Abstract

The Indo-Pacific Region is presently beset with many maritime security problems, both, traditional as well as non-traditional. While traditional problems can only be solved by the States directly concerned; the broad spectrum of non-traditional challenges adversely affect all States in some ways or the other. Most States are hard pressed to develop their maritime capabilities to a level wherein they can address such threats on their own. The trans-national nature of such threats arising at-, from-, or through the vast seas creates additional complexities and consequent burden on national resources. It is therefore well neigh impossible for a single State to effectively respond to all these challenges. This article, while advocating the use of the term ‘Indo-Pacific’ in preference to ‘Asia-Pacific’ — so as to highlight the salience of Indian Ocean part of Asia in popular imagination — argues that there is great merit in collaborative engagement of all affected parties to synergise their efforts. Towards this, the raising of a ‘50-60 ship collective force’ as the first line of response strategy has been recommended. While it may take some time to get this endeavour off the ground, a case has been made out for more countries to join the relatively easy construct of IPOI, in the interim.

Keywords: 1000-Ship Navy, ADMM-Plus, Asia-Pacific, Drug Running, Indo-Pacific, IPOI, IUU Fishing, Paracels, Seven Pillars, Spratlys, Strategic Geography

The Indo-Pacific region forms about two-third of the Earth’s surface and comprises equivalent share of ocean extent, global population, resources and GDP. Alongside these factors, the Indo-Pacific is also home to commensurate number of geopolitical contestations, simmering tensions, underlaying fault lines and consequent potential for conflict and instability.

However, before elucidating on the core dynamics which contribute to a largely unstable environment in the region, and the challenges of military capability development to address or at least mitigate risk factors therein; it would be prudent to point out the nuanced difference between the terms ‘Indo-Pacific’ and ‘Asia-Pacific’. These terms often tend to be used interchangeably, either intentionally or inadvertently. The aim of the exercise is, of course, to bring the much-desired focus of the global strategic community on the Indian ocean littorals of Asia; as opposed to the conceptualisation of the ‘Asia-Pacific’ region, which connotes the dominance of East Asian and North Pacific countries therein. Consequently, the Indian sub-continent, and indeed the entire sub-region extending up to the eastern shores of Africa, gets pushed to the periphery — both spatially and cognitively. The resultant effect is that the problems, interests, and indeed every aspect of human and economic development in the Indian Ocean side of Asia-Pacific region gets relegated to the fringes.

On the other hand, the term ‘Indo-Pacific’ places this Indian ocean sub-region on par with the Pacific Ocean littoral. This in turn, helps in gauging the entire region holistically in terms of the interests and challenges lying therein. It is thus important for the ‘World at large’ to preferably use the term ‘Indo-Pacific’, so that the Indian sub-continent and its geo-strategic dynamics receive the required salience, whenever and in whatever context, the region is referred to.

