The Government of India’s application to the International Seabed Authority (ISA) on 18 January 2024, seeking approval for its plans-of-work for the exploration of polymetallic sulphides in the Carlsberg Ridge, and for cobalt-rich ferromanganese crusts at the Afanasy-Nikitin Seamount in the Central Indian Ocean, demonstrates increasing interest in India for minerals from the seabed.[1] The exploration and exploitation of mineral resources from the seabed — generally referred to as seabed mining — has been theoretically known since HMS Challenger’s discovery of polymetallic nodules on the ocean floor in 1876,[2] and its economic argument proposed in John L Mero’s “Mineral Resources of the Sea”[3] in 1965. Commercial exploitation, however, is yet to commence anywhere.[4] That said, the rapid acceleration in technology,[5] the strategic demand for critical minerals,[6] and commercial aspirations for exploiting new value-chains has increased the likelihood of commercial seabed mining.[7]

India has been an active participant in the exploration of seabed resources. The National Institute of Oceanography’s research vessel (RV), the RV Gaveshani, collected polymetallic nodules from the Indian Ocean in 1981[8] which, coupled with a capital investment of at least US$ 30 million, earned India the status of a ‘Pioneer Investor’. This granted her exclusive rights to identify, discover, and evaluate the technical and economic feasibility for exploitation of polymetallic nodules in the Central Indian Ocean Basin.[9] Since then, India has obtained two exploration licences from the ISA for the exclusive right to undertake exploration for polymetallic nodules and polymetallic sulphides in the Indian Ocean.[10] Additionally, India’s Deep Ocean Mission and Draft Blue Economy Policy Framework demonstrate New Delhi’s interest in deep-sea mining and provides policy guidance to the endeavour by emphasising the “development of technology for deep-sea mining, manned submersibles, and underwater robotics; technology innovations for exploration and conservation of deep-sea biodiversity; and deep-ocean survey and exploration”.[11] It needs to be noted that the idea of deep-sea mining includes both genetic and non-genetic (mineral) resources found in the deep-sea — i.e., within the water column as well as the seabed.[12] However, the scope of this paper is limited to the non-genetic mineral resources found on the seabed.

|

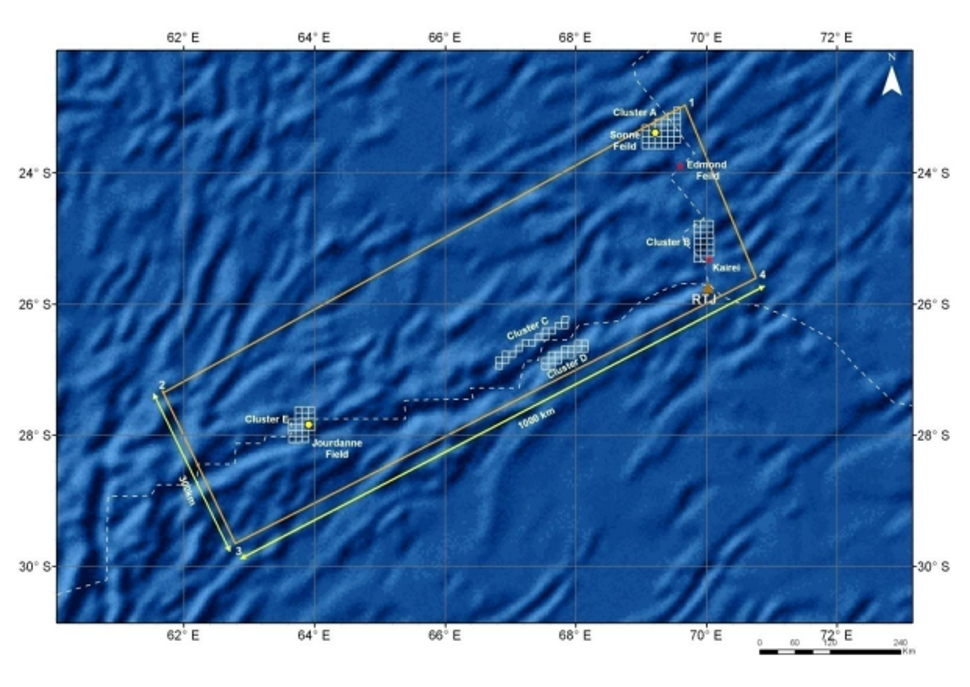

Source: ISA Contract for Exploration (Polymetallic Sulphides, Government of India) https://www.isa.org.jm/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Public-information-on-contracts-India_PMS.pdf

