Abstract

As India awakens from its deep maritime slumber and purposefully marches towards regaining its maritime identity as also its rightful place on the head-table of the community of nations, it is imperative that we delve deep into our rich maritime past and imbibe relevant lessons from our glorious maritime history. The contemporary global shipbuilding industry is characterised by rapid innovation and the continuous integration of advanced technologies. While India continuously strives to cement its position as a self-reliant nation with substantive capacities and substantial capabilities in various sectors, it is crucial to revisit and understand the historical significance of its shipbuilding heritage. This article, focused on the “stitched ship project”, aims to explore the rich history of Indian shipbuilding, tracing its roots from ancient times and examining the surviving shipbuilding traditions and techniques of coastal communities in India that are being employed in the ongoing stitched ship project. The “stitched ship project” is a brainchild of Mr Sanjeev Sanyal, member of the Economic Advisory Council to the Prime Minister and has been commissioned as a result of a tripartite agreement between the Ministry of Culture – the funding agency; the Directorate of Naval Architecture (DNA), Naval Headquarters (NHQ) of the Indian Navy – the overseeing agency; and Ms Hodi Innovations, Goa – the boat builder. A team from the National Maritime Foundation (NMF), comprising Commodore Debesh Lahiri (Retd), Senior Fellow; Ms Ayushi Srivastava, Associate Fellow; and Ms Priyasha Dixit, Research Associate, visited Ms Hodi Innovations located at Divar Island, Goa, where the stitched ship is being constructed. This field visit was in furtherance of one of the seven major research themes of the NMF, viz., to significantly contribute in the ongoing national effort to “Enhance Maritime Consciousness (Maritime History, Maritime Heritage, Maritime Culture, etc.)”, and is a subset of a larger study at the NMF entitled, “Reviving Maritimity in India: Ancient Shipbuilding”. The lessons and outcomes from this field visit would also feed directly into the NMF’s efforts to support the Indian Knowledge System (IKS) division of the Ministry of Education and the MAUSAM initiative of the Ministry of Culture.

The field visit was supported by the generous financial support of Ms Larsen and Toubro, and was undertaken to get a first-hand account of the ancient stitched shipbuilding technique by interacting with Mr Prathmesh Dandekar, the boat designer and owner of Ms Hodi Innovations; the shipwright team led by Babu Shankaran; and the stitching team led by Mr Rajeesh. The NMF team also utilised the opportunity to interact with Dr Varad Sabnis, Founder, Samvardhan Heritage Solutions, who has been contracted by NHQ, and M/s Hodi Innovations with the task of documenting the stitched ship construction process. Dr Sabnis is an archaeologist by profession and has been closely involved with marine archaeological surveys in sites on the eastern and western coasts of India. It is planned to follow-up this article with a detailed report highlighting our country’s rich maritime heritage in the construction of stitched ships which, unfortunately, is a dying art today in the face of stiff competition from lighter and more durable construction material such as fibreglass and carbon composites.

Keywords: Stitched Ship, Maritime Consciousness, Maritime Heritage, Maritime Culture, Indian Maritime History, Maritime Legacy, Maritimity, Ancient Shipbuilding

India’s Maritime Legacy

The story of India’s maritime legacy is not just one of technological prowess but one of cultural exchange as well, since ancient Indian vessels carried not merely goods but also ideas and traditions across the Indian Ocean and beyond. People were compelled seaward by their own lifestyles and thus established their livelihood through the seas. Eventually, the vast networks that spread across the Indian Ocean also spurred large-scale human migration, and these people carried with them their traditions and rituals to distant lands.

Today, as India seeks to reconnect with its glorious maritime past, the revival of stitched shipbuilding is emblematic of national pride and seeks to serve as a bridge to the future, intertwining history with modern efforts to preserve and promote this rich heritage. This article attempts to lay bare the fascinating history of stitched ships in India, exploring the intricate techniques that have been passed down through generations. It highlights the ongoing efforts to revive these traditional shipbuilding methods, ensuring that this ancient craftsmanship continues to sail forward into the future.

