Abstract: Despite its growing alignment with Pakistan, Indian strategic thinking has largely failed to accord the requisite degree of centrality to Türkiye. This article is the second in a series examining the manner in which India’s own maritime strategies within the western segment of the Indo-Pacific, namely, the Indian Ocean, are impacted by Türkiye’s maritime endeavours. It specifically explores the implications of the Pakistan–Türkiye nexus and their ongoing maritime cooperation, analysing how and to what extent this partnership affects the existing regional maritime order. This nexus manifested itself with disturbing clarity in the period following the Pahalgam terrorist attack of 22 April 2025, as also during the first four days of the India-Pakistan armed conflict in the still-ongoing Op SINDOOR, wherein Türkiye openly supported Pakistan. This article argues that this collaboration undermines not just one, but three of India’s key maritime goals, namely, (1) protection from sea-based threats to India’s territorial integrity, (2) maintaining stability in India’s maritime neighbourhood, and (3) obtaining and retaining a favourable geostrategic maritime position.

Keywords: TÜRKIYE–PAKISTAN RELATIONS, INDIA’S MARITIME STRATEGY, DEFENCE COOPERATION, NAVAL COLLABORATION, TÜRKIYE’S MARITIME ACTIVITIES, INDIA–TÜRKIYE RELATIONS, STRATEGIC ALIGNMENTS, MARITIME NEIGHBOURHOOD, REGIONAL STABILITY.

Introduction

Türkiye and Pakistan have long shared strong political, cultural, and diplomatic relations. While both India and Pakistan established ties with the Republic of Türkiye around the same period, Türkiye’s alignment has historically tilted more decisively towards Pakistan. This inclination is attributable to a combination of geopolitical, ideological, and historical factors. Although India and Türkiye enjoyed goodwill and a sense of solidarity during their respective national movements for independence, much of this affinity shifted towards Pakistan after partition— primarily due to religious and cultural affinities rooted in a shared Muslim identity. During the Cold War, this alignment deepened as both Türkiye and Pakistan joined the Western bloc through US-led alliances such as the Central Treaty Organization (CENTO), in contrast to India’s pursuit of a non-aligned foreign policy.[1] The convergence of strategic interests— particularly the goal of countering Soviet influence— was further reinforced by ideological and religious commonalities between Ankara and Islamabad.

Analyses of Türkiye–Pakistan relations are often accompanied by reflections on the trajectory of India–Türkiye ties, particularly focusing on factors that have impeded closer cooperation. Although India and Türkiye have maintained diplomatic relations since 1948, their bilateral engagement has been marked by underlying complexities.[2] While India- Türkiye ties have evolved, Türkiye’s steadfast support for Pakistan— particularly since President Erdoğan came to power— remains an enduring feature of Ankara’s foreign policy.[3] As C Raja Mohan observes, “the Turkish establishment’s uncritical embrace of Pakistan has been unchanging, irrespective of who dominated Ankara—the secular army or the current Islamist leadership.”[4]

Within this geopolitical context, this article examines the maritime dimensions of Türkiye–Pakistan relations and the broader strategic dynamics affecting the Indo-Pacific. It argues that despite historically cordial diplomatic ties, India is unlikely to rival Pakistan in Türkiye’s strategic calculus. The trust deficit between New Delhi and Ankara is expected to persist in the foreseeable future. However, this reality does not preclude India from adopting a pragmatic, interest-driven engagement strategy. By recognising and responding to the geopolitical sensitivities that underpin the Ankara–Islamabad axis, India can recalibrate its approach to regional diplomacy. Accordingly, this article traces the evolution of Türkiye–Pakistan cooperation— particularly in the maritime domain— while juxtaposing it against the broader trajectory of India–Türkiye relations. In doing so, it aims to uncover the strategic motivations behind the growing Ankara–Islamabad nexus and to offer policy-relevant insights and recommendations. These are intended to guide India in managing its relations with Türkiye in a manner that preserves and enhances its influence within its maritime neighbourhood and broader regional sphere.

Historical Backdrop: Alignments and Divergences

The foundations of Pakistan–Türkiye relations are deeply rooted in shared religious, cultural, and historical ties. Since Pakistan’s independence in 1947, these commonalities have played a pivotal role in shaping and advancing bilateral relations.[5] Türkiye was among the first countries to recognise Pakistan, appointing Yahya Kemal as its first ambassador.[6]

Türkiye’s early support for Pakistan extended beyond diplomatic formalities. It played a practical role in aiding the newly formed state by assisting with the printing of its currency and signing a Treaty of Friendship in 1954, which laid the groundwork for future defence cooperation.[7] The following year, both countries joined the Baghdad Pact— later renamed the Central Treaty Organisation (CENTO)— alongside Iran and the United Kingdom.[8] This alliance, aimed at containing Soviet influence from Europe to South Asia, represented a strategic convergence within the Western bloc.

During the Cold War, Pakistan and Türkiye aligned closely with the United States in efforts to counter the Soviet Union’s expansionist ambitions. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, the two nations collaborated on developing joint security strategies across the Middle East and South Asia. Although CENTO eventually dissolved, it had provided a lasting platform for strategic cooperation. In 1964, Pakistan, Türkiye, and Iran initiated the “Regional Cooperation for Development” (RCD), focused on socio-economic collaboration.[9] Although dissolved in 1979, the RCD was later revived as the “Economic Cooperation Organisation” (ECO) in the 1990s, expanding to include newly independent Central Asian republics (CAR).[10]

The 1970s saw further consolidation of bilateral ties amidst significant geopolitical upheavals. During the 1971 Indo-Pakistani War, Türkiye extended strong political and military support to Pakistan.[11] In return, Pakistan backed Türkiye’s 1974 military intervention in Cyprus, making it one of the few nations to offer such unequivocal support.[12] These episodes underscored how shared national security imperatives fostered deep mutual solidarity.