|

While the exploration stage relates primarily to survey, research, and resource estimation, efficient commercial exploitation requires a strong foundation of law and policy. With commercial mining an increasingly likely proposition (the ISA seeks to adopt exploitation regulations during its 30th Council Session in 2025)[13], India needs to have its domestic legal and policy structures in place to ensure readiness when exploitation does begin. This paper — split into two parts — focuses on the legal and institutional structures related to seabed mining both within India and internationally, and steps to be undertaken to reconcile India’s domestic law with its international obligations. The target audience for both parts of this paper is primarily the Ministry of Earth Sciences (and its associated autonomous institutions); the Ministry of Mines, the Ministry of Environment, Forest, and Climate Change; the Ministry of External Affairs; the National Security Council Secretariat; and the private industry in India. This — the first part — collates provisions of international law and established norms pertaining to seabed mining and seeks to furnish baseline information that will then be used to develop the analysis that will comprise the second part. In specific terms, Part 2 will delve into India’s national structures, explore the structures in foreign jurisdictions, and culminate in recommendations for Indian law.

Seabed Mining Within and Beyond National Jurisdiction

At the outset, it is important to highlight that limits of jurisdiction are legal fiction created over continuous geography, and seabed mining can occur both within and beyond areas of national jurisdiction. This limit, however, does have implications for the norms that govern similar activity. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea 1982 (UNCLOS) forms the overarching treaty through which seabed mining — both within and beyond national jurisdiction — is regulated. However, both these areas of jurisdiction are regulated distinctly, albeit within the same treaty. This notwithstanding, understanding the differences is important as the latter need to be correctly reflected in national legislations.

A key difference between the two jurisdictions in question lies in the right that coastal States exercise over the resources found in the respective jurisdictions. Article 1(1) (1) of UNCLOS defines the “Area” as the seabed and ocean floor and subsoil thereof, beyond the limits of national jurisdiction. Therefore, Article 1(1)(1) is a residual definition and addresses those areas that do not fall within identified limits of national jurisdiction. Hence, the delimitation of national jurisdiction, i.e., the outer limit of the legal continental shelf (LCS) is necessary to mark the points from which the international seabed or “Area” begins.

The seabed and subsoil of the submarine areas that extend beyond the territorial sea throughout the natural prolongation of the land territory of a coastal State to the outer edge of the continental margin, or to a maximum distance of 350 nautical miles (nm) from the baselines, has been classified as the continental shelf of a coastal State (Article 76 UNCLOS). States require to make an application to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS) whose recommendations will finally establish the outer limits of the continental shelf of each coastal State.