The cultural significance of stitched sailing ships extends much beyond their functional utility. They forged connections by bridging diverse cultures and facilitating the exchange of knowledge, technology, and traditions. The resurgence of interest in stitched shipbuilding reflects a broader effort to revive and celebrate India’s maritime heritage. This project aims not only to preserve traditional shipbuilding techniques but also to reignite a sense of pride in India’s seafaring history, ensuring that the knowledge and, skills of ancient shipwrights and community of stitchers are not lost to time.

Historical Voyage: The Stitched Ship’s Journey

It is an unfortunate fact that, with the progression of time, Indian shipbuilding faced a gradual decline. The arrival of the Portuguese, followed by other colonial powers, undoubtedly precipitated a decline in India’s dominant position over its surrounding seascape.[1] In addition to the multitude of impacts of the colonial experience, there was the fast and competitive pace of technological growth to be reckoned with, which led to seminal developments in the shipbuilding industry. The very nature of a ship, from the materials used in construction to the design of the vessel, underwent a rapid evolution.[2] In light of these events, the current efforts surrounding the revival of ‘maritimity’ in India are of crucial importance. One such effort is the aforementioned tripartite agreement to construct a stitched ship using ancient Indian knowledge, preserved and disseminated, mostly through oral tradition, by the coastal communities of India.[3]

The history of stitched shipbuilding in India, known as the Tankai method, dates back over 2,000 years.[4] This unique technique involves stitching wooden planks together using cords instead of nails, and unlike other shipbuilding methods, stitched ships possessed hulls with enhanced flexibility, allowing them to navigate the perilous waters of the Indian subcontinent with ease. The durability of these vessels made them ideal for long voyages, facilitating trade routes that connected ancient India with regions as far as Southeast Asia.

The most reliable surviving evidence of Indian origin with respect to shipbuilding in ancient India, is an 11th century Sanskrit text titled ‘Yuktikalpataru’. The authorship of this text is generally credited to King Bhoja of Malwa. Reputed Indian historian and nationalist, Padma Bhushan Radha Kumud Mookerjee, in his book titled ‘Indian Shipping: A History of the Sea-Borne Trade and Maritime Activity of the Indians from the Earliest Times’, provides an extensive commentary on the aforementioned text. Mookerjee highlights certain shipbuilding methods and techniques, as described in the Yuktikalaptaru, which are uncommonly unique and indigenous to India. His lucid explanation about the various features of the stitched ship provides an excellent insight into the ability and sophistication possessed by Indian craftsmen/shipbuilders during ancient times.[5] He points out that these Indian shipwrights, along with their extensive skill in techniques concerning shipbuilding, also had an in-depth knowledge of a variety of materials used to construct wooden ships. As mentioned in the Yuktikalpataru, there were distinct classes of ships based on their load-carrying capacity and sea-worthiness.[6]

An interesting point to be noted is that iron was consciously avoided during the construction of these ships. According to the Yuktikalpataru, the use of iron nails was prohibited in sea-going vessels due to the possible risk of exposing the vessel to magnetic rocks in the ocean. However, another plausible explanation for this avoidance may be attributed to the susceptibility of iron to rust. Therefore, in view of the poor material properties of iron nails, shipbuilders stuck to the technique of fastening or “stitching” the wooden planks together with coil yarn, which was subsequently secured (or, in contemporary terms, made waterproof) by dipping it into fish oil.[7]

Evidence of this technique of constructing stitched or sewn ships survives in certain coastal communities to this day. It is this surviving skill that has been employed in the construction of the stitched ship project in progress at Goa. During the field visit, the descriptions of the various techniques employed by the shipbuilders once laid out in the Yuktikapataru were being employed with uncommon dexterity by the shipwrights on site. They were dictated by the traditions passed on to them by their forefathers, and these traditions were subsequently refined by their own hands-on experience. It was indeed intriguing to observe, that to them, their abilities were a matter of enabling their livelihood and as such these abilities may be perceived as a living tradition.

