This text serves as a continuation of a prior article, which examined the historical and cultural interplay between India and Greece— two civilisations with a well-documented history of maritime contact and significant intellectual exchange dating back to ancient times. The earlier part explored avenues for leveraging the specific relationship between two societies. By borrowing a technological perspective and cultural lens to serve as the objectives, the current article builds on that background and deepens the inquiry by situating shipbuilding as an evolving theme through which the Indo-Greek connection can be further explored.

The contemporary significance of shipbuilding can be assessed by employing two interrelated dimensions. First, it is a marker of technological advancement that affords current practitioners some benefit through the application of retrodiction, that is, the inference of past capabilities considered under appropriate contexts based on current or documented technological accomplishments. Secondly, shipbuilding serves as a crucial means of preserving maritime heritage. It also aids the interpretation of a society’s maritime past as it bridges it to the present by virtue of being an applicable skill. Consequently, the study of the evolution of shipbuilding since antiquity (or at least the earliest possible evidence) fulfils significant scholarly as well as practical objectives. The two aforementioned dimensions, or objectives, form the conceptual foundation of this article.

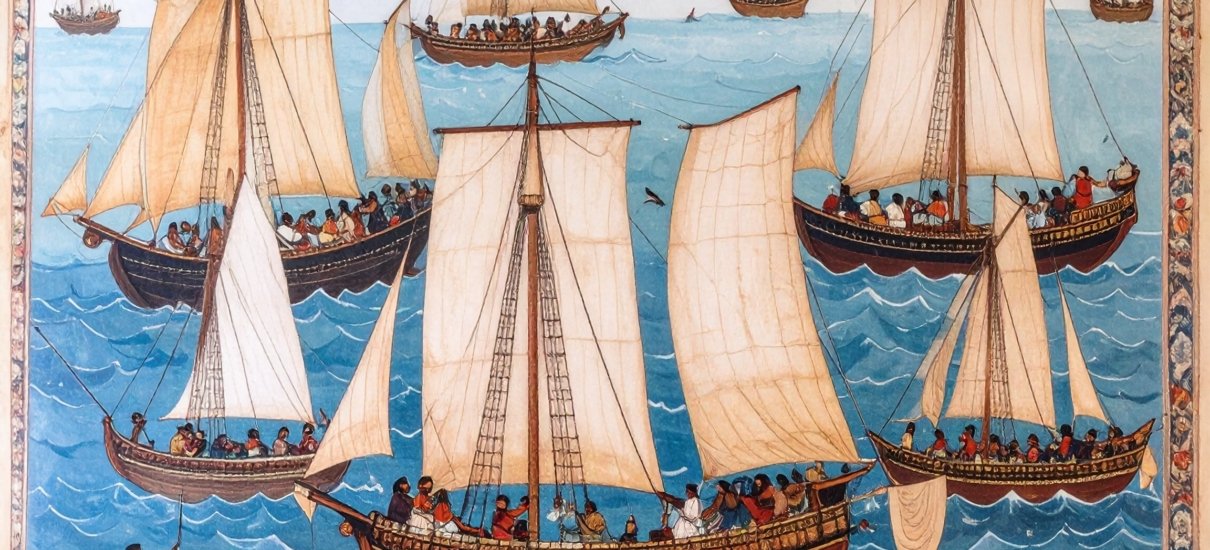

This article undertakes a comparative analysis of the shipbuilding techniques, traditions, and methods of ancient India and ancient Greece, with a particular focus upon materials employed, construction techniques, and the functional diversity of ships within their respective geographical influence. The arguments presented in the analysis function under the presumption that broader socio-political influences in each socio-cultural and socio-economic entity — since neither Greece nor India were full-fledged geopolitical entities as they are in contemporary times — shaped maritime practices in both societies. This piece, therefore, attempts to offer a brief description of the evolution of shipbuilding as a response to regional imperatives and globalising tendencies prevalent in the ancient period. At this stage, it is also essential to acknowledge that the classification of historical periods into broad categories — ancient, medieval, and modern — varies significantly depending on the specific historical trajectory of a given region. Consequently, contextual circumstances are imperative for interpreting the causes behind historical developments — a principle that applies equally to the study of ancient shipbuilding.

Shipbuilding assumes a pivotal role in the general civilisational narrative of the two societies. Along with being a technological enterprise that enabled and refined mercantile expansion and naval warfare, it also functioned as an integral component of cultural exchange, intellectual transmission, transplantation of social norms and structures, and the organisation of the military in varying degrees. The trajectory of the development of this industry in both these ancient societies, however, was strictly dependent upon — and thereby majorly determined by — their distinct geographies, political structures, and strategic cultures. Ancient shipbuilding, therefore, may be viewed as an expression of civilisational ambition and the human need for connectivity.