|

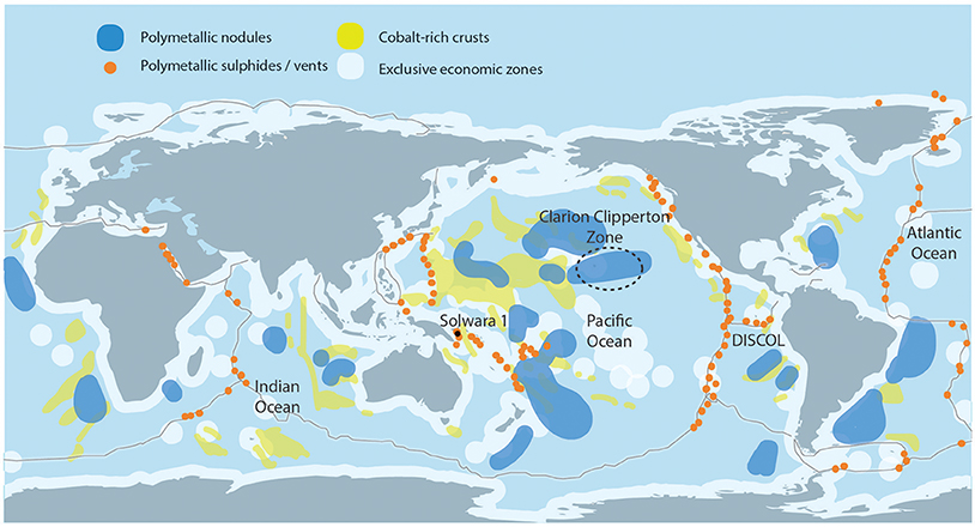

Source: J Hein, K Mizell, A Koschinsky, and T Conrad, (2013). Deep-ocean mineral deposits as a source of critical metals for high- and green-technology applications: comparison with land-based resources. Ore Geol. Rev. 51, 1–14

|

The coastal State exercises exclusive “sovereign rights” for the purposes of exploring and exploiting its “natural resources” which includes “mineral and other non-living resources of the seabed and subsoil” and does not depend on occupation or express proclamation (Article 77 UNCLOS). In contrast, the resources of the Area — defined as “solid, liquid or gaseous mineral resources in situ in the Area at or beneath the seabed, including polymetallic nodules” (Article 133 (a) UNCLOS) — are the “common heritage of mankind” (Article 136 UNCLOS), and a claim or exercise of sovereignty or sovereign rights over the Area or its resources is expressly prohibited (Article 137 UNCLOS). Hence, we see a distinction in not only the right over the resources but also the type of resources over which such right is exercised.

Sovereign rights over resources entails that States are free to extract and dispose these resources without any external interference.[14] They are entitled to the resources and the proceeds of sale of those resources. A minor difference exists for the continental shelf beyond 200 nm where a coastal State (except a developing State who is a net importer of a mineral resource produced from its continental shelf) has to make a payment or contribution to the ISA from the total value or volume of production (Article 82 UNCLOS). This mechanism developed as a compromise considering that a claim for an extended continental shelf encroaches on the Area, the resources of which are the common heritage of mankind.[15] This principle, in the form it is encapsulated within UNCLOS, vests rights in humankind as a whole over the resources of the Area, with equitable sharing of benefits from the exploitation of these resources — with particular regard to the interests of developing States — through a common management regime (Article 136, 137, 140, and 156 UNCLOS).[16] This is distinct from the regime in UNCLOS pertaining to fishing in the high seas where, while no one State has exclusive rights over the resources, they are not prohibited (barring environmental protection norms) from extracting resources from the water column and exercising property rights over such resources once extracted.

Further, the inclusion of other non-living resources within the continental shelf as within the scope of coastal State’s sovereign rights is perceived to include a broader category of resources that may not be considered mineral in nature. This could include hydrocarbons, sand, coral, or aggregate rock.[17] Such non-inclusion in the Area regime of other non-mineral resources poses questions about the management regime for hydrocarbons in the international seabed Area which is increasingly becoming a likely proposition.[18] The non-consideration of hydrocarbons in the discussions within the ISA may point to these resources being out of its scope of work. However, the provision declaring the Area, too, as common heritage of mankind may preclude a first-come-first-served mechanism for hydrocarbon exploitation in the Area.[19]

These distinctions have implications for the roles that national and international law play in regulation of this activity and the institutional structuring for this activity. Naturally, mining within national jurisdiction is primarily regulated by national legislation of the coastal State, while that beyond national jurisdiction lies predominantly within the ambit of international law. However, international law too, imposes obligations on coastal States for activities within its continental shelf and national law has important implications for regulating seabed mining beyond national jurisdiction.

International Law – Institutions and Obligations

The Area. In consonance with the principle of common heritage of mankind, UNCLOS establishes the ISA through which the State parties organise and control the activities in the Area, particularly with a view to the administration of its resources (Article 156, 157 UNCLOS). Hence, the ISA serves as the common management structure through which seabed mining in the Area is regulated.