Masterful Craftsmanship: Building a Stitched Ship

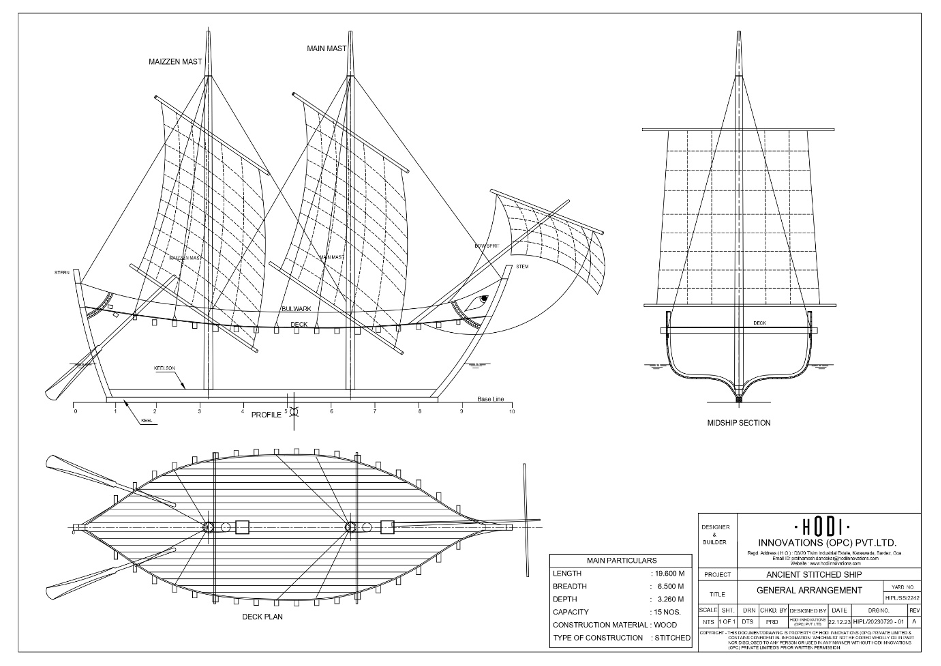

India’s maritime history, stretching back to the Bronze Age, is being revitalised through the Indian government’s initiative to reconstruct a 19.6-metre stitched ship as shown in Figure 1.[8] This project is inspired by a circa 4th century CE vessel depicted in the Ajanta paintings, ancient texts, carvings, and descriptions by foreign travellers.[9] The stitched ship project aims not only to honour but also to revive this ancient craft, showcasing the exceptional skills of India’s remaining traditional shipwrights.

The significance of the stitched ship project extends far beyond its physical construction. It serves as a testament to India’s rich maritime heritage and is intended to rekindle a sense of pride among Indian citizens in their country’s seafaring past. Additionally, by sailing along ancient maritime routes and using traditional navigational techniques, the project seeks to gain insights into historical interactions across the Indian Ocean — interactions that facilitated the exchange of Indian culture, knowledge systems, technologies, and ideas. The project also aims to foster cultural connections with Indian Ocean littoral countries, promoting shared maritime memories. Thorough documentation and cataloguing are key components of this project, ensuring that the knowledge and experiences gained are preserved for future generations.

Figure 1. Concept Design of Stitched Ship

Source: Directorate of Naval Architecture, Indian Navy

While the vessel’s preliminary design had been based on the documentary evidence available, necessary modifications have been made in accordance with modern design parameters to enhance stability and safety. For instance, controlling the vessel’s rolling motion is critical to ensure the vessel’s stability, particularly in the challenging sea states prevalent in the Indian Ocean. ‘Rolling’ refers to the angular rotation of a ship from side to side around a fore-and-aft axis, resembling the motion of a pendulum.[10] If left unchecked, rolling can adversely impact a vessel’s performance. Excessive rolling not only creates physical discomfort for the crew but can also affect the vessel’s navigational accuracy by disrupting the stability required for precise steering. If the ship’s roll exceeds certain limits, it could even compromise the vessel’s structural integrity and, in extreme conditions, lead to capsizing of the vessel. Controlling the roll of a sailing vessel is therefore critical to ensure the vessel maintains a safe angle of ‘heel’, because a vessel that rolls too far risks getting ‘broached’, where it could be struck side-on by waves, increasing its chances of capsizing.

