China and Japan are the warp and weft yarns of a geopolitical tapestry woven across millennia. The two countries share a significant, enduring, and long-running history — marked by both vibrant cultural exchange and devastating conflict. In fact, the first recorded tributary missions to China have been traced back to the mid-first century and early second century. Consequently, from very early on, Japan absorbed Chinese influences in writing systems, art, and philosophy, forging a deep cultural bond. Philosophical traditions, including Confucianism and its various tenets, as well as the indirect flow of Buddhism through Korea, knocked on Japan’s eager doors, as the young country set about trying to instil and inculcate its very own traditions and culture. Trade flourished, with Japan often sending tribute to China, thereby acknowledging, and kowtowing to the latter’s cultural and economic power.

Gradually, however, Western powers and their military influence entered the collective consciousness of East Asia. The 19th century was a turning point and Japan embarked upon a process of rapid and comprehensive “modernisation” over a mere two decades (known as the Meiji Restoration which lasted between 1868 and 1889), now considering China to be a stagnant culture. This shift fuelled tensions, culminating in the brutal Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937 that has left a dark stain on their shared past. While post-war efforts in the 1970s brought economic cooperation and diplomatic ties, historical wounds and regional competition remain. Today, these Asian giants stand as economic powerhouses, their intertwined pasts shaping their present and influencing the future of the East Asian region, and by extension, the Indo-Pacific region, too.

It is important to note that the influence of Korea was integral in fostering ties between the two countries, yet this particular paper will focus mainly on Sino-Japanese relations, and why the understanding of “face” in these relations is relevant to India.

Why is “Face” Relevant?

Viewed through the lens of realism, the world order is considered to be in a perpetual state of anarchy, where no State is inherently benevolent in its intentions or actions. Power is the sole currency, resulting in all actions being driven by self-interest, with States either acting out of fear or embracing aggression. Where, then, does “face” fit in the larger picture of power relations between States? Perhaps the first consideration of relevance is the relationship between the terms “prestige” and “power”.

“Prestige, rather than power, is the everyday currency of international relations, much as authority is the central ordering feature of domestic society.”[1] Whereas ‘Power’ refers to the economic, military, and related capacities and capabilities of a State, ‘Prestige’ refers primarily to the “perceptions” of other States with respect to the credibility afforded to a State’s projected capacities and capabilities and the assessment of its ability and willingness to exercise its power to achieve its objectives.[2]

Interestingly, the former President of France, the late Charles de Gaulle, powerfully asserted that “Authority doesn’t work without prestige, or prestige without distance”.[3] He implied that in order for those at the helm to have an effective reign, both these elements ought to coexist. Prestige goes hand-in-hand with authority and power, fading to irrelevance the moment distance is disregarded. (Appropriate) distance acts as a segregator: it sows mystery and generates awe in its wake as it enchants the populace with prestigious authority. If, on the other hand, there was no distance maintained, the populace would eventually come to realise that those wielding power are no different than them — ordinary human beings needing physical and emotional sustenance to survive. This could lead to scorn and disdain. And, if it were the case that too much distance was maintained between the rulers and the ruled, the latter would eventually feel alienated and neglected, prompting rebellious attitudes. Such rebellious attitudes, stirred by disenchantment, could snowball into rebellions of various forms, of which at least one might be supported by those with interests diverging-from or inimical-to the State.

However, while discussing power and prestige in societies as a whole, it is important to recognise and acknowledge cultural differences between ‘Western’ and ‘Eastern’ nations and peoples. Individualist cultures, or “guilt-based cultures”,[4] tend to overlap with much of the Western world; generally, individualism does not place a great deal of emphasis on the group’s perception of the individual, favouring instead the individual’s interests over the group’s interests.[5] On the other hand, collectivist cultures, or “shame-based cultures”,[6] are located in regions of the non-Western world; here, collectivism typically places the utmost significance on the group’s perception of the individual, favouring the group’s interests over the individual’s interests.[7] Thus, in Eastern societies, any ignominy attached to an individual member of a group tends to pervade and shame the group as a whole. In order to avoid such a situation, the group conditions its constituent individuals — pretty much from birth itself — that their behaviour must always be such as to avoid shaming the collective group. This group itself could be a family, a clan, or a wider association comprising several families or clans. Of course, actions by an individual that bring him or her glory also bring glory to the collective, and as a consequence, the collective conditions its individual members to act in such manner as would not merely avoid shame but bring glory. This correlation between the collective and its individual members is what is broadly known as “face”. In sharp contrast the actions of an individual in most Western societies brings accolades or opprobrium (as the case may be) to him or her but not automatically to the collective. This is why it is frequently felt that the concept of “face” is more than merely honour or even respect but has a close correlation with “prestige’ since the latter is a function of collective perception, and that the concept of “face” is a socio-cultural facet that is largely alien to Western societies as also to those who use Western socio-cultural metrics of judgement.

