Under India’s presidency, the G20 forum achieved an important milestone in the global discourse on Blue Economy. A striking example was the “Chennai High-Level Principles for a Sustainable and Resilient Blue/Ocean-based Economy”,[1] unanimously adopted by G20 members at the meeting of Environment and Climate Ministers, which was held in Chennai in July 2023. This unique document provides a set of fundamental principles that can guide further development of national-level strategies and policies on Blue Economy by G20 members and other countries as well, on a voluntary basis, as per national circumstances and priorities.

The Ministerial Meeting of the Environment and Climate Sustainability Working Group (ECSWG) was chaired by the Hon’ble Minister of Environment, Forest and Climate Change of the Government of India, Shri Bhupender Yadav. The meeting saw active participation from 41 Ministers and their deputies from the G20 members and invited countries. The “Outcome Document” and “Chair Summary” of the Environment and Climate Sustainability Working Group were released at the meeting wherein the Chennai High-Level Principles for a Sustainable and Resilient Blue/Ocean-based Economy were appended as an Annex. Ten Presidency Documents were also released during the meeting, and these provided best practices and knowledge-inputs on several themes related to land restoration, biodiversity conservation, water management, marine plastic litter, blue economy, circular economy, and resource efficiency.

Indian G20 Presidency’s contribution to the discourse on Blue Economy

Historically, most international forums (including the G20) have dealt with issues related to the ocean and the Blue Economy in a somewhat disjointed manner, as a subset of broader discussions on climate change, biodiversity conservation or sustainable development. It was only in 2020 that the first dedicated Ocean and Climate Change dialogue was held under the aegis of the UNFCCC, while the first dedicated UN Ocean Conference was held only in 2017.

In contrast, the G20 has been far more active. G20 deliberations on ocean-related issues began soon after the “Rio+20 Conference” held in 2012. At the Hamburg G20 Summit in 2017, under the German Presidency, G20 members adopted the “G20 Action Plan on Marine Litter”. Building on that momentum, the “G20 Implementation Framework for Actions Against Marine Plastic Litter” was established in 2019 under the Japanese Presidency. In the same year, the G20 also agreed upon the “Osaka Blue Ocean Vision” and committed to reduce additional pollution by marine plastic litter to zero by 2050. In 2020, the G20 took an important step towards the conservation and restoration of coral reefs with the launch of the “Coral Research and Development Accelerator Platform” (CORDAP) under the Saudi Arabian Presidency. Last year, in 2022, under the Indonesian Presidency, the “Ocean 20 Launch Event” was conducted in Bali to discuss ocean related issues in a comprehensive manner.

The Indian Presidency, in 2023, took the metaphoric baton from Indonesia and conducted the “Ocean 20 Dialogue” in Mumbai, where cross-cutting themes of science, technology and innovation, policy and governance, and sustainable blue finance, were discussed in great detail. For the first time in the history of G20, the “Blue Economy” was added as a dedicated priority agenda point within the Environment and Climate Sustainability Working Group (ECSWG), under the Indian Presidency, to deliberate upon challenges and opportunities associated with the sustainable and equitable utilisation of coastal and marine resources. This epitomises India’s commitment to elevate issues related to ocean health and the Blue Economy within the ongoing international discourse on the environment and sustainable development.

The “High-Level Principles for Blue/Ocean-based Economy” were developed through a comprehensive consultative process, which involved the active participation of the G20 member-States, invited countries, and international organisations, during all four ECSWG meetings and several virtual meetings as well. In addition to the “High-Level Principles”, the Indian Presidency also produced two major knowledge outputs relevant to the Blue Economy, namely, a technical study on “Accelerating the Transition to a Sustainable and Resilient Blue Economy”, jointly produced by the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), and the 5th edition of the G20 Report on “Actions Against Marine Plastic Litter”, produced by the Ministry of Environment Forest and Climate Change and supported by the Ministry of Environment of Japan.

Distinguishing Between “Blue Economy” and “Ocean Economy”

Traditionally, the ocean and its ecosystems have been viewed as sources of limitless resources and cost-free spaces to dispose-off waste, resulting in excessive use and, in some cases, irreversible changes to the coastal and marine environments. The term “Ocean Economy” has been conventionally used as an umbrella term to refer to all economic activities that take place in the coastal and marine spaces, including activities such as shipping and transportation, offshore oil and gas exploration, marine tourism and recreation, fisheries and aquaculture, marine renewable energy, and marine biotechnology. The Ocean Economy primarily emphasises the economic value generated by these activities, together with the goods and services, regardless of their impacts on the coastal and marine environments.