The ship’s design has been suitably modified to comply with the International Maritime Organization (IMO) guidelines on rolling limits of similarly sized vessels. These guidelines necessitate ships to demonstrate their ability to withstand the combined effects of wind abeam and rolling under various loading conditions. This is crucial in maintaining the vessel’s overall stability in varying sea states and wind conditions.[11]

As a design measure to counter excessive rolling, the stitched ship’s beam has been widened and its keel height adjusted, thereby lowering the centre of gravity. These structural changes improve the righting moment — the force acting at a radial distance from the fore-and-aft line that brings the ship back to an upright position after rolling. Additionally, the roll period — defined as the time it takes for the ship to complete one cycle of roll — has been optimised through these modifications. A longer roll period allows for smoother motion, reducing the risk of the vessel being thrown off-balance by abrupt wave movements, while also ensuring that the ship returns to an ‘even keel’ after each roll.

Maintaining a proper angle of heel is extremely important as it directly affects the ship’s hydrodynamic efficiency and safety. If the angle becomes too steep, the ship will lose speed and manoeuvrability, while a significantly reduced angle may cause the vessel to drift, reducing its directional stability. By carefully modifying the vessel’s design to achieve the correct balance, the stitched ship can handle a variety of weather conditions, including rough seas, without compromising its seaworthiness.

The stitched ship will be two-masted, with the masts positioned one-third of the distance from the forward and aft positions of the ship. This mast placement ensures that the forces exerted by the square sails are distributed more evenly across the hull, further improving stability. The ship does not have a conventional rudder-tiller combination and the steering will be done using large trailing oars, while stone anchors with a pulley system are being considered for anchoring the vessel, contributing to both manoeuvrability and the maintenance of a steady course in varying sea states.

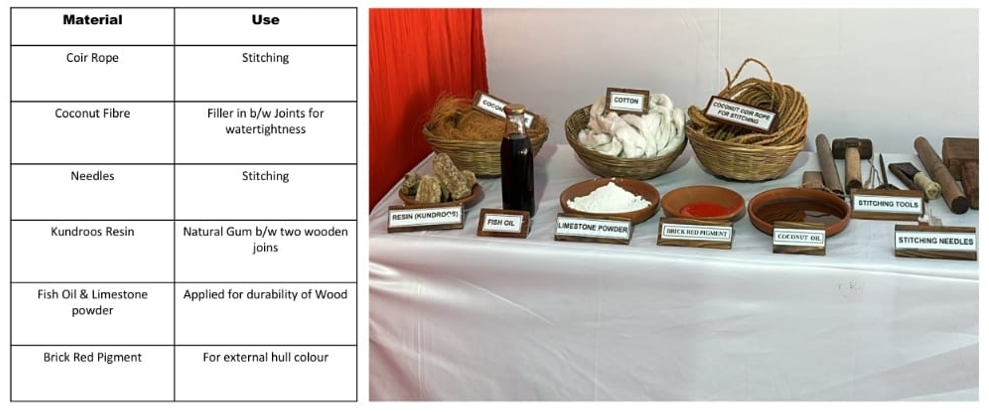

In the process of reviving these ancient shipbuilding techniques, particular attention has been paid to the traditional materials used in constructing the vessel. The natural materials used in construction are shown in Figure 2. Coir rope is utilised for stitching and binding the wooden planks together with remarkable strength. Coconut fibre acts as a filler between the joints of the planks, providing the watertightness crucial for oceanic voyages. The stitching itself is performed with specialised needles, maintaining the authenticity of ancient methods. Kundroos resin, a natural gum, is applied between wooden joints to ensure secure connections, while fish oil and limestone powder are mixed to enhance the wood’s durability. The external hull is treated with a brick red pigment, a traditional technique used for colour and preservation. These natural materials have been carefully selected for their proven effectiveness in withstanding the harsh marine environment, ensuring that the stitched ship will not only embody historical accuracy but also meet modern standards of safety and performance.