Given that both Japan and China are generally considered to be collectivist, shame-based societies, “face” is a phenomenon evoking the utmost seriousness and gravity in both States. Both countries are known to lay emphasis on the group over the individual. Both cultures share some fundamental values including the privileging of societal harmony, an abiding respect for hierarchy, and a pronounced sense of in-group loyalty. Yet, their conceptions and understandings of collectivism differ as a result of their distinct socio-cultural influences. Thus, in an article critically evaluating Geert Hofstede’s six-dimension model of interpreting cultures, Ryh-song Yeh argues that Hofstede “imposes his “mental programming” on the interpretation of other cultures”[8] concerning the treatment of Japanese and Chinese values in his study. Yeh further asserts that the concept of family in both of these cultures differs as mentioned below:

“Hsu (1983) has indicated that, although there is no fundamental difference in the Chinese and Japanese kinship system, one difference is that “the Chinese kinship system provided for no more extension than the clan (the size of which is always limited because it is founded firmly on the principles of birth and marriage)”. In Japan the existence of iemoto, “the Japanese kinship system provided for affiliation of men into much larger groupings across kinship lines, each founded primarily on the kin-tract principle” and “the kin-tract principle provides for voluntary entry into any grouping” (p. 373).”[9]

Yeh concludes that the Chinese are, in fact, individualistic when viewed from a societal perspective, while the Japanese are more collectivistic in this regard.[10] However, this criticism of Hofstede’s work does not take away from the essence of his research — the group forms an important part of influencing behaviour in both these cultures.

China’s Concept of “Face”

China, according to the scholar Yutang Lin, is ruled by “three sisters”[11] — Face, Fate, and Favour. “Face”, or mien-tzu as it is widely known in China, is not merely a physical or anatomical feature; it is a complex social currency signifying respect, honour, and reputation. It can be “given” through acts of respect, generosity, or achievement, “gained” through “exemplary behavior, superior performance in some role (as in demonstrating one’s competence, trustworthiness, or superior knowledge—particularly when done in modesty), or enhancement of status (as through ostentation or formal promotion to higher office)”,[12] and “lost” through public humiliation, failure, or disrespect. Maintaining “face” is crucial in all social interactions, from business deals to family gatherings. This social phenomenon deeply influences behaviour, shaping communication styles, decision-making, and even conflict resolution. Understanding “face” is essential for navigating Chinese society effectively, fostering harmonious relationships, and avoiding unintentional incidents of offence.

One of the seminal articles on the conception of “face” was authored by Hsien Chin Hu in 1944 — The Chinese Concepts of Face, wherein it was argued that “face” has not one, but two separate entities in Chinese culture — lien and mien-tzu. Lien, according to Hu, is “a social sanction for enforcing moral standards and an internalized sanction”,[13] and the loss of lien brings about a profound sense of shame as well as public ostracization. In many cases, this (perceived) loss of lien has led to people taking their lives, the taint of the loss being too much to bear. Mien-tzu, on the other hand, is “a reputation achieved through getting on in life, through success and ostentation”,[14] and can be gained, gifted, or lost through a variety of means. However, Hu’s interpretation of mien-tzu shows that there are several layers as well as levels to this entity, suggesting that there are degrees of loss of mien-tzu, and it can be regained gradually too. In sharp contrast, lien does not incorporate any provision of reform or redressal, which is why its perceived loss is quite so grave.[15]

In 1976, David Yau-fai Ho conceptualised his own take on the subject matter — On the Concept of Face. In this article, he acknowledges Hu’s distinction between lien and mien-tzu in terms of judging “face” while rejecting Hu’s view that these distinctions are clear-cut in a linguistic sense, arguing instead that these “terms are interchangeable in some contexts”.[16] Moreover, Ho criticises previous writers for their simplistic analysis of the subject, accusing them of treating the loss and gain of “face” as opposite outcomes without enough discernment between lien and mien-tzu.[17] He argues that while mien-tzu can be spoken of as being gained and lost, lien can only be spoken of as being lost. This is because “regardless of one’s station in life, one is expected to behave in accordance with the precepts of the culture”.[18] Moreover, lien is expected to be maintained at all times, considering that “having lien is a prerequisite for achieving dignity”[19], thereby implying that lien is even more basic than dignity.