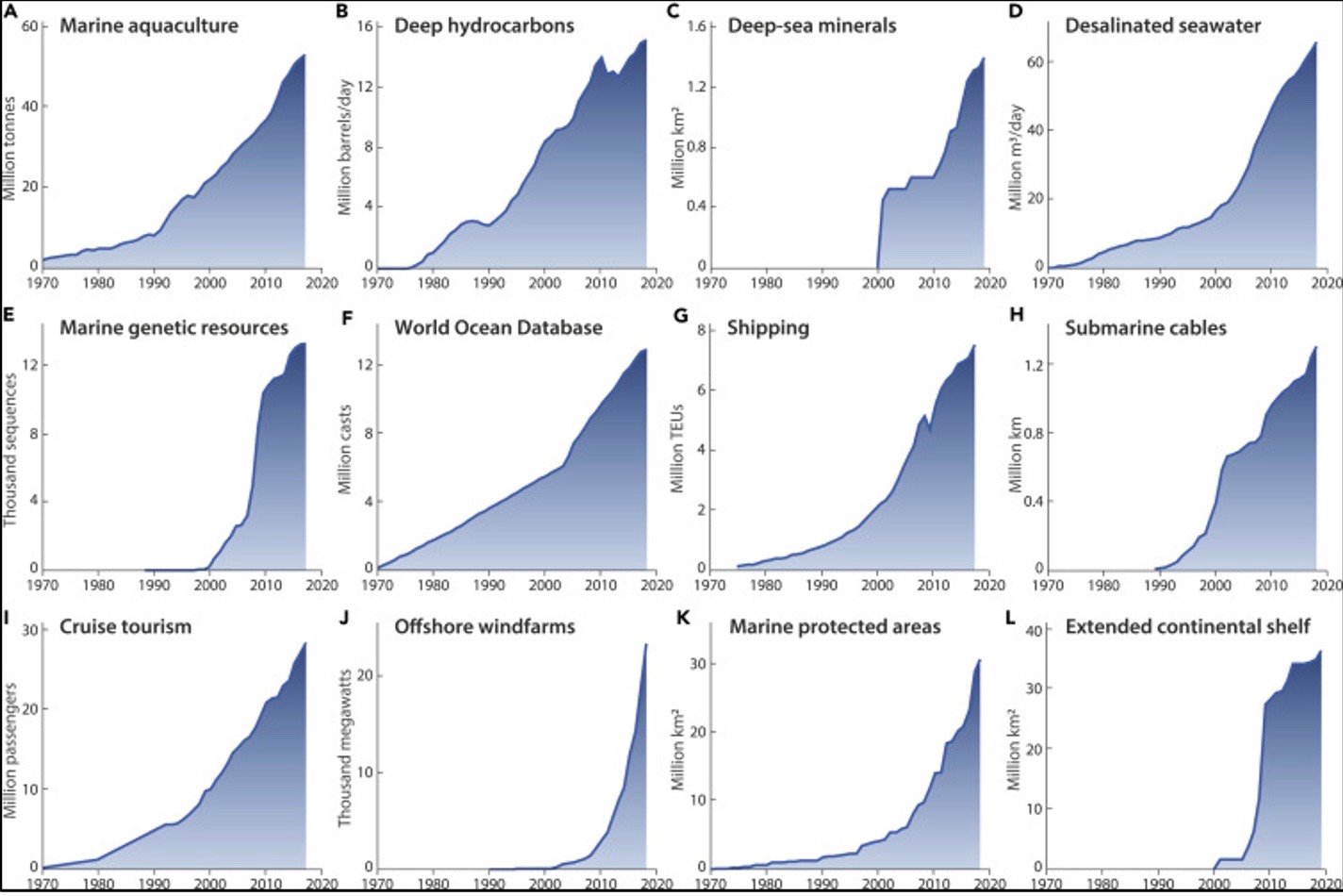

A 2020 study showed that nearly all of these economic activities have shown remarkable rates of growth in the last 50 years, with a sharp increase at the onset of the twenty first century — a phenomenon that is frequently referred-to as ‘blue acceleration’.[2] This can be attributed to a growing realisation by countries of the economic opportunities provided by the ocean space. Figure 1 depicts these trends in respect of marine aquaculture production, deep offshore hydrocarbon extraction, deep-sea mining for minerals, seawater desalination capacity, marine genetic resources, accumulated number of casts added to the “World Ocean Database”, containerised port-traffic, the total length of submarine fibre-optic cables, cruise-ship tourism (number of cruise passengers), installed offshore wind energy capacity, marine protected areas, and areas of the seabed claimed as the extended continental shelf.