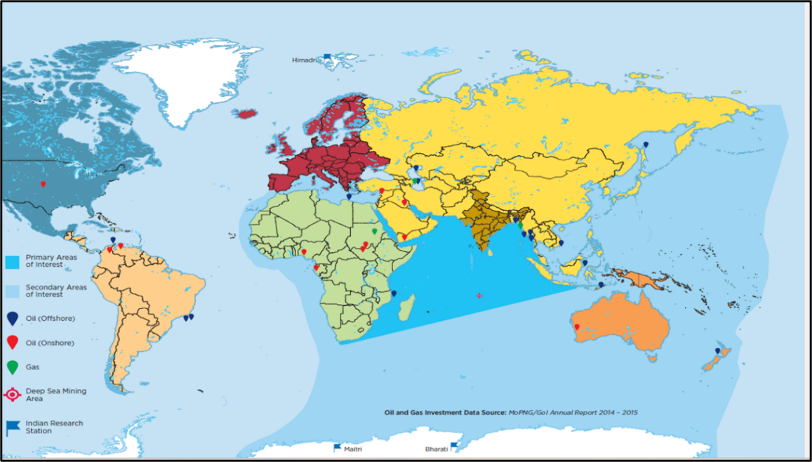

Now that the rationale for using the term ‘Indo-Pacific’ instead of the ‘Asia-Pacific’ has been presented, it would be in the fitness of things to argue that while the ‘Indo-Pacific’ may just be a theoretical concept for the global community; it is the ‘strategic geography’ of India, within which the country seeks to accord full play to its maritime security objectives.[1] India’s areas of maritime interest — both, primary and secondary — occupy substantial sea-space within this strategic geography, as apparent from the map shown in Figure 1. While the primary areas generally lie in the Indian Ocean, where India’s trade and energy sea lines of communications (SLOCs) as well as critical choke points are located; the secondary areas of interest extend well into the mid-Pacific Ocean, right up to the Russian tip of Sakhalin off the Bering Strait.[2]

Figure 1: India’s primary and secondary areas of maritime interests

Source: Indian Maritime Security Strategy-2015

Security Challenges in the Indo-Pacific Region

The ‘Indo-Pacific’ region faces many traditional and non-traditional challenges some pre-existing, and others of evolutionary nature. Traditional challenges span the entire Indo-Pacific land scape — rather seascape. Underlying animosity in the Korean peninsula, with the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) threatening the neighbourhood with its nuclear devices and missile systems, poses huge risk of conflict. Longstanding territorial disputes and consequently overlapping maritime claims — Kurile and Dokdo islands for instance — between the Northeast Asian countries continue to persist as major irritants. Similarly, conflicting sovereignty claims between China and Japan, over Japanese held Senkaku islands and Chunxiao offshore gas fields in the East China Sea, keeps both the countries on a proactively offensive pitch. The situation on both side of the Taiwan strait continues to remain tenuous, whereby the PLA Navy and Air Force have displayed blatant brinkmanship as a ‘new normal’ — particularly after the contentious visit of US House of Representatives’ Speaker, Nancy Pelosi.

The situation in the South China Sea, where conflicting territorial claims between China, Taiwan, Vietnam and Philippines over islands, rocks and other features in the Paracel and Spratly chain of islands and contentious overlapping maritime zones has persisted for more than half a century, has been on slow boil. The brazen large-scale reclamation of many features, followed by erection of dual-use infrastructure — including airfields on four of them[3] — by China has caused huge consternation among other disputants. Subsequent Chinese efforts at militarisation of these artificial islands is causing great anxieties to the global stakeholders on account of possible disruption of their trade and energy flows through this vital lifeline. The propensity of China to press its territorial and maritime claims in the region by unilateral and unreasonable interpretation of existing international norms, conventions and judgements totally threatens to unravel the international rules-based order. The long-drawn-out negotiations — particularly with ASEAN countries — has created further trust-deficit instead of resolving these vexed issues. In such an uneasy environment, concerted opposition to the Chinese revisionist agenda by regional States as well as affected stakeholders from beyond the region — particularly backed by the proactive US naval stance — does tend to assume ominous portends.

The discordant dynamics in the northern Indian ocean littoral — though a little better than the Pacific side — are still driven by the leftovers of colonial legacy; wherein one odd revisionist State seeks to resolve territorial disputes to its advantage, by resorting to the largely unethical, unfair and sometimes unlawful means. Covert or even overt collusion with some extra-regional States which harbour similar sense of animosity, and dubious expansionist agenda, create serious challenges to the peace and stability in the region. The possibility of precarious situations building in the Persian Gulf, Strait of Hormuz and the Gulf of Oman due to the offensive posture often adopted by Iran vis-à-vis US naval presence and related activities, cannot be ruled out. Sporadic attacks on oil tankers in the area in recent past have raised apprehensions about the possibility of energy supply chain disruption; which could prove to be detrimental to the economic wellbeing of many countries across the Globe.