The 1980s marked another period of intensified cooperation, driven by shared strategic interests in countering Soviet aggression after the 1979 invasion of Afghanistan and managing the regional impact of Iran’s Islamic Revolution.[13] Under the leadership of military regimes— Zia-ul-Haq in Pakistan and Kenan Evren in Türkiye— both nations aligned with the United States and played key roles in curbing Soviet influence and advancing Western-aligned stability in the region.[14]

The 1990s, however, witnessed a relative cooling of bilateral ties. Although political engagement remained consistent, economic cooperation stagnated. Türkiye shifted its foreign policy priorities toward Central Asia and the Balkans, while Pakistan became deeply involved in Afghanistan, notably supporting the Taliban.[15] Conversely, Türkiye favoured the opposing Northern Alliance, leading to a divergence in their Afghanistan policies.

The early 2000s ushered-in a renewed phase of collaboration, particularly in the context of post-2001 efforts to stabilise Afghanistan following NATO’s intervention. Türkiye took on a mediating role between Afghanistan and Pakistan and also worked to support Pakistan’s internal stability.[16] Pakistan and Türkiye have continued to align on major global Islamic issues. Both countries have consistently voiced support for the Palestinian cause and taken proactive stances against the rise of Islamophobia. Their shared vision of forming a unified Islamic bloc reflects broader aspirations for leadership within the Muslim world. In recent years, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has deepened Türkiye’s engagement with Pakistan, partly driven by his ambition to position himself as a leader of the Muslim Ummah.[17] His vocal advocacy for the Kashmir cause and condemnation of violence against Indian Muslims have resonated strongly in Pakistan.[18] Erdoğan’s consistent support for Pakistan’s stance on Kashmir has been warmly received by both Pakistani officials and separatist leaders in the region.

These ideological alignments have also solidified the trilateral nexus between Pakistan, Türkiye, and Azerbaijan. Pakistan remains the only country in the world that does not recognise Armenia and has staunchly supported Azerbaijan’s claims over Nagorno-Karabakh.[19] This strategic alliance has significant geopolitical implications: Armenia supports India’s stance on Kashmir, while Azerbaijan aligns with Pakistan.[20] These reciprocal relationships underscore how contested territorial issues continue to shape regional alliances.

Amid heightened India–Pakistan tensions in 2025, Türkiye has once again demonstrated unequivocal support for Pakistan, including providing military assistance under the banner of goodwill.[21] By refraining from criticising Pakistan’s alleged links to terrorism and consistently backing Islamabad in international forums, Ankara has made a calculated decision. Türkiye’s actions and sustained support for Pakistan—particularly during periods of heightened tension and ensuing armed conflict such as the recent Op SINDOOR— have seriously jeopardised its diplomatic relations with New Delhi, highlighting the deliberate strategic choice Ankara has made to prioritise ideological alignment and geopolitical partnership with Islamabad.

Defence Diplomacy in Action

Defence diplomacy has emerged as one of the most robust pillars of the Pakistan–Türkiye bilateral relationship, with foundations stretching back to the early Cold War era. The 1954 Treaty of Friendship laid the groundwork for formal military cooperation, enabling joint efforts in training, military education, and the development of defence capabilities.[22] This framework was further institutionalised through the establishment of the Pakistan–Türkiye Military Consultative Group (MCG) in 1988 and the High-Level Military Dialogue Group (HLMDG) in 2003—mechanisms that continue to facilitate strategic coordination.[23]

Since the early 2000s, strategic convergence between Ankara and Islamabad has deepened, driven by shared regional security interests and expanding defence industrial capacities. Combined military exercises such as ANATOLIAN EAGLE and INDUS VIPER have become recurring engagements aimed at enhancing interoperability between their armed forces.[24] In February 2025, Pakistan and Türkiye concluded the combined military exercise ATATURK-XIII, further reinforcing operational synergy and defence ties.[25] This synergy was in stark evidence during Op SINDOOR.

In May 2025, Pakistan launched a large-scale drone offensive along India’s western border, deploying 300–400 Turkish-manufactured drones—including Asisguard Songar and Bayraktar TB2 models—across multiple Indian territories.[26] The unprecedented nature of the attack highlighted Pakistan’s growing reliance on Turkish military platforms, as well as the operational presence of Turkish advisors within the Pakistani defence establishment. India’s retaliatory campaign, Op SINDOOR, allegedly resulted in the elimination of two Turkish operatives, underscoring Ankara’s covert involvement in the conflict.[27] Meanwhile, the Turkish Navy’s TCG Büyükada made a port call in Karachi amid ongoing hostilities, reinforcing perceptions of strategic alignment between the two militaries.[28] However, the high failure rate of Turkish drones during the offensive has raised serious questions about their operational credibility, becoming a subject of scrutiny in emerging assessments of Türkiye’s drone diplomacy.[29]

Industrial cooperation in defence, too, has witnessed exponential growth. As of 2023, it was Pakistan’s second-largest arms supplier, accounting for 11% of the country’s total defence imports.[30] Pakistan’s acquisition of four MILGEM Class corvettes from Türkiye and the 2018 agreement for 30 T129 ATAK helicopters exemplify high-value transactions.[31] Although the helicopter deliveries faced delays due to the US sanctions and export licence restrictions related to the CTS800 engine, Türkiye’s Tusas Engine Industries (TEI) has been tasked with developing an indigenous alternative, underscoring Ankara’s resolve to maintain strategic autonomy and honour its defence commitments. Islamabad has responded with flexibility, extending delivery timelines— a clear indication of political trust and mutual confidence. Türkiye has also contributed to the modernisation of Pakistan’s naval capabilities, notably through STM’s upgrade of two Agosta 90B submarines, with a third project underway, further details of which are discussed in the section on maritime cooperation.

