(A Hindi version of this article has been published in the September 2023 issue of “Defence Monitor”, a leading Hindi language defence magazine published in India. This English version is published with permission of the Editor, Defence Monitor).

In analysing the Indian Navy’s functioning in the changing geopolitics of the Indo-Pacific, it would be prudent to first ensure conceptual clarity in respect of “geopolitics” itself and to establish exactly what one means by the expression “the Indo-Pacific”.

It is a common mistake to consider geopolitics, geoeconomic, and geostrategy as three separate choices and to debate whether something (China’s Belt and Road Initiative, for example) is a geopolitical move or a geoeconomic one or a geostrategic one. Such debates are conceptually flawed because the truth is that every nation has a set of geoeconomic objectives and complementary set of non-geoeconomic objectives that it wishes to attain. While geoeconomic objectives are fairly self-evident, examples of non geoeconomic objectives might include prestige, cultural connectivity, people-to-people engagement, and so on. The nation in question now formulates “strategies” by which it would attain these geoeconomic objectives as also its non-geoeconomic ones. A “strategy” differs from a “plan”. A “plan” will always address questions such as “What is to be done?”, “Who is to do it?”, “Where does it have to be done?” “When does it have to be done?”, “For how long does it have be done?”, and so on. A “strategy”, on the other hand, not only provides answers to these very same questions, but in addition, answers the critical question, “why is it being done?”. In addition, of course, a “strategy” will often contain numerous subordinate “plans” that are spread over space and time. When these strategies need to be executed through interactions outside of the country’s border, they become known as “geostrategies”. It is obvious, therefore that “geostrategy” lies at a lower level than “objectives” (whether geoeconomic or non-geoeconomic ones) and one cannot make a choice between the two. It is also important to note that “strategic” is an adjective and cannot exist without its noun, namely, “strategy”. Having formulated one or more geostrategies, the nation now tries to guarantee (to the extent that it can) that these geostrategies will, in fact, succeed. It does so by putting in place a set of “assurance” mechanisms. At the same time, the nation also tries to guard against the adverse fallout should one or more of these geostrategies fail. It does so by putting in place a set of “insurance” mechanisms. These “assurance” and “insurance” mechanisms constitute the nation’s “foreign policy”. There are only two instruments of any nation’s foreign policy. One is “diplomacy” and the other is the “military”. Both these instruments lie at a level below “geostrategy” in that they are the means by which a geostrategy is moved towards success and away from failure. This entire typological structure from the determination of geoeconomic and non-geoeconomic goals to the formulation of the geostrategies to attain these goals and the assurance and insurance mechanisms that will support the geostrategies that have been formulated, is now known as “geopolitics”. Every geostrategy must fit into some geographical context. This brings us to the “Indo-Pacific”.

Thanks to the pervasive grip that the USA, as the planet’s sole hyperpower, has over media-driven imagination across the world, many people understand the “Indo-Pacific” to be as had been conceptualised by the US administration led by the erstwhile President, Donald Trump. He conceptualised the “Indo-Pacific” as a “geostrategy” that was designed to contest the aggressive rise of China. In sharp contrast, however, India does not conceptualise or view the “Indo-Pacific” as being in and of itself a geostrategy. India perceives the “Indo-Pacific” as a “strategic geography” within which India formulates and executes a number of “geostrategies” designed to achieve its own set of geoeconomic and non-geoeconomic goals that would promote the economic, material, and societal wellbeing of the people of India. India firmly believes that the Indian economy cannot rise without the simultaneous rise of the economies of our region. In other words, it does not believe that the Indian economy can ride upon the crest of a wave while the economies of its neighbours within the region are wallowing in some trough. This region-wide “desired end-state” — one of sustained and sustainable economic growth within an environment of stability and security — is given expression through the acronym “SAGAR”, which stands for “Security And Growth for All in the Region”[1] and is, consequently, the “maritime policy” of India. The “region” in question is the “Indo-Pacific”. For India, as also for an increasing number of nations, the “Indo-Pacific” is a predominantly (but not exclusively) maritime expanse that encompasses the entire Indian Ocean and the entire Pacific Ocean. It accordingly stretches, as was clearly enunciated by Prime Minister Modi in 2018, from the eastern shores of Africa to the western shores of the Americas.[2] It is within this space that India formulates its several geostrategies, and the Indo-Pacific is, therefore, for India, a single “strategic” space.