The norms for seabed mining are found in Part XI, Annex III and IV of UNCLOS, and the subsequently concluded 1994 Agreement relating to the Implementation of Part XI of UNCLOS.[20] Additionally, Article 153 (1) UNCLOS states that activities in the Area, i.e., all activities of exploration-for and exploitation-of the resources of the Area “shall be organized, carried out and controlled… in accordance with this article as well as other relevant provisions of this Part and the relevant Annexes, and the rules, regulations and procedures of the Authority.” This gave rise to the “Mining Code” of the ISA, which thus far includes three regulations for exploration (and prospecting) of resources, since exploration represents the first phase of any mining activity.[21] Each regulation pertains to a particular mineral resource, i.e., polymetallic nodules,[22] polymetallic sulphides,[23] and cobalt rich ferro-manganese crusts.[24] Regulations for exploitation — which constitute the recovery and extraction for commercial purpose of minerals from resources in the Area along with its supporting processes — still remain to be adopted.[25]

As per Article 153 (2) (b) of UNCLOS, activities within the Area (both exploration and exploitation) may be carried out by (i) State parties or State enterprises, or (ii) natural or juridical persons who are either nationals of the State party or effectively controlled by nationals of the State party when sponsored by the State. In order to undertake these activities, a formal written plan of work, in addition to a sponsorship agreement,[26] needs to be submitted which, when authorised by the ISA, takes the form of a contract (Article 153(3) UNCLOS). Therefore, this creates (a) the distinction between a ‘Contractor’ and a ‘Sponsoring State’ and (b) additional contractual obligations on the Contractor both from the exploration/exploitation contract with the ISA and the sponsorship agreement with the State party. It is possible that the State party itself submits the plan of work and acquires the status of both sponsoring State and Contractor too (as is in India’s case).[27]

The responsibilities-of and obligations-on State parties, with respect to activities in the Area, were dealt with extensively in the Advisory Opinion of the Seabed Disputes Chamber on the Responsibilities and obligations of States sponsoring persons and entities with respect to activities in the Area.[28] While the nature of sponsorship has not been clarified in text of the Convention itself, the language of the advisory opinion seems to suggest a legal commitment or backing rather than financial or administrative sponsorship. The rationale underpinning the requirement for sponsorship is to ensure that natural or legal persons, who generally do not enjoy international legal personality and thus are not strictly under the purview of international law, are obligated to follow the norms stipulated in the Convention as well as the Mining Code, by the domestic legal system.[29] The stipulation of sponsorship makes the process of enforcement more effective due to the tools available within the domestic legal systems of States. Hence, the role of domestic legal systems becomes critical in the entire international regulatory scheme.

State parties have two kinds of obligations under the international legal regime, namely, (i) the responsibility to ensure compliance by sponsored contractors (with the terms of the contract and the obligations set out in the Convention and related instruments), and (ii) direct obligations of State parties.[30] The obligation to “ensure”, set out in Article 139 of the UNCLOS, has been interpreted as an obligation of conduct and due diligence rather than that of result.[31] It does not require compliance by the contractor in each and every case but rather it is an obligation to deploy adequate means to exercise the best possible efforts and to do the utmost to obtain this result. According to the Seabed Disputes Chamber, the “due diligence” obligation “to ensure” requires the sponsoring State to take measures within its legal system and that the measures must be “reasonably appropriate”.[32] The reasoning is drawn from the provisions of Article 153 paragraph 4 and Annex III, Article 4, Paragraph 4, which explicitly requires the sponsoring State to adopt “laws and regulations” and to take “administrative measures” that are within the framework of its legal system, reasonably appropriate to securing compliance. Further, In the Pulp Mills on the River Uruguay Case, it was held that an obligation of due diligence “entails not only the adoption of appropriate rules and measures, but also a certain level of vigilance in their enforcement and the exercise of administrative control applicable to public and private operators, such as the monitoring of activities undertaken by such operators”.[33] This concept is a variable that may change over time in the light of new scientific or technical knowledge and also in relation to the risks involved in that activity.[34] These measures must be enacted in good faith and cannot be less stringent than the applicable legal regime.[35] Therefore, mining for different kinds of minerals may require different standards of diligence which may have to be higher for riskier activities.

The direct obligations of States are primarily: [36]

(1) The obligation to assist the Authority in the exercise of control over activities in the Area (Article 153 Paragraph 4).

