- The President of the United Arab Emirates, Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan (MBZ), undertook a brief yet highly consequential visit to New Delhi on 19 January 2026. Although the visit lasted barely three hours, it yielded several substantive outcomes, most notably the announcement of a Strategic Defence Partnership Framework Agreement between India and the UAE.[1] This development has attracted particular attention as it marks a qualitative shift in bilateral engagement from economic and commercial cooperation towards institutionalised defence and security collaboration.

- Viewed against the backdrop of rapidly evolving security dynamics in West Asia and the broader Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, the timing and substance of MBZ’s visit assume added significance. The regional order that had emerged under prolonged US security stewardship; characterised by Israel’s gradual integration into Arab political frameworks, expanding economic connectivity, and the conceptualisation of ambitious geoeconomic initiatives such as the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC) and the I2U2; has begun to exhibit signs of strain. Intensifying conflicts, the erosion of Israel-Arab normalisation, and the growing divergence in strategic priorities between Saudi Arabia and the UAE have collectively contributed to a fluid and uncertain regional environment.

- In this context, the formalisation of a strategic defence partnership between India and the UAE represents more than a routine bilateral agreement. It reflects a broader realignment of partnerships in response to shifting threat perceptions, emerging power vacuums, and the recalibration of regional security architectures. For the UAE, deeper defence cooperation with India signals a diversification of strategic options beyond its traditional Western security patrons. For India, the partnership underscores its expanding role as a consequential stakeholder in West Asian security and a reliable partner in maintaining stability across the Indian Ocean – Red Sea continuum.

- This article seeks to examine the prospective and far-reaching implications of MBZ’s visit to New Delhi, with specific reference to the proposed Strategic Defence Partnership Framework Agreement. It argues that the agreement must be understood not merely as a bilateral milestone but as part of a wider geopolitical reconfiguration unfolding across West Asia and North Africa, one shaped by great power competition, Gulf rivalries, and the increasing securitisation of maritime and trade corridors. By situating the agreement within this evolving strategic landscape, the paper aims to assess its potential impact on India’s regional posture, the balance of power in the Gulf, and the future of security cooperation across the Red Sea and western Indian Ocean region.

THE UNITED STATES AND THE POST-COLD WAR SECURITY ORDER IN WEST ASIA

- For several decades, the United States has remained the dominant external security guarantor in West Asia, despite periodic challenges from the erstwhile Soviet Union and later Russia, and more recently from China. This role has been anchored in two principal strategic imperatives. First, the maintenance of the petro-dollar arrangement with Saudi Arabia and the associated security guarantees provided to Gulf monarchies,[2] and second, unwavering political and military support for Israel as the cornerstone of US regional strategy.

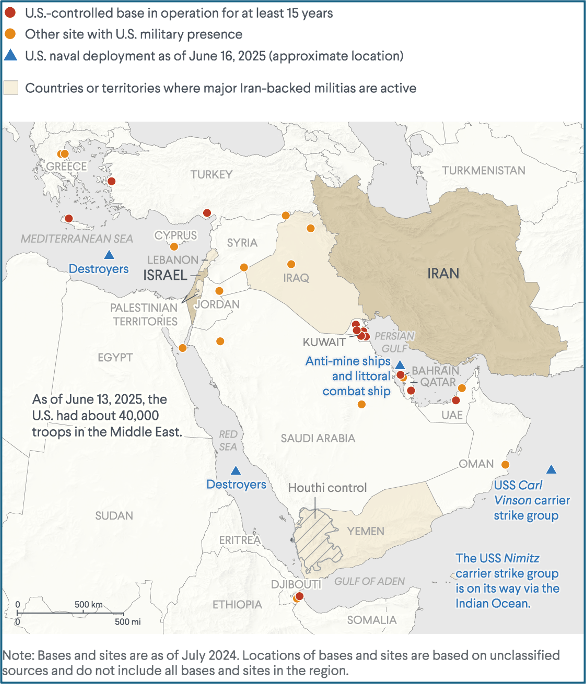

- A third, closely related objective has been the management and containment of Iran. This has included ensuring the uninterrupted availability of the Strait of Hormuz for global energy flows and safeguarding US allies and partners from Iranian coercion. Together, these objectives have enabled the United States to sustain an extensive and practically unrestricted military presence across the region. According to the Council on Foreign Relations, the US operates a broad network of military facilities, both permanent and rotational, across at least nineteen locations in West Asia, with eight permanent bases located in Bahrain, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates.[3] The extent and scale of US presence in the region is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1: US Military Presence in West Asia[4]

Figure 1: US Military Presence in West Asia[4]

- The US-brokered Abraham Accords of 2020 between Israel and four Arab States (the UAE, Bahrain, Morocco, and Sudan) represented a significant institutionalisation of this security architecture, extending its reach into the wider Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region.[5] These agreements were intended not merely as diplomatic breakthroughs but as instruments for consolidating a US-led regional order premised on Israel’s acceptance, collective security coordination, and economic integration.

- In parallel, Washington sought to advance a rapprochement between Saudi Arabia and Israel, which emerged as a central objective of the Biden administration’s regional diplomacy. In a notable shift in posture, Saudi Arabia signalled a willingness to view Israel as a potential strategic partner, subject to progress on the Palestinian issue.[6] However, this opening remained conditional and fragile, revealing the limits of normalisation when confronted by unresolved territorial and identity conflicts, an assumption later exposed by renewed regional hostilities.

- The relative stabilisation of West Asia following these diplomatic initiatives and the resulting increase in trade, as also the benefits from high-end Israeli technology especially in fields such as defence and water and food security,[7] facilitated the conceptualisation of more ambitious geoeconomic constructs. These included the I2U2 grouping (India, Israel, the United States, and the UAE) announced in 2022,[8] and the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC), unveiled during the G20 Summit hosted by India in September 2023.[9] Both initiatives reflected a broader shift from a purely security-centric architecture to one combining strategic stability with economic connectivity, infrastructure development, and technological cooperation.

- Crucially, these initiatives were underwritten by US political sponsorship and investment support, which provided the necessary credibility and coherence for their multilateral acceptance. Yet, their success rested on an additional and largely unarticulated assumption — the persistence of a strong, cooperative, and aligned relationship between Saudi Arabia and the UAE. The apparent convergence of interests between Riyadh and Abu Dhabi, maintained under the umbrella of US security guarantees, was foundational to sustaining a regional environment conducive to trade, investment, and corridor-based integration.

- This security-to-geoeconomics transition can be understood as the transformation of hegemonic stability into corridor diplomacy — a system in which military guarantees enabled normalisation, normalisation enabled economic cooperation, and economic cooperation underpinned transregional connectivity frameworks. However, this architecture was inherently contingent upon a fragile equilibrium. It presumed sustained Israel-Arab normalisation and enduring Saudi-UAE strategic alignment, both of which have since come under increasing strain.

Subsequent regional developments have demonstrated the vulnerability of this model. Renewed conflict involving Israel, escalating proxy confrontations, and the emergence of competitive ambitions between Saudi Arabia and the UAE have undermined the stability on which IMEC and I2U2 were predicated. The very foundations of these geoeconomic projects; security, trust, and political convergence; have proven reversible rather than permanent.

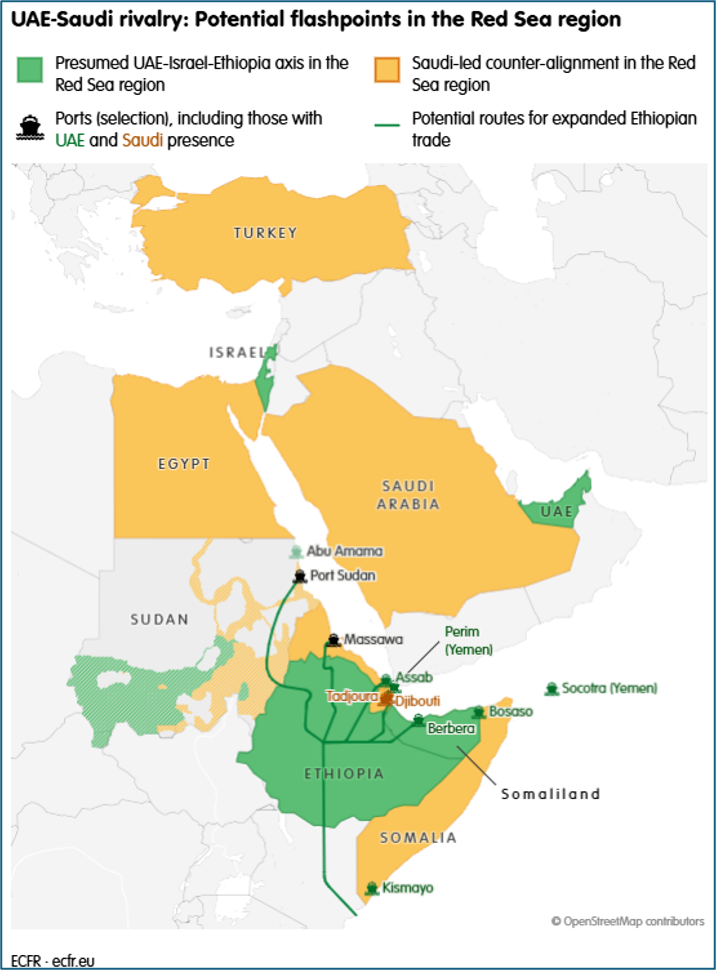

- Thus, while the US-led security order in West Asia succeeded in generating a moment of diplomatic normalisation and economic imagination, it also revealed its structural limitations. The assumption that regional rivalries could be indefinitely subordinated to economic integration underestimated the persistence of regional power competition and unresolved conflicts. The unfolding tensions between Saudi Arabia and the UAE, and their spillover into North Africa and the Red Sea region, now threaten to unravel the geoeconomic architecture that emerged from this brief phase of strategic convergence.[10] Figure 2 brings out the competing spheres of influence of the UAE and Saudi Arabia in the Red Sea-Gulf of Aden region.

