoeconomic goals depicted above, India formulates a series of geostrategies. Before going any further, it may be prudent to recall the difference between a ‘strategy’ and a ‘plan’: A ‘plan’ will always address questions such as “What is to be done?”, “How is to be done”, “Who is to do it?”, “Where does it have to be done?”, “When does it have to be done?”, “For how long does it have be done?”, and so on. A ‘strategy’, on the other hand, must not only provide answers to these very same questions, but in addition, must answer the critical question, “Why is it being done?”. If a strategy does not answer the question ‘Why’, it could, indeed, be many wonderful things, but is not a ‘strategy’. In addition, of course, a ‘strategy’ will often contain numerous subordinate ‘plans’ that are spread over space and time. It is also important to note that ‘strategic’ is an adjective and cannot exist without its noun, namely, ‘strategy’. To illustrate, India does not, in and of itself, have a ‘strategic geography’. It simply has a ‘geography’. Only if it has a ‘strategy’ that seeks to leverage this geography will India have a strategic geography. The same is true for South Korea or, indeed, for any (and every) other country. Far too often, one encounters the bald statement that such-and-such country has a ‘strategic’ location or a ‘strategic’ geography without there being any evidence of that country having formulated a ‘strategy’ to leverage its location or geography!

An illustrative sampling of the geostrategies that New Delhi is formulating for the attainment of the geoeconomic and non-geoeconomic goals that had been depicted in Figure 2, is depicted in Figure 3:

While executing these strategies, New Delhi remains acutely aware that India is not a post-modern State and that its geographical borders remain contested. The fundamental cartographic identity of the geopolitical entity called India, as also its territorial integrity, are, therefore, matters of very great sensitivity. New Delhi recognises that India’s cartographic identity and its territorial integrity will always demand the acquisition and exercise of ‘land’ and ‘aerospace’ power (as so vividly depicted in the recently conducted and hugely successful Op SINDOOR),[10] and yet, India holds to the belief that the next two centuries will be centuries of the ‘sea’ and of ‘space’ and, therefore, over the course of these two centuries India will either be a ‘maritime’ power and a ‘space’ power, or she will not be any kind of power at all! Consequently, India’s strategic challenge will always be one of achieving the right balance between her ‘maritime’ and her ‘land-based’ geopolitical imperatives in this era of geopolitical uncertainty.

While executing these strategies, New Delhi remains acutely aware that India is not a post-modern State and that its geographical borders remain contested. The fundamental cartographic identity of the geopolitical entity called India, as also its territorial integrity, are, therefore, matters of very great sensitivity. New Delhi recognises that India’s cartographic identity and its territorial integrity will always demand the acquisition and exercise of ‘land’ and ‘aerospace’ power (as so vividly depicted in the recently conducted and hugely successful Op SINDOOR),[10] and yet, India holds to the belief that the next two centuries will be centuries of the ‘sea’ and of ‘space’ and, therefore, over the course of these two centuries India will either be a ‘maritime’ power and a ‘space’ power, or she will not be any kind of power at all! Consequently, India’s strategic challenge will always be one of achieving the right balance between her ‘maritime’ and her ‘land-based’ geopolitical imperatives in this era of geopolitical uncertainty.

Within the vast maritime expanse of the Indo-Pacific, India’s principal ‘maritime-security’ interest has been articulated at the prime ministerial level and is the attainment of ‘holistic’ maritime security which has been defined as “freedom from threats arising ‘in’ the sea or ‘through’ the sea or ‘from’ the sea.[11] Figure 4 depicts this typology schematically:

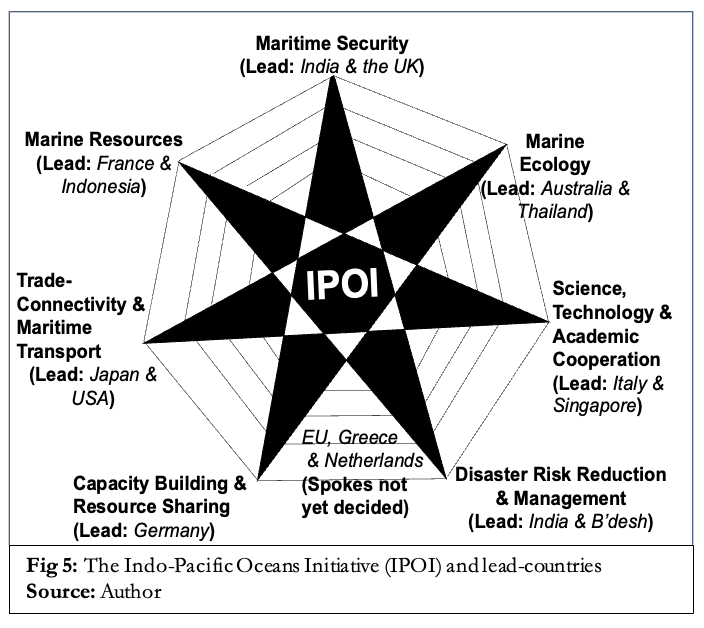

The adjective ‘holistic’ cannot be stressed strongly enough. It even finds prominent mention in India’s recently evolved and recalibrated maritime policy, which is encapsulated in the acronym MAHASAGAR (Mutual and Holistic Advancement for Security and Growth Across Regions). While on an official visit to Mauritius in March of 2025, India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced this evolved avatar of India’s maritime policy, which has now replaced the earlier maritime policy-acronym SAGAR (Security and Growth for All in the Region).[12] MAHASAGAR retains the regional emphasis of SAGAR but extends its strategic focus to encompass not only subsume India’s expansive conceptualisation of the Indo-Pacific but also the wider Global South, reinforcing India’s commitment to equitable maritime cooperation, inclusive growth, and capacity building across regions. The Government of India has accordingly framed MAHASAGAR as a guiding doctrine[13] for its maritime endeavours. Importantly, the Indo-Pacific Oceans Initiative (IPOI) — a non-treaty-based, voluntary initiative aimed at promoting cooperation for a free, open, and rules-based Indo-Pacific region — continues to provide first-order specificity to this maritime policy/doctrine. The IPOI, as depicted in Figure 5, identifies seven major maritime lines-of-thrust. Although the Government of India’s Ministry of External Affairs has described these as seven “pillars”, they are better depicted as deeply interconnected web of seven spokes, with each soke representing a maritime line-of-thrust. Countries located in the Indo-Pacific those operating within it, as well as those with significant interests in this regional space, have been encouraged to step-up and take the lead in one or more of these maritime lines-of-thrust. The concept has gained considerable traction since its first articulation by India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi on 04 November 2019, while addressing the 14th East Asia Summit in Bangkok, and the current situation in terms of countries that have agreed to lead specific maritime lines-of-thrust are also indicated in Figure 5.

The adjective ‘holistic’ cannot be stressed strongly enough. It even finds prominent mention in India’s recently evolved and recalibrated maritime policy, which is encapsulated in the acronym MAHASAGAR (Mutual and Holistic Advancement for Security and Growth Across Regions). While on an official visit to Mauritius in March of 2025, India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced this evolved avatar of India’s maritime policy, which has now replaced the earlier maritime policy-acronym SAGAR (Security and Growth for All in the Region).[12] MAHASAGAR retains the regional emphasis of SAGAR but extends its strategic focus to encompass not only subsume India’s expansive conceptualisation of the Indo-Pacific but also the wider Global South, reinforcing India’s commitment to equitable maritime cooperation, inclusive growth, and capacity building across regions. The Government of India has accordingly framed MAHASAGAR as a guiding doctrine[13] for its maritime endeavours. Importantly, the Indo-Pacific Oceans Initiative (IPOI) — a non-treaty-based, voluntary initiative aimed at promoting cooperation for a free, open, and rules-based Indo-Pacific region — continues to provide first-order specificity to this maritime policy/doctrine. The IPOI, as depicted in Figure 5, identifies seven major maritime lines-of-thrust. Although the Government of India’s Ministry of External Affairs has described these as seven “pillars”, they are better depicted as deeply interconnected web of seven spokes, with each soke representing a maritime line-of-thrust. Countries located in the Indo-Pacific those operating within it, as well as those with significant interests in this regional space, have been encouraged to step-up and take the lead in one or more of these maritime lines-of-thrust. The concept has gained considerable traction since its first articulation by India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi on 04 November 2019, while addressing the 14th East Asia Summit in Bangkok, and the current situation in terms of countries that have agreed to lead specific maritime lines-of-thrust are also indicated in Figure 5.