(2) The obligation to apply a precautionary approach (Regulation 31, Paragraph 2, of the “Nodules Regulations”, and Regulation 33, Paragraph 2, of the “Sulphides Regulations”). The obligation is a codification of Principle 15 of the Rio Declaration, which essentially requires that “where there are threats of serious or irreversible damage, lack of full scientific certainty shall not be used as a reason for postponing cost-effective measures to prevent environmental degradation.” This obligation is applicable to the Authority, the sponsoring State, and the Contractor (Section 5.1 Annex 4, “Sulphides Regulations”).

(3) The obligation to apply best environmental practices (Regulation 33, Paragraph 2, of the “Sulphides Regulations”). In addition to the application of best environmental practices, Article 209 of the UNCLOS requires that the coastal State enact laws and regulations to prevent, reduce, and control pollution of the marine environment from activities in the Area not only under their sponsorship but also from activities undertaken by vessels, installations, structures, and other devices flying their flag or of their registry.

(4) The obligation to take measures to ensure the provision of guarantees in the event of an emergency order by the Authority for protection of the marine environment (Regulation 32, Paragraph 7, of the “Nodules Regulations”, and in Regulation 35, Paragraph 8, of the “Sulphides Regulations”). This obligation is to ensure that the sponsoring State has the ability to either mandate the Contractor to guarantee protection of the marine environment, or for the State to be able to take prompt emergency measures towards this end.

(5) The obligation to ensure the availability of recourse for compensation in respect of damage caused by pollution (Article 235 Paragraph 2). This seeks to secure remedy within national legal systems for any damage caused by the Contractor in line with their obligations under Annex III Article 22 of UNCLOS to provide reparation for damages caused by wrongful acts committed in the Area.

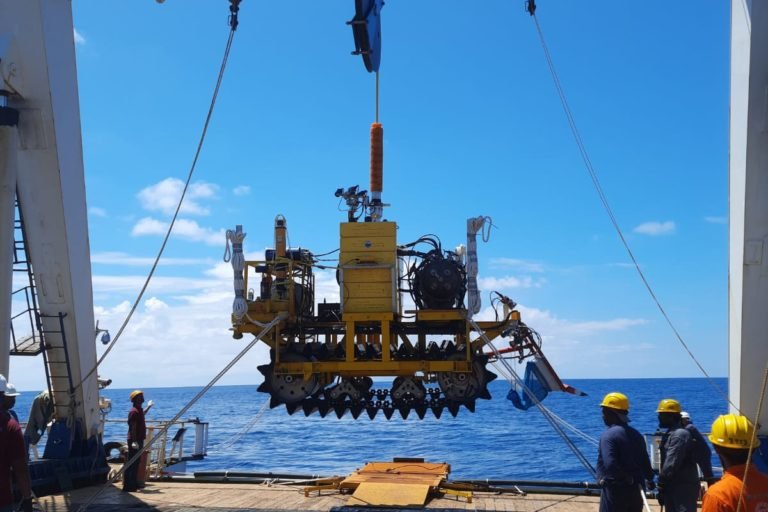

(6) The obligation to conduct environmental impact assessments. While the Contractor is required to submit an assessment of the potential environmental impacts of the proposed activity,[37] the sponsoring States have a direct obligation to “cooperate with the Authority in the establishment and implementation of programmes for monitoring and evaluating the impacts of deep seabed mining on the marine environment”.[38] Reading this in conjunction with Article 139 of UNCLOS, the sponsoring State has the twin obligation to establish and implement monitoring programmes, and ensure that the Contractor conducts the environment impact assessment. Fulfilling the former also requires the creation of “impact reference zones” and “preservation reference zones” (Regulation 31 of the “Nodules Regulations” and Regulation 33 of the “Sulphides Regulations’). “Impact Reference Zones” are areas to be used for assessing the effect of activities in the Area on the marine environment and require to be representative of the environmental characteristics of the Area. “Preservation Reference Zones” imply areas in which no mining is permitted to occur so as to ensure representative and stable biota of the seabed, in order to assess any changes in the biodiversity of the marine environment. The “Legal and Technical Commission” of the ISA has developed “Recommendation for the guidance of contractors for the assessment of the possible environmental impacts arising from exploration for marine minerals in the Area (ISBA/25/LTC/6) (EIA Recommendations)”,[39] which details activities that require an impact assessment, baseline data requirements, and the data collection, reporting and archival protocol. These recommendations pertain to the activity of exploration. However, the environmental impact assessment (EIA) for the exploitation stage is yet to be finalised.[40] In January 2020, in compliance with the EIA Recommendations, India submitted an environmental impact statement to the ISA while testing a nodule collector pre-prototype machine in the Central Indian Ocean Basin (CIOB).[41]