Importantly, Pakistan is not merely a recipient but also a contributor to Türkiye’s defence sector. In 2017, a contract for 52 Super Mushshak trainer aircraft was signed with the Pakistan Aeronautical Complex (PAC), marking a rare instance of Pakistani defence exports to a NATO member.[32] Although the COVID-19 pandemic caused delays, deliveries resumed by late 2022, reaffirming the reciprocal nature of the defence relationship.

Technological collaboration, too, has expanded. Pakistan has acquired Turkish-made TB2 and Akıncı drones[33] and has expressed interest in participating in Türkiye’s fifth-generation fighter jet programme, KAAN.[34] This reflects a shared ambition to co-develop advanced platforms and solidifies the deepening of strategic defence cooperation.

Further institutional strengthening occurred during the 6th and 7th sessions of the High-Level Strategic Cooperation Council (HLSCC). Both nations pledged to enhance collaboration in research and development, co-production, cybersecurity, and counterterrorism. The 7th session, co-chaired by President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif in Islamabad, resulted in the signing of 24 agreements and memoranda of understanding (MoUs), covering defence, energy, mining, and broader economic cooperation.[35]

In sum, the Pakistan–Türkiye defence partnership has evolved from symbolic Cold War-era alignment into a comprehensive, multidimensional strategic alliance. It is underpinned by institutional mechanisms, mutual defence production, and shared technological aspirations. This deepening relationship reflects not only enduring bilateral trust but also a broader vision of regional autonomy and geopolitical convergence in an increasingly multipolar world.

Türkiye-Pakistan Maritime Cooperation

Türkiye has been steadily deepening its maritime cooperation with Pakistan for more than two decades, framing this engagement as part of its broader strategy to cultivate strategic relationships with Muslim-majority states. Naval collaboration has become one of the most visible aspects of this trajectory, reflecting the convergence of Ankara and Islamabad’s security interests and shared geopolitical outlooks. This partnership has evolved through a combination of defence procurement, joint exercises, training programmes, and naval industrial collaboration.[36]