Further, Ho asserts that “face” is not a “personality variable”, meaning that it is not “an attribute located within the individual”.[20] Instead, it what others have identified and extended to the person in question. However, despite mien-tzu being subject to several interpretations by the collective, it is simultaneously an individual’s “claim”[21] as well. In this regard, Hui-Ching Chang and Richard Holt suggest that individuals “may vary in their attitudes toward their own mien-tzu”,[22] with several linguistic expressions conveying an individual’s sensitivity regarding their mien-tzu. The degree of an individual’s “face-lovingness” impacts his/her trajectory in society; as mien-tzu can be accumulated, it is always possible to move up the social ladder, by any means whatsoever (including unfair means), thereby feeding into the individual’s love for their own face. This can be seen as an individualistic trait in Chinese society, thus differing from the collectivism that has always been associated with the culture. This also stands at odds with what “face” would look like in Japan, as will be discussed in the succeeding paragraphs.

Japan’s Concept of “Face”

Although the term for (social) “face” — mentsu — in Japanese culture has been borrowed from the Chinese counterpart mien-tzu, the phenomenon itself is not quite the same. Japan has historically been a military-ruled feudal society, with strict hierarchies, held together by a profound sense of honour and shame. China, on the other hand, has been governed by civilians since 200 BC.[23] It is crucial to understand the differences in the societal structure as they determine the variations of “face” in both cultures. In Japan, the role of the samurai/warrior’s sense of honour drives behaviour and mannerisms. It is even argued that mentsu was considered secondary to warriors’ “honour” — a samurai would commit seppuku/hara-kiri to maintain honour.[24] Moreover, Kiyoko Sueda implies that mentsu (“little honour”) is merely one aspect “contributing to an individual’s reputation in the community in daily life”,[25] as the “warrior’s honour” (“big honour”) supersedes everything. Mentsu, or “little honour”, only gained prominence with the decline of the warrior class, suggesting that it became prevalent post the Meiji Restoration Era. Against this backdrop, Chun-Chi Lin and Susumu Yamaguchi opine that mentsu can be defined as an individual’s public image that is dependent upon his/her fulfilment of expected social roles.[26]

Given that Japan is a “shame-based society”, it comes as no surprise that there are several terms for “face”, each of which has its own distinct nuance, based on the context. Some such terms are kao, menboku, and taimen, all of which are sometimes used interchangeably along with mentsu. Kao literally translates to “face” and can refer to (1) the physical part of the body; (2) a person’s name, status, or fame; or (3) social face.[27] Of these, “social face” can be further divided into two categories: mentsu and taimen. Mentsu is — quite incorrectly, in the opinion of this author — considered the equivalent of the Chinese mien-tzu, while taimen[28] refers to the “appearance one presents to others”.[29]

Instead, mentsu can be differentiated from three similar social psychological concepts: self-esteem, impression management/self-presentation, and public self-consciousness.[30] According to Lin and Yamaguchi, mentsu is representative of an individual’s social image, while self-esteem represents an individual’s internal self-image; individuals can maintain, save or protect their own mentsu as well as others’ mentsu, while impression management is concerned only with the self; and finally, mentsu is concerned with the fulfilment of social roles as per societal expectations as well as being attentive to how an individual is perceived in public (by the public), while public self-consciousness is limited to an individual’s degree of attentiveness to perception in public.[31]

It is interesting to note that despite being employed in everyday communication and idiomatic expressions, the terms menboku, taimen, mentsu, and kao have not been “employed as effective terms to explain Japanese social behavior”.[32] Seiichi Morisaki and William Gudykunst give the following reasoning…

“We believe there is at least one plausible explanation for the lack of emphasis on face in explaining Japanese communication. Many Japanese who write on Japanese society and communication tend to look for “unique” aspects of Japanese culture. This line of work often is referred to as nihonjinron (literally discussions of the Japanese). Since the origin of the concept of face is Chinese…, writers looking for unique aspects of Japanese culture would not focus on face.”[33]

…and Akio Yabuuchi adds that the “foci of consciousness in their social behavior are different”,[34] with the key concepts for explaining Chinese social behaviour being mien-tzu and guanxi (relation), whereas those for Japanese are haji (shame) and giri (duty/obligation).[35]

Comparing “Face” in China and Japan: Mien-tzu versus Mentsu

As explained above, the drivers for social behaviour and mannerisms in China are different from those in Japan. These differences explain their different societal structures, even though both societies privilege collectivism over individualism. Although Confucianism has, indeed, permeated deeply into Japanese society and culture, not all aspects have been absorbed. This has led to a split in terms of thought processes in China and Japan, impacting the various nuances of “face”.