Underscoring the importance of environmental protection and management, the ISA Council has also adopted a “Regional Environmental Management Plan” (REMP) identifying “Areas of Particular Environmental Interest” within which no application of a formal plan of work shall be accepted, in order to protect the seabed in those regions.[42] Currently, only an REMP for the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ) has been developed where thirteen such zones have been identified, with four more (Indian Ocean Triple Junction, Northwest Pacific Ocean, Northern Mid-Atlantic Ridge, and South Atlantic Ocean) being under development.

While these direct obligations are distilled and treated as separate obligations from the “responsibility to ensure”, they are critical to fulfilling the “due diligence” obligation under Article 139 of the UNCLOS. Further, while UNCLOS and the ISA Mining Code is the central regulatory regime for deep seabed mining, it is far from being the only international regime applicable to the activity. While interpreting the scope of the term “activities in the Area”, the Seabed Disputes Chamber concluded that it included the recovery of minerals from the seabed and their lifting to the water surface, and activities directly connected with these processes such as the evacuation of water from the minerals and the preliminary separation of materials of no commercial interest, and their disposal at sea. Interestingly, it was held that transportation to points on land from the part of the high seas superjacent to the part of the Area in which the contractor operates cannot be included in the notion of “activities in the Area”.[43] This aspect would be covered by IMO regulations on safety of navigation, pollution, and bulk cargo. It includes the Convention on the Safety of Life at Sea, The International Maritime Solid Bulk Cargoes Code, and the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships, to name a few. Therefore, all these measures need to form a part of the national legal and administrative measures taken by the sponsoring State.

Continental Shelf. For seabed mining within national jurisdiction, the nature of rights over resources results in greater coastal State control over the mechanism through which seabed mining is regulated. The sovereign right of States to exploit their natural resources needs to be in accordance with their duty and the general obligation to protect and preserve the marine environment (Article 193 and 194 of UNCLOS). This includes taking measures against pollution from vessels, and “from installations and devices used in exploration or exploitation of the natural resources of the seabed and subsoil in particular measures for preventing accidents and dealing with emergencies, ensuring the safety of operations at sea, and regulating the design, construction, equipment, operation and manning of such installations or devices” (Article 194 (c) UNCLOS).

This reiterates the criticality of national legislation in the entire regulatory scheme for seabed mining. In India, seabed mining is broadly covered by the Offshore Areas Mineral (Development and Regulation) Act, 2002.[44] However, the scope of the Act covers “offshore areas” which as per s4(n) are defined as the “territorial waters, continental shelf, exclusive economic zone and other maritime zones of India under the Territorial Waters, Continental Shelf, Exclusive Economic Zone and Other Maritime Zones Act, 1976 (80 of 1976)”. This prima facie implies that this Act applies to minerals within India’s maritime zones and any activity in the international seabed Area falls outside the scope of the present Act.

The second part of this paper will explore the nuances of the national regime in India, compare and contrast it with national legislations in other jurisdictions that are important players in this sector, and make recommendations on how the legislative and administrative framework within India is to adapt to prepare India for capitalising on a nascent yet critical industry.