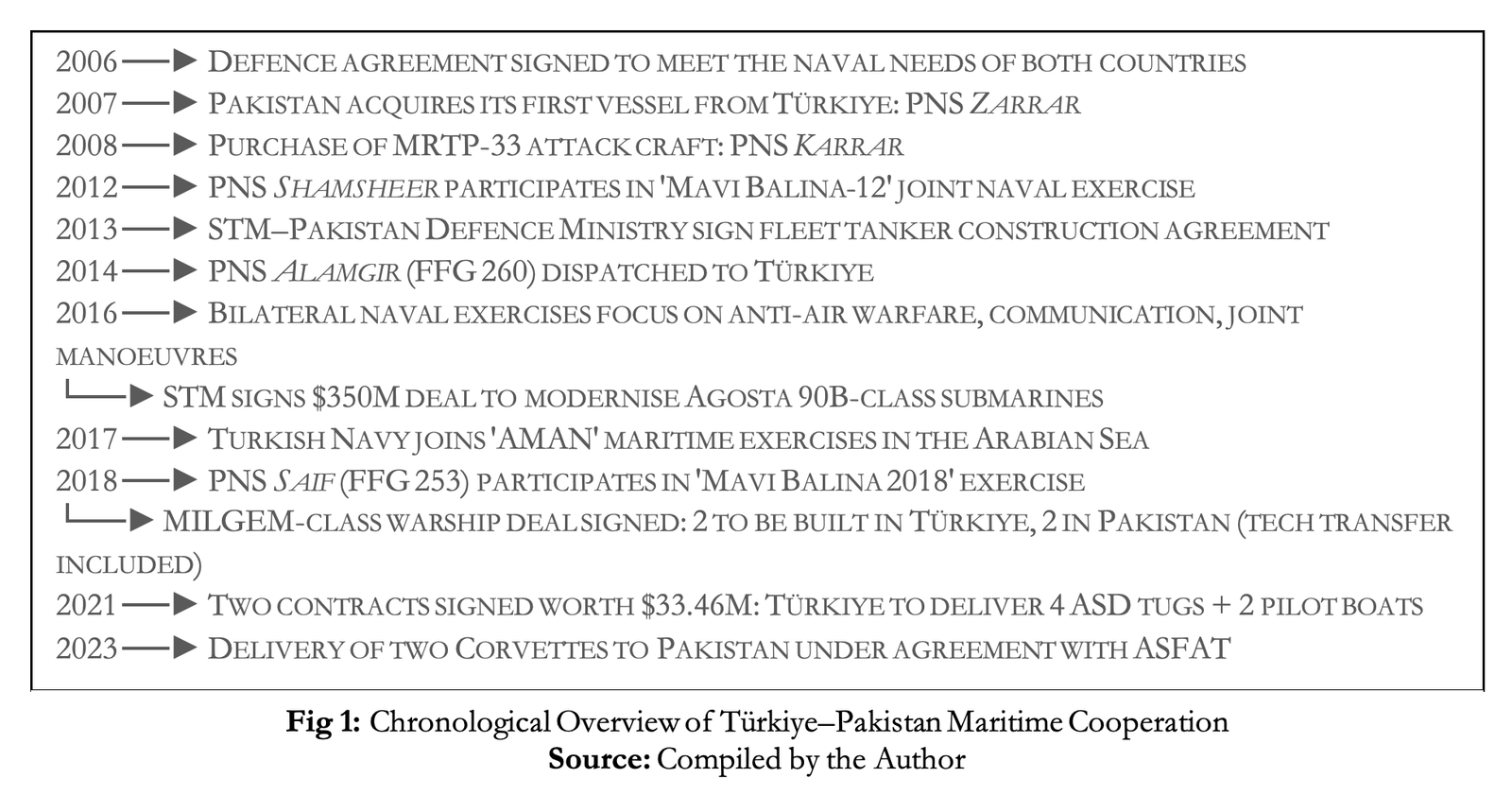

The foundation for sustained cooperation was laid in 2006 with a bilateral agreement aimed at meeting the naval defence needs of both countries.[37] This paved the way for a series of acquisitions by Pakistan from Turkish suppliers. In 2007, Islamabad procured the PNS Zarrar, followed by the PNS Karrar—an MRTP-33 fast attack craft—in 2008.[38] These early transfers signalled Pakistan’s interest in diversifying its defence partnerships, while Türkiye positioned itself as a reliable partner in maritime modernisation. Joint naval exercises soon became a regular feature of bilateral ties. The participation of PNS Shamsheer in Türkiye’s 2012 MAVI BALINA (Blue Whale) anti-submarine warfare exercise exemplified the growing operational alignment between the two navies.[39] These exercises not only enhanced interoperability but also symbolised the common ambition of both States to operate as regional providers of maritime security. Subsequent deployments— such as the dispatch of PNS Alamgir in 2014 and bilateral drills in 2016 focusing on anti-air warfare and joint manoeuvres— reinforced this trend.[40]

Since 2017, Türkiye has participated in multilateral initiatives led by Pakistan, notably the AMAN (Peace) series of naval exercises in the Arabian Sea, wherein Turkish naval presence has been welcomed as a contribution to regional maritime stability.[41] The 2018 edition of the MAVI BALINA exercise saw active Pakistani participation, with PNS Saif playing a prominent role.[42] These interactions serve a dual purpose: enhancing professional naval cooperation and showcasing the symbolic alignment of both countries in their approach to maritime security.

Beyond exercises, Türkiye’s defence industry has played an instrumental role in upgrading Pakistan’s naval infrastructure. A 2013 agreement between STM (Savunma Teknolojileri Mühendislik ve Ticaret A.Ş.) and Pakistan’s Ministry of Defence led to the construction of a fleet tanker incorporating Turkish design, technology, and armaments.[43] STM is a Turkish company that provides project management, systems engineering, technology transfer, technical and logistical support, and consultancy services to the Presidency of the Republic of Türkiye’s Presidency of Defence Industries (SSB) and the Turkish Armed Forces (TSK) in areas requiring high technology for national security.[44] The vessel’s logistical and operational capacities were intended to enhance Pakistan’s blue-water naval aspirations. In 2016, a further US$350 million contract was awarded to STM to modernise the Agosta 90B-class submarines, previously developed by France.[45] This marked a strategic shift in Pakistan’s procurement preferences and highlighted Ankara’s growing credibility in delivering advanced maritime platforms.

The most ambitious collaboration to date has been the MILGEM-class corvette programme, signed in 2018. Under this agreement, Türkiye’s ASFAT (Military Factory and Shipyard Management Corporation) committed to co-producing four corvettes for the Pakistan Navy, with two being built in Türkiye and two at the Karachi Shipyard, alongside a comprehensive technology-transfer arrangement.[46] These ships, equipped with modern sensor suites and weapons systems, are optimised for multi-domain operations and reflect a shift toward more sophisticated defence co-production models. The launch of the first corvette, PNS Babur, in Istanbul in 2021, followed by the launch of PNS Badr in Karachi in 2022, symbolised the strategic nature of this partnership.[47] Two corvettes have already been delivered under the project, and the remaining vessels— PNS Khaibar, launched in November 2022 in Istanbul, and PNS Tariq, the fourth and final corvette, launched at Karachi Shipyard in August 2023— are expected to be completed by 2025.[48] Complementing these efforts, Türkiye has also supplied smaller auxiliary vessels, including ASD tugs and pilot boats, under a $33 million agreement in 2021 with Pakistan’s Port Qasim Authority.[49] These platforms enhance operational readiness and port security— particularly significant given Pakistan’s increasing focus on securing its maritime zones in the face of regional tensions.

Figure 1 depicts the key milestones outlined above in chronological order, highlighting the progression of Türkiye–Pakistan maritime cooperation since 2006.

Figure 1 depicts the key milestones outlined above in chronological order, highlighting the progression of Türkiye–Pakistan maritime cooperation since 2006.

Overall, Türkiye’s maritime engagement with Pakistan reflects a broader strategic calculus that blends ideological affinity with pragmatic defence cooperation. For Islamabad, Ankara offers a dependable partner capable of delivering advanced naval platforms and training without the political constraints associated with Western suppliers. For Türkiye, the relationship with Pakistan serves as a gateway to the Arabian Sea and a demonstration of its expanding role as a maritime-industrial actor in the broader Muslim world. As this cooperation deepens, it signals a growing alignment between two key regional powers seeking to enhance their strategic autonomy and maritime influence.[50]

Impacts, Challenges, and Structural Hurdles

Despite their multidimensional engagements, economic cooperation remains the weakest link in the Pakistan–Türkiye bilateral relationship. This persistent shortfall has been a matter of concern for policymakers and economists in Pakistan, as Pakistan does not feature in Türkiye’s list of top ten trading partners, nor does Türkiye appear in Pakistan’s.[51] The situation is particularly stark when compared to Türkiye’s trade with India: despite their frequently strained political relations, bilateral trade between Türkiye and India surpassed US$10.7 bn in 2021-22.[52] In contrast, Pakistan–Türkiye trade, even at an all-time high, only reached US$1.4 billion in 2024.[53]

There have been continuous efforts to unlock the economic potential of this partnership, including trade agreements and, more recently, a move toward shared dual citizenship.[54] A significant development in this direction was the signing of a Preferential Trade Agreement (PTA) between the two countries in May 2023.[55] The PTA entails tariff liberalisation on 130 tariff lines by Pakistan and 261 by Türkiye.[56] However, many economists remain sceptical of the agreement’s long-term impact, viewing it as overly ambitious in the short term and limited in scope.