Seven contemporary geopolitical trends have contributed to the changing geopolitical context of the Indo-Pacific. The first is the assertiveness and military aggressiveness of the rise of China and the global apprehension that this aggressiveness will not be limited to the South China Sea and the East China Sea alone but will spread across the entire maritime expanse of the Indo-Pacific. The second is the effort of the US, its allies, and its like-minded partners, including India, to balance China and maintain a status quo that is founded upon comity amongst nations — which itself is built upon a respect-for and adherence-to a consensually-derived rules-based order, especially (although not limited to) the maritime domain. China, too, has been trying to muster a grouping of like-minded countries (Russia, North Korea, Pakistan, Turkey, and possibly Iran) that are opposed to the US even if they are not overtly pro-Beijing. The third is the rise of India as a global economy with significant dependence upon maritime merchandise trade. The fourth is the increasing involvement of the European Union as a serious maritime-security stakeholder in the Indo-Pacific. The fifth is the impact of the ongoing Russia-Ukraine armed conflict upon supply chains and value chains throughout the Indo-Pacific. The sixth is the adverse impact of climate change, especially as manifested in extreme-weather events and sea-level rise. The seventh is the impact of pandemics such as COVID-19 — as also its predecessors and, far more worryingly, its successors — and their impacts upon regional economies through restrictions in global trade, maritime connectivity, and regional health.

This brings us to the “assurance” and “insurance” mechanisms. As has already been mentioned, these mechanisms are the two instruments by which the foreign policy of every nation (including, of course, India) is executed, namely, “diplomacy” and the “military”. It would be a profound error to think that these are two mutually exclusive instruments, wherein diplomacy is exercised to avoid armed conflict while the military is used to prosecute armed conflict. The truth, of course, is that the military is very frequently is used (through dissuasion, deterrence, and defence-diplomacy) to prevent conflict, while diplomacy could and often is used to shape the external security or military environment so as to favourably influence one’s national endeavours in the run-up to armed conflict and even during the prosecution of armed conflict.

Insofar as diplomacy is concerned, in attempting to deal with the seven factors outlined above, a growing number of countries (as also collectives such as ASEAN and the EU) have promulgated outlooks, guidelines, strategies, and initiatives, which are specifically contextualised to the Indo-Pacific. These include ASEAN, Australia, Bangladesh, Canada, the EU, France, Germany, India, Japan, the Netherlands, South Korea, and the US. Another major diplomatic trend is that while not abandoning major multilateral forums, countries located within the Indo-Pacific geography, as well as those who have national interests in this predominantly maritime expanse, are gravitating towards minilateral groupings such as the Quad (Australia, India, Japan, and the US), the SCO,[3] the I2U2 (India, Israel, USA, and the UAE), the Colombo Security Conclave,[4] AUKUS (Australia, the UK, and the US), as also a variety of trilaterals, many of which involve India (e.g., India-Japan-Australia; India-Japan-Italy; India-Japan-USA; India-France-Australia; India-Indonesia-Australia; India-France-UAE; India-Maldives-Sri Lanka; etc.)

Turning now to “insurance” mechanisms, although within the Maritime Zones of India, the Indian Navy works in seamless coordination with the Indian Coast Guard and a number of other maritime agencies of the country, in maritime spaces beyond the country’s Legal Continental Shelf, the Indian Navy is the sole maritime manifestation of the sovereign power of the Republic. Since the Indo-Pacific is a predominantly maritime space, the Indian Navy is India’s option of choice to undertake shaping-operations through naval diplomacy designed to signal national intent, as also to reassure, dissuade, and deter wherever appropriate and necessary. In many ways, “Reassurance” is the converse of “Deterrence” in that the former seeks to convince an ally or partner that it will, indeed, be supported in the face of coercion or aggression, but like deterrence, the success of reassurance is crucially dependent upon perceptions of capacity, capability, and resolve.