*****

About the Author:

Soham Agarwal, a Delhi-based lawyer, holds a Bachelor of Law (Honours) degree from the University of Nottingham, UK. He is currently an Associate Fellow with the “Public International Maritime Law” (PIML) Cluster of the National Maritime Foundation, New Delhi. His research focuses upon the seabed, maritime infrastructures, and seabed warfare. He may be contacted at law10.nmf@gmail.com

Endnotes

[1] International Seabed Authority, “The Government of India submits two applications for approval of plans of work for seabed exploration in the Indian Ocean”, ISA Press Release, 18 January 2024. https://www.isa.org.jm/news/the-government-of-india-submits-two-applications-for-approval-of-plans-of-work-for-seabed-exploration-in-the-indian-ocean/

[2] John Murray and Alphonse François Renard, “Report on Deep-Sea Deposits Based on the Specimens Collected During the Voyage of HMS Challenger in the Years 1872 to 1876”, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 04 November 1891 https://epic.awi.de/id/eprint/38636/2/challenger-report_1891.pdf

[3] John Mero, “Mineral Resources of the Sea”, Elsevier Oceanography Series, 1, (1965). https://www.sciencedirect.com/bookseries/elsevier-oceanography-series/vol/1

[4] James R Hein and Pedra Madureira et al, “Changes in seabed mining” in The Second World Ocean Assessment Volume II, (New York, United Nations Publications, 2021), 257-259 https://www.un.org/regularprocess/sites/www.un.org.regularprocess/files/2011859-e-woa-ii-vol-ii.pdf

[5] Koen Rademaekers et al., Deep-seabed exploitation: Tackling economic, environmental and societal challenges, European Parliamentary Research Service, Scientific Foresight Unit (STOA) March 2015 https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2015/547401/EPRS_STU(2015)547401_EN.pdf

[6] Thea Dunlevie, “The Importance of Seabed Critical Minerals for Great Power Competition”, Center for Maritime Strategy, September 05, 2023. https://centerformaritimestrategy.org/publications/the-importance-of-seabed-critical-minerals-for-great-power-competition/

[7] Michael Lodge, “The International Seabed Authority and Deep Seabed Mining”, Our Ocean, Our World, Nos. 1 & 2 Volume LIV, (May 2017). https://www.un.org/en/chronicle/article/international-seabed-authority-and-deep-seabed-mining

[8] Dr S Rajan, “Polymetallic Nodules Resource Classification: Proceedings of the International Seabed Authority and Ministry Of Earth Science, Government Of India Workshop Held In Goa, India 13-17 October 2014”, International Seabed Authority, 1 (2017) https://www.isa.org.jm/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/goa-20aug2018_0.pdf

[9] “Resolution II Governing Preparatory Investment in Pioneer Activities Relating to Polymetallic Nodules”, Final Act of the Third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea, United Nations Convention of the Law of the Sea (1982) https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/final_act_eng.pdf

[10] “Exploration Contracts”, International Seabed Authority, accessed on 12 February 2024 https://www.isa.org.jm/exploration-contracts/

[11] “Deep Ocean Mission”, Schemes, Ministry of Earth Sciences, accessed on 13 February 2024 https://moes.gov.in/schemes/dom?language_content_entity=en

[12] Koen Rademaekers et al., “Deep-seabed exploitation”, 1

[13] International Seabed Authority, “Corrigendum – ISA Council closes Part II of its 28th Session”, ISA Press Release, 24 July 2023. Also see “Nations aim to ink deep sea mining rules by 2025”, The Hindu, July 23, 2023. https://www.thehindu.com/news/international/nations-aim-to-ink-deep-sea-mining-rules-by-2025/article67110597.ece

[14] Dr. Danae Azaria, The Scope, and Content of Sovereign Rights in relation to Non-Living Resources in the Continental Shelf and the Exclusive Economic Zone, Journal of Territorial and Maritime Studies; (2016)

[15] International Seabed Authority, “Technical Study 5: Non-living resources of the Continental Shelf beyond 200 nautical miles: speculations on the implementation of article 82 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea” (2010). https://www.isa.org.jm/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/techstudy5.pdf

[16] John E Noyes, The Common Heritage of Mankind: Past, Present, and Future, 40 Denver J. Int’l L. & Pol’y 447 (2011).