Figure 2: UAE–Saudi Rivalry in the Red Sea Region[11]

Figure 2: UAE–Saudi Rivalry in the Red Sea Region[11]

SAUDI-PAKISTAN STRATEGIC MUTUAL DEFENCE AGREEMENT

- On 17 September 2025, Saudi Arabia and Pakistan formalised a Strategic Mutual Defence Agreement (SMDA), a comprehensive security pact that elevates decades of informal military cooperation into a treaty-level commitment between the two states. Under the terms of the agreement, “any aggression against either country shall be considered an aggression against both”, reflecting a collective-defence formulation akin to Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty albeit within a bilateral context.[12]

- The SMDA was signed in Riyadh during Pakistani Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif’s state visit, with Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman presiding over the ceremony. Both governments characterised the pact as an institutionalisation of longstanding security ties, aimed at “enhancing joint deterrence against any aggression” and deepening defence collaboration across multiple military domains.[13] While the pact does not explicitly confer a nuclear guarantee, it bears mention that Saudi Arabia, by aligning with Pakistan, the only Muslim-majority nuclear-armed state, may be signalling an implicit form of extended deterrence.[14]

- Importantly, the agreement codifies into law what had previously been a wide array of informal security arrangements, including decades of Pakistani military deployments, officer training programmes, and advisory cooperation within Saudi Arabia.[15]

Drivers of the Saudi–Pakistan Defence Pact

- The SMDA is best understood through the prism of Saudi Arabia’s current threat perceptions and the evolving regional security environment. While the pact formalises long-standing cooperation, its timing and emphases reflect three immediate strategic drivers. These are:

(a) Reaction to the Israeli Strike on Qatar.

(i) The 09 September 2025 Israeli airstrike on Hamas targets in Doha, despite Qatar’s status as a long-standing US partner, served as a catalyst for heightened insecurity among Gulf states. The attack underscored the possibility that regional conflicts may spill over beyond Lebanon and Gaza and that US security guarantees might prove insufficient or inconsistent in constraining such operations.[16]

(ii) This episode amplified Gulf anxieties regarding the reliability of external security patrons and underscored the need for independent mechanisms that could credibly deter unexpected military actions. The Saudi-Pakistan pact, articulated shortly after the incident, reflected these heightened threat perceptions.[17]

(b) Nuclear Umbrella and Deterrence Dynamics. Pakistan’s status as the only Muslim-majority nuclear-armed state introduces a potentially significant, though ambiguous, dimension to the SMDA. While official statements have been deliberately opaque on whether Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal is extended to Riyadh, the mere association raises strategic expectations of enhanced deterrence against high-end threats.[18] Saudi officials have publicly stated that the agreement “encompasses all military means”, a formulation which, while being non-specific, could be (by design) interpreted as leaving open the possibility of extended deterrence arrangements.[19]

(c) Access to Pakistani Troops for Defence and Regional Operations. Pakistan’s deployment of military personnel in Saudi Arabia is a longstanding feature of bilateral defence relations. Under earlier agreements, Pakistani forces have participated in training, advisory roles, and strategic readiness exercises.[20] The SMDA firmly anchors this relationship in a treaty framework, offering Riyadh assured access to Pakistani troops for deterrence, border defence, and other security tasks as required. This aspect is particularly significant given Saudi concerns across multiple fronts of insecurity — from Iranian regional influence to the ongoing Yemeni conflict and Houthi missile and drone threats to Saudi territory.

Regional Consequences and Security Implications

- Diversification of Saudi Security Partnerships. The agreement illustrates Riyadh’s intent to diversify its security guarantees beyond traditional reliance on the United States. Gulf states have long depended upon US military presence and extended deterrence commitments; however, recent regional contingencies, including the Qatar strike and the protracted Gaza conflict, have prompted re-evaluations of external assurances. This diversification does not necessarily signal a rupture with the US, but it does reflect a pragmatic hedging strategy aimed at reducing overdependence on a single external guarantor.

- Potential Proto-Collective Security Configuration. Although the SMDA remains a bilateral agreement, its structure, especially the mutual defence clause, has prompted analogies to collective defence arrangements such as NATO.[21] Whether the pact could serve as a foundation for modular, coalition-based security frameworks among willing States in the Islamic world, even if it falls short of formal multilateral institutionalisation, remains to be seen.

- Pakistan’s Strategic Gains: Finance, Status, and Deterrence. For Pakistan, the SMDA is not merely a security commitment but also a lever for economic stabilisation and enhanced geopolitical relevance. In effect, it combines “Riyadh’s money” with Pakistan’s large, nuclear-armed military, underscoring the extent to which Saudi financial capacity and Pakistan’s security utility are mutually reinforcing. In practical terms, a formalised strategic defence relationship strengthens Islamabad’s prospects for continued Gulf-linked financial support, an enduring feature of Pakistan’s external financing ecosystem, while simultaneously elevating Pakistan’s standing in the Islamic world by positioning it as a security partner of first resort for the custodian of Islam’s holiest sites.[22] More consequentially, the pact carries implications for Pakistan’s leverage vis-à-vis India, especially in the context of crisis stability and the deterrence environment surrounding cross-border terrorism. The political signalling of a mutual-defence commitment with a leading Gulf power can complicate escalation calculations by introducing uncertainty about the wider diplomatic and strategic costs of coercive action against Pakistan.

Impact on India’s Strategic Calculus

- For India, the Saudi-Pakistan Strategic Mutual Defence Agreement introduces a more complex strategic environment that necessitates careful diplomatic calibration rather than immediate security alarm. On one hand, Pakistan’s enhanced strategic relevance to Saudi Arabia carries potential implications for India’s freedom of manoeuvre during periods of crisis, particularly in scenarios involving terrorist provocation or limited military retaliation. Saudi Arabia’s expectations of restraint from India, driven by its interest in regional stability and protection of its own strategic equities, could impose indirect diplomatic constraints on New Delhi’s response options. Moreover, India’s continued dependence on Gulf energy supplies, of which Saudi Arabia remains a principal partner, adds an additional layer of sensitivity, as energy security considerations inevitably intersect with strategic decision-making in moments of heightened tensions.

- At the same time, these constraints must be viewed in the context of the robust and steadily expanding India-Saudi bilateral relationship. Over the past decade, India and Saudi Arabia have developed a strong partnership encompassing energy cooperation, trade, counter-terrorism coordination, and strategic dialogue.[23] In real operational terms, therefore, the likelihood of Saudi Arabia providing direct military assistance to Pakistan in the event of an India-Pakistan conflict remains low. Riyadh’s overriding interest lies in regional stability and economic transformation under Vision 2030,[24] objectives that would be severely undermined by overt involvement in South Asian hostilities. Consequently, while the SMDA marginally complicates India’s strategic environment by introducing new diplomatic variables, it does not fundamentally alter the military balance. India’s challenge lies less in confronting an emergent Saudi-Pakistan axis and more in managing a nuanced triangular relationship that preserves its energy security, sustains its partnership with Riyadh, and maintains credible deterrence against Pakistan without provoking broader regional entanglements.

TÜRKIYE’S REGIONAL ACTIVISM AND THE “ISLAMIC NATO” NARRATIVE

- Türkiye’s prospective association with the Saudi-Pakistan SMDA has moved from conjecture to a concrete policy track. In mid-January 2026, Reuters reported that Pakistan, Saudi Arabia and Türkiye had prepared a draft defence agreement after nearly a year of talks, indicating an attempt to widen the original Saudi-Pakistan framework into a trilateral arrangement.[25] Ankara’s potential entry introduces a NATO-member State, with advanced defence-industrial capabilities and an established record of security activism across West Asia, North Africa, and South Asia, into the framework.