Figure 1: The Blue Acceleration.

Source: J B Jouffray, R Blasiak, A V Norstrom, H Osterblom, and M Nystrom, “The Blue Acceleration: The Trajectory of Human Expansion into the Ocean”, One Earth Perspective No 2, 2020.

Unfortunately, yet predictably, this acceleration in economic activity has been accompanied by an accelerated degradation of the coastal and marine environments, caused by increasing marine pollution, overexploitation of resources, and the growing impacts of climate change including ocean warming, ocean acidification, intensifying extreme weather events, and sea level rise.

In the light of these developments, the term “Blue Economy” was first introduced at the global platform at the Rio+20 conference in 2012, as a sort of an oceanic parallel to the “Green Economy”. The term “Blue Economy” emerged out of the demands of Small Island Developing States (SIDS) and other coastal nations to address the failures of the Green Economy model to adequately capture the unique characteristics and importance of the coastal and marine environments. The term therefore corresponds to a relatively novel concept which promotes the sustainable and equitable use of coastal and marine resources for economic growth and job creation, while preserving the health of the ocean and its biodiversity. Over time, the policy discussions around the Blue Economy have evolved significantly. However, different countries and organisations have contextualised the Blue Economy differently, based on their specific circumstances and priorities. This has contributed to confusion about what the term actually means. This formed the primary motivation to facilitate more deliberate discussions on Blue Economy under the Indian G20 Presidency and the need to develop a common and comprehensive set of principles to characterise the Blue Economy.

Decoding the “Chennai High-Level Principles for a Sustainable and Resilient Blue/Ocean-based Economy”

The High-Level Principles adopted by the G20 represent a crucial first step towards the development of coherent national and regional Blue Economy strategies and policies. After many hours of intense negotiations, the following nine principles were unanimously adopted by the G20:

Principle 1: Prioritise Ocean Health: Address Marine Pollution, Halt and Reverse Biodiversity Loss, and Conserve Coastal and Marine Ecosystems

Principle 2: Acknowledge and Address the Links between Ocean and Climate

Principle 3: Promote Social and Inter-generational Equity and Gender Equality

Principle 4: Promote the use of Marine Spatial Planning (MSP) for an Integrated Approach to the Blue/Ocean-based Economy

Principle 5: Leverage Science, Technology, and Innovation

Principle 6: Recognise, Protect, and Utilise Indigenous and Traditional Knowledge

Principle 7: Establish and Implement Blue/Ocean-based Economy Monitoring and Evaluation Mechanisms

Principle 8: Strengthen International Cooperation to Tackle Shared Maritime Challenges

Principle 9: Enhance Ocean Finance

A brief description of each of the principles is also provided in the final document that was released at the Ministerial Meeting.[3] Arguably, the first three principles define the core aspects of a “Blue Economy”, which include the protection and preservation of the coastal and marine environments, and the promotion of social equity and gender equality. The last six principles highlight the key enablers for a sustainable and resilient Blue Economy. Importantly, the principles also lay stress upon the importance of aligning Blue Economy initiatives with the goals and targets of existing international agreements and frameworks such as the “Convention on Biological Diversity” and its recently adopted “Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework”, the “BBNJ Agreement” under UNCLOS, the UNFCCC and the Paris Agreement, the “2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development”, amongst others. Indeed, pursuing a Blue Economy provides significant opportunities to contribute towards the international goals on climate change, pollution, and sustainable development.

Principle 2 explicitly highlights the need to acknowledge the interlinkages between ocean and climate, and in turn, the Blue Economy. While all sectors of the Blue Economy are directly or indirectly affected by the impacts of climate change, the Blue Economy also provides a framework to mitigate and adapt-to climate change, which is briefly outlined in Principle 2. For instance, ocean-based renewable energy could be utilised to diversify the renewable energy portfolio, particularly in land-scarce countries such as India. The conservation and restoration of coastal and marine ecosystems provide multiple benefits in the context of climate change, particularly since these ecosystems act as natural carbon sinks and also serve as natural barriers against coastal erosion and extreme weather events. Principle 3 highlights the need for Blue Economy approaches to promote social and inter-generational equity and gender equality. This is a core aspect that determines the effectiveness of any Blue Economy strategy, to facilitate effective participation of all stakeholders in the planning and decision-making processes, as also to ensure equal sharing of the benefits.