Based on Yabuuchi’s theory that Chinese social behaviour can be explained by mien-tzu and guanxi, Yeh’s assertion that the Chinese are individualistic from a societal point of view can be better understood. Yeh argues that one of the factors leading to the failure of Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution was the “strong Chinese family orientation”,[36] and this may seem strange at surface value — how does having a strong family orientation imply being individualistic, when the family itself is a group? Yet, Yeh suggests that “Mao strongly condemned the selfish behaviour that places self-interest above that of the group and the excessive devotion to one’s own family”,[37] as Mao’s own ethos was anti-individualistic or pro-collectivistic. This implies that in Chinese society, the family is not really considered part of the “group” and is seen, instead as being an extension of the “individual”, rendering the prioritisation of the family a “selfish” act. In similar fashion, losing or gaining mien-tzu could be viewed as a “family affair” (by extension), since gaining mien-tzu would impact an individual and his/her “inner circle” (guanxi) positively, while losing mien-tzu would hurt the individual and his/her “inner circle”. This could be one of the reasons for the ruling Communist Party of China trying its very best to instil a sense of nationalism in the Chinese populace, in an attempt to revive some of Mao Zedong’s pro-collectivistic ideologies and fuse them with “Xi-Jinping Thought”.

On the other hand, haji and giri are factors that have deeply impacted Japanese social behaviour, [38] implying that the Japanese are more collectivistic than are the Chinese. For one, the conflict between “loyalty” and “filial piety” does not exist in Japan as it does in China, as per Yeh, since the Japanese are known to privilege loyalty to their organisations over their families.[39] This, in turn, implies that the Japanese do not necessarily discriminate on the basis of kinship and blood relations, which could have been one of the reasons why Japan was able to pave the way for modernisation and industrialisation after contact with the West, as the country truly espoused the ethos of collectivism and working towards the betterment of the group (giri). Moreover, this loyalty towards the organisation stemmed from a historical sense of duty/obligation (on) towards the Emperor, parents, and ancestors, as well as one’s work.[40] Should mentsu be lost, a profound sense of shame (haji) would engulf the individual for failing to have fulfilled social expectations. However, the degree of mentsu loss also depends on the status of the “audience”. If mentsu were to be lost in front of a junior/subordinate, the sense of shame would be greater as compared to a loss of mentsu in the presence of a senior/superior or peer.

Moreover, there is a fundamental difference in the terms mien-tzu and mentsu. The Chinese mien-tzu, being a reputation achieved through doing well in life, permits the ascension of the social ladder through ostentation and/or success. There is no apparent morality tied to mien-tzu, given that Hu ascribes the internalised social and moral sanction to lien. This contrasts with the Japanese mentsu, which serves as the public image dependent on the expected fulfilment of social roles. Japan’s mentsu, unlike China’s mien-tzu, appears to have some of the aspects of lien, rendering a much more challenging ascent up the societal hierarchy, especially since there is no concept of “giving mentsu”. Therefore, this comparison throws light on the differences in social mobility in both cultures.

The following table displays the universal or etic component of “face” across various cultures and regions — representing individuals’ public images — and summarises some of the similarities and differences between mien-tzu and mentsu. The culture-specific or emic component of “face” presents a more precise overview of the characteristics, highlighting the main aspects of mien-tzu and lien; mentsu; and negative face. This is not to say that the aspects that are not emphasised are absent in the culturally “unique” concepts of face; the characteristics mentioned are simply the most dominant ones in their respective concepts.

| Components | Characteristics | |

| Etic | Individuals’ public image | |

| Emic | China | Mien-tzu emphasises individuals’ power.

Lien emphasises individuals’ morality |

| Japan | Mentsu emphasises individuals’ fulfilment of their social role or social position | |

| West | Negative face emphasises individuals’ freedom and personal territory | |

|

Table 1: Common and Unique Components of “Face” Source: Adapted from Chun-Chi Lin and Susumu Yamaguchi, “Japanese Folk Concept of Mentsu: An Indigenous Approach from Psychological Perspectives.” 347.[41] |

||

Culture Clash?

Having contributed extensively to the development of Japanese culture, China historically viewed Japan as “an inferior, younger brother”,[42] and the latter paid obeisance and participated in the tributary system over several centuries. During the Qing dynasty however, after the Western powers reached Chinese waters, Japanese subservience appears to have been shattered once and for all. The Japanese saw how the British forced the Chinese court to open their ports and markets and accept trade in opium. Although this led to the two Opium Wars, the Japanese no longer saw the Chinese as being inherently superior. Having paid due respect to the various dynasties of pre-Qing China, the Japanese no longer considered the Chinese to have any “face” worth saving — a perception that was reinforced following the Qing dynasty’s downfall and the advent of the subsequent Chinese Century of Humiliation.