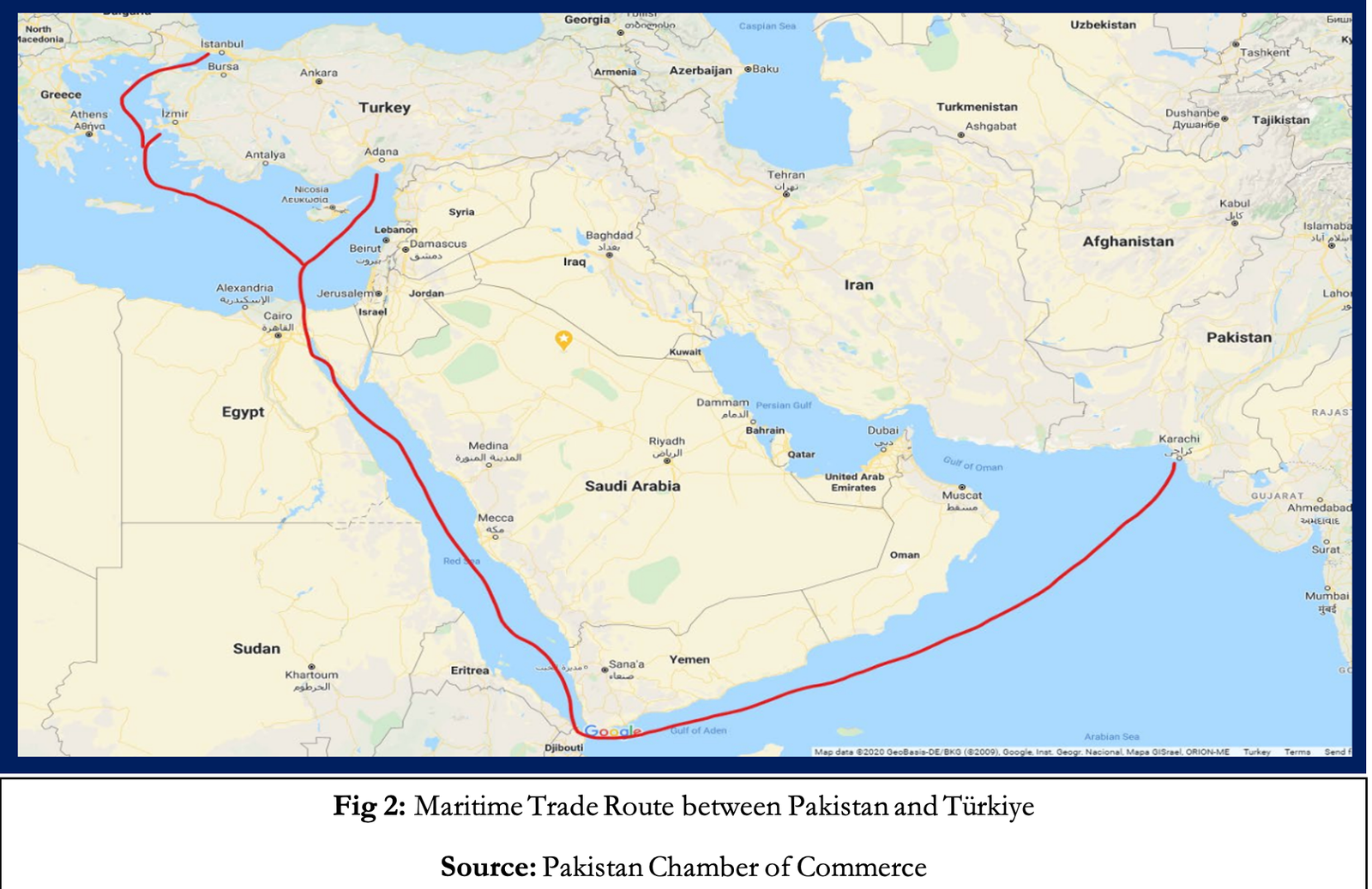

A major structural impediment to enhancing trade is the absence of a direct shipping and logistical route between the two countries.[57] As shown in Figure 2, maritime trade currently requires goods to transit through two critical chokepoints— the Suez Canal and the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait— rendering it highly susceptible to broader geopolitical disruptions. This lack of logistical connectivity, combined with underdeveloped economic ties, continues to constrain the emergence of a more durable and strategic political alliance between Pakistan and Türkiye.