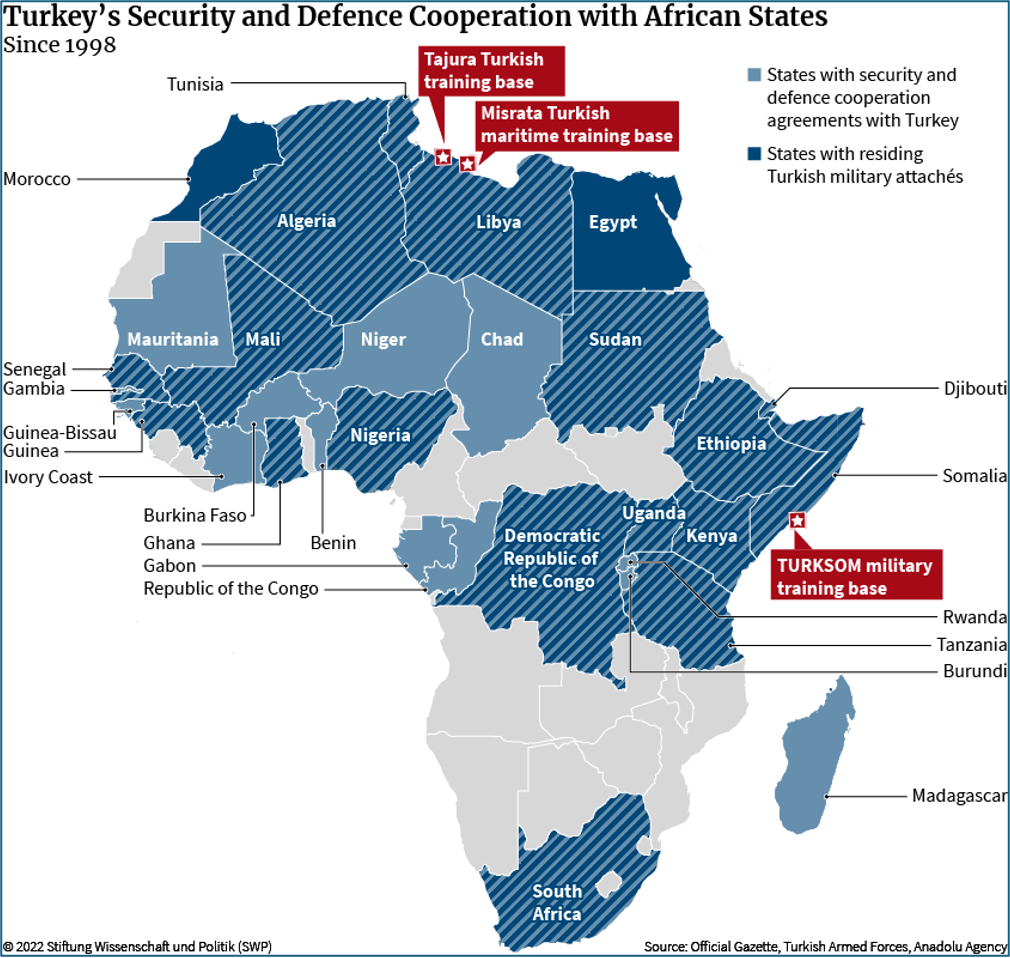

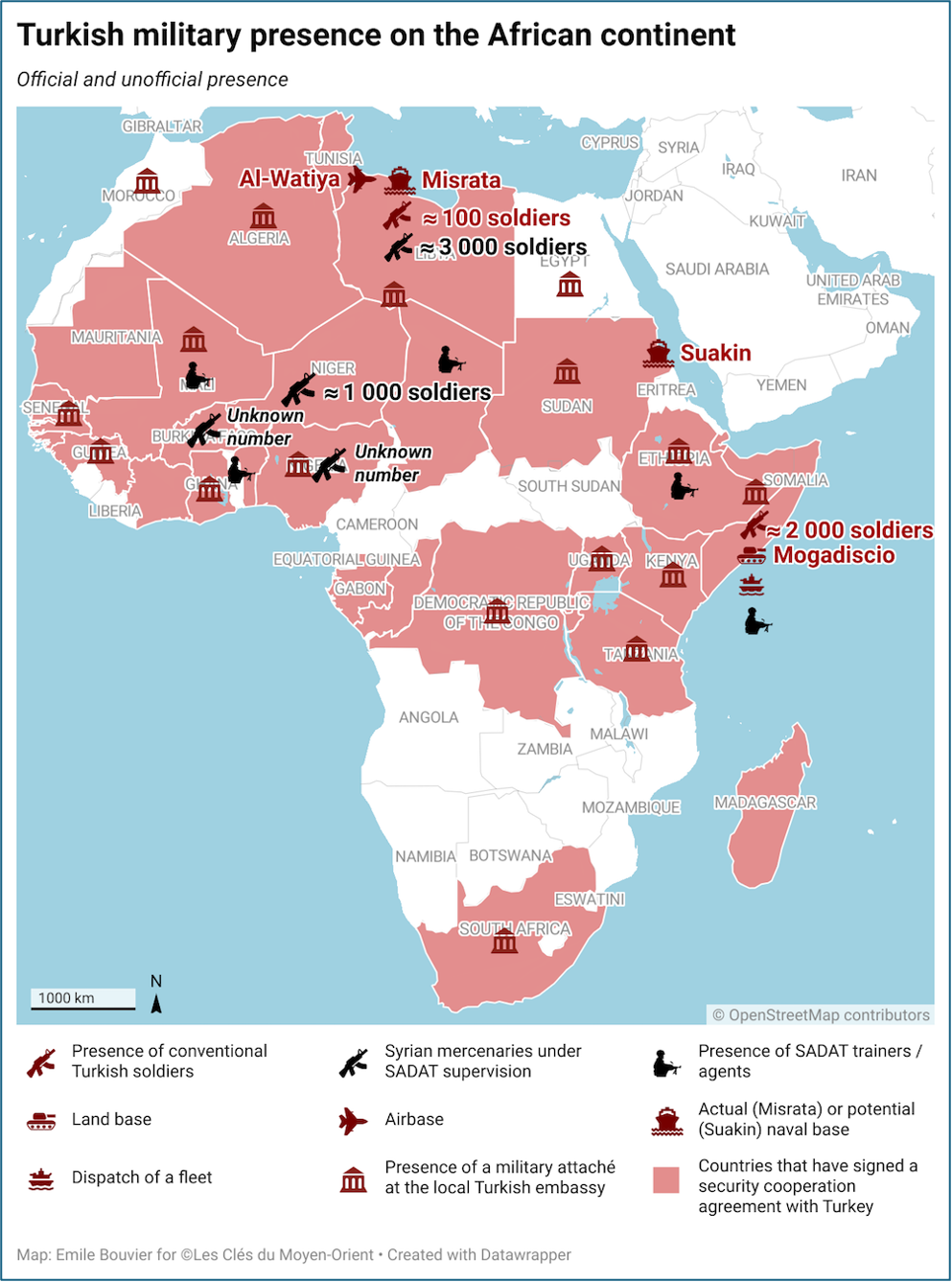

- From an India-centric lens, Türkiye’s disruptive impact is the cumulative effect of specific, observable vectors – (i) Türkiye-Pakistan defence-industrial integration, including platforms and systems that strengthen Pakistan’s ISR/strike and naval modernisation pathways;[26] (ii) Türkiye’s operational and basing presence on India’s extended maritime approaches, most notably in the Horn of Africa (Somalia)[27] and its demonstrated interest in Red Sea access (e.g., Suakin in Sudan)[28] and in North Africa (Libya)[29] (Figures 3 and 4 refer), (iii) Türkiye’s defence-industry outreach to Bangladesh, including high-level engagement explicitly aimed at deepening military cooperation,[30] which is strategically material given Bangladesh’s adjacence to India; (iv) Türkiye’s defence-industrial embedding in Indonesia, a partner India treats as important in the Indo-Pacific maritime context, through a joint venture for the manufacture of Baykar UAVs[31] and the KAAN fighter, as also Milgem frigate procurement;[32] and (v) the broader diffusion of high-technology systems (especially UCAV ecosystems and enabling kill-chain components) across multiple theatres and partners, which lowers the barrier for sophisticated ISR/ strike adoption in India’s wider security periphery.[33]

Figure 3: Türkiye’s Activism in Africa[34]

Figure 4: Türkiye, the New Regional Power in Africa[35]

Figure 4: Türkiye, the New Regional Power in Africa[35]

- This convergence has given rise to the increasingly used descriptor of an “Islamic NATO”,[36] not as a formal institutional alliance with an integrated command structure, but as a shorthand for a potential capability-sharing ecosystem linking Saudi financial resources, Pakistani manpower and nuclear ambiguity, and Turkish defence technology. From an Indian perspective, the concern lies less in the emergence of a cohesive ideological bloc, and more in the cumulative strategic effect of Türkiye’s defence diplomacy, the strengthening of Pakistan’s external support networks, the insertion of a politically adversarial actor into India’s near neighbourhood (Bangladesh), and the complication of India’s maritime partnerships through Türkiye’s industrial embedding in Indonesia’s (as only one example) defence sector.

- The narrative of an “Islamic NATO” reflects the optics of alignment rather than its formal reality. The “Islamic NATO” idea is being overplayed if taken literally but, if understood as a capability-sharing and political signalling ecosystem rather than a formal alliance, one that is not irrelevant for India. All three countries have divergent threat perceptions; competing regional and politico-religious ambitions; different relations with the US, Russia, and China; and no history of sustained trilateral coordination. Türkiye and Saudi Arabia have clashed in Libya and over the Muslim Brotherhood.[37] Pakistan’s primary military focus remains India and internal stability. Saudi Arabia’s overriding priority is Vision 2030 and regional dominance in its immediate vicinity. Further, there is no evidence of any institutional mechanism or structure even close to that of NATO. The term ‘Islamic NATO” thus exaggerates coherence and intent. The impact on India is not alliance-based. As brought out above, it is incremental and indirect.