Moreover, the Japanese seem to have adapted to Western influence better, as they were far more open to improving their own political and military systems,[43] given that their sense of collectivism ensured that the group prospered. China, by contrast, was not as adroit, preferring to stick by what felt familiar, leading to further losses of “face” — beginning with Japan’s imperial ambitions and triumphs over Taiwan and some regions of Manchuria through the Treaty of Shimonoseki. Gradually, Japan’s imperialism led to further encroachment into Chinese territory in the early part of the 20th century.

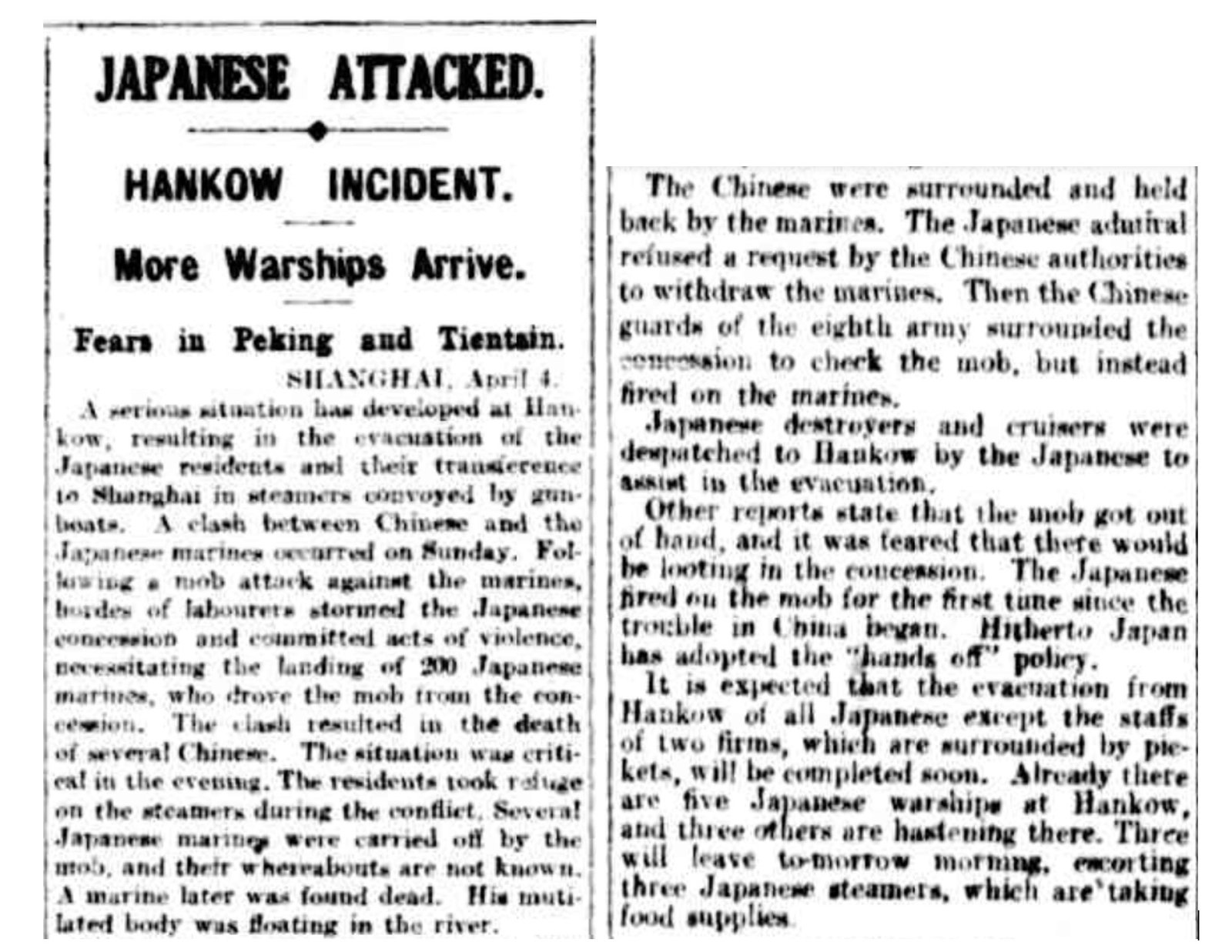

During this period of Japanese occupation in China, one of the first incidents that led to a Japanese “hands-on” policy was the Hankou Incident, which took place on 03 April 1927. Clashes between Japanese marines and the locals led to a mob attack against the Japanese Concession. This resulted in the deployment of 200 Japanese marines to maintain order and safeguard the Concession. This was then followed by Chinese guards firing at the marines instead of the mob, leading to the Japanese marines firing at the uncontrolled mob. Shortly thereafter, the Japanese were evacuated from Hankou. Images 1 and 2 below narrate the details of the incident.