Where India and her navy are concerned, even amidst the rapidly changing dynamics of the Indo-Pacific, as described thus far, there are three great constants. The first is that India’s principal national interest remains the economic, material, and societal wellbeing of the people of India.[5] The second is that as a maritime nation, India’s principal maritime interest remains freedom from threats arising in the sea or from the sea or through the sea. (These threats could be manmade ones incorporating a slew of traditional and non-traditional aspects, they could also be natural ones such as cyclones and tsunamis, and they could even be combinations of these two, such as maritime impacts of climate-change, ocean acidification, ocean pollution, overfishing and illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing, etc.). The third is that India’s eight principal maritime objectives remain unchanged, namely: (1) protection from sea-based threats to India’s territorial integrity; (2) Stability (peace & prosperity) in India’s maritime neighbourhood; (3) the creation, development, and sustenance of a ‘Blue’ Economy that is resilient against adverse maritime effects of climate-change; (4) the preservation, promotion, pursuit and protection of offshore infrastructure and maritime resources within and beyond the Maritime Zones of India (MZI); (5) the promotion, protection and safety of India’s overseas and coastal seaborne trade including her Sea Lines of Communication (SLOCs), and, the ports that constitute the nodes of this trade; (6) support to marine scientific research, including that in Antarctica and the Arctic; (7) the provision of support, succour, and extrication-options to the Indian diaspora; and (8) obtaining and retaining a favourable geostrategic maritime-position.[6]

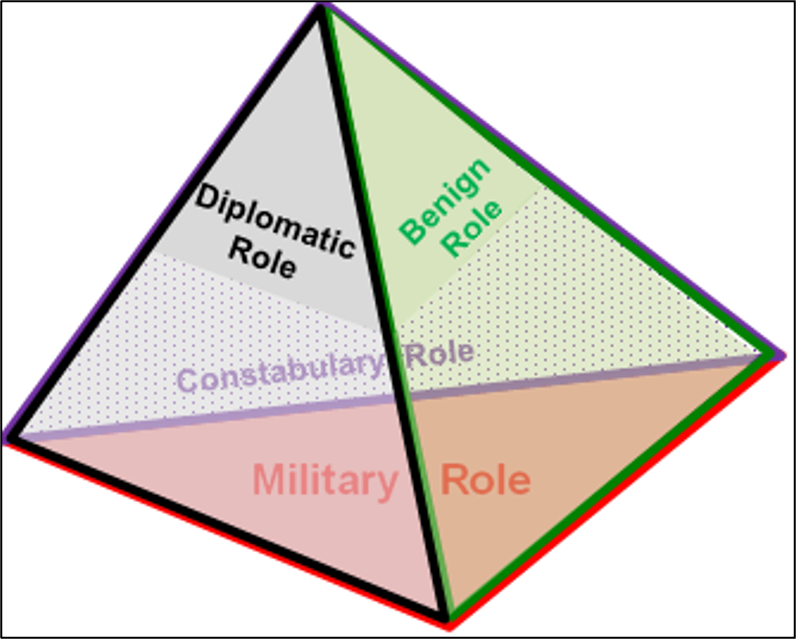

The consequence of the changing geopolitics juxtaposed against the three constants just described is that the criticality of all four roles (the military role, the diplomatic role, the constabulary role, and the benign role) of the Indian Navy is underscored more than ever. These four roles of the Indian Navy are often represented by the four faces of a solid pyramid, as shown in Figure 1. The military role is the base, while the remaining three faces respectively represent the diplomatic role, the constabulary (policing) role, and the benign (humanitarian) role.

|

Fig 1: The Solid Pyramid of Roles Source: Author |

As an all-round balanced force, the sheer competence, steadfastness, determination, and resolve of the Indian Navy and the demonstration of these competencies in several significant operations, as also in numerous combined exercises conducted throughout the Indo-Pacific with foreign navies of considerable military renown, have cemented its reputation as the preferred security partner throughout the Indian Ocean. In the western Pacific, too, its reputation is steadily growing.