AN OPENING IN A FRAGMENTING REGIONAL ORDER

- Taken in aggregate, the prospective expansion of the Saudi-Pakistan defence framework with Turkish participation and the accompanying narrative of an “Islamic NATO”, point to the emergence of new, albeit loosely structured, security alignments that intersect with India’s core interests in deterrence, regional stability, maritime security, and crisis management. While these developments do not constitute a formal alliance system directed against India, they nonetheless introduce additional diplomatic and technological variables into India’s strategic environment, particularly through strengthened external support networks for Pakistan and the diffusion of advanced military capabilities in India’s near neighbourhood. In such a setting, India’s response need not be confrontational but must be compensatory, aimed at preserving strategic balance through reinforcing stabilising partnerships, rather than contesting every new alignment.

- The erosion of earlier Gulf strategic cohesion has created both the necessity and the opportunity for the United Arab Emirates to diversify its defence and security partnerships beyond traditional frameworks. For India, this development offers a practical avenue to reinforce its role as a stabilising security partner in West Asia while simultaneously advancing its strategic interests in the immediate neighbourhood. Enhanced defence cooperation with the UAE enables India to account for the implications of Pakistan’s expanding external security linkages and to convey its continuing relevance in regional security calculations to other key actors, including Saudi Arabia and Türkiye. The India-UAE strategic defence partnership thus reflects a deliberate policy choice by both States to adapt to incremental shifts in alignments and perceptions of the balance of power. The partnership can therefore be understood not merely as a bilateral initiative, but as a calibrated response by two like-minded actors to an increasingly fragmented and fluid regional security environment. The next section examines the underlying sources of divergence between Saudi Arabia and the UAE that have made such policy realignments both possible and necessary.

BREAKDOWN OF SAUDI – UAE ALIGNMENT

- The growing divergence between Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates is best understood not as a transient policy disagreement but as a structural rift that has been unfolding over more than a decade.[38] While the two States appeared closely aligned in the aftermath of the Arab uprisings, particularly in their opposition to political Islam, their joint intervention in Yemen, and their shared scepticism towards Iran, this convergence masked deeper differences in strategic priorities, threat perceptions, and regional ambitions.[39] It is increasingly apparent that what once functioned as a strategic partnership has gradually evolved into a relationship characterised by parallel but often competing regional strategies. The erosion of Saudi-UAE cohesion, therefore, reflects accumulated contradictions rather than isolated crises.

- Yemen and the Limits of Policy Convergence. Yemen constituted the earliest and most visible arena in which Saudi-UAE strategic divergence became apparent. While Riyadh pursued the conflict primarily as an effort to restore a unified Yemeni State under an internationally recognised government and to counter Iranian influence through the Houthi movement, Abu Dhabi progressively reoriented its strategy towards southern Yemen, prioritising the suppression of Islamist militias, the cultivation of local proxy forces, and the securing of maritime and port infrastructure along key trade corridors. Over time, the UAE reduced its direct military footprint and increasingly relied on political and material support to the Southern Transitional Council (STC), whose separatist agenda stood in opposition to Saudi Arabia’s objective of preserving Yemeni territorial unity. This divergence revealed a fundamental cleavage in strategic logic: Saudi Arabia remained anchored in territorial restoration and regime stability, whereas the UAE sought influence through networked local partners and control over critical security and commercial nodes in southern Yemen.[40]

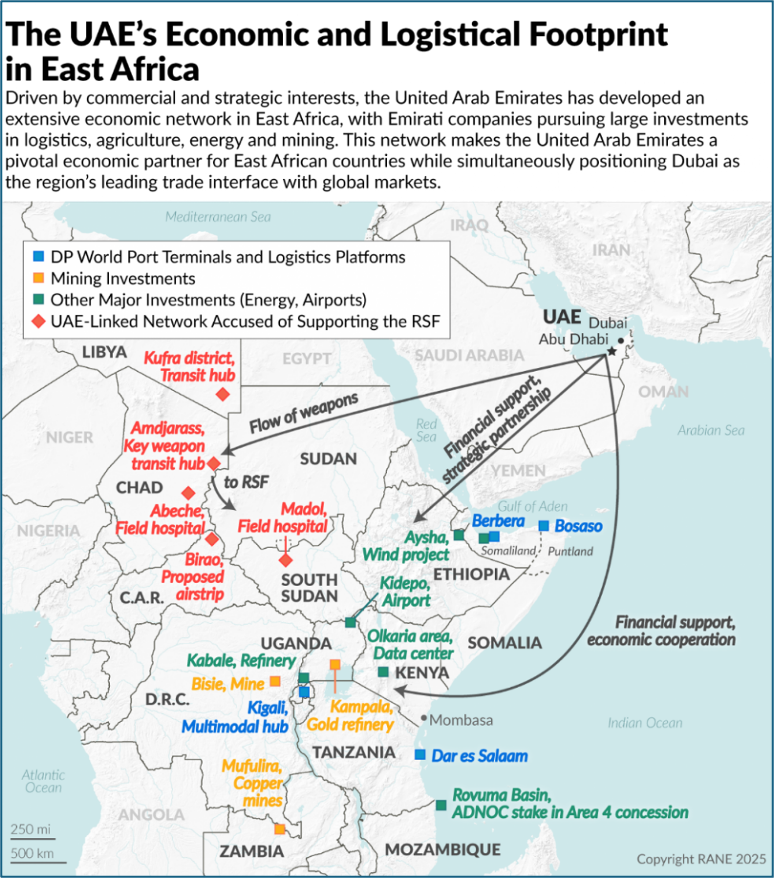

- Divergence in the Red Sea and Horn of Africa. The Red Sea and the Horn of Africa have become arenas of strategic competition in which Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates pursue overlapping but distinct influences that reflect broader divergences in their regional security approaches. Saudi Arabia’s engagement in Sudan and across the western Indian Ocean littoral has been oriented around formal State-to-State diplomacy and the preservation of established governments, while the UAE has leveraged economic investments and relationships with local actors to build influence in port cities and strategic corridors linking Africa to the Arabian Peninsula[41] (Figure 5 refers). This pattern has been visible in the context of Sudan’s civil war, where Gulf actors, including the UAE and Saudi Arabia, have been associated with competing alignments in support of different factions.[42] These developments illustrate how Saudi and Emirati strategies in the Red Sea and Horn are increasingly competitive rather than coordinated, contributing to a fragmented regional security environment.

Figure 5: UAE’s Investments in East Africa[43]

Figure 5: UAE’s Investments in East Africa[43]

- Economic Nationalism and Regional Competition. A second axis of fragmentation lies in economic policy and regional commercial leadership. Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 has driven a deliberate effort to reposition Riyadh as the principal hub for investment, logistics, and multinational headquarters in the Gulf, directly challenging Dubai’s long-standing role as the region’s commercial gateway.[44] Riyadh’s requirement that foreign firms relocate their regional headquarters to Saudi Arabia in order to secure government contracts,[45] and its parallel development of rival logistics and financial centres, has introduced a competitive dynamic with the UAE that extends beyond economics into strategic influence. What began as parallel diversification strategies has increasingly assumed zero-sum characteristics, eroding the political cohesion that once underpinned the Saudi – UAE partnership.[46]

- Contrasting Approaches to Regional Order. Taken together, the preceding patterns of divergence in Yemen, the Red Sea and Horn of Africa, and economic competition suggest that the fragmentation of Saudi-UAE strategic alignment reflects fundamentally different conceptions of regional order and the instruments through which security and influence are exercised. Saudi Arabia appears to remain anchored in a predominantly State-centric framework that prioritises territorial integrity, regime stability, and formal security relationships with recognised governments and major external powers. Its recent efforts at de-escalation with Iran and its reliance on structured security arrangements with partners such as the United States and Pakistan underscore a preference for stabilising the regional balance through sovereign alignments and conventional deterrence frameworks.[47] In contrast, the UAE has adopted a more flexible and networked approach that emphasises influence through control over critical infrastructure nodes such as ports, logistics corridors, and energy assets, and through diversified economic and security partnerships across multiple geographies.

- Consequences for the Gulf Security Architecture. The cumulative effect of these divergences has been the erosion of the assumption that Saudi Arabia and the UAE function as a unified strategic bloc. Instead, the Gulf security environment increasingly reflects a fragmented geometry characterised by overlapping but non-identical alignments. This fragmentation weakens the coherence of earlier US-led security architectures and complicates regional balance-of-power calculations. It is within this context that the UAE’s pursuit of autonomous defence partnerships, including with India, may be understood not as a rupture with Saudi Arabia but as an adaptive response to a less predictable and more competitive regional order.

INDIA’S REGIONAL SECURITY SETTING

- The fragmentation of Saudi-UAE strategic cohesion and the emergence of differentiated regional alignments have altered the structural context of security in West Asia. Instead of operating within a relatively unified Gulf framework, regional and external actors now confront a more plural and competitive security environment shaped by shifting partnerships and evolving threat perceptions. For the UAE, this has created both strategic vulnerability and strategic latitude; vulnerability stemming from the weakening of collective Gulf security assumptions, and latitude in the form of greater scope to pursue autonomous defence and security diversification beyond traditional alignments.