Images 1 and 2: Clippings from The Argus, dated 06 April 1927

Source: Trove Australia[44]

In addition, there was the Nanking Incident in March 1927, which had occurred even prior to the events in Hankou. The Kuomintang (KMT) and its army (the National Revolutionary Army, or the NRA) captured Nanking, following which there were clashes with the foreign forces present there, including the British, Americans, and Japanese.[45] Although reparations were demanded from the National/Cantonese government of South China for the looting and killing of foreigners, these two incidents were perceived in Japan as losses of “face” or mentsu. By losing these “battles” to people whom they deemed inferior, there was a significant sense of collective shame (haji) among the Japanese for not being able to carry out their duty (giri) and this was perceived as a loss of mentsu. On the other hand, these very incidents would have simultaneously led some Chinese to gain mien-tzu, for having successfully exploited a chink in the Japanese armour. Nevertheless, any such gain of mien-tzu was extremely short-lived, however, given the horrific Nanjing Massacre which lasted from December 1937 to January 1938, just prior to the Second World War, wherein tens of thousands of Chinese citizens were raped and slaughtered by soldiers of the Japanese Imperial Army. The city had been the capital of the Nationalist Chinese from 1928 to 1937; it was utterly destroyed and razed to the ground, following which the Japanese made it the capital of their Chinese puppet government.[46] While the Japanese soldiers may have been following their giri, it is unclear whether it affected their mentsu, at least among the Japanese populace. The Chinese, however, would have definitely lost their mien-tzu, having succumbed to the Japanese carnage, while those who survived had to see the city corrupted by being proclaimed the capital of the Chinese puppet government. On the other hand, the Chinese who may have tried to stand their ground, would have died maintaining their lien.

The end of the Second World War saw Imperial Japan utterly defeated, which is when the United States decided to take the overpowered country under her wing, thereby “saving” Japan from the clutches of the communist winds blowing from the northwest. Due to the United States’ interference in Japan’s foreign policy, there were no substantial relations established with Communist China until 1972.[47] For a decade, Japan and China enjoyed friendly relations, with the former offering official development assistance (ODA) to the latter in order “to promote China’s economic development and entry into the international economic order”.[48]

However, relations between the countries soured in the 1980s, owing to a surge in Chinese nationalism and anti-Japanese sentiment, as well as improved relations between China and the Soviet Union. The anti-Japanese sentiment was a result of two key events:

- Japanese high school history textbooks were revised to tone down Japanese aggression against China during WW2, and

- In August 1985, Prime Minister Yasuhiro Nakasone made an official visit to Yasukuni Shrine, where “Class-A” war criminals are entombed.[49]

These moves may have been a deliberate attempt to sabotage a newly emerging China’s mien-tzu facet of “face”. In addition, the dispute over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands in the East China Sea has been roiling both countries for several decades now, particularly since the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) has suggested that the East China Sea houses between one and two trillion cubic feet of natural gas reserves.[50] It is interesting to note that Taiwan had staked a claim to the islands, following which China started making its claim as well. While China claims these islands based on history, Japan claims these islands based on terra nullius (territory belonging to no one).[51] Consequently, Beijing views Japan’s claims as a threat to its sovereignty, both historical and territorial, and by extension, a threat to China’s mien-tzu. On the other hand, Japan’s claims to the islands may well be driven primarily by Tokyo’s aim of enhancing the country’s development as well as the standard of living of the Japanese people, and these disputes could be seen as a roadblock in her giri, which is a threat to Japan’s mentsu.

Why should India Bother?

Despite India not having a sense of “face” similar to that of China’s mien-tzu or Japan’s mentsu, it is crucial for New Delhi to study these East Asian neighbours’ relations, if for no other reason than to ascertain its own standing as well as formulate policy and make decisions favourable to India with regard to the countries in question. A few of the more prominent reasons why India needs to carefully examine the East Asian concept of “face” are:

- Building Strategic Alliances: Studying Sino-Japanese relations would help India understand potential alliances and partnerships that could emerge amidst the shifting regional security landscape (and seascape) within the Indo-Pacific.

- Managing Historical Disputes: Historical tensions between China and Japan offer useful lessons for India in New Delhi’s own dealings with China, highlighting both, the pitfalls to avoid and potentially successful strategies to navigate complex relationships. Moreover, understanding “face” can be a powerful tool in terms of negotiating Indian interests. Likewise, studying Japan through the lens of mentsu would provide India with invaluable lessons on how best to leverage India’s relations with Japan.

- Multilateral Engagement: China and Japan have a history of both cooperation and conflict. Observing their interactions within multilateral organisations can inform and inspire India’s approach to regional diplomacy.

- Analysing India’s Interests: It is in India’s best short-term interest for China to remain preoccupied with the South and East China Seas, as this would buy New Delhi the time that is needed for India to build its capacities and capabilities, especially in terms of her naval and space power. Understanding and internalising the distinction between “face” as applicable to Japan and China would be a hugely useful lever for India.

Conclusion

Ultimately, the relevance of studying how “face” shapes China and Japan’s relations lies in recognising its power as a societal force in the Asian context. It is not merely about cultural etiquette, but about understanding the deep-seated values that influence decision-making, conflict resolution, and social power structures. By grasping the intricate interplay of face within the Sino-Japanese relationship, we gain valuable insights from which to analyse broader geopolitical dynamics. This knowledge also offers insights into potential flashpoints, negotiation tactics, and strategies for building trust — all of which are essential tools for navigating the complexities of diplomacy, business, and multilateral collaborations within the Indo-Pacific region and beyond.

Indian policymakers would be well advised to comprehend and internalise the dynamics of “face” that deeply influence Indian relations with Japan and China. Studying how each of these nations — one a partner and the other an adversary — react when subjected to deep social stimuli provides India with an invaluable lens. While understanding “face” is, of course, crucial for building trust, facilitating constructive dialogue, and fostering mutually beneficial agreements, can it be a “Pavlovian bell” that New Delhi might ring — or withhold from ringing — at will to produce predetermined reactions and responses in Beijing? This tantalising possibility currently engages and informs ongoing research at the National Maritime Foundation.

*****

About the Author:

Ms Krithi Ganesh is a budding social anthropologist and a Research Associate at the National Maritime Foundation, New Delhi. Her research currently focusses upon the drivers of East Asian collective behaviour. She may be reached at pcrt3.nmf@gmail.com.

Endnotes:

[1] Yuen Foong Khong, “Power as Prestige in World Politics”, in International Affairs, University of Chicago, 23 May 2020, https://www.coursehero.com/file/62426586/International-Affairs-Power-as-Prestigepdf/

[2] Robert Gilpin, “War and Change in World Politics”, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 1981, 31

See also: Yuen Foong Khong, “Power as Prestige in World Politics”, in International Affairs, University of Chicago, 23 May 2020, https://www.coursehero.com/file/62426586/International-Affairs-Power-as-Prestigepdf/

[3] “Charles de Gaulle: ‘Authority Doesn’t Work without Prestige, or Prestige without Distance.,’” The Socratic Method, https://www.socratic-method.com/quote-meanings/charles-de-gaulle-authority-doesnt-work-without-prestige-or-prestige-without-distance.

[4] Ruth Benedict, “The Chrysanthemum and the Sword: Patterns of Japanese Culture”, Mariner Books, 2008 (now HarperCollins)

[5] Geert Hofstede, “The 6 Dimensions Model of National Culture by Geert Hofstede,” Geert Hofstede, n.d., https://geerthofstede.com/culture-geert-hofstede-gert-jan-hofstede/6d-model-of-national-culture/

See Also: Krithi Ganesh, “The Chinese Concepts of ‘Face’ by Hsien Chin Hu: A Critique,” National Maritime Foundation, August 17, 2023, https://maritimeindia.org/the-chinese-concepts-of-face-by-hsien-chin-hu-a-critique/

[6] Ruth Benedict, “The Chrysanthemum and the Sword: Patterns of Japanese Culture”.

[7] Geert Hofstede, “The 6 Dimensions Model of National Culture by Geert Hofstede”.

See Also: Krithi Ganesh, “The Chinese Concepts of ‘Face’ by Hsien Chin Hu: A Critique”.

[8]Ryh-song Yeh, “On Hofstede’s Treatment of Chinese and Japanese Values,” Asia Pacific Journal of Management 6, no. 1 (October 1988): 157, https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01732256.

[9] Ryh-song Yeh, “On Hofstede’s Treatment of Chinese and Japanese Values”. 154.

[10] Ryh-song Yeh, “On Hofstede’s Treatment of Chinese and Japanese Values”. 157.

[11] Yutang Lin. “My Country and My People.” The John Day Company (1939).

[12] David Yau-fai Ho, “On the Concept of Face,” American Journal of Sociology 81, no. 4 (January 1976): 867–84, https://doi.org/10.1086/226145.

[13] Hu, “The Chinese concepts of “face”.” 45.

[14] Hu, “The Chinese concepts of “face”.” 45.

[15] Krithi Ganesh, “The Chinese Concepts of ‘Face’ by Hsien Chin Hu: A Critique”.

[16] David Yau-fai Ho, “On the Concept of Face”. 868.

[17] Ibid. 870.

[18] Ibid. 870.

[19] Ibid. 877.

[20] Ibid. 875.

[21] Ibid. 867.

[22] Hui-Ching Chang and G Richard Holt, “A Chinese Perspective on Face as Inter-Relational Concern,” in The Challenge of Facework: Cross-Cultural and Interpersonal Issues, ed. Stella Ting-Toomey (New York: State University of New York Press, Albany, 1994), 95–133.

[23] Tao Lin, “Face Perception in Chinese and Japanese,” Intercultural Communication Studies XXVI, no. 1 (2017): 151–67, https://www-s3-live.kent.edu/s3fs-root/s3fs-public/file/Lin-TAO.pdf.

[24] Kiyoko Sueda, “Differences in the Perception of Face: Chinese Mien-Tzu and Japanese Mentsu,” World Communication 24, no. 1 (1995): 23–31.

[25] Tao Lin, “Face Perception in Chinese and Japanese”. 155.

See Also: Kiyoko Sueda, “Differences in the Perception of Face: Chinese Mien-Tzu and Japanese Mentsu”.

[26] Chun-Chi Lin and Susumu Yamaguchi, “Japanese Folk Concept of Mentsu: An Indigenous Approach from Psychological Perspectives” (Papers from the International Association for Cross-Cultural Psychology Conferences, 2008), https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1134&context=iaccp_papers. 351.

[27] Seiichi Morisaki and William B Gudykunst, “Face in Japan and the United States,” in The Challenge of Facework: Cross-Cultural and Interpersonal Issues, ed. Stella Ting-Toomey (New York: State University of New York Press, Albany, 1994), 47–95. 48.

[28] Most nihonjinron writers looking at social face in Japanese social relations use the taimen version rather than the mentsu alternative.

[29] Seiichi Morisaki and William B Gudykunst, “Face in Japan and the United States.” 48.

[30] Chun-Chi Lin and Susumu Yamaguchi, “Japanese Folk Concept of Mentsu: An Indigenous Approach from Psychological Perspectives.” 348-349.

[31] Chun-Chi Lin and Susumu Yamaguchi, “Japanese Folk Concept of Mentsu: An Indigenous Approach from Psychological Perspectives.” 348.

[32] Akio Yabuuchi, “Face in Chinese, Japanese, and US American Cultures,” Journal of Asian Pacific Communication 14, no. 2 (2004): 261–97. 265.

[33] Seiichi Morisaki and William B Gudykunst, “Face in Japan and the United States.” 48.

[34] Akio Yabuuchi, “Face in Chinese, Japanese, and US American Cultures.” 265.

[35] Akio Yabuuchi, “Face in Chinese, Japanese, and US American Cultures.” 265.

[36] Ryh-song Yeh, “On Hofstede’s Treatment of Chinese and Japanese Values.” 155.

[37] Ryh-song Yeh, “On Hofstede’s Treatment of Chinese and Japanese Values.” 155.

[38] Akio Yabuuchi, “Face in Chinese, Japanese, and US American Cultures.” 265.

[39] Ryh-song Yeh, “On Hofstede’s Treatment of Chinese and Japanese Values.” 154-155.

[40] Ruth Benedict, “The Chrysanthemum and the Sword: Patterns of Japanese Culture”, Mariner Books, 2008 (now HarperCollins)

[41] https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1134&context=iaccp_papers

[42] Alison Kaufman, “The ‘Century of Humiliation’ and China’s National Narratives,” March 10, 2011, https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/3.10.11Kaufman.pdf. 2.

[43] Alison Kaufman, “The ‘Century of Humiliation’ and China’s National Narratives.” 2.

[44] “JAPANESE ATTACKED.,” The Argus, April 6, 1927, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/3847757.

[45] Barnard College, “The Nanking Incident,” The View from Ginling (Barnard College, Columbia University, 2020), https://mct.barnard.edu/the-1927-incident/the-nanking-incident.

[46] Adam Augustyn, “Nanjing Massacre | Summary & Facts,” in Encyclopædia Britannica, October 29, 2018, https://www.britannica.com/event/Nanjing-Massacre.

[47] Jun Tsunekawa, “Introduction: Japan’s Policy toward China,” in The Rise of China: Responses from Southeast Asia and Japan, ed. Jun Tsunekawa (Tokyo: The National Institute for Defense Studies, 2009), 9–21. 10.

[48] Jun Tsunekawa, “Introduction: Japan’s Policy toward China.” 11.

[49] Jun Tsunekawa, “Introduction: Japan’s Policy toward China.” 12.

[50] Teshu Singh, “The East China Sea Dispute: Implications for the Indo-Pacific Region,” Indian Council of World Affairs (Government of India), February 9, 2023, https://www.icwa.in/show_content.php?lang=1&level=3&ls_id=9071&lid=5900.

[51] Teshu Singh, “The East China Sea Dispute: Implications for the Indo-Pacific Region.”

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!