However, in the broader context of maritime history, the evolution of shipping and shipbuilding cannot be divorced from the gradual understanding and refinement of navigational skills at sea. The story of shipbuilding, therefore, is preceded by the narrative of human societies mastering oceanic navigation, which essentially traces the movement of seamen out into the open sea instead of sailing safely along the coastline. This progression marked an organic yet colossal shift by way of its consequences as seafarers increasingly began to venture beyond their relatively safe zones, which were nearer to the coast, into the uncertain realm of the open sea. Such marked advancements in navigational capabilities — with definitive geographical factors remaining key determinants in the process as well — played a crucial role in shaping the technological evolution of ship construction. As maritime ambitions grew bigger, so too did the functional demands imposed upon seagoing vessels, which in turn prompted continuous innovation in their design, structure, and performance. The demands placed on seafaring vessels began exceeding those of earlier coastal craft, leading to the adoption of more resilient and sturdy designs.

The transition from coastal to open-sea navigation represents a consistent developmental trajectory across all seafaring cultures, with the principal variable in every civilisation being the period in which this shift occurred. Overall, maritime technologies evolved in response to accumulated navigational experience, socio-cultural interactions, and the economic imperatives of trade.

It is presumed that watercraft were initially in the form of dugouts and floating reeds that were bound at the ends, mostly for riverine use. This claim is supported in its essence by Fik Meijer in his work entitled, “A History of Seafaring in the Classical World”, which focuses largely upon the Mediterranean. On the state of seafaring in the classical world, Meijer writes, “…the Mediterranean, the centre of the Classical world, was sailed by Greeks and Romans from the third millennium BC until the sixth century AD”.[1] He adds that while there is little evidence in support of a wholly fleshed-out narrative on “when and how people first ventured to sea in prehistorical times” or the “appearance of the earliest boats”[2], it may be assumed that in the beginning, they were made of hollowed-out wood. Another scholar, Lionel Casson, also remarks that “floats and rafts were preliminaries”[3] in the development of watercraft. In similar vein, McGrail observes that “nowhere in the world have technical discussions of shipbuilding or navigation come down to us from before late medieval times… these shipbuilding and navigational skills were acquired by oral instruction and supervised ‘‘apprenticeships.’’ We cannot, therefore, expect accounts of these techniques to have been compiled before ship design and navigation became science-based and printing became commonplace—that is, until the fifteenth century A.D.”[4]

Meijer elaborates in his work that “in a later phase planks were added to widen and lengthen the dug-out. A subsequent development was the reshaping of the dug-out itself; with the aid of fire and water, the sides were softened and stretched, following which they were reinforced by thwarts and frames. Using the same techniques, the extremities were raised so that they were higher than amidships. The result was an elegant, curved shape similar to that of a plank-built boat” [5]; thus, tracing the gradual transition to plank boats. He subsequently touches upon the trireme — a seagoing vessel — which in the modern imagination, epitomises the peak of technological prowess and sophistication during classical times. Extensively covering its origins and structural specificities, Meijer explores various opinions on this subject in the academic realm. A notable observation that arises from his text is that while the precise origins of the design remain debatable, the refinement of it is widely attributed to the Greeks.

McGrail maintains a more objective analysis as he briefly touches upon the same issues concerning the trireme, but under the theme of “experimental archaeology”. He elaborates upon the ‘Trireme Project’ of the 1980s wherein he observes that there were no remains of a trireme, and it project simply aimed at reconstructing a representative model.[6]

The Athenian Trireme was a quick and manoeuvrable vessel, characterised by a ram. The vessel was propelled by three tiers (or banks) of oars arranged vertically along each side of the hull. Lionel Casson notes that from 600 to 500 BCE, well before the advent of triremes, warships were often depicted in Greek black-figured pottery. Homer, in the Iliad and the Odyssey, mentions ships which were twenty-oared or fifty-oared. According to Casson, by 550 BCE the fifty-oared ship was a design that was accepted as being ideal in battle. These ships were popularly identified as ‘pentekontoros’ (anglicised to ‘penteconters’).[7] These triremes were the successors of this Class of ships.[8] In general, Greek ships were constructed using the ‘shell-first’ technique, which involved the extensive use of mortise-and-tenon joints. Evidence of sewn planking in Greek ships is found much before the period of the triremes, or even the penteconters, dating back to about 800 BCE. McGrail refers to Homer’s passage in the Odyssey for such ships. However, he also states that there exists an alternative hypothesis which claims that Homer’s description may be alluding to both sewn and mortar-and-tenon fastenings.[9]