- For India, these shifts acquire sharper strategic salience when viewed against the backdrop of two parallel developments — (i) the deepening of Saudi-Pakistan defence cooperation and (ii) Türkiye’s expanding security footprint across West Asia and the wider Indian Ocean region in conjunction with Islamabad. Together, these trends signal the emergence of security configurations in which Pakistan occupies a more consequential position within Gulf and Islamic security networks, while Türkiye projects influence through defence diplomacy, technology transfers, and political alignment on issues directly affecting India’s security interests. In this context, India’s engagement with the Gulf can no longer remain confined to energy security and commercial ties alone but must respond to a regional order in which new alignments intersect with its immediate neighbourhood concerns. It is within this transformed strategic landscape, marked by the decoupling of Saudi and Emirati regional visions and the growing salience of Pakistan, and Türkiye-linked security arrangements, that the India – UAE Strategic Defence Partnership must be situated and evaluated.

THE INDIA-UAE STRATEGIC DEFENCE PARTNERSHIP: UTILITY AND POLICY PATHWAYS

- The India-UAE Strategic Defence Partnership should be understood as a calibrated instrument of strategic adaptation rather than as a bilateral military alignment. Its primary utility lies in positioning India as a selective security partner within an increasingly fragmented Gulf order while enabling the UAE to diversify its defence relationships without undermining existing commitments. The partnership does not seek to construct a new security bloc; instead, it embeds both states within a networked framework of cooperation that privileges flexibility, interoperability, and strategic autonomy.

- From a policy perspective, the operational focus of the partnership — maritime security, training, defence technology cooperation, and information exchange — addresses concrete vulnerabilities rather than abstract geopolitical objectives. These domains enhance the protection of sea lines of communication, energy infrastructure, and commercial networks, all of which are central to both economies. At the same time, the absence of collective defence clauses or automatic security guarantees preserves diplomatic manoeuvrability for both sides. The partnership thus functions as a risk-mitigation mechanism, strengthening capacity and coordination without generating escalatory commitments.

- Regionally, the partnership produces important signalling effects. It expands India’s role from that of an economic stakeholder to that of a security interlocutor in Gulf defence diplomacy. For Pakistan, this complicates assumptions of exclusive strategic relevance within Arab security frameworks and reduces the leverage derived from its defence relationships with key Gulf States. For Türkiye, whose defence diplomacy and political alignment with Islamabad have gained visibility, the partnership signals that alternative configurations of cooperation will emerge alongside its initiatives. In this sense, the India-UAE partnership does not confront existing alignments directly but introduces balancing options that dilute the consolidation of any single security axis.

- Policy constraints remain substantial and must shape expectations. India’s dependence on Gulf energy supplies and expatriate remittances limits the scope for overtly adversarial posturing, while its commitment to strategic autonomy precludes alliance-like commitments. The UAE must similarly balance its engagement with India against the imperatives of maintaining functional relations with Saudi Arabia and managing ties with major external powers. Further, the continued primacy of the United States as the dominant military actor in West Asia circumscribes the emergence of independent regional security architectures. These factors suggest that the partnership will evolve incrementally, anchored in practical cooperation rather than grand strategic design.

- Over the longer term, the policy significance of the India-UAE Strategic Defence Partnership lies in its contribution to the emergence of networked security arrangements in West Asia. It reflects a shift away from bloc-based security models toward overlapping partnerships that allow States to hedge against uncertainty and fragmentation. For India, this marks a measured transition from economic engagement toward selective participation in regional security management. For the UAE, it reinforces a strategy of autonomy and of hedging through diversified defence relationships. The partnership, therefore, represents a pragmatic response to a plural and competitive regional order rather than a departure from existing security frameworks.

- Policy Pathways. The strategic value of the India-UAE Strategic Defence Partnership will depend less on declaratory commitments than on the manner in which it is operationalised across clearly defined time horizons. Given the fragmented and competitive nature of the regional security environment, a phased approach, linking immediate operational coordination with longer-term capacity-building and institutional integration, offers the most sustainable pathway for deepening cooperation, particularly in the maritime domain.

Short-Term Actions (One–Two Years): Operational Consolidation and Maritime Coordination

- In the short term, policy emphasis should focus on consolidating operational cooperation and institutionalising strategic coordination, with priority accorded to the maritime domain. Regularised combined naval patrols and a higher tempo of advanced bilateral defence exercises, especially naval exercises focused on maritime interdiction, search-and-rescue, and protection of sea lines of communication, would enhance interoperability while remaining non-escalatory in character. These activities should move beyond symbolic engagement towards scenario-based exercises oriented around both conventional and asymmetric maritime threats and infrastructure security.

- To complement operational cooperation, the partnership would benefit from the establishment of an annual high-level security and defence strategy dialogue, supported by quarterly and half-yearly joint assessments at the operational and tactical levels. Such mechanisms would enable both sides to harmonise threat perceptions, review regional developments, and recalibrate cooperation in response to evolving dynamics across the Arabian Sea, Red Sea, and the western Indian Ocean. It is imperative that secure communication linkages be developed for this as also exercises (Indian Navy’s Network for Information Sharing-NISHAR offers an excellent option) and combined operations.

- Institutional embedding of maritime collaboration should also be strengthened through the placement of an International Liaison Officer (ILO) from the UAE within the Information Fusion Centre–Indian Ocean Region (IFC-IOR) framework and also operationalising exchange of “white shipping” information. This would deepen information-sharing on maritime traffic, piracy, trafficking, and suspicious vessel movements, while integrating the UAE more fully into India’s maritime domain awareness architecture.

- An additional priority area lies in critical maritime infrastructure resilience, encompassing the protection of ports, offshore energy installations, subsea cables, and logistics hubs. Joint assessments and action through a dedicated taskforce would align defence cooperation with commercial and energy security priorities, reinforcing the functional character of the partnership.

- Collectively, these short-term measures would establish a durable foundation by linking operational activity, strategic dialogue, and institutional mechanisms.

Medium-Term Actions (Three to Seven Years): Defence-Industrial Integration, Technological Co-development, and Strategic Corridor Activation

- Over the medium term, the India-UAE Strategic Defence Partnership should transition from operational coordination toward structured defence-industrial integration and technological co-development and strategic corridor activation, laying the groundwork for initiatives that can be institutionalised in the longer term. A priority entry point for this phase lies in leveraging existing high-end platforms to anchor deeper institutional cooperation. The presence of the Rafale fighter aircraft in both air forces[48] (together, prospectively the largest operators of the Rafale) offers a practical entry point for collaboration through the establishment of joint maintenance, repair, and overhaul (MRO) facilities in India, coupled with advanced training and simulator programmes. These initiatives would enhance operational readiness, reduce lifecycle costs, and begin embedding durable institutional linkages between the two defence establishments. While this activity would commence in the medium term, it would get institutionalised in the long-term.

- Beyond platforms, the partnership should seek to combine India’s technological talent base and growing defence manufacturing ecosystem with the UAE’s capital resources and investment agility to foster a shared defence innovation environment. This could take the form of a structured framework to support start-ups and mid-sized firms working in areas such as unmanned systems, cyber security, electronic warfare, and maritime surveillance technologies. By aligning India’s engineering and software capacities with Emirati financing and market access, the partnership can move from procurement-driven cooperation toward co-creation of capabilities.

- A more ambitious step would be the creation of a joint sovereign wealth–defence innovation fund dedicated to research and development and the agile acquisition of critical technologies and niche defence firms. Such a fund could be used to invest in dual-use technologies, advanced materials, artificial intelligence, and space-based surveillance, thereby insulating both partners from supply-chain vulnerabilities and external export-control regimes. This approach would also allow the partnership to remain adaptive in a rapidly evolving technological environment rather than being constrained by traditional acquisition cycles.

- At the geoeconomic level, the partnership should be directed toward accelerating the operationalisation of the eastern segment of the IMEC. Israel already constitutes a critical node within the corridor architecture; however, the convergence of India-UAE defence cooperation with the UAE’s normalised security and economic relations with Israel creates an opportunity to translate corridor concepts into coordinated and protected connectivity projects. Defence collaboration can be leveraged to support specific enabling functions such as maritime security for shipping lanes in the Arabian Sea and Red Sea, coordinated protection of port infrastructure and logistics hubs, and joint assessments of risks to corridor operations arising from regional instability or asymmetric threats. In this sense, the India-UAE partnership does not replicate IMEC’s economic logic but complements it by embedding connectivity initiatives within shared mechanisms for infrastructure security, logistics assurance, and regional risk management. The trilateral alignment among India, the UAE, and Israel thus offers a practical mechanism for moving IMEC from declaratory intent toward phased and resilient implementation.

- The recently concluded India-European Union trade agreement[49] provides an additional geoeconomic lever for imparting momentum to IMEC by aligning European commercial interests with corridor stability and connectivity. Enhanced trade volumes and investment flows tied to India-EU market integration create incentives for European stakeholders to prioritise the security of maritime routes, ports, and infrastructure linking the eastern Mediterranean with the Gulf and the Indian Ocean. In strategic terms, greater European material involvement in IMEC-related logistics and industrial nodes strengthens multilateral ownership of corridor outcomes and embeds them within a rules-based commercial framework. This, in turn, introduces a moderating influence on unilateral security postures in the eastern Mediterranean by increasing the political and economic costs of disruption to shared connectivity projects. Rather than directly constraining Turkish ambitions, expanded EU participation in corridor-linked trade and infrastructure promotes a competitive environment in which stability and multilateral coordination become prerequisites for sustained economic returns.

