The Indian Ocean, covering approximately 73.6 million square kilometres (21.46 million square nautical miles), constitutes about 20% of the world’s ocean surface. For the purposes of this article, the Eastern Indian Ocean (EIO), as shown in Figure 1,[1] is defined by waters north of 55º South latitude and east of 80º East longitude. It encompasses coastal States surrounding the Bay of Bengal and the Andaman Sea. This region is home to diverse countries with significant populations and faces various security challenges. This article explores the complex nature of one such security challenge, namely, “Irregular Human Migration” (IHM), and examines its drivers, consequences, and the necessity for regional cooperation. By analysing the intersection of security, humanitarian, and environmental factors, this research aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of IHM in the region and advocates the development of effective policies and strategies.

Figure 1. Illustrates the Eastern Indian Ocean, and its coastal States (marked with red)

Source: Lecture Series, ‘Map Familiarisation,’ National Maritime Foundation

The International Organization for Migration (IOM) defines a migrant as “an umbrella term, not defined under international law, reflecting the common understanding of a person who moves away from his or her usual place of residence, whether within a country or across international borders, temporarily or permanently, and for various reasons”.[2] This term encompasses well-defined legal categories such as “migrant workers” and “smuggled migrants”, as well as those whose status is less clearly defined, such as international students. The IOM defines Irregular Human Migration (IHM) as “the movement of people to a new place of residence or transit that takes place outside the regulatory norms of the sending, transit, and receiving countries.”[3] The key issue with these definitions is the lack of legal specificity, covering a broad spectrum from students and workers to trafficked individuals. A detailed analysis of the theme of migration is beyond the scope of this article. Primarily, the focus remains on trafficked and smuggled persons, as well as other illegal migrants who utilise sea routes to clandestinely enter another country. The article’s focus on seaborne illegal migration is germane largely because people, wishing to escape stricter control and surveillance normally experienced at land borders, often embark on perilous sea journeys, facilitated by human traffickers and smugglers who exploit their desperation and vulnerability. The clandestine nature of these voyages not only poses significant risks to the lives of the migrants but also presents considerable challenges to coastal States in terms of law enforcement and border security. As the sea routes become increasingly utilised for illegal access to foreign lands, the need for comprehensive strategies to address the root causes and mitigate the adverse impacts of irregular human migration becomes ever more critical. Consequently, understanding the patterns of such migration is essential for formulating effective policies and cooperative measures among affected countries. It is important to examine the vulnerabilities of the EIO to understand the complexities involved in securing maritime borders and protecting human lives.

Irregular Movement of People and Vulnerability of the EIO

The Western Indian Ocean (WIO)[4] faces severe IHM crises driven by regional instability and resource scarcity, pushing migrants mainly towards Europe.[5] The situation is not much different in the EIO but the intensity varies. In the WIO, the prevalence of weak states and perennial conflicts significantly influence migration trends.[6] In contrast, the littoral States of the EIO are characterised by relatively stronger governance structures and established civil-political institutions. However, despite these institutional strengths, the EIO has a long history of political instability. The region’s history is characterised by separatist movements, sub-nationalist movements, and political upheavals. This historical context underscores the complex and nuanced nature of governance and stability in the region. Moreover, the marine domain’s potential for misuse—ranging from terrorism to piracy—requires a comprehensive security response. This understanding leads to increased scrutiny of human mobility by sea and highlights why it presents a complicated issue for maritime security agencies. The intertwining economic, political, and environmental factors that drive IHM in the region necessitate a nuanced approach. In other words, it is crucial to understand the complexities of IHM as a maritime security threat.

‘Securitising’ Human Mobility: Addressing the Complexities of IHM as a Maritime Security Threat

The sea has served as a conduit for global trade and a cradle of civilisations for centuries. Throughout history, people have navigated these sea routes for a multitude of purposes, whether in times of peace or conflict. The evolution of seas from mare clausum and mare nostrum to mare liberum and from res nullis to res communis may be seen through a historical review of various laws and treaties.[7] As more countries attained naval ascendancy, challenges in the marine space grew, along with the risk profile of these spaces. With globalisation, not only did goods gain access to broader areas, but threats did so, too. Within this context, the increased securitisation[8] of routine activities, such as human mobility, needs to be understood. Securitisation, as developed by Barry Buzan, and Ole Waever, focuses primarily on how security issues influence five sectors: military, environmental, societal, political, and economic.[9] With a ‘widening’ of the use of the term “security”, the number and variety of sectors that can be incorporated within security analysis increase significantly. An issue is said to be securitised when a political audience collectively agrees on the nature of the threat and supports the taking of extraordinary measures, shifting an area of low priority to one of high priority. In other words, the issue becomes a ‘risk’ or ‘threat’ depending upon the ascribed scale of danger. Irregular Human Migration (IHM) is classified as a significant maritime Non-Traditional Security (NTS) threat. Non-Traditional Security (NTS) refers to security-related issues, and threats, that go beyond conventional state-centric military issues, focusing on trans-national challenges like environmental degradation, human trafficking, global health emergencies like epidemics, and illicit drug trade. Such concerns stem not only from inter-State conflicts (which can amplify the impact) but also from transnational issues affecting human security. These issues undermine human security by affecting livelihoods, health, and stability, thereby necessitating a holistic approach to security that integrates humanitarian and development aspects. Just as the term ‘warfare’ is nowadays associated with a range of non-military issues, ‘security-framing’ is deemed an effective way to bring attention to NTS challenges, convey urgency, and command governmental resources to address them. Within the marine domain, the scope of non-traditional security threats addressed by the authorities includes illicit drug trade, IUU (Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated) fishing, armed robbery, piracy, and smuggling, alongside IHM. Irregular migration via sea is particularly significant due to the increasing use of maritime routes for intra- and trans-regional movements, particularly in Asia.[10] Coastal security agencies must handle several vulnerable groups, including victims of trafficking, asylum seekers, stateless persons,[11] and workers on poorly regulated vessels, all facing heightened risks at sea. International Humanitarian Law (IHL), and the relevant provisions of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) address both humanitarian needs and border protection. The intertwining humanitarian and security concerns create a complex dynamic for navies and Maritime Law Enforcement Agencies (MLEAs).

Implications of IHM on Coastal Security