Along these lines, Principle 4 calls for an integrated approach towards the Blue/Ocean-based Economy by employing Marine Spatial Planning (MSP), which recognises “the full array of interactions within an ecosystem, balances diverse human uses, and takes into account the need for marine protection and conservation”. Importantly, Principles 5 and 6 talk about the need to leverage modern science, technology and innovation, as well as the need to respect and include indigenous and traditional knowledge, cultures, and practices. Blue Economy approaches and initiatives must be informed by the latest science and facilitated by technological and social innovations to generate and implement solutions for contemporary environmental challenges.

Recognising the inherent interconnected nature of the maritime space, Principle 8 calls for enhanced international cooperation at all levels to address the shared challenges of biodiversity loss, climate change, and marine pollution. This Principle highlights the importance of capacity building, knowledge sharing, technology and the sharing of best practices and common projects and investments, amongst the G20 and beyond it. Finally, Principle 9 recognises the significant financing gap facing ocean-related protection and conservation efforts and calls for the strengthening of financial resources, including for developing countries, from diverse sources — national, international, public and private. Importantly, it also emphasises the opportunities to utilise existing finance mechanisms under the UNFCCC, the Paris Agreement, and the CBD, towards ocean-related actions.

Way Forward

As mentioned earlier, different countries have contextualised the Blue Economy differently in their national policies/strategies, which may or may not cover all the fundamental aspects discussed above. Under the Indian G20 Presidency, the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC) and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) jointly produced a technical study entitled, “Accelerating the Transition to a Sustainable and Resilient Blue Economy”,[4] wherein the authors identified and analysed the Blue Economy approaches of the G20 members. It was found that none of the G20 members had developed a targeted, comprehensive Blue Economy Strategy thus far. While some nations are currently in the process of formulating such a strategy, others have in place comprehensive ocean-centric strategic plans that also encompass elements of the Blue Economy. Most coastal and island countries (within G20 and beyond) have sectoral plans/strategies for individual maritime sectors, some of which may include the basic concepts of the Blue Economy.

In this regard, the “Chennai High-Level Principles on Sustainable and Resilient Blue/Ocean-based Economy” document, adopted by the G20, could serve as a starting point to shape future national and regional strategies on Blue Economy and contribute towards the generation of greater coherence amongst those strategies. The principles cover all the core aspects of sustainability, inclusivity, equity, resilience, integrated management, and finance, which together characterise the Blue Economy. Further studies could provide recommendations and technical guidance on how to effectively operationalise these principles and ensure greater harmony between future economic growth and the natural capacities of our ocean and the planet.

About the Authors:

Dr Pushp Bajaj, who is presently working with UNDP India as a National Consultant on Blue Economy and G20, is an Honorary Adjunct Fellow of the National Maritime Foundation. He may be contacted at bajajpushp@gmail.com.

Dr Chime Youdon is a Research Fellow and head of the Blue Economy and Climate Change (BECC) Cluster at the National Maritime Foundation. She is deeply engaged in a set of major studies relating to resilience of climate change and seaport infrastructures. She may be contacted at climatechange1.nmf@gmail.com.

Endnotes:

[1] G20 Environment and Climate Sustainability Working Group – Chennai High Level Principle for a Sustainable and Resilient Blue/ Ocean-based Economy. https://www.g20.org/content/dam/gtwenty/gtwenty_new/document/G20_ECSWG-Chennai_Principles_for_a_BlueOcean-based_Economy.pdf

[2] J B Jouffray, R Blasiak, A V Norstrom, H Osterblom, and M Nystrom, “The Blue Acceleration: The Trajectory of Human Expansion into the Ocean”, One Earth Perspective No 2, 2020.

[3] G20 Environment and Climate Sustainability Working Group – Chennai High Level Principle for a Sustainable and Resilient Blue/ Ocean-based Economy. https://www.g20.org/content/dam/gtwenty/gtwenty_new/document/G20_ECSWG-Chennai_Principles_for_a_BlueOcean-based_Economy.pdf

[4] MoEFCC & UNDP, 2023. Accelerating the Transition to a Sustainable and Resilient Blue Economy. Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, New Delhi, India 91 pp. https://www.g20.org/content/dam/gtwenty/gtwenty_new/document/G20_ECSWG-Technical_Study_on_Accelerating_the_Transition_to_a_Sustainable_and_Resilient_Blue_Economy.pdf

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!