- In parallel, the medium term also presents an opportunity to explore the gradual inclusion of Israel and subsequently select European partners within a defence-industrial ecosystem anchored in India. Such an arrangement would draw upon UAE finance, Israeli and European technology, and Indian manufacturing and human capital, creating a triangular (and later quadrilateral) framework of co-development rather than arms transfer. This would mark a shift from transactional procurement toward collaborative capability creation and prepare the ground for institutionalisation in the long term.

- Taken together, these medium-term initiatives would reposition the India-UAE partnership from a primarily operational relationship to a strategic platform for defence-industrial cooperation and corridor-based connectivity, linking military collaboration with trade, technology, and infrastructure development. By initiating projects that can be consolidated and formalised over time, this phase would serve as the bridge between short-term operational coordination and the longer-term emergence of a networked regional security and economic architecture.

Long-Term Actions (08 – 15 Years): Institutionalisation and Networked Cooperation

- In the long term, initiatives launched during the medium-term phase should be progressively institutionalised into enduring frameworks of defence, industrial, and corridor security cooperation. Platform-specific collaboration, particularly in relation to systems such as the Rafale, should evolve into permanent joint training institutions, integrated MRO and logistics hubs, and standing mechanisms for technological collaboration and doctrinal exchange. What began as project-based cooperation would thus mature into a stable architecture of defence-industrial interdependence anchored in sustained operational interaction and long-term investment.

- A central pillar of this long-term architecture would be the development and protection of energy and industrial corridors linking the Gulf with the Indian Ocean littoral and onward to the eastern Mediterranean. Cooperation should focus on the resilience and security of hydrocarbon supply chains, petrochemical and organic chemical production networks, subsea cables, ports, and logistics hubs that support defence manufacturing and advanced industrial sectors. Joint mechanisms for infrastructure risk assessment, redundancy planning, and crisis response would embed the defence partnership within a broader framework of geoeconomic security rather than military cooperation alone.

- In strategic terms, the India-UAE partnership would function as an anchor for cooperative security practices under conditions of fragmentation and competitive alignment. By linking defence cooperation with corridor security and industrial resilience, both States would contribute incrementally to regional stabilisation while preserving strategic autonomy and avoiding zero-sum rivalries.

- The long-term trajectory of the India-UAE Strategic Defence Partnership would, therefore, rely upon incremental institutionalisation rather than on strategic transformation. Its significance would lie in creating predictable mechanisms for cooperation across defence, infrastructure, and technology domains, enabling both partners to address emerging risks in a fragmented regional environment while preserving strategic autonomy and avoiding rigid or exclusionary security commitments.

Maritime Geometry and Countervailing Alignments

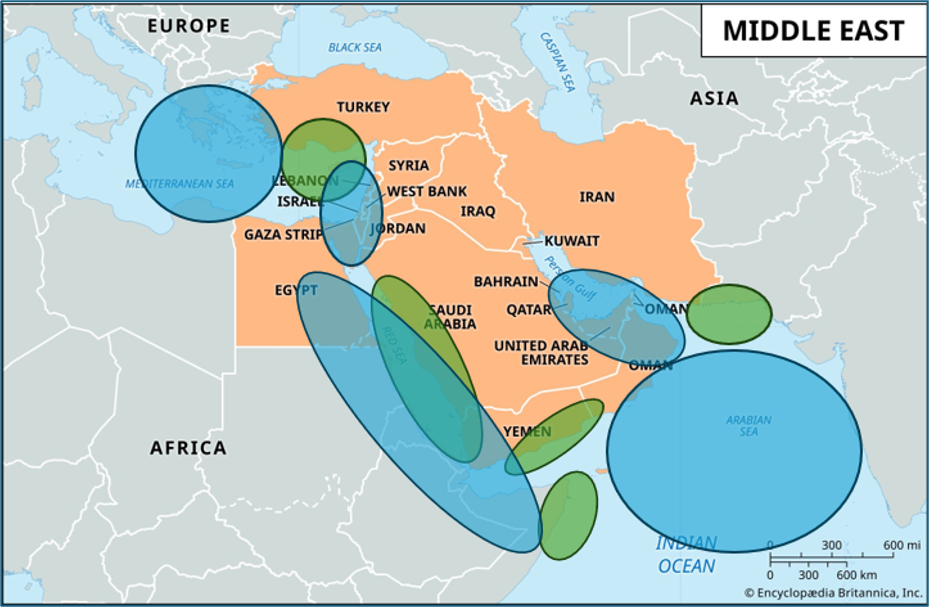

- There is an additional dimension which, while extending beyond the central scope of this paper, merits brief consideration here itself. Beyond institutional and industrial cooperation, the strategic utility of the India-UAE Strategic Defence Partnership can also be examined in spatial terms, particularly across interconnected maritime theatres linking the eastern Mediterranean, the Red Sea-Gulf of Aden corridor, and the western Indian Ocean. The evolving convergence among Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, and Türkiye assumes added significance when viewed through this geographic prism. Collectively, these actors are positioned along sea lanes that carry a substantial proportion of India’s energy imports and commercial traffic and that underpin emerging transregional connectivity initiatives (Figure 6 refers). Even in the absence of a formalised alliance, greater coordination among them introduces new variables into the security environment of critical maritime corridors and chokepoints.

Figure 6: Maritime Influence of the Pakistan-Saudi-Turkish Combine[50]

Figure 6: Maritime Influence of the Pakistan-Saudi-Turkish Combine[50]

- This emerging geometry, however, need not imply strategic imbalance. India’s established maritime posture in the western Indian Ocean, combined with the UAE’s extensive presence across ports and logistics nodes in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden region, constitutes an important countervailing factor. The prospective expansion of Israel’s role along the Red Sea littoral following its recognition of Somaliland,[51] together with its strategic position in the eastern Mediterranean, further extends this configuration. When considered alongside the Trilateral Military Cooperation Plan concluded between Israel, Greece, and Cyprus in December 2025 and India’s deepening strategic engagement with these States (being euphemistically called the “Mediterranean Quad”),[52] these linkages suggest the emergence of a dispersed but mutually reinforcing network of maritime stakeholders with convergent interests in freedom of navigation, infrastructure security, and continuity of transit across critical corridors. This countervailing structure of maritime influence is depicted in Figure 7.

Figure 7: Countervailing Maritime Influence of India, UAE, Israel, Greece, and Cyprus[53]

Figure 7: Countervailing Maritime Influence of India, UAE, Israel, Greece, and Cyprus[53]

- In this context, the India-UAE Strategic Defence Partnership acquires added significance as one element within a broader maritime framework that links defence cooperation with spatial presence and corridor security. Its importance lies not in establishing a counter bloc but in contributing to a pattern of overlapping and issue-based security relationships. This reinforces the paper’s central argument that stability in a fragmented regional order is more likely to be sustained through diversified and networked partnerships than through rigid or exclusionary alignment structures.

INDIA-SAUDI ARABIA RELATIONS: CONTINUITIES AND ADJUSTMENT

- Any assessment of India’s evolving defence and security engagement in West Asia must be situated alongside the enduring significance of India-Saudi Arabia relations. The Kingdome of Saudi Arabia (KSA) remains one of India’s most consequential partners in the region across economic, energy, and human dimensions. The Indian diaspora in the KSA constitutes one of the largest expatriate communities, contributing substantially to remittances and sustaining deep social and labour linkages between the two states. These societal ties continue to provide a stabilising foundation to bilateral relations irrespective of shifts in regional alignments.

- Trade interdependence further anchors the relationship. Saudi Arabia remains among India’s principal sources of crude oil imports, while bilateral trade has expanded to include a growing range of Indian exports in pharmaceuticals, engineering goods, food products, and services.[54] These material linkages generate mutual stakes in stability and continuity rather than confrontation. In this context, the KSA cannot be viewed as a structural adversary of India. The Kingdom’s defence engagement with Pakistan reflects broader geopolitical recalibration and regime security considerations rather than an adversarial posture directed at New Delhi.

- Saudi Arabia’s own economic transformation under “Vision 2030” further reinforces areas of convergence with Indian strategic and economic interests. As a key member and transit hub of the IMEC, the Kingdom occupies a central position in emerging transregional connectivity linking South Asia, the Gulf, and Europe. The IMEC offers Saudi Arabia tangible benefits in terms of logistics integration, industrial diversification, and enhanced access to Indian and European markets. For India, this creates an opportunity to embed its engagement with Riyadh within a cooperative geoeconomic framework that complements its expanding defence partnership with the UAE. Leveraging IMEC as a shared platform for infrastructure development, supply-chain security, and industrial collaboration, would allow India to strengthen strategic trust with Saudi Arabia while reinforcing a triangular dynamic amongst India, the UAE, and Saudi Arabia rooted in connectivity and economic interdependence rather than competing security alignments.