[17] ” International Law Association, Rio de Janeiro Conference Report (2008)

[18] MC Baker et al., “The status of natural resources on the high seas”, WWF/IUCN, (2001) https://www.unclosuk.org/sites/unclosuk/files/documents/HIGHSEAS.PDF

[19] David M Ong, “OUTER CONTINENTAL SHELF”, Rio De Janeiro Conference, International Law Association, (2008) https://www.ila-hq.org/en_GB/documents/conference-report-rio-de-janeiro-2008-7

[20] Klaas Willaert, “Regulating Deep Sea Mining: A Myriad of Legal Frameworks” (Switzerland: Springer Cham, 2021)

[21] Koen Rademaekers et al., “Deep-seabed exploitation”, 2

[22] ISA Council, “Decision of the Council of the International Seabed Authority relating to amendments to the Regulations on Prospecting and Exploration for Polymetallic Nodules in the Area and related matters”, 2013 ISBA/19/C/17 (Nodules Regulation)

[23] ISA Assembly, “Decision of the Assembly of the International Seabed Authority relating to the regulations on prospecting and exploration for polymetallic sulphides in the Area”, 2010 ISBA/16/A/12/Rev. 1 (Sulphides Regulation)

[24] ISA Assembly, “Decision of the Assembly of the International Seabed Authority relating to the Regulations on Prospecting and Exploration for Cobalt-rich Ferromanganese Crusts in the Area” 2012 ISBA/18/A/11 (Cobalt Crusts Regulation)

[25] ISA Legal and Technical Commission, “Draft Regulations on Exploitation of Mineral Resources in the Area”, ISBA/25/C/WP.1 (Exploitation Regulations)

[26] Regulation 9 Nodules Regulation and Regulation 11 of Sulphides Regulation.

[27] “ISA Contract for Exploration, Public Information Template” (Government of India, Polymetallic Nodules), International Seabed Authority, accessed on February 17, 2023 https://www.isa.org.jm/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Public-information-on-contracts-India_PMN.pdf

[28] International Tribunal of the Law of the Sea, “Responsibilities and Obligations of States Sponsoring Persons and Entities with respect to Activities in the Area”, Advisory Opinion. ITLOS Rep 2011:10 https://www.itlos.org/fileadmin/itlos/documents/cases/case_no_17/17_adv_op_010211_en.pdf

[29] Advisory Opinion para 75

[30] Advisory Opinion p 74

[31] Advisory Opinion pp 110

[32] Advisory Opinion pp 120

[33] International Court of Justice, Pulp Mills on the River Uruguay (Argentina v. Uruguay), Judgment. ICJ Rep 2010:14 (2010) Para 197

[34] Advisory Opinion – pp 117

[35] Advisory Opinion pp 230

[36] Advisory Opinion 122

[37] Section 1, Paragraph 7, of the Annex to the 1994 Implementation Agreement

[38] Regulation 31, paragraph 6, of the Nodules Regulations and Regulation 33, paragraph 6, of the Sulphides Regulations

[39] ISA Legal and Technical Commission, “Recommendations for the guidance of contractors for the assessment of the possible environmental impacts arising from exploration for marine minerals in the Area”, (Kingston, 2019). https://www.isa.org.jm/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/26ltc-6-rev1-en_0.pdf

[40] ISA Legal and Technical Commission, “Draft Standard and Guidelines for environmental impact assessment process”,, (Kingston, 2022) https://www.isa.org.jm/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Standard_and_Guidelines_for_environmental_impact_assessment-rev1.pdf

[41] Dr Rahul Sharma and Dr B Nagendra Nath, “Environmental Impact Statement- Environmental conditions and likely impact in the area selected for nodule collection trials at the Indian PMN site in the Central Indian Ocean Basin”, Ministry of Earth Science, Government of India, (January 2020). https://www.isa.org.jm/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/India_PMN_EIS_Jan2020.pdf

[42] ISA Council, “Decision of the Council of the International Seabed Authority relating to the review of the environmental management plan for the Clarion-Clipperton Zone”, (Kingston, December 2021). https://www.isa.org.jm/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/ISBA_26_C_58_E.pdf

[43] Advisory Opinion 96

[44] The Offshore Areas Mineral (Development and Regulation) Act, 2002 (Act No. 17 of 2003)

Fig 1: India’s Exploration Area for Polymetallic Sulphides in the Indian Ocean Ridge

Fig 1: India’s Exploration Area for Polymetallic Sulphides in the Indian Ocean Ridge Fig 2: Seabed Resources Beyond Areas of National Jurisdiction

Fig 2: Seabed Resources Beyond Areas of National Jurisdiction

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!