It is this enormously favourable perception that makes the Indian Navy such an attractive partner for the US and its allies as they strive to deal with the assertiveness and military aggressiveness of the rise of China. They recognise that the Indian Navy is quite competent to hold its own in the western segment of the Indo-Pacific, thereby enabling them to concentrate upon the western and southern Pacific Ocean in general and the South- and East China Seas in particular. The growth of the hardware (capacity) of the Indian Navy is impressive by any standard, as may be seen from the following Order of Battle (ORBAT) of major combatants, to which the latest inductions of 26 Rafale carrier-borne fighter jets and three follow-on AIP-equipped Scorpene Class diesel-electric submarines will add considerable additional heft in the coming few years:[7]

02 x Aircraft Carriers [Air Wing Fighter: MiG 29K] (+ 1-3 planned for induction) [Air Wing Fighter: Rafale-M]

11 x Guided-missile Destroyers (+ 8 [Project 18] planned for induction)

12 x Guided-missile Frigates (+ 11 [Project 17A & Project 1135.6] under construction / planned for induction)

07 x Guided-Missile Corvettes (+ 07 under construction / planned for induction)

07 x Guided-Missile ‘Light Corvettes’ (+ 6 under construction / planned for induction)

04 x ASW Corvette

01* x ASW ‘Light-Corvettes’ (+ 16 under construction / planned for induction)

10 x Offshore Patrols Vessels [OPVs] (+ 5 under construction / planned for induction)

01 x LPD (+ 4 x LPD under procurement / planned for induction)

03 x LST (L)

04 x LST (M)

04 x Fleet Tankers (+ 05 under construction / planned for induction)

02 x Nuclear-powered submarines (+ 11 under construction / planned for induction)

17 x Diesel-Electric submarines (+ 09 under construction / planned for induction)

Major Airborne Combatants

41 x MiG-29K/KUB (+ 4 planned for induction)

(+ Induction of 23 Carrier-borne Rafale-M fighters in progress)

12 x P-8 (India)

25 x Dornier-228 (+ 12 planned for induction)

08 x Dhruv Mk-1 (+ 33 Mk-3 planned for induction)

06 x UH-3H Sea King

25 x Sea King Mk-42B/C

02 x MH60R (+22 planned for induction)

14 x Kamov-31 (+ 10 planned for induction)