Additionally, the ideological dimension of Türkiye’s partnership with Pakistan should not be overlooked. By consistently supporting Pakistan’s position on the Kashmir dispute and advocating for the Palestinian cause, Türkiye appears to be positioning itself as a leader of an alternative bloc within the Muslim world— one that challenges the traditional dominance of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.[58] This ambition was evident during the 2019 Kuala Lumpur Summit, jointly conceived by Türkiye, Pakistan, and Malaysia, which was notably boycotted by Saudi Arabia and several other prominent member states of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC).[59] These developments, combined with Türkiye’s growing alignment with Pakistan and Malaysia, suggest the potential formation of a Türkiye–Pakistan–Malaysia axis. However, for Pakistan, closer alignment with this emerging bloc requires cautious diplomacy to maintain its strategic and economic ties with Saudi Arabia and the broader Gulf region[60]. This balancing act becomes even more significant as India continues to deepen its relations with key Arab states, including Saudi Arabia and the UAE. India may seek to leverage Türkiye’s strained relations with these countries to bolster its own geopolitical standing in the region.

Way Forward: Recommendations for India

- In light of the strategic implications posed by the expanding Türkiye–Pakistan defence nexus— especially its alignment with China— India must adopt a balanced yet proactive policy.

- Pragmatic engagement with Türkiye needs to be prioritised, focusing on selective cooperation in trade and multilateral platforms while firmly delineating red lines on Pakistan-related sensitivities.

- To counter Türkiye’s growing regional footprint, India should deepen its strategic and defence ties with Gulf states such as the UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt, which hold diverging interests from Ankara.

- Maritime security must also be reinforced through intensified naval cooperation with Indian Ocean littoral states and enhanced engagement with NATO navies to monitor Türkiye–Pakistan collaboration in the Arabian Sea.

- Simultaneously, to prevent further escalation of diplomatic friction, India needs to revitalise its soft power strategy by promoting cultural diplomacy and civilisational linkages with Türkiye.

- Given Türkiye’s overt support for Pakistan and the currently severed or limited bilateral ties, the government should institutionalise Track-II dialogue mechanisms— such as the one held in February 2025, the International Conference on India-Türkiye Relations: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives, organised by SETA and IDDF India in partnership with the Embassy of India in Ankara[61]— to engage Turkish think tanks, academia, and business communities. This approach would allow India to maintain influence over elite opinion, gain insight into Türkiye’s strategic thinking, and avoid being sidelined, thereby preventing Ankara from freely strengthening a hostile nexus in a space created by India’s absence.

Conclusion

The deepening strategic and maritime cooperation between Türkiye and Pakistan poses multidimensional challenges to India’s core maritime goals: safeguarding territorial integrity from sea-based threats, maintaining regional maritime stability, and securing a favourable geostrategic position in the Indian Ocean Region. Their growing naval exercises, submarine collaborations, and joint defence production not only enhance Pakistan’s maritime capabilities but also symbolise a broader realignment that could tilt the balance of power in the Arabian Sea. For India, this evolving axis necessitates both vigilance and strategic adaptation.

Encouragingly, India is already moving to recalibrate its posture. By strengthening defence and diplomatic ties with Türkiye’s traditional rivals— such as Greece and Cyprus— India is expanding its presence in the Eastern Mediterranean. Moreover, India’s emergence as Armenia’s top arms supplier, a development that has unsettled both Ankara and Islamabad, signals a more assertive and targeted form of defence diplomacy.[62] This multidirectional engagement reflects India’s shift from a reactive to a proactive maritime strategy. To sustain this momentum, India must continue leveraging strategic partnerships, invest in naval diplomacy, and ensure that its maritime neighbourhood remains stable, rules-based, and favourable to its long-term interests.

******

About the Author

Ms Aditi Thakur is a Research Associate at the National Maritime Foundation. She holds a master’s degree in political science from the Centre for Political Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. Her research primarily focuses upon the manner in which India’s own maritime geostrategies in the Indo-Pacific are impacted by those of Russia and Türkiye. She may be contacted at irms3.nmf@gmail.com.

Endnotes:

[1] Gloria Shkurti Özdemir and Rizwan Zeb, “Dynamics of Pakistan-Türkiye Relations in a Challenging Global Order,” Strategic Studies 44, No 1 (Summer 2024): 64–88. https://issi.org.pk/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/4-Gloria_Shkurti_Ozdemir_and_Rizwan_Zeb__No_1_2024.pdf

[2] Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, India–Türkiye Relations, 19 August 2023. https://www.mea.gov.in/Portal/ForeignRelation/19_-08-_2023_Websits_India_-_Turkiye_Relations__1_.pdf

[3] Muhammad Ahmad and Zoonia Naseeb, “Pakistan Turkey Economic and Strategic Relations under Erdogan’s Administration,” Journal of Development and Social Sciences 4, No 3 (July–September 2023). https://ojs.jdss.org.pk/journal/article/view/692

[4] Ahmad and Naseeb, “Pakistan Turkey Economic and Strategic Relations.”

[5] Republic of Türkiye, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Türkiye–Pakistan Relations,” last modified 2024. https://www.mfa.gov.tr/turkiye-pakistan-relations.en.mfa

[6] Shkurti Özdemir and Zeb, “Dynamics of Pakistan-Turkey Relations,” 64.

[7] Shkurti Özdemir and Zeb, “Dynamics of Pakistan-Turkey Relations,” 64.

[8] Shkurti Özdemir and Zeb, “Dynamics of Pakistan-Turkey Relations,” 64.

[9] Kiran Nayyar, Muhammad Salim, and Syeda Afshan Aziz, “Pak-Turk Relations: Through the Spectrum of Regional Integration,” Pakistan Journal of International Affairs 5, No 2 (2022): 34–52. https://pjia.com.pk/index.php/pjia/article/view/537

[10] Nayyar, Salim, and Aziz, “Pak-Turk Relations,” 2022.

[11] Nayyar, Salim, and Aziz, “Pak-Turk Relations,” 2022.