The Indian example of the aforementioned evolution depends upon a somewhat distinct and comparatively limited body of evidence. One of the earliest depictions of watercraft in the subcontinent is highlighted in a Harappan seal, which portrays a watercraft — presumably designed for riverine navigation — made of reeds that are secured by lashings at the bow and stern.[10] Literary evidence, namely Panini’s “Ashtadhyayi”, provides intriguing insights positioned further back in time. Dated to the 5th Century BCE, this work identifies the various kinds of wood used in the construction of ships in ancient India.[11] In both ancient India and Greece, the selection of construction materials was largely influenced by locally available resources. Indian shipbuilders predominantly utilised teak, favoured for its durability and resistance to marine borers, especially in regions like Gujarat and the Konkan coast.[12] In contrast, Greek shipbuilders employed a variety of timbers — fir, pine, and oak — based on intended use, with pine favoured for speed and oak for durability.[13]

It must, therefore, be noted that these sources of Indian origin, among others, suggest a complex and regionally influenced tradition of shipbuilding that exists simultaneously with (if not actually predating European designs) and operates independently of later classical and European maritime frameworks.

Another treatise dated to the 11th Century CE, namely, the “Yuktikalpataru”, is the work of King Bhoja. It is the sole historical text as of now, in the present body of evidence that elaborates extensively on the subject of shipbuilding relevant to the Indian subcontinent. The Indian shipbuilding technique was characterised primarily by the ‘sewn plank’ method. The sewn-plank technique, evident in ancient maritime traditions across the Indian Ocean, involved binding hull planks together using coir (coconut fibre) ropes. The wood was protected from early decay by coating it with fish oil.[14] However, it is interesting to note that the relatively elaborate nature of the Yuktikalpataru, compared to preceding literary evidence, confirms McGrail’s statement on medieval sources quoted earlier in this text in some respect.[15]

However in the same text, entitled, “Sea Transport: Part I, Ships and Navigation”, Sean McGrail also opines that the techniques or skills involved in shipbuilding in the period ranging from 800 BCE to 500 CE may be perceived as something more akin to an art than a science, as it was largely a process derived from personal experiences, by which is meant that it was extracted from local forms of knowledge that do not abide by modern scientific standards, which would include appropriately recorded and scientifically accurate knowledge and applied skills. Similarly, commenting on the nature of ‘sewn plank’ boats, Casson also states that “the idea of a boat made up of planks sewn together seems strange”[16]. His comments are a result of his modern European sensibilities as can be observed in the immediate remarks made thereafter— “Actually, it is a type that has been in wide use in many parts of the world and in some places still is. In the Indian Ocean, it dominated the waters right up to the fifteenth century, when the arrival of the Portuguese opened the area to European methods”.[17]

The argument that McGrail puts forth, as also the comments that Casson has penned, are rationally introduced and rightfully placed in the context of modern science. However, when this perspective is expanded across both spatial and temporal aspects, this exact notion[18] may prove to trigger a rather challenging foundational fault line in the study of maritime history in certain societies.

Since this article confines itself to the Indo-Greek context, as separate yet simultaneously evolving ancient cultures, it is pertinent to note that both these societies have had a robust maritime tradition since antiquity. A great deal of this knowledge pertaining to the seas, however, is dominated and patronised by marine (or coastal) communities. In both these societies, these communities seem to have existed somewhat at the edge of ancient political structures and thereby lay beyond complete jurisdiction.[19]

The tendency to perceive skills acquired through lived experience as ‘art’, and therefore, not entirely ‘scientific’, creates a gap in the otherwise continuous narrative of the evolution of shipbuilding in such cultures. In other words, it creates a dissonance in the historiography of shipbuilding. This perspective, firstly, indirectly raises the question of whether oral history traditions can be accepted as legitimate or reliable historical sources. Secondly, particularly in the Indian case, the denial to categorise these indigenous methods as scientifically reliable skills leads to their marginalisation within formal scientific discourse. At the same time, given their predominantly practical nature and limited theoretical record (and in certain cases none), this theme also falls through the disciplinary gaps within the social sciences, leaving the study of ancient indigenous shipbuilding balanced precariously along academic borders.

This dilemma leads to an interrogation of the historiographical treatment of ancient shipbuilding within the discipline of history itself. It drives attention towards the critical examination of maritime technologies and local knowledge systems, particularly those originating in non-Western contexts such as that of India, which have been insufficiently or poorly integrated into dominant historical narratives. India’s colonial past has particularly contributed to a systemic undervaluation in global historiography of Indian indigenous knowledge systems and their resulting traditions. Consequently, India’s rich maritime history — despite its indisputable antiquity — has persistently been shadowed by the broader Eurocentric narratives that further obscure its complexity and significance.