Figure 2. Traditional Materials Used for Stitched Ship Construction

Source: Directorate of Naval Architecture, Indian Navy

The stitched shipbuilding process also involves innovative usage of material that harkens back to ancient techniques. The wooden planks are shaped according to the requisite contours of the ship by using a steaming process wherein they are exposed to controlled steam temperature and pressure, in a metal trunking and thereafter shaped using conventional bending methods while the planks are still hot. These planks are then stitched together and sealed as described earlier. A foreseeable scenario, posed by the NMF researchers to the designer, is the strong likelihood of biofouling — the accumulation of marine organisms on the hull — on a slow-moving vessel with the coir stitches presenting an easy-to-adhere underwater hull surface. Our discussions with the designer revealed that to mitigate this, the ship’s hull will be treated with fish oil, a traditional anti-fouling agent. However, the effectiveness of this method in the long term remains to be seen, as the ship’s slow speed and prolonged intervals between voyages may facilitate the rapid growth of marine organisms.[12] Regular periodic monitoring of the underwater hull surface and further research on possible anti-fouling measures in stitched ships will be essential to address this issue.

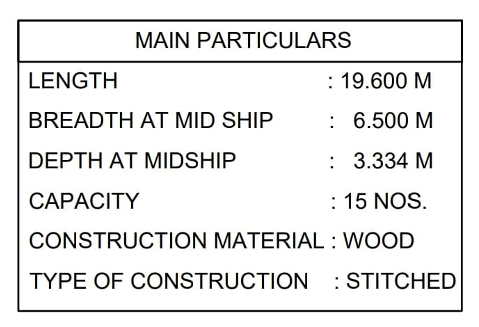

The main particulars of the stitched ship currently under construction in Goa, are enumerated in Figure 3. Additional photographs captured during the site visit of the NMF team are depicted in Figure 4.

Figure 3. Main Particulars of India’s Stitched Ship under construction in Goa

Source: Directorate of Naval Architecture, Indian Navy

Figure 4. Under construction India’s stitched ship in Goa

Source: Captured by authors during field visit

As part of its study, the NMF team interacted with various stakeholders involved in the project, including the Indian Navy and Hodi Innovations, to understand the construction modalities, modern modifications made to the ship, and its sailing plan. According to Commander Hemanth Kumar, Project Officer, NHQ/DNA, the design of the stitched ship adheres to all IMO (Intact Stability) guidelines. The vessel is expected to be launched in early 2025. ‘Launching’ is a formal and often ceremonial custom that celebrates a boat being transferred from land to water for the first time. As such, it is an important naval tradition that is both a public celebration and a way of blessing the ship (and its crew) in an attempt to bring it good fortune on its voyages. The launch will be followed by extensive trials leading up to the vessel’s delivery to the Indian Navy by mid-2025. A trans-oceanic voyage, likely retracing an ancient route from India to Oman, is anticipated by the end of 2025. The authors also learnt that the model testing of the vessel conducted in the towing tank facility at the Department of Ocean Engineering at IIT Chennai had been successful. This testing by the IIT team was meticulously overseen by representatives of the Indian Navy and confirmed that the integration of ancient shipbuilding techniques with modern technology bodes well for the project’s success.