[12] Islamuddin Sajid, “Pakistan Extends ‘Unwavering’ Support to Türkiye on Cyprus Issue,” Anadolu Agency, 13 February 2025. https://www.aa.com.tr/en/asia-pacific/pakistan-extends-unwavering-support-to-turkiye-on-cyprus-issue/3480904

[13] Nayyar, Salim, and Aziz, “Pak-Turk Relations,” 2022.

[14] Nayyar, Salim, and Aziz, “Pak-Turk Relations,” 2022.

[15] Nayyar, Salim, and Aziz, “Pak-Turk Relations,” 2022.

[16] Timor Sharan and Andrew Watkins, Mediator in the Making? Türkiye’s Role and Potential in Afghanistan’s Peace Process (Kabul: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Afghanistan, 2021). https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/kabul/17526.pdf

[17] Ahmad and Naseeb, “Pakistan Turkey Economic and Strategic Relations.”

[18] “President Erdogan Trends on Twitter After UN Speech,” TRT World, 24 September 2019. https://www.trtworld.com/Türkiye/president-erdogan-trends-on-twitter-after-un-speech-30092.

[19] Ayaz Ahmed, “Why Is Pakistan the Only Country That Does Not Recognise Armenia?” The Express Tribune, 16 October 2020. https://tribune.com.pk/article/97102/why-is-pakistan-the-only-country-that-does-not-recognise-armenia

[20] Ahmad and Naseeb, “Pakistan Turkey Economic and Strategic Relations.”

[21] FP Explainers, “Explained: Why Turkey Is Cosying Up to Pakistan and Targeting India,” Firstpost, 5 April 2024. https://www.firstpost.com/explainers/Türkiye-pakistan-strategic-alliance-history-india-operation-sindoor-13887305.html

[22] Selçuk Çolakoğlu, “Türkiye-Pakistan Security Relations since the 1950s,” Middle East Institute, 25 November 2013. https://www.mei.edu/publications/Türkiye-pakistan-security-relations-1950s

[23] Pakistan Ministry of Defence, Annual Report 2004–05 (Islamabad: MoD, 2005), 17. https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/15025/Pakistanyb0405.pdf

[24] “Pak-Turkey Air Exercise Concludes,” Turkish News, 18 March 2013. https://www.turkishnews.com/en/content/2013/03/18/pak-turkey-air-exercise-concludes/

[25] “Pakistan, Türkiye Conclude Joint Military Exercise ‘Ataturk-XIII’ to Bolster Defense Ties,” Arab News, 20 February 2025. https://www.arabnews.com/node/2590945/pakistan

[26] PIB India, “Press Briefing on Operation Sindoor,” YouTube video, 21:30, 9 May 2025. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sAEKInbDqDc

[27] “Turkey’s Role in India‑Pakistan Conflict Exposed: Two Military Operatives Killed in Operation Sindoor,” Indian Defence Research Wing, 14 May 2025. https://idrw.org/turkeys-role-in-india-pakistan-conflict-exposed-two-military-operatives-killed-in-operation-sindoor/

[28] “Turkish Warship Docks in Karachi: Ankara-Islamabad Tighten Military Axis Amid India-Pakistan Standoff,” Defence Security Asia, 2 May 2025. https://defencesecurityasia.com/en/turkish-warship-docks-in-karachi-ankara-islamabad-tighten-military-axis-amid-india-pakistan-standoff/

[29] Michael Rubin, “Is Turkey’s Arms Industry a Loser in the India‑Pakistan War?” American Enterprise Institute, 19 May 2025. https://www.aei.org/op-eds/is-turkeys-arms-industry-a-loser-in-the-india-pakistan-war/

[30] Pieter D Wezeman et al, “Trends in International Arms Transfers, 2023,” SIPRI Fact Sheet (Solna: Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, March 2024). https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2024-03/fs_2403_at_2023.pdf

[31] İbrahim Sünnetçi, “T129 ATAK Helicopters and ADA Class Corvettes Sale to Pakistan,” Defence Türkiye Magazine, Issue 84, August 2018. https://www.defenceTürkiye.com/en/content/t129-atak-helicopters-and-ada-class-corvettes-sale-to-pakistan-3121

[32] “Türkiye to Purchase 52 Super Mushshak Aircraft from Pakistan,” Defence Türkiye Magazine, Issue 72, March 2017. https://www.defenceTürkiye.com/en/content/Türkiye-to-purchase-52-super-mushshak-aircraft-from-pakistan-2532

[33] “Pakistan Acquires Cutting-Edge Turkish Bayraktar Akinci Drones; India Concerned,” IMR Media, 19 April 2023. https://imrmedia.in/pakistan-acquires-cutting-edge-turkish-bayraktar-akinci-drones-india-concerned/

[34] “Turkiye, Pakistan to Establish Joint Factory for Production of KAAN Fighter Jet,” Middle East Monitor, 22 January 2025. https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20250122-turkiye-pakistan-to-establish-joint-factory-for-production-of-kaan-fighter-jet/

[35] Zeynep Rakipoglu, Irem Demir, and Gizem Nisa Cebi, “Türkiye, Pakistan Sign 24 Cooperation Agreements to Strengthen Bilateral Ties,” Anadolu Agency, 13 February 2025. https://www.aa.com.tr/en/asia-pacific/turkiye-pakistan-sign-24-cooperation-agreements-to-strengthen-bilateral-ties/3481013

[36] Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Pakistan, Pakistan–Türkiye Bilateral Relations Overview. https://mofa.gov.pk/pakistan-Türkiye-relations/

[37] Rizwan Shah and Xiaolin Ma, “Maritime Dimensions of Pakistan–Turkey Strategic Partnership: Geopolitical Implications for the Indo-Pacific,” Australian Journal of Maritime & Ocean Affairs 16, No 1 (2024): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/18366503.2024.2343194

[38] Shah and Ma, “Maritime Dimensions of Pakistan–Turkey Strategic Partnership”, 6.