Apart from these traditional concerns, there are numerous non-traditional challenges plaguing the region. Such threats to national security which arise at-, from- or through the sea are either manmade or take the shape of natural calamities. One just cannot forget the State-supported terror attack at Mumbai in November 2008 — better known as 26/11 — the perpetrators of which used the sea route to execute their perverse agenda. The other threats of major consequence are the piracy, drug running and ‘illegal, unreported and unregulated’ (IUU) fishing. While piracy has been effectively contained through sustained multi-national collaborative effort; continued existence of underlying causes, does raise the possibility of its re-emergence. Of greater concern is the possibility of sinister linkages occurring between pirates and terror groups. The recent seizure of drugs — 2,265 kg heroin and 242 kg methamphetamine — with a market value of $108 million from the Arabian Sea, by the French naval ships of Combined Task Force (CTF)-150 in April-May 2023, indicates the extent of this Malaise.[4] IUU fishing causes huge losses to global economy, in addition to depleting this valuable source of global food security. A Global Financial Integrity report has estimated the annual retail value of drug trafficking up to $ 652 Billion and IUU at $ 36.4 Billion.[5] Natural calamities like cyclones and tsunamis that bring untold misery to the coastal population, need no elaboration. The effects of continuing civil war in Yemen and factional conflict in Sudan tend to spill over into the maritime domain in the shape of refugee crisis and illegal migration; and the consequent need for humanitarian non-combatants’ evacuation operations (NEO) through the sea.

Capability Development to Address Security Challenges

It is therefore all too apparent that the broad spectrum of threats — ranging from traditional ones to multifarious non-traditional types — requires massive capacities and capabilities if they are to be credibly addressed/mitigated. Traditional threats to the national security would, inherently, be country-specific, based largely on their strategic geography, geo-political situation in the neighbourhood, nature and intensity of differences if any, and closeness of alliances/strategic partnerships. Hence, these would, per fore, have to be addressed by individual countries largely by themselves, on the basis of their threat perception. Be that as it may, the countries would still require to invest heavily in naval security hardware, associated infrastructure and operational architecture, in order to ensure that large varieties of non-traditional challenges arising at-, from- or through the sea are either nipped in the bud, or not allowed to assume threatening proportions.

Since the types of resources required to tackle both kind of threats are different in scale, scope and size, the overall force and military capability development would always present a great challenge for a country; particularly against the backdrop of competing national priorities and commensurate fiscal support. Such capabilities should enable the Force to perform its assigned military, diplomatic, constabulary and benign roles in the Country’s areas of maritime interest. The predominant challenge would lie in getting the right balance between the blue-water combat fleet and coastal security vessels. Other issues to consider would be the size and endurance of different-role ships, specific equipment fit thereon, associated training and manning policy, as also integration of military elements with relevant civilian maritime agencies for executing effective response strategies.

The complexity and scale of military capability development would increase further when the vastness of ocean areas that require monitoring, is taken into account. Since the seas are connecting highways through which traditional and non-traditional threats flow quite easily, a nation’s security cannot be assured just by deploying own resources. It, in fact, depends a lot on the response capacities and wherewithal of all States comprising the whole littoral.

India’s Maritime Security Capabilities

Though India has a reasonably robust maritime security set-up, it is just about sufficient to maintain viable security in its surrounding maritime zones. However, the Country would per force, have to contend with additional challenge of keeping its extended maritime neighbourhood secure. This would entail even larger scale development of its military capability, requiring much greater fiscal support — a tall order indeed in the times of pre-existing and omnipresent budgetary constraints. Despite these constraints, India as the de-facto ‘first responder and preferred security partner’[6] in the Indian Ocean, is doing its best to support Sri Lanka, Maldives, Seychelles and Mauritius in increasing their response capacities and capabilities. It is also providing emergency services to other countries, either as humanitarian gesture, or on request. For instance, at China’s request, the Indian Navy’s P8I maritime aerial surveillance aircraft helped in locating the crew of a Chinese fishing mother vessel that capsized about 900 nautical miles (NM) South of India on 18 May 2023; and subsequently guided other Chinese rescue ships to its location.[7] Yet another example is that of Indian Naval Ship Sumedha, which was deployed to evacuate a large number of Indian immigrants — and also other nationals — from Port Sudan in April 2023, as part of OPERATION KAVERI, when that country faced civil war-like situation.[8]

Indeed, the Indian Navy, in addition to being a combat-ready force, has developed credible HADR, SAR, post-disaster response and emergency medical relief capabilities to effectively deal with natural calamities. However, it is obvious that one country alone cannot achieve the desired level of security against wide-spectrum threats, particularly when the area in question is really large. This is where the synergistic collaborative approach between all stakeholders in the Indo-Pacific region is strongly called for.