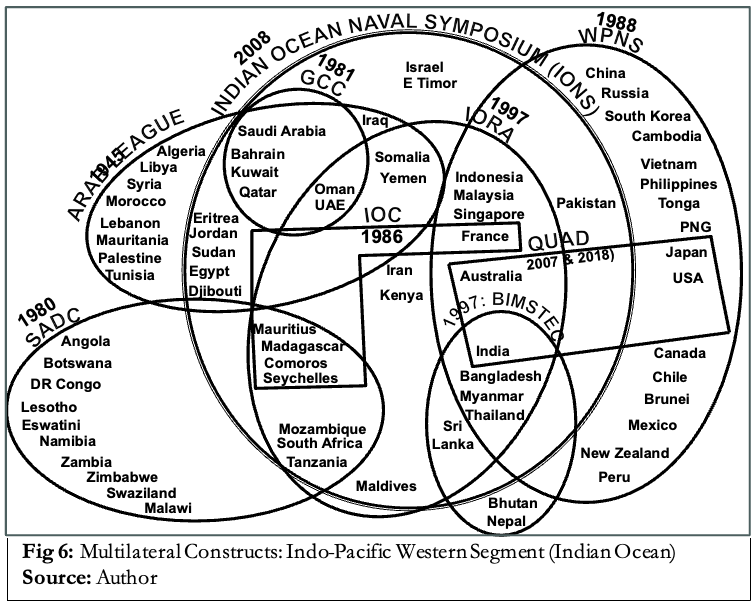

India’s maritime strategies, much like those of any major maritime power, span the environmental conditions of peace, tension, and conflict. In times of peace, India’s fundamental maritime strategy is one of ‘constructive engagement’. New Delhi is currently concentrating upon five major — but very different — approaches for its endeavours vis-à-vis ‘Constructive Engagement’. The first is through multilateral constructs. India has been assiduously contributing to a series of overlapping multilateral constructs in the western segment of the Indo-Pacific, i.e., the Indian Ocean, as may be seen schematically in Figure 6:

India’s maritime strategies, much like those of any major maritime power, span the environmental conditions of peace, tension, and conflict. In times of peace, India’s fundamental maritime strategy is one of ‘constructive engagement’. New Delhi is currently concentrating upon five major — but very different — approaches for its endeavours vis-à-vis ‘Constructive Engagement’. The first is through multilateral constructs. India has been assiduously contributing to a series of overlapping multilateral constructs in the western segment of the Indo-Pacific, i.e., the Indian Ocean, as may be seen schematically in Figure 6:

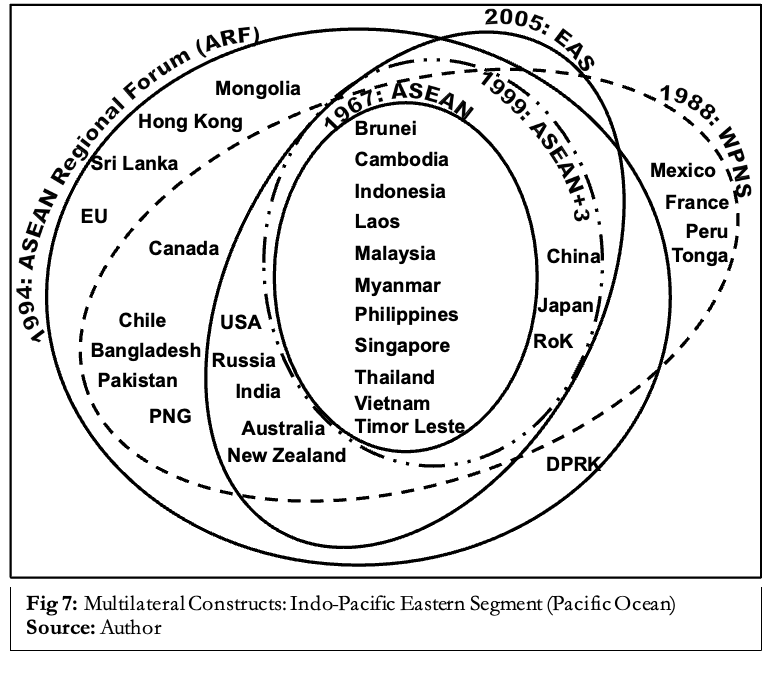

In the eastern segment of the Indo-Pacific (the Pacific Ocean), too, India is included in all ASEAN-led constructs (other than the “ASEAN+3”) as Figure 7 depicts:

In the eastern segment of the Indo-Pacific (the Pacific Ocean), too, India is included in all ASEAN-led constructs (other than the “ASEAN+3”) as Figure 7 depicts:

India’s second strategic approach is the “Indo-Pacific Oceans Initiative” (IPOI), mentioned and schematically depicted in Figure 5 above. It is important to reiterate that the IPOI has been envisaged as an open, non-treaty-based global initiative aimed at cooperatively addressing maritime challenges that the international community faces in the Indo-Pacific. It is not some ‘grand plan’ of India’s that may be accepted or rejected or joined or left. It merely asks nations to cooperatively and collaboratively address the seven maritime lines of thrust that need to be addressed if mutual security, enduring stability, and inclusive, sustainable growth are to be achieved — all three of which are crucial prerequisites to lasting peace and prosperity.

India’s second strategic approach is the “Indo-Pacific Oceans Initiative” (IPOI), mentioned and schematically depicted in Figure 5 above. It is important to reiterate that the IPOI has been envisaged as an open, non-treaty-based global initiative aimed at cooperatively addressing maritime challenges that the international community faces in the Indo-Pacific. It is not some ‘grand plan’ of India’s that may be accepted or rejected or joined or left. It merely asks nations to cooperatively and collaboratively address the seven maritime lines of thrust that need to be addressed if mutual security, enduring stability, and inclusive, sustainable growth are to be achieved — all three of which are crucial prerequisites to lasting peace and prosperity.

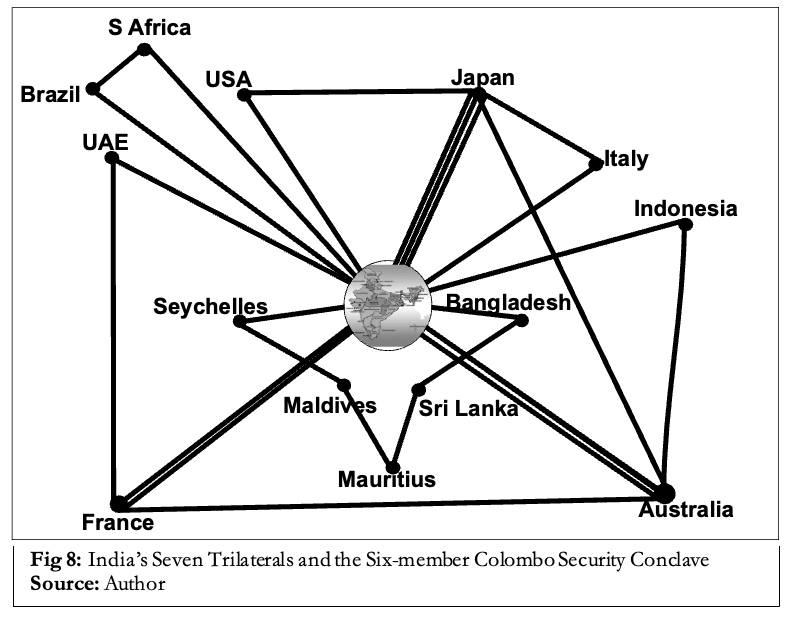

India’s third approach is through ‘minilaterals’ such as the “Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation” (BIMSTEC); the “Forum for India-Pacific Islands Cooperation” (FIPIC), which India established in 2014 and which includes 14 of the island countries – Cook Islands, Fiji, Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Micronesia, Nauru, Niue, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tonga, Tuvalu, and Vanuatu;[14] and the six members of the “Colombo Security Conclave” — India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Maldives, Mauritius and Seychelles. Also embedded within this third approach are seven trilaterals as depicted in Figure 8:

India’s fourth approach is the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad) and its several capacity-building and capability-enhancement endeavours. India believes that perhaps the best way to sustain a stable, consensually derived rules-based order across the length and breadth of the Indo-Pacific is for the QUAD to weave the regional fabric through cooperative economic frameworks, quality infrastructure, comprehensive maritime domain awareness, and collective Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief (HADR) Partnerships, health security, climate change and clean energy transition. The Quad is making progress and the sixth Quad Leaders’ Summit held in Wilmington, Delaware, on 21 September 2024 was of particular significance, as summarised by Captain KS Vikramaditya, Senior Fellow at the National Maritime Foundation (NMF) when he wrote:

India’s fourth approach is the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad) and its several capacity-building and capability-enhancement endeavours. India believes that perhaps the best way to sustain a stable, consensually derived rules-based order across the length and breadth of the Indo-Pacific is for the QUAD to weave the regional fabric through cooperative economic frameworks, quality infrastructure, comprehensive maritime domain awareness, and collective Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief (HADR) Partnerships, health security, climate change and clean energy transition. The Quad is making progress and the sixth Quad Leaders’ Summit held in Wilmington, Delaware, on 21 September 2024 was of particular significance, as summarised by Captain KS Vikramaditya, Senior Fellow at the National Maritime Foundation (NMF) when he wrote:

“The joint statement released at the end of the summit, now being referred to as the “Wilmington Declaration”,[15] provides a roadmap for the Quad’s unified approach to maritime security, upholding international law, and addressing threats through joint initiatives. Emphasising the principles of peace, stability, and cooperation, the declaration highlights several areas that are critical for sustaining the Indo-Pacific’s security architecture, including support for the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), capacity-building for regional maritime partners, and technological investments in surveillance, and infrastructure resilience. Since the Indo-Pacific is primarily (although not exclusively) a maritime geography, it is only natural that the primary focus of the Quad’s varied endeavours remains maritime.”[16]

Within maritime security, ongoing endeavours of the Quad are concentrating upon the Indo-Pacific Partnership for Maritime Domain Awareness (IPMDA). Although it is important for the Quad to address the twin issues of “maritime situational awareness” (MSA) and “maritime domain awareness” (MDA), this does not appear to be happening, and this lack of conceptual clarity could become significant in the future. This notwithstanding, since the programme’s inception, the IPMDA has expanded its network across various regional hubs, including the Pacific Islands Forum Fisheries Agency (PIFFA) and the Information Fusion Centre for the Indian Ocean Region (IFC-IOR). By providing its partner countries (not just its members) with real-time, integrated information, the Quad enhances their ability to enforce maritime laws within their waters. Prospective collaboration includes the sharing of satellite data, training in data analysis, and integration with local coast guard and naval operations.[17] Further, over the coming year, Quad partners intend to layer modern technology and data into the IPMDA, thereby continuing to deliver cutting-edge capability and information to the region.

The fifth and final approach being adopted by India in terms of constructive engagement is that of promoting connectivity in general and maritime connectivity in particular. It is very important that specificities be injected into deliberations about maritime connectivity. At least six aspects require far greater granularity than is presently being afforded. These are: (1) the ports or nodes that are sought to be connected; (2) the medium upon which this connectivity is sought to be maintained; (3) the platforms that are intended to move between the identified ports and upon the identified medium; (4) the commodities (cargo, human beings, data-packets or data-streams) that would be carried by the identified platforms; (5) the ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ infrastructure that needs to be established and sustained, and (6) the rules-based legal instruments, the security and safety norms, procedures, and processes, etc., which are necessary to support the envisaged maritime connectivity.

A few words about ‘hard’/ ‘military’ security may be in order at this juncture. Beyond the outer limit of India’s Legal Continental Shelf, the Indian Navy is the sole maritime manifestation of the sovereign power of the Republic of India. Given that the Indo-Pacific is a predominantly maritime space, the Indian Navy is India’s option of choice for the undertaking of stabilising and shaping operations, largely through naval diplomacy designed to signal national intent, as also to reassure, dissuade, and deter wherever appropriate and necessary. In many ways, “Reassurance” is the converse of “Deterrence” in that the former seeks to convince an ally or partner that it will, indeed, be supported in the face of coercion or aggression, but like deterrence, the success of reassurance is crucially dependent upon perceptions of capacity, capability, and resolve.