10 x Kamov-28

06 x Heron + 07 x Searcher UAV

02 Sea Guardian (+ 10 Sea Guardians planned for induction)

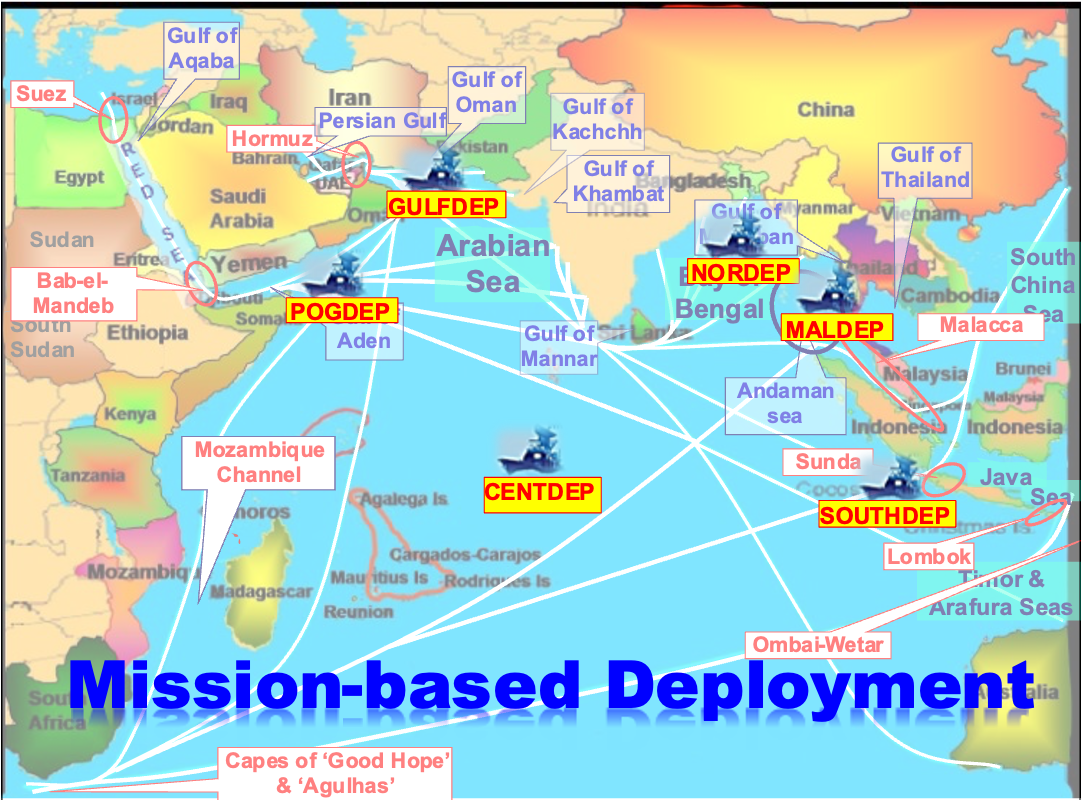

As depicted in Figure 2, The pattern of deployment of these assets is in accordance with the Navy’s mission-based deployment strategy, whereby naval forces are on continuous deployment in multiple segments of the Indian Ocean, quite apart from increasingly frequent deployments to the western and southern reaches of the Pacific Ocean.

|

Fig 2: Indian Navy: Representative Pattern of Mission-Based Deployment Source: Author |

The belief amongst far too many maritime analysts that the Indian Navy is seldom seen in the Pacific and is, therefore, only an Indian Ocean player, is not borne out by facts. In 2022, for example, the 30th edition of Exercise MALABAR was held off Japan with participation by two indigenously built Indian Naval warships, the Shivalik and the Kamorta and a P-8 (I) aircraft.[8] Farther south, the INS Satpura along with an Indian Naval P-8(I) aircraft participated in the 2022 edition of the Royal Australian Navy’s Exercise KAKADU[9] and also showcased Indian Naval presence in the port of Suva in Fiji.[10] Continuing to stamp its footprint on the Pacific segment of the Indo-Pacific, the INS Delhi, the INS Satpura and the ASW Corvette, INS Kavaratti, were extensively deployed to ASEAN countries in May and June of 2023.[11] The effectiveness of Indian naval diplomacy was evident at the Langkawi International Air and Maritime Exhibition (LIMA-2023) in May of 2023 where, despite the presence of a large number of warships from across the world, the Sultan of Kedah, His Royal Highness Al-Aminul Karim Sultan Sallehuddin ibni Almarhum Sultan Badlishah, the Prime Minister of Malaysia, Dato’ Seri Anwar Ibrahim; and the Minister of Foreign Affairs of Malaysia, Dato’ Seri Diraja Dr. Zambry Abd Kadir chose the INS Kavaratti as their ship-of-choice — the first instance of any Malaysian Prime Minister attending an onboard reception and dinner on an Indian Naval Ship.[12] In August of this year, the Indian Navy will once again demonstrate its ability to range far and wide across the Indo-Pacific when it participates in the 2023 edition of Exercise MALABAR, off Sydney, Australia.[13]

India’s impressive economic rise is a function of the country’s significant dependence upon maritime merchandise trade and the protection of all elements of this trade in the geopolitically turbulent waters of the Indo-Pacific is a task that the Indian Navy takes extremely seriously. For instance, a staggering 110 billion US dollars-worth of India’s merchandise trade (60 billion dollars-worth of exports and 50 billion dollars-worth of imports) flows through the Gulf of Aden each year. Even more significantly, a mind-boggling 190 billion US dollars-worth of India’s merchandise trade flows through the South China Sea — and this does not include India’s merchandise trade with Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore, and Thailand, all of which are Indian Ocean States! Likewise, countries and collectives located in the western Pacific are equally dependent for their economic wellbeing upon trade flows through the Gulf of Aden, around the Cape of Good Hope, and through the Strait of Hormuz. This is as true of Japan and South Korea as it is of the eleven constituent States of ASEAN. Thus, the protective abilities of the Indian Navy are vital to not just India or countries of the Indian Ocean but those of the western Pacific as well, as they struggle to mitigate and de-risk the disruptions caused to global- and regional supply- and value chains by the triad of China’s economic coercion, the Russia-Ukraine war, and the COVID-19 pandemic. Where the COVID-19 pandemic is concerned, the Indian Navy, functioning in its ‘benign’ role, has risen brilliantly to the challenge — whether it be in terms of Operation SAMUDRA SETU in May and June of 2020 involving the repatriation of Indian nationals stranded in Iran, Maldives, and Sri Lanka[14], or the five regional relief missions under the rubric of SAGAR (SAGAR-I involved the provision of medical and food supplies to Comoros, Madagascar, Maldives, and Mauritius; in November 2020, IN ships executing SAGAR-II, extended this aid to Djibouti, Eritrea, Sudan, and South Sudan; in December 2020, IN ships executed Mission SAGAR-III, providing much needed succour to Vietnam, which was reeling from widespread flooding on top of the COVID pandemic; in September of 2021, SAGAR IV saw the Indian Navy transporting COVID relief material including critical supplies of oxygen to Indonesia, Thailand and Vietnam; while in SAGAR-V the Indian Navy supplied food and medical aid to drought-hit Mozambique.[15]