Lessons learnt from similar stitched ship projects, such as the Jewel of Muscat, have been imbibed by the stakeholders and corrective measures incorporated in the construction phases of the stitched ship. The stability and resilience issues experienced by the Jewel of Muscat in extreme weather conditions and high sea states during her voyage, which were resolved by placing ballast weights, offer invaluable practical lessons that have been applied to the current project. For example, during a severe storm, the mast of the Jewel of Muscat snapped, which significantly impacted the ship’s subsequent ability to manoeuvre and maintain course. This incident underscores the importance of robust mast design and material selection, especially for a vessel intended to undertake a long trans-oceanic voyage. The Jewel of Muscat is shown in Figure 5.[13]

Figure 5. Jewel of Muscat

Source: LinkedIn article by Khoula Abdullah

Diverse Shipbuilding Techniques Along India’s Coastline

While the Tankai method of stitching ships is a remarkable testament to ancient ingenuity, it was not the only shipbuilding technique that thrived along India’s extensive coastline. Vessels of simpler designs, constructed from solid wooden planks, bundled reeds and various other means, were other prominent methods. These vessels were known for their durability and stability, making them well-suited for a variety of purposes. For instance, the simple yet effective dugout canoes, carved out from single logs, were commonly used for navigating rivers and coastal waters. Another example can be found in the bundled rafts, which have been documented as far back as the Harappan Civilization. Depictions on seals and amulets from those times represents a curved hull with vertical lines running across it.[14] Another notable method was the construction of Kattu Maram (catamarans), particularly by the Paravas fishing community in Tamil Nadu, which involved tying two logs together to create a stable and flexible watercraft ideal for coastal trade and fishing.[15] These vessels, though modest in design, were adequate for local transportation and fishing, reflecting the resourcefulness of indigenous communities. They also embody a deep and realistic connection to the seas, which remains ingrained in the traditions of coastal communities.

Stitched Ships in the 21st Century

The revival of the ancient art of stitched shipbuilding in India not only preserves a rich cultural heritage but also opens up innovative possibilities for tourism in the 21st century. The reconstruction of a 19.6-metre stitched ship stands as a testament to India’s maritime prowess, offering a unique opportunity to position this project as a flagship initiative for sustainable tourism and at the same time providing tourists with a peek into our rich maritime heritage.

Potential for Tourism

- Heritage Tourism: The stitched ship can offer visitors a firsthand experience of India’s maritime history. Guided tours of the ship, coupled with interactive exhibits, can provide in-depth knowledge about ancient shipbuilding techniques, navigation methods, and the life of seafarers from centuries past. This immersive experience can draw history enthusiasts and those curious about India’s seafaring legacy.

- Adventure Tourism: Sailing experiences aboard the stitched ship can attract adventure enthusiasts. Voyages themed around exploration and discovery can provide a unique, immersive experience, reconnecting participants with nature and the ancient ways of navigation. These experiences would appeal to travellers seeking adrenaline-pumping off-the-beaten-path adventures.

- Cultural Exchanges: By organising international maritime festivals and events centred around the stitched ship, India can showcase its shipbuilding heritage to the world, fostering cultural exchanges with other maritime nations. This can attract tourists interested in experiencing diverse cultures and traditions, further boosting India’s appeal as a travel destination.

- Eco-Tourism: The stitched ship, built using traditional materials and techniques, embodies sustainable practices. Its construction involves no steel or iron-derivatives, fibreglass, etc., relying instead upon eco-friendly materials like coconut fibres, resin, animal fat, fish oil, wood etc. This eco-conscious approach can position the project as an eco-tourism initiative, appealing to travellers who prioritise sustainability.

Challenges and Opportunities

During the interaction of between the NMF team and Mr Prathamesh Dandekar, Managing Director of Hodi Innovations, the latter emphasised that the maintenance of a stitched ship poses significant challenges. The materials and methods used, while sustainable, require meticulous care and regular upkeep to ensure the ship’s longevity and seaworthiness. To assess the financial viability of using a stitched ship for specific tourism ventures, a cost-benefit analysis, comparing it to conventional ships, is essential. This analysis would reveal whether the unique value and eco-friendly appeal of the stitched ship outweighs the higher maintenance costs, thereby establishing a sound economic rationale for its use in tourism.