Where India and her navy are concerned, even amidst the rapidly changing dynamics of the Indo-Pacific, as described thus far, there are three great constants. The first is that India’s principal national interest remains the economic, material, and societal wellbeing of the people of India. The second is that as a maritime nation, India’s principal maritime interest remains freedom from threats arising in the sea or from the sea or through the sea as already depicted in Figure 4 above. The third is that India’s eight principal maritime objectives remain unchanged, namely: (1) protection from sea-based threats to India’s territorial integrity; (2) Stability (peace & prosperity) in India’s maritime neighbourhood; (3) the creation, development, and sustenance of a ‘Blue’ Economy that is resilient against adverse maritime effects of climate-change; (4) the preservation, promotion, pursuit and protection of offshore infrastructure and maritime resources within and beyond the Maritime Zones of India (MZI); (5) the promotion, protection and safety of India’s overseas and coastal seaborne trade including her Sea Lines of Communication (SLOCs), and, the ports that constitute the nodes of this trade; (6) support to marine scientific research, including that in Antarctica and the Arctic; (7) the provision of support, succour, and extrication-options to the Indian diaspora; and (8) obtaining and retaining a favourable geostrategic maritime-position.[18]

India’s maritime-security strategies within the Indo-Pacific are informed by a continuous assessment of present and future risk in the region. Risk, of course, is a balance between probability of occurrence of an event versus the acceptability of resultant loss should the event occur. India identifies seven major maritime risks: (1) risks to territorial integrity, (2) geopolitical constriction, (3) risks concerning trade-dependence and disruptions, (4) risks arising from the security-impacts of climate change, (5) risks involving illicit maritime activities (including terrorism, piracy, and various forms of maritime crime), (6) risks of disruptions to maritime supply chains, especially those involving energy supplies, (7) risks of inter-State conflict.

Moving on from risk, India, like all other countries, also assesses maritime security ‘threats’, where threat is the multiplication of military capacity-and-capability and aggressive intent.[19] Unsurprisingly, only two countries emerge as serious military threats to India— China and Pakistan. Details of how India and its navy intend to deter — if deterrence proves unsuccessful — militarily deal with these threats should they manifest themselves as clear and present dangers, is outside the scope of this paper. Suffice it to say that Naval Headquarters in New Delhi is fully in sync with other organs of the Indian defence forces and — since conflict is waged by States through actions by military forces amongst others — with the whole of the nation.

Before concluding, it is germane to state that as might be expected in a region that is pivotal to global industries including manufacturing, technology, finance, energy, agriculture, fishing, tourism, and shipping, security within the Indo-Pacific is a direct function of the acceptance, robustness, and durability of a rules-based maritime order. It is important to note that a consensually derived rules-based maritime order, as we know it, is the outcome of a complex web of public international maritime law (PIML) frameworks involving a whole slew of international conventions/treaties which, taken in aggregate, establish overarching principles and standards that govern the activities and behaviour of a large variety of maritime entities, whether these are operating upon the sea or are being controlled and managed from locations upon the land. Unfortunately, far too many people believe that it is solely the 1982 “United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea” (UNCLOS 1982) that is the determinant of this rules-based maritime order. However, it is critical to recognise that the rules-based maritime order is an amalgam of UNCLOS 1982 and a whole slew of extremely important international conventions, such as the “Convention on the International Maritime Organization” (IMO Convention), the “Convention for the Suppression of Unlawful Acts against the Safety of Maritime Navigation” (SUA Convention), the “Convention on the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea, 1972” (COLREGS), the “International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea” (SOLAS Convention), the “International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships” (MARPOL Convention), the “International Convention on Standards of Training, Certification and Watchkeeping for Seafarers” (STCW Convention), the “Constitution and Convention of the International Telecommunication Union” (ITU Convention), the FAO “Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries”, the “Agreement on Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction” (BBNJ Treaty), etc.