[39] Shah and Ma, “Maritime Dimensions of Pakistan–Turkey Strategic Partnership”, 7.

[40] Shah and Ma, “Maritime Dimensions of Pakistan–Turkey Strategic Partnership”, 7.

[41] Ankit Panda, “Pakistan Kicks Off Large Multinational Naval Exercise,” The Diplomat, 13 February 2017. https://thediplomat.com/2017/02/pakistan-kicks-off-large-multinational-naval-exercise/

[42] “Pakistan Navy Ship SAIF’s Participation in Mavi Balina 2018,” Trade Chronicle, 26 October 2018. https://tradechronicle.com/pakistan-navy-ship-saifs-participation-in-mavi-balina-2018/

[43] STM, “Pakistan Navy Fleet Tanker Project,” last accessed 29 May 2025. https://www.stm.com.tr/en/our-solutions/naval-engineering/pakistan-navy-fleet-tanker-project

[44] STM Defence, “About Us,” last accessed 30 May 2025. https://www.stm.com.tr/en/who-we-are/about-us

[45] “STM to Modernize Khalid-class Agosta 90B Submarines of the Pakistan Navy,” Army Recognition, 25 June 2016. https://armyrecognition.com/archives/archives-naval-defense/naval-defense-2016/stm-to-modernize-khalid-class-agosta-90b-submarines-of-the-pakistan-navy

[46] “A Look at PN MILGEM/JINNAH Program,” Defence Turkey Magazine, January 2021, https://www.defenceTürkiye.com/en/content/a-look-at-pn-milgem-jinnah-program-4338

[47] Sana Jamal, “Pakistan Navy Launches PNS Tariq – the Final Warship under MILGEM Project,” Gulf News, 3 August 2023. https://gulfnews.com/world/asia/pakistan/pakistan-navy-launches-pns-tariq—the-final-warship-under-milgem-project-1.97343415

[48] Jamal, “Pakistan Navy Launches PNS Tariq.”

[49] Middle East Monitor, “Türkiye, Pakistan Sign Shipbuilding Pact,” 30 March 2021. https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20210330-Türkiye-pakistan-sign-ship-manufacturing-pact/

[50] Shazia Hasan, “Pakistan, Turkiye Must Augment Strategic Ties: PM,” Dawn, 3 August 2023. https://www.dawn.com/news/1768090

[51] World Bank, “Pakistan Trade Balance, Exports and Imports by Country,” World Integrated Trade Solution (WITS), 2022. https://wits.worldbank.org/CountryProfile/en/Country/PAK/Year/2022/TradeFlow/EXPIMP/Partner/by-country.

[52] Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, India–Türkiye Relations, Central Europe Division, 19 August 2023. https://www.mea.gov.in/Portal/ForeignRelation/19_-08-_2023_Websits_India_-_Turkiye_Relations__1_.pdf

[53] Seda Sevencan and Mucahithan Avcioglu, “Türkiye’s Bilateral Trade with Pakistan Reached Historical High in 2024, Says President Erdogan,” Anadolu Agency, 13 February 2025. https://www.aa.com.tr/en/asia-pacific/turkiyes-bilateral-trade-with-pakistan-reached-historical-high-in-2024-says-president-erdogan/3481175

[54] Gulf News Report, “New Citizenship Law: Pakistan Expands Dual Nationality to 22 Additional Countries,” Gulf News, 26 April 2025. https://gulfnews.com/world/asia/pakistan/new-citizenship-law-pakistan-expands-dual-nationality-to-22-additional-countries-1.500107051

[55] Pakistan Business Council, “The Road Ahead: Opportunities in a Turkey-Pakistan Free Trade Agreement,” Market Access Series 2024–25, Karachi: Pakistan Business Council, 2024. https://www.pbc.org.pk/research/the-road-ahead-opportunities-in-a-turkiye-pakistan-free-trade-agreement/

[56] Pakistan Business Council, The Road Ahead, 2024.

[57] Bilal Khan Pasha, Pakistan–Turkey Trade Relations, presentation, Federation of Pakistan Chambers of Commerce & Industry (FPCCI), September 2022, https://fpcci.org.pk/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Pak-Türkiye-Bilateral-Trade.pdf

[58] Vinay Kaura, “The Erdogan Effect: Turkey’s Relations with Pakistan and India,” Institute of South Asian Studies, National University of Singapore, 16 October 2020. https://www.isas.nus.edu.sg/papers/the-erdogan-effect-Türkiyes-relations-with-pakistan-and-india/

[59] Prashant Waikar and Mohamed Nawab Mohamed Osman, “The 2019 Kuala Lumpur Summit: A Strategic Realignment in the Muslim World?” Berkley Center for Religion, Peace & World Affairs, 24 February 2020. https://berkleycenter.georgetown.edu/posts/the-2019-kuala-lumpur-summit-a-strategic-realignment-in-the-muslim-world

[60] Kaura, The Erdogan Effect.

[61] SETA Foundation, “International Conference: Türkiye-India Relations: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives,” 22 February 2025. https://www.setav.org/en/international-conference-turkiye-india-relations-historical-and-contemporary-perspectives/

[62] Syed Fazl-e-Haider, “India Becomes Armenia’s Largest Defense Supplier,” Eurasia Daily Monitor, Vol 21, No 131, 12 September 2024. https://jamestown.org/program/india-becomes-armenias-largest-defense-supplier/

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!