Strong Case for Jointness in Response Strategies

The Indian Prime Minister, Shri Narendra Modi, while opening a debate at the United Nations Security Council in August 2021, in his capacity as its rotational Chair, laid due emphasis on this very imperative of building international cooperation towards enhancing maritime security. He enunciated the following five basic principles to make the maritime domain safe, secure and stable:[9]

- Remove barriers from legitimate maritime trade.

- Settle maritime disputes peacefully on the basis of international law.

- Face natural disasters and maritime threats created by non-state actors, together.

- Preserve maritime environment and maritime resources.

- Encourage responsible maritime connectivity.

This call for jointness becomes all the more important since many small states in the region do not possess adequate maritime security resources to address myriad challenges in the vast maritime space under their jurisdiction. Seychelles in particular, presents a stark case with regard to woeful lack of maritime security capacity vis-a-vis its entitled Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ), extending for about 1.35 million square kms.[10] Maldives and Mauritius also face similar predicament, albeit at comparatively lesser scale. Going by the dictum that “a chain is as strong as its weakest link”, it is argued that maritime security of the entire region would collectively fall on a few countries which have reasonably strong maritime security capacities and capabilities. The subsequent paragraphs provide a couple of prima-facie recommendations.

Two American Admirals, John Morgan and Charles Martoglio, mooted an ambitious ‘1000-Ship Navy’ concept in 2005, which would entail a network of assigned maritime forces from various States collectively protecting the maritime commons against a wide variety of sea-borne threats.[11] While the idea did not find adequate traction at that time, possibly on account of sheer scale and audacity; the present-day stakeholders in the Indo-Pacific region may seriously consider the same at a much smaller scale, say at about 50-60 ships dispersed across the region in two or three ‘ready response’ flotillas. The concept would possibly require the littoral States to commit some naval or coast guard assets and associated aviation resources to the collective partnership.

Since most of the Indo-Pacific stakeholders acknowledge the centrality of ASEAN in handling matters maritime in the region, an ASEAN body like the ASEAN Defence Ministers Meet Plus (ADMM-Plus) mechanism could initially exercise operational control over these flotillas. The system, once kick-started, could be refined progressively to suit all States’ non-traditional security requirements and contingencies. The existing data processing centres like the India-based Information Fusion Centre-Indian Ocean Region (IFC-IOR), Singapore-based Information Sharing Centre (ISC) and Regional Maritime Information Fusion Centre (RMIFC) in Madagascar could synergise the collation and dissemination of integrated maritime domain awareness (MDA) picture to all partners in the region. Absolute synergy in this endeavour could of course, be achieved if the MDA infrastructure of the US and France — including information from their space-based assets — also gets plugged in.

While the above suggestion may require a certain timeframe for the stakeholders for generating consensus, firm commitment of hardware, formulation of commonly acceptable Command and Control hierarchy and joint operating instructions/procedures; the Indo-Pacific Oceans Initiative (IPOI) as an overarching umbrella of collective maritime security effort, is a more readily available option in the interim. Mooted by the Indian Prime Minister during the 14th East Asia Summit in 2019, the IPOI, as an open global initiative, seeks collective endeavour from States to address various issues in the regional maritime domain across seven interconnected pillars.[12] The IPOI is gradually gaining traction and greater acceptability on account of more and more countries joining its specific pillars. The seven pillars of IPOI[13] are mentioned below, along with the names of States which have consented to actively participate therein — either as leads or otherwise:

- Maritime Security – United Kingdom and India (Joint leads)

- Maritime Ecology – Australia

- Maritime Resources – France

- Capacity Building and Resource Sharing

- Disaster Risk Reduction and Management – India

- Science, Technology and Academic Cooperation – Singapore and Italy

- Trade Connectivity and Maritime Transport – Japan (Connectivity only)

Conclusion

It is quite apparent from the above collation that there is adequate space and enough scope for the other countries to join in the IPOI construct and contribute meaningfully towards collective growth of the regional maritime domain. While this initiative presents the obvious low-hanging fruit with the level of participation/commitment being decided at the discretion of the participant State; the execution of the ‘50-60 ship collective security plan’ will signal firm resolve of the stakeholders in jointly addressing maritime security issues. It would also provide the much-needed teeth and credibility to the venture.