- Preservation of Traditional Skills: These types of projects help preserve traditional shipbuilding skills, which are nearly extinct in India. Engaging local artisans skilled in the stitched ship technique not only revives ancient craftsmanship but also promotes sustainable tourism practices. Documenting these skills through training programs and apprenticeships can ensure their continuity for future generations.

- Economic Viability: Developing a sustainable business model is crucial for the long-term success of the stitched ship project. Revenue generation through tourism, merchandise, and partnerships with maritime heritage-conscious nations in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) can help generate funding support for the future of the stitched ship project. A thorough cost-benefit analysis will be key to balancing the ship’s cultural value with its economic sustainability.

- Infrastructure Development: To fully realise the tourism potential of the stitched ship, improvement of infrastructure in coastal areas — such as piers, jetties, ports, marinas, and accommodation — will greatly enhance the overall tourist experience. These developments would make it easier for visitors to access the ship and participate in related activities, thereby increasing the stitched ship tourism’s appeal.

- Safety and Regulations: Adhering to modern safety standards and maritime regulations is paramount. Implementing robust safety measures will be essential to building trust among potential tourists, ensuring that the ship not only offers an authentic experience but also a safe one.

Conclusion

The successful voyage and operation of the stitched ship could position it as a major tourist attraction, promoting maritime tourism across India. It aligns with broader initiatives like Project MAUSAM, which aims to reconnect and re-establish cultural links among countries bordering the Indian Ocean. Additionally, the stitched ship project offers significant opportunities for educational outreach. Showcasing India’s rich maritime history to younger generations, it can inspire interest in maritime studies and preserve maritime cultural heritage as part of India’s educational curriculum.

The stitched ship project is not just about reviving an ancient craft; it is about blending tradition with modernity to create a sustainable future. The project holds the potential to significantly contribute to the revival of maritime consciousness in India.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to gratefully acknowledge the efforts of Ms Jaya Lahiri in facilitating communication with Malayali-speaking Mr Babu Shankaran and Mr Rajeesh.

******

About the Authors

Cmde Debesh Lahiri has retired from active service in the Indian Navy and is presently a Senior Fellow of the National Maritime Foundation, New Delhi, and the Executive Editor of its biannual flagship journal “Maritime Affairs”. He is a regular speaker at webinars/seminars/workshops/conferences in India and abroad. He has authored/co-authored book chapters/technical project reports/well-researched articles and was a member of the Expert Advisory Group on Blue Economy to the Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change (MoEF and CC) during India’s presidency of the G20. His areas of research-interest include the maritime geostrategies of Russia, Israel, the UK, the US, and multilateral/regional constructs; Blue Economy and Climate Change; Disaster Resilience; Marine Pollution; Illegal Unreported and Unregulated (IUU) Fishing; Shipbuilding, Ship Repair and Ship Recycling; Multi-disciplinary technical subjects, amongst a host of others. He can be reached at debeshlahiri@gmail.com or mdtc2.nmf@gmail.com

Ayushi Srivastava is an Associate Fellow at the National Maritime Foundation (NMF). She holds a BTech degree from the APJ Abdul Kalam Technical University, UP, and an MTech degree in naval architecture and ocean engineering from the Indian Maritime University (IMU), Visakhapatnam Campus. Her current area of research focus is shipping and shipping-technologies, particularly those aspects that support India’s ongoing endeavour to transition from a ‘brown’ model of economic development to a ‘blue’ one. She can be reached at ps1.nmf@gmail.com

Priyasha Dixit is a Research Associate at the National Maritime Foundation. She completed her graduate studies at the University of Delhi and holds a BA degree in History and Political Science. She also holds an MA degree, majoring in Law, Politics and Society, from Ambedkar University, New Delhi (AUD). Her key areas of research are ‘Enhancing Maritime Consciousness (Maritime History, Maritime Heritage, and Maritime Culture)’, and ‘Maritime Geostrategies of the Indo-Pacific’. She may be contacted at indopac8.nmf@gmail.com