- For India, these structural factors argue for a strategy of engagement rather than counterbalancing vis-à-vis Saudi Arabia. Leveraging diaspora ties, expanding trade, and energy considerations, provides an important foundation for bilateral stability; however, embedding these linkages within shared geoeconomic frameworks such as IMEC offers a more durable basis for strategic convergence. India’s objective need not be to contest Saudi Arabia’s evolving security relationships but to ensure that its own growing role in West Asia is perceived as complementary to regional connectivity and economic integration. Strengthening India-Saudi ties through geoeconomic cooperation, alongside deepening India-UAE defence engagement, thus reflects a broader approach aimed at managing regional fragmentation through diversified and overlapping partnerships rather than through oppositional alignment.

CONCLUSION

- This paper has examined the India-UAE Strategic Defence Partnership within the wider context of shifting security alignments in West Asia, marked by the evolution of Saudi-Pakistan defence cooperation, Türkiye’s expanding strategic activism, and the gradual fragmentation of Saudi-UAE strategic cohesion. Rather than treating these developments as isolated or episodic, the analysis has sought to situate them within a broader transformation of the regional security environment characterised by differentiated threat perceptions, overlapping partnerships, and the erosion of singular security frameworks.

- The central argument advanced is that the India-UAE partnership represents not a departure from India’s traditional engagement with the Gulf but an extension of it into selected security and geoeconomic domains. When viewed alongside India’s enduring ties with Saudi Arabia and the structural opportunities offered by initiatives such as IMEC, the partnership points toward a model of engagement based on diversification, functional cooperation, and strategic autonomy rather than bloc formation or oppositional alignment. In this sense, India’s emerging role in West Asia is best understood as adaptive and incremental, shaped by the need to navigate fragmentation while preserving long-standing economic and political linkages.

- The analysis has also highlighted the importance of maritime geography in shaping the strategic utility of emerging partnerships. Across interconnected theatres linking the eastern Mediterranean, the Red Sea-Gulf of Aden corridor, and the western Indian Ocean, evolving alignments introduce new variables into the security of critical sea lanes and connectivity routes. In this context, the India-UAE Strategic Defence Partnership acquires significance as part of a wider network of overlapping maritime relationships involving Israel and selected European partners. These configurations do not constitute rival blocs but rather, reflect the growing reliance on issue-based and spatially grounded cooperation to preserve access, infrastructure security, and continuity of navigation in an increasingly complex regional environment.

- The policy pathways outlined in this paper deliberately sketch a broad and forward-looking vision of what deeper India-UAE cooperation could, over time, evolve into, spanning maritime collaboration, defence-industrial integration, and corridor-based connectivity. These proposals are necessarily high-level and exploratory. Each would require careful sequencing, institutional design, political consensus, and detailed technical planning before they could be translated into operational policy. Their purpose is not to offer prescriptive blueprints but to provide a strategic framework for thinking about how defence, geoeconomics, and regional stability might be more closely integrated over the long term.

- Ultimately, the significance of the India-UAE Strategic Defence Partnership lies not in its symbolism but in its potential to contribute to a more networked and resilient pattern of regional security cooperation. Whether this potential is realised will depend on sustained political commitment, the ability to manage relations with other key actors, most notably Saudi Arabia and external partners like the US, and the extent to which cooperation can move from declaratory intent to institutionalised practice. The future sketched in this paper may appear ambitious, even grand in conception, but it is precisely such long-horizon thinking that is required if India is to navigate the evolving strategic landscape of West Asia with coherence, balance, and strategic foresight.

- If pursued with consistency and restraint, the trajectory outlined in this paper points toward a larger structural implication. India would not merely deepen bilateral partnerships but could gradually assume the role of a geoeconomic and security connector linking West Asia, Israel, Europe, and the interconnected maritime theatres of the western Indian Ocean, the Red Sea-Gulf of Aden corridor, and the eastern Mediterranean. This outcome remains aspirational and contingent upon a complex interaction of political, strategic, and institutional factors; yet it captures the strategic horizon implicit in the India-UAE Strategic Defence Partnership and the broader vision of networked stability advanced in this study.

********

About the Author:

Captain KS Vikramaditya is a serving officer of the Indian Navy, currently on appointment to the National Maritime Foundation, where he is a Senior Fellow. His research interests are wide and varied and he supplements his formidable academic credentials with his perspectives as an experienced practitioner. His present research focus is on the manner in which India’s own maritime geostrategies are (or are likely to be) impacted by those formulated and executed by external actors operating within the Indo-Pacific. He may be contacted at: indopac10.nmf@gmail.com

Endnotes:

[1] Media Centre, “List of Outcomes: Visit of His Highness Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, President of UAE to India (January 19, 2026)”, MEA, Government of India, 19 January 2026. https://www.mea.gov.in/bilateral-documents.htm?dtl/40602/List_of_Outcomes_Visit_of_His_Highness_Sheikh_Mohamed_bin_Zayed_Al_Nahyan_President_of_UAE_to_India_January_19_2026

[2] Hung Tran, “Is the End of the Petrodollar Near?”, Atlantic Council, 20 June 2024. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/econographics/is-the-end-of-the-petrodollar-near/

[3] Mariel Ferragamo, Diana Roy, Jonathan Masters, and Will Merrow, “U.S. Forces in the Middle East: Mapping the Military Presence”, Council on Foreign Relations, updated 23 June 2025. https://www.cfr.org/articles/us-forces-middle-east-mapping-military-presence/

[4] Mariel Ferragamo, Diana Roy, Jonathan Masters, and Will Merrow, “U.S. Forces in the Middle East: Mapping the Military Presence”, Council on Foreign Relations, updated 23 June 2025. https://www.cfr.org/articles/us-forces-middle-east-mapping-military-presence/

[5] Claudia De Martino, “Assessing the Effects and Prospects of the 2020 Abraham Accords”, Aspenia Online, 18 September 2025. https://aspeniaonline.it/assessing-the-effects-and-prospects-of-the-2020-abraham-accords/

[6] Ali Harb, “US Wants an Israeli-Saudi ‘Normalisation’ Deal. Why Now?”, Al Jazeera, 02 August 2023. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/8/2/us-wants-an-israeli-saudi-normalisation-deal-why-now

[7] Claudia De Martino, “Assessing the effects and prospects of the 2020 Abraham Accords”, Aspenia Online, 18 September 2025. https://aspeniaonline.it/assessing-the-effects-and-prospects-of-the-2020-abraham-accords/

[8] US Department of State, “I2U2”. https://www.state.gov/i2u2

[9] IMEEC International, “India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC)”. https://www.imec.international/

[10] Camille Lons, “Power Struggle: What the Saudi-UAE Rivalry Means for the Red Sea — and Europe”, European Council on Foreign relations, 29 January 2026. https://ecfr.eu/article/power-struggle-what-the-saudi-uae-rivalry-means-for-the-red-sea-and-europe/

[11] Camille Lons, “Power struggle: What the Saudi-UAE rivalry means for the Red Sea — and Europe”, European Council on Foreign relations, 29 January 2026. https://ecfr.eu/article/power-struggle-what-the-saudi-uae-rivalry-means-for-the-red-sea-and-europe/

[12] Maha El Dahan and Saeed Shah, “Saudi Arabia, Nuclear-armed Pakistan Sign Mutual Defence Pact”, Reuters, 18 September 2025. https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/saudi-arabia-nuclear-armed-pakistan-sign-mutual-defence-pact-2025-09-17/

[13] Usaid Siddiqui and Reuters, “Saudi Arabia signs mutual defence pact with nuclear-armed Pakistan”, Al Jazeera, 17 September 2025. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2025/9/17/saudi-arabia-signs-mutual-defence-pact-with-nuclear-armed-pakistan

[14] Saeed Shah and Maha El Dahan, “Saudi Pact puts Pakistan’s Nuclear Umbrella into Middle East Security Picture”, Reuters, 19 September 2025. https://www.reuters.com/business/aerospace-defense/saudi-pact-puts-pakistans-nuclear-umbrella-into-middle-east-security-picture-2025-09-19/

[15] Rabia Akhtar, “Beyond the Hype: Pakistan-Saudi Defense Pact Is Not a Saudi Nuclear Umbrella”, Harvard Kennedy School, Belfer Center, 18 September 2025. https://www.belfercenter.org/research-analysis/beyond-hype-pakistan-saudi-defense-pact-not-saudi-nuclear-umbrella-0

[16] Andrew England, Ahmed Al Omran, and Humza Jilani, “Saudi Arabia Signs ‘Strategic Mutual Defence’ Pact with Pakistan”, Financial Times, 18 September 2025. https://www.ft.com/content/50a48a5a-a022-411d-803e-bbd804f99563

[17] Amnah Mosly, “Saudi-Pakistan Mutual Defense Agreement: What it is, and What it is Not”, Gulf Research Center, September 2025. https://www.grc.net/documents/68dd1614b17b4SaudiPakistanMutualDefenseAgreement2.pdf

[18] Saeed Shah and Maha El Dahan, “Saudi Pact puts Pakistan’s Nuclear Umbrella into Middle East Security Picture”, Reuters, 19 September 2025. https://www.reuters.com/business/aerospace-defense/saudi-pact-puts-pakistans-nuclear-umbrella-into-middle-east-security-picture-2025-09-19/

[19] Rabia Akhtar, “Beyond the Hype: Pakistan-Saudi Defense Pact is not a Saudi Nuclear Umbrella”, Harvard Kennedy School, Belfer Center, 18 September 2025. https://www.belfercenter.org/research-analysis/beyond-hype-pakistan-saudi-defense-pact-not-saudi-nuclear-umbrella-0