The transformation of the European Union from an acknowledged normative actor into as a serious maritime-security stakeholder in the Indo-Pacific and its initiatives vis-à-vis the Coordinated Maritime Presence – North-West Indian Ocean (CMP-NWIO), and the CRIMARIO-II action that now promotes maritime domain awareness (MDA) in South and Southeast Asia, is something that the Indian Navy has welcomed wholeheartedly. The EU’s closing ranks against China’s economic coercion has provided a welcome overarch to the extremely strong cooperation between the Indian Navy and the French Navy, as typified not only by the bilateral IN-FN exercise whose 2023 edition was held off Goa in January 2023,[16] but even more emphatically by the multinational exercise LA PEROUSE in mid-March 2023, which was led by France and witnessed participation by the navies of India, Australia, Canada, the United States, France, Japan and the United Kingdom.[17] Strong strategic signalling is being effected through these exercises and the signals go across at least half the width of the Indo-Pacific, all the way to Beijing.

A few years ago, after climate science had comprehensively vanquished the Trump administration’s nay-sayers, it was widely felt that China was and would remain a valued partner in terms of both mitigation and adaptation in the face of climate change. However, this is no longer the case in 2023. Even within the EU, which was the most vocal advocate of this value, China is now perceived as an impediment to reaching the Paris climate target of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius. Beijing did not sign up to the Global Methane Pledge, which over one hundred countries signed at COP26 in Glasgow and Beijing does not, in fact, appear to be particularly interested in any climate partnerships and instead, is cynically arguing that climate cooperation is dependent upon how the West engages with China in other areas.[18] This is in sharp contrast to India, which is the only G20 country to have met its 2015 Paris climate change targets.[19] All this is, however, cold comfort in dealing with the increasingly evident maritime impacts of climate-change, especially as manifested in extreme-weather events and sea-level rise. Six major impacts that affect the mission readiness of the Indian Navy are: (1) disputes over maritime boundaries, and competition for new resources; (2) strains on naval capabilities, given increasingly complex Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief (HADR) ‘first responder’ missions across the region; (3) vulnerabilities of ports, harbours, and naval coastal installations, due to sea-level rise and increased storm surges; (4) demands for establishing more intensive and extensive international maritime partnerships to address heightened maritime demands for capacity-building and capability-enhancement by Small Island Developing States [SIDS] of the Indo-Pacific (especially the IOR), as a function of the IPCC’s climate-change scenarios; (5) impacts on the technical underpinnings that enable, in part, naval force capabilities; and (6) impacts upon submarine- and anti-submarine warfare (ASW) operations, as a result of changes in salinity levels in different coastal areas.

It may thus be seen that the Indian Navy has, as always, made the nation proud along all seven of the drivers of geopolitical change that are evident in the Indo-Pacific. It remains only for us to salute the indomitable spirit of the valiant men and women that make the Indian Navy a force that is combat ready, credible, cohesive, and future proof — one that we can truly rely upon in our collective journey through the ongoing Amrit Kaal.