Even though the implementation of such a proposal would certainly be easier said than done, particularly when broad-based consensus — entailing long-term commitment of physical assets and fiscal support from States which have different geopolitical orientations, aspirations and economic situations — could be hard to come by. However, pragmatism dictates that such a collaborative endeavour to address the broad spectrum of maritime security challenges staring the Indo-Pacific region in the face, must be seriously explored. The author is sanguine that with due collective perseverance, the regional maritime security environment will progressively improve; ultimately leading towards a ‘free, peaceful and prosperous’ Indo-Pacific region.

*****

About the Author:

Captain Kamlesh K Agnihotri, IN (Retd.) is a Senior Fellow at the National Maritime Foundation (NMF), New Delhi. His research concentrates upon maritime facets of hard security vis-à-vis China and Pakistan. He also focuses upon maritime issues related to Russia and Turkey. His domain of expertise additionally includes the security dynamics in the Indo-Pacific region. Views expressed in this article are personal. He can be reached at kkumaragni@gmail.com

[1] For maritime security objectives of India and the strategy to be followed towards their fulfilment; see Indian Navy, “Ensuring Secure Seas: Indian Maritime Security Strategy” (Integrated Headquarters, Ministry of Defence (Navy), New Delhi, 2015); hereinafter referred to as ‘IMSS-2015’.

[2] For extent and coverage of India’s primary and secondary areas of maritime interest; see IMSS ibid, 32.

[3] China has built 3000 meters long runways on Woody Island in Paracels; and Subi, Fiery Cross, Mischief Reefs in Spratly chain of islands.

[4] America’s Navy, “French Warship Seizes $108 Million in Drugs during Indian Ocean Seizures”, May 24, 2023, https://www.navy.mil/Press-Office/News-Stories/Article/3405576/french-warship-seizes-108-million-in-drugs-during-indian-ocean-seizures/

[5] Global Financial Integrity, “Transnational Crime and the Developing Word”, March 27, 2017, xi, https://www.gfintegrity.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Transnational_Crime-final.pdf

[6] The terms ‘first responder’ and ‘preferred security partner’ were mentioned by Shri Ram Nath Kovind, President of India at Visakhapatnam on February 21, 2022. See ‘Address by the President of India on the Occasion of Presidential Fleet Review – 2022,’ https://presidentofindia.nic.in/speeches-detail.htm?900.

[7] ANI News, “Indian Navy’s P-81 aircraft locates capsized Chinese fishing vessel in Indian Ocean”, May 19, 2023, https://www.aninews.in/news/national/general-news/indian-navys-p-81-aircraft-locates-capsized-chinese-fishing-vessel-in-indian-ocean20230519205959/

[8] Arindam Bagchi/MEA India, Twitter post, April 25, 2023, 2:56 p. m., https://twitter.com/MEAIndia/status/1650793277812260865

[9] Prime Minister of India Official website, “PM’s remarks at the UNSC High-Level Open Debate on “Enhancing Maritime Security: A Case for International Cooperation”, August 9, 2021, https://www.pmindia.gov.in/en/news_updates/pms-remarks-at-the-unsc-high-level-open-debate-on-enhancing-maritime-security-a-case-for-international-cooperation/

[10] Seychelles Marine Spatial Plan Initiative, “Supporting healthy oceans, communities, and the Blue Economy”, https://seymsp.com/the-initiative/planning-scope/

[11] The proposal was made by the two Admirals at the International Sea Power Symposium at Rhode Island. See Stephen Saunders, “Executive Overview: Jane’s Fighting Ships”,

http://www.janes.com/defence/naval_forces/news/jfs/jfs060612_1_n.shtml

[12] Ministry of External Affairs,” Indo-Pacific Division Brief,” February 7, 2020, https://mea.gov.in/Portal/ForeignRelation/Indo_Feb_07_2020.pdf

[13] Ibid.

Credits: MEA

Credits: MEA

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!