[20] Amnah Mosly, “Saudi-Pakistan Mutual Defense Agreement: What it is, and What it is Not”, Gulf Research Center, September 2025. https://www.grc.net/documents/68dd1614b17b4SaudiPakistanMutualDefenseAgreement2.pdf

[21] “Pakistan Calls Saudi Pact Defensive Arrangement, Likens it to NATO”, Times of India, 20 September 2025. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/world/pakistan/pakistan-calls-saudi-pact-defensive-arrangement-likens-it-to-nato/articleshow/124008961.cms

[22] Sushant Sareen, “Pakistan’s Expectations”, ORF Special Report – The Saudi Arabia-Pakistan Defence Agreement: Perspectives from India and the Middle East, edited by Kabir Taneja, November 2025. https://orfme.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/the-saudi-arabia-pakistandefence-agreement.pdf

[23] Harsh V Pant, “The Delhi-Riyadh Axis”, ORF, 05 May 2025. https://www.orfonline.org/research/the-delhi-riyadh-axis

[24] Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, “Vision 2030”. https://www.vision2030.gov.sa/media/rc0b5oy1/saudi_vision203.pdf

[25] Saad Sayeed, Asif Shahzad, and Jonathan Spicer, “Pakistan-Saudi-Turkey Defence Deal in Pipeline, Pakistani Minister Says”, Reuters, 16 January 2026. https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/pakistan-saudi-turkey-defence-deal-pipeline-pakistani-minister-says-2026-01-15/

[26] Aditi Thakur, “The Türkiye–Pakistan Nexus — Strategic Implications for ‘Maritime’ India”, National Maritime Foundation, 14 June 2025. https://maritimeindia.org/the-turkiye-pakistan-nexus-strategic-implications-for-maritime-india/

[27] Al Jazeera, “Turkey sets up largest overseas army base in Somalia”, 01 October 2017. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/10/1/turkey-sets-up-largest-overseas-army-base-in-somalia

[28] Ali Kucukgocmen and Khalid Abdelaziz, “Turkey to Restore Sudanese Red Sea port and Build Naval Dock”, Reuters, 26 December 2017. https://www.reuters.com/article/world/turkey-to-restore-sudanese-red-sea-port-and-build-naval-dock-idUSKBN1EK0Z1/

[29] Reuters, “Jets hit Libya’s al-Watiya Airbase where Turkey may build Base, Sources Say”, 05 July 2020. https://www.reuters.com/article/world/jets-hit-libyas-al-watiya-airbase-where-turkey-may-build-base-sources-say-idUSKBN24608A/

[30] TOI World Desk, “Turkey’s Top Defence Official meets Bangladesh’s Yunus: Military Cooperation Discussed; Second Bilateral Meet in a Year”, Times of India, 08 July 2025. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/world/south-asia/turkeys-top-defence-official-meets-bangladeshs-yunus-military-co-operation-discussed-second-bilateral-meet-in-a-year/articleshow/122326334.cms

[31] Jayanty Nada Shofa, “Turkish Defense Firm Baykar Inks Deal to Build Drone Factory in Indonesia”, Jakarta Globe, 12 February 2025. https://jakartaglobe.id/business/turkish-defense-firm-baykar-inks-deal-to-build-drone-factory-in-indonesia

[32] Reuters, “Indonesia Signs Contract with Turkey to Buy 48 KAAN fighter jets”, 29 July 2025. https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/indonesia-signs-contract-with-turkey-buy-48-kaan-fighter-jets-2025-07-29/

[33] Aditi Thakur, “The Türkiye–Pakistan Nexus — Strategic Implications for ‘Maritime’ India”, National Maritime Foundation, 14 June 2025. https://maritimeindia.org/the-turkiye-pakistan-nexus-strategic-implications-for-maritime-india/

[34] Hürcan Aslı Aksoy, Salim Çevik, and Nebahat Tanrıverdi Yaşar, “Visualising Turkey’s Activism in Africa”, Centre for Applied Turkey Studies, 03 June 2022. https://www.cats-network.eu/visualisations/visualising-turkeys-activism-in-africa

[35] Anne-Sophie Vial and Emile Bouvier, “Türkiye, the New Regional Power in Africa (3/3). A Military Presence that is now Greater than that of the Former European powers”, Appel aux dons, 06 March 2025. https://www.lesclesdumoyenorient.com/Turkiye-the-new-regional-power-in-Africa-3-3-A-military-presence-that-is-now.html

[36] Vivek Katju, “Why a Saudi-Pakistan Defence Pact doesn’t imply an ‘Islamic NATO’, The federal Voice of the States, 27 January 2026. https://thefederal.com/category/opinion/saudi-pakistan-defence-pact-turkey-islamic-nato-vivek-katju-227091

[37] Ito Mashino, “The Bipolar Conflict in the Middle East Over the Muslim Brotherhood”, Mitsui & Co Global Strategic Studies Institute Monthly Report, June 2021. https://www.mitsui.com/mgssi/en/report/detail/__icsFiles/afieldfile/2021/08/03/2106e_mashino_e.pdf

Also See: Kevin Truitte, “The New Major Middle East Divide: How Intra-Sunni Power Competition is Reshaping the Region”, Georgetown Security Studies Review, 18 February 2018. https://georgetownsecuritystudiesreview.org/2018/02/18/the-new-major-middle-east-divide-how-intra-sunni-power-competition-is-reshaping-the-region/

[38] Yousef Saba, “From Brothers to Rivals: Key Moments in Saudi-UAE Relations”, Reuters, 30 December 2025. https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/brothers-rivals-key-moments-saudi-uae-relations-2025-12-30/?

[39] Ahmed Elimam, Jana Choukeir, and Maha El Dahan, “Yemen’s Southern Separatists Call for Path to Independence Amid Fighting over Key Region”, Reuters, 03 January 2026. https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/saudi-envoy-says-leader-yemen-separatist-group-stc-blocked-delegations-aden-2026-01-02/

[40] Nadwa Al-Dawsari, “From Coalition to Confrontation: Saudi-UAE Rivalry in Yemen and its Regional Implications”, Middle East Institute, 05 January 2026. https://mei.edu/publication/from-coalition-to-confrontation-saudi-uae-rivalry-in-yemen-and-its-regional-implications

Also See: Luca Nevola, “Q&A: Southern Yemen: How Did We Get Here, and What Happens Next?”, ACLED, 15 January 2026. https://acleddata.com/qa/qa-southern-yemen-how-did-we-get-here-and-what-happens-next

[41] Anna Jacobs, “The Horn of Africa Needs an End to the Gulf’s Proxy Wars. Cooperation Is Key”, The Century Foundation, 17 November 2025. https://tcf.org/content/report/the-horn-of-africa-needs-an-end-to-the-gulfs-proxy-wars-cooperation-is-key

[42] Aidan Lewis, “Sudan conflict: what’s behind the war?”, Reuters, 13 July 2023. https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/whats-behind-sudans-crisis-2023-04-17

[43] Remi Dodd, “The UAE’s Long Game in East Africa, Rane, 13 August 2025. https://worldview.stratfor.com/article/uaes-long-game-east-africa

[44] Stasa Salacanin, “Saudi Arabia and the UAE Compete to be Hubs for Regional Business”, Stimson, 24 January 2025. https://www.stimson.org/2025/saudi-arabia-and-the-uae-compete-to-be-hubs-for-regional-business/

[45] Yousef Saba and Saeed Azhar, “Saudi Push on Company Headquarters Showing Success, Says Official”, Reuters, 24 October 2021. https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/saudi-push-company-headquarters-showing-success-says-official-2021-10-24/

[46] Michael Ratney, “A New Rift in the Gulf, and Only the Gulf Can Solve It”, CSIS, 16 January 2026. https://www.csis.org/analysis/new-rift-gulf-and-only-gulf-can-solve-it

[47] Dr. Abdulaziz Sager, “Saudi Arabia’s Diplomacy and the Changing World Order”, Gulf Research Center, 06 March 2025. https://www.grc.net/single-commentary/232

[48] Shivali Lawle, “The Rafale Forum: Operationalizing the India-France-UAE Trilateral”, Institute for Security and Development Policy”, 22 July 2025. https://www.isdp.eu/the-rafale-forum-operationalizing-the-india-france-uae-trilateral/

[49] Department of Commerce, Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Government of India, “Factsheet: India and European Union Trade Agreement”. https://www.commerce.gov.in/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/Factsheet-on-India-EU-trade-deal-27.1.2026.pdf

[50] Map from Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/place/Middle-East

[51] Ehud Yaari, “Recognizing Somaliland: Israel’s Return to the Red Sea”, The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, 16 January 2026. https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/recognizing-somaliland-israels-return-red-sea

[52] Air Marshal Anil Chopra, “Mediterranean QUAD: Will India Join 3+1 Grouping to Counter “Islamic NATO”? Can UAE Join in Amid Saudi Rift? OPED”, The Eurasian Times, 18 January 2026. https://www.eurasiantimes.com/mediterranean-quad-will-india-join-31-grouping/

[53] Map from Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/place/Middle-East

[54] Trading Economics. https://tradingeconomics.com/india/exports/saudi-arabia

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!