*****

[1] ‘Security and Growth for all in the Region’ (SAGAR) was enunciated in 2015 by the Hon’ble Prime Minister of India, Shri Narendra Modi, in his address in Mauritius on 12 March 2015, https://pib.gov.in/newsite/printrelease.aspx?relid=116881

[2] Government of India, Ministry of External Affairs, “Prime Minister’s Keynote Address at Shangri La Dialogue”, 01 June 2018, https://www.mea.gov.in/Speeches-Statements.htm?dtl%2F29943%2FPrime_Ministers_Keynote_Address_at_Shangri_La_Dialogue_June_01_2018

[3] The SCO presently comprises eight Member States (China, India, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, Pakistan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan), four Observer States interested in acceding to full membership (Afghanistan, Belarus, Iran, and Mongolia) and nine “Dialogue Partners” (Armenia, Azerbaijan, Cambodia, Egypt, Nepal, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Sri Lanka, and Turkey).

[4] The Colombo Security Conclave (CSC), is a maritime security grouping comprising India, Sri Lanka, Mauritius, and the Maldives. Bangladesh and Seychelles are currently observers.

[5] Government of India, President’s Secretariat, “Speech by the Hon’ble President of India Shri Ram Nath Kovind on the occasion of presentation of the President’s Colour to the Submarine Arm of the Indian Navy”, 08 December 2017, Press Information Bureau Press Release, https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1512042

[6] Vice Admiral Pradeep Chauhan, “India’s Proposed Maritime Strategy”, National Maritime Foundation Website, February 3, 2020. https://maritimeindia.org/indias-proposed-maritime-strategy/

[7] Wikipedia, Indian Navy, last edited on 29 August 2023, 14:41, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indian_Navy#Equipment

[8] Government of India, Ministry of Defence, “Malabar 22 Culminates, 16 November 2022, Press Information Bureau Press Release, https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1876424

[9] Government of India, Ministry of Defence, “Indian Navy’s P8I Aircraft Participates in Exercise Kakadu”, 27 September 2022, Press Information Bureau Press Release, https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1862641

[10] Indian Navy, “INS Satpura Strengthens Friendship and Cooperation with Fiji”, 05 September 2022, Press Release, https://indiannavy.nic.in/content/ins-satpura-strengthens-friendship-and-cooperation-fiji

[11] Indian Navy, “Indian Navy’s Deployment to ASEAN Countries, INS Delhi and INS Satpura, under the Command of RAdm Gurcharan Singh, FOCEF, Arrived at Da Nang, Vietnam”, 24 May 2023, News and Updates, https://indiannavy.nic.in/content/indian-navy%E2%80%99s-deployment-asean-countries-ins-delhi-and-ins-satpura-under-command-radm

[12] High Commission of India: Kuala Lumpur, “His Royal Highness, Sultan of Kedah and PM of Malaysia participated in the onboard dinner reception at Indian Naval Ship”, Economic & Business e-Newsletter, Vol. 1 No. 6, June 2023, p-1. https://hcikl.gov.in/pdf/menu/next%20submenu_522841212.pdf

[13] Indian Navy, “Malabar-2023 at Sydney, Australia”, 11 August 2023, Press Brief, https://indiannavy.nic.in/content/malabar-2023-sydney-australia

[14] Indian Navy, “Indian Navy Completes ‘Operation Samudra Setu’”, 09 July 2020, Press Brief, https://www.indiannavy.nic.in/content/indian-navy-completes-%E2%80%9Coperation-samudra-setu%E2%80%9D

[15] Government of India, Ministry of Defence, “Mission SAGAR”, 07 February 2022, Press Information Bureau Press Release, https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1796165

[16] Government of India, Ministry of Defence, “21st Edition of India France Bilateral Naval Exercise ‘Varuna’ – 2023”, 16 January 2023, Press Information Bureau Press Release, https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1891610

[17] Indian Navy, “Exercise La Perouse – 2023”, 17 March 2023, Press Brief, https://indiannavy.nic.in/content/exercise-la-perouse-%E2%80%93-2023-1

[18] Adam Vaughan, “COP26: 105 Countries Pledge to Cut Methane Emissions by 30 per Cent.” New Scientist, 2 November 2021. https://www.newscientist.com/article/2295810-cop26-105-countries-pledge-to-cut-methane-emissions-by-30-per-cent/

[19] The White House, “Remarks by President Biden and Prime Minister Modi of the Republic of India in Joint Press Conference”, 22 June 2023, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2023/06/22/remarks-by-president-biden-and-prime-minister-modi-of-the-republic-of-india-in-joint-press-conference/

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!