In conclusion, the shipbuilding traditions of ancient India and Greece reflect two distinct yet comparably advanced maritime conscious cultures. The socio-political factors that guided the development of shipbuilding industries in the two societies were markedly different. The Greeks laid great emphasis on military efficiency and oared propulsion, which contrasts with the Indian prioritisation of oceanic navigation and mercantile capacity due to the latter’s focus on transoceanic trade. Each tradition, shaped by its own geographical setting, local resources, social background and political structures, nevertheless demonstrated a high degree of indigenous innovation and adaptability. As such, for the purpose of maritime history, both cultures stand as testaments to early human ingenuity in mastering the sea.

Regrettably, cross-cultural exchange in the domain of shipbuilding technology was not mutual. Yet, it was not unidirectional for either society. Greek shipbuilding undoubtedly exerted a profound influence on the Mediterranean basin. Simultaneously, Indian shipbuilding traditions, which still survive in contemporary times, left their imprint across the Indian Ocean littoral. From the dhows on the west coast of India, which reflect an Indo-Arab synthesis in design, to the junks that originated farther east and populated the eastern shores of the subcontinent, Indian interaction across the wider seascape remains irrefutable. While there is no direct evidence of interaction between Greek and Indian shipbuilding techniques, both societies contributed fundamentally to the global development of maritime technologies.

******

About the Author:

Ms Priyasha Dixit is a Research Associate at the National Maritime Foundation. Her area of focus is the enhancement of maritime consciousness in India — a theme that incorporates multiple issues of seminal importance including, inter alia, India’s maritime (seafaring) history (incorporating ancient Indian knowledge systems), the maritime history of the Indian Ocean, India’s maritime heritage and its underwater cultural heritage, as also the MAUSAM initiative of the Government of India. She may be contacted at indopac8nmf@gmail.com.

Endnotes:

[1] Fik Meijer, ‘A History of Seafaring in the Classical World’, Routledge Revivals, Routledge: Taylor & Francis Group, 2014 (originally published in 1986).

[2] Ibid

[3] Lionel Casson, ‘The Birth of the Boat’, Ships and Seafaring in Ancient Times, (University of Texas Press: 1994), p 9.

[4] Sean McGrail, “Sea Transport: Part I, Ships and Navigation”, Chapter 24, The Oxford Handbook of Engineering and Technology in the Classical World, Ed John Peter Oleson, (Oxford University Press: 2008), 606-637.

[5] Fik Meijer, ‘A History of Seafaring in the Classical World’, Routledge Revivals, Routledge: Taylor & Francis Group, 2014 (originally published in 1986).

[6] Sean McGrail, “Sea Transport: Part I, Ships and Navigation”, Chapter 24, The Oxford Handbook of Engineering and Technology in the Classical World, Ed John Peter Oleson, (Oxford University Press: 2008), 606-637.

[7] Lionel Casson, ‘The Birth of the Boat’, Ships and Seafaring in Ancient Times, (University of Texas Press: 1994), p 53.

[8] Ibid

[9] Sean McGrail, “Sea Transport: Part I, Ships and Navigation”, Chapter 24, The Oxford Handbook of Engineering and Technology in the Classical World, Ed John Peter Oleson, (Oxford University Press: 2008), 606-637.

[10] “An Indus Boat Seal”, Blog, Harrapa.com, 17 February 2015, https://www.harappa.com/blog/indus-boat-seal

[11] Sila Tripati, SR Shukla, S Shashikala, and Areef Sardar, “Role of Teak and other Hardwoods in Shipbuilding as evidenced from Literature and Shipwrecks”, Current Science, Vol. 111, No. 7, October 2016, p 1262-1268.

[12] Ibid

[13] Lionel Casson, Ships and Seafaring in Ancient Times.

[14] Snehal Sripurkar, “Sailing through Centuries: A Journey into the History of Indian Shipbuilding”, Enroute: Indian History, 06 July 2023, https://enrouteindianhistory.com/sailing-through-centuries-a-journey-into-the-history-of-indian-shipbuilding/

[15] Refer footnote 3

[16] Lionel Casson, ‘The Birth of the Boat’, Ships and Seafaring in Ancient Times, (University of Texas Press: 1994), p 11.

[17] Ibid

[18] Whether propagating such a notion was their intention or another instance that simply betrayed the deeply ingrained and strict definitions of “science” in modern times, elaborated upon hereafter, is another matter of debate.

[19] E. Lytle, ‘Fishermen, the Sea, and the Limits of Ancient Greek Regulatory Reach’, Classical Antiquity, Vol. 31, No. 1, April 2012, p 1-55.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!