******

About the Author

Vice Admiral Pradeep Chauhan, AVSM & Bar, VSM, IN (Retd), is the Director-General of the National Maritime Foundation (NMF), New Delhi, India. He is a prolific writer and a globally renowned strategic analyst who specialises in a wide range of maritime affairs and related issues. He may be contacted at directorgeneral.nmfindia@gmail.com

Endnotes:

[1] Stacie E Goddard, “The Rise and Fall of Great-Power Competition: Trump’s New Spheres of Influence”, Foreign Affairs, 22 April 2025, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/rise-and-fall-great-power-competition

[2] Encyclopaedia-Britannica (Politics, Law & Government, International Relations, European history), 09 May 2025, https://www.britannica.com/event/Congress-of-Vienna

[3] Vikas Pandey, “Ukraine: Why India is not Criticising Russia over Invasion”, BBC News (Online), 03 March 2022,

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-60552273

[4] Ibid

[5] Government of India, Press Information Bureau, Ministry of Defence Press Release, “Operation SINDOOR: India’s Strategic Clarity and Calculated Force”, 14 May 2025, https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleseDetail.aspx?PRID=2128748

[6] US Department of Defense Joint Publication 1, “Doctrine for the Armed Forces of the United States”, https://irp.fas.org/doddir/dod/jp1.pdf

[7] James Mann, “The Adults in the Room”, The New York Review, 26 October 2017 Issue, https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2017/10/26/trump-adult-supervision/

[8][8] Adam Zeidan, “Montreux Convention”, Encyclopaedia-Britannica (Politics, Law & Government, International Relations, European history), https://www.britannica.com/event/Montreux-Convention

See Also: Republic of Türkiye, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Implementation of the Montreux Convention”, https://www.mfa.gov.tr/implementation-of-the-montreux-convention.en.mfa

[9] Satish Kumar, SD Pradhan, Kanwal Sibal, Rahul Bedi and Bidisha Ganguly, “India’s Strategic Partners: A Comparative Assessment”, Foundation for National Security Research

New Delhi, November 2011

[10] Op Cit (Spra Note 5), Government of India, Ministry of Defence Press Release, “Operation SINDOOR…”, 14 May 2025, https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleseDetail.aspx?PRID=2128748

[11] Address by the late Dr Manmohan Singh, erstwhile Prime Minister of India, inaugurating the Indian Ocean Naval Symposium (IONS) Seminar at New Delhi, 14 February 2008, http://archivepmo.nic.in/drmanmohansingh/speech-details.php?nodeid=633

[12] Government of India, Ministry of External Affairs. “Prime Minister Narendra Modi Unveils MAHASAGAR Vision in Mauritius.” March 2025. https://www.mea.gov.in/press-releases.htm.

[13] Unlike militaries, which distinguish between the terms “doctrine” and ‘policy”, civilian echelons in many governments tend to use these two terms as synonyms

[14] Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, Business Accelerator for Forum for India – Pacific Islands Cooperation (FIPIC), “About FIPIC”, https://fipic.ficci.in/about.html

[15] Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, “The Wilmington Declaration Joint Statement from the Leaders of Australia, India, Japan, and the United States” Media Centre, 21 September 2024. https://www.mea.gov.in/bilateral-documents.htm?dtl/38320/

[16] Captain KS Vikramaditya, “The Wilmington Declaration — Charting India’s Role in a Resilient and Cooperative Indo-Pacific”, NMF Website, 25 December 2024, https://maritimeindia.org/the-wilmington-declaration-charting-indias-role-in-a-resilient-and-cooperative-indo-pacific/

[17] David Brewster, Simon Bateman, “Maritime Domain Awareness 3.)”, Australian National University, National Security College, Report, September 2024. https://nsc.anu.edu.au/sites/default/files/2024-10/WEB%20UPDATED_NSC_MDA_Report_2024_V2_0.pdf

[18] Vice Admiral Pradeep Chauhan, “India’s Proposed Maritime Strategy”, National Maritime Foundation Website, February 3, 2020. https://maritimeindia.org/indias-proposed-maritime-strategy/

[19] Tomohide Murai, “Threats come from Revisionist Neighbors”, East Asian Maritime Security, Vol 12, 30 December 2024, Research Institute for Peace and Security (RIPS), Japan, rips-newsletter@rips.or.jp

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!