Endnotes:

[1] Priyasha Dixit, “The Case For India’s Seafaring Legacy – Ancient Indian Shipbuilding”, National Maritime Foundation, 12 May 2024, https://maritimeindia.org/the-case-for-indias-seafaring-legacy-ancient-indian-shipbuilding/#_ftnref22

[2] Royal Museums Greenwich, Shipbuilding at Greenwich, https://www.rmg.co.uk/stories/topics/shipbuilding-1800-present

[3] Government of India, Ministry of Defence, Press Information Bureau Delhi, “Curtain Raiser: Keel Laying Ceremony of Stitched Ship Reviving the Ancient Indian Maritime Tradition”, 11 September 2023,

https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1956382

[4] Government of India, Ministry of Culture, Press Information Bureau Delhi, “The Ministry of Culture and the Indian Navy sign an MoU to revive the ancient stitched shipbuilding method (Tankai method)”, 19 July 2023,

https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1940808

[5] Radhakumud Mookerji, “Indian Shipping: A History of The Sea-borne Trade and Maritime Activity Of The Indians From The Earliest Times”, (London: Longmans), Green And Co, 1912, 20-24.

[6] ibid

[7] Snehal Sripurkar, “Sailing through Centuries: A Journey into the History of Indian Shipbuilding”, Enroute: Indian History, 06 July 2023, https://enrouteindianhistory.com/sailing-through-centuries-a-journey-into-the-history-of-indian-shipbuilding/

[8] Navin Berry, “India’s Maritime Glory, A Stitched ship to sail to South East Asia”, Destination India Conversation, 04 October, 2023 https://www.diconversations.com/indias-maritime-glory-a-stitched-ship-to-sail-to-south-east-asia/

[9] Ujjwal Shrotryia and Arush Tandon, “The Ancient Indian Ship-Building Technique That Navy and Government Want To Document Before It Goes Extinct”, Swarajya, 20 September 2023 https://swarajyamag.com/culture/the-ancient-indian-ship-building-technique-that-navy-and-government-want-to-document-before-it-goes-extinct

[10] Tanumoy Sinha, “Different Types of Roll Stabilization Systems Used for Ships”, Marine Insight, 07 October 2019 Different Types Of Roll Stabilization Systems Used For Ships

[11] Code On Intact Stability for All Types of Ships Covered by IMO Instruments, Resolution A.749(18) adopted on 4 November 1993, International Maritime Foundation

See Also: Adoption Of the International Code on Intact Stability, Resolution MSC.267(85), adopted on 4 December 2008, International Maritime Foundation

[12] Ashley Coutts, Richard F Piola, Chad L Hewitt, Sean D Connell and Jonathan P A Gardner, “Effect of vessel voyage speed on survival of biofouling organisms: Implications for translocation of non-indigenous marine species”, Biofouling 26 (2009): 1–13. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/08927010903174599

See Also: Soon Seok Song, Yigit Kemal Demirel, Claire De Marco Muscat-Fenech, Tahsin Tezdogan and Mehmet Atlar, “Fouling effect on the resistance of different ship types”, Ocean Engineering, Volume 216 (2020) https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0029801820307198

[13] Khoula Abdullah, “Reviving the Ancient Glory: The Remarkable Journey of the Jewel of Muscat”, Article posted on LinkedIn

See Also: Starting the build, Jewel of Muscat https://jewelofmuscat.tv/story/starting-the-build/

[14] Sean McGrail, Boats of the World: From the Stone Age to Medieval Times (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 262.

[15] Radhakrishnan T. et al, Traditional Fishing Practices followed by Fisher Folks of Tamil Nadu, Indian Journal of Traditional Knowledge, Vol 8 (4), October 2009, 543-547, https://nopr.niscpr.res.in/bitstream/123456789/6282/1/IJTK%208%284%29%20543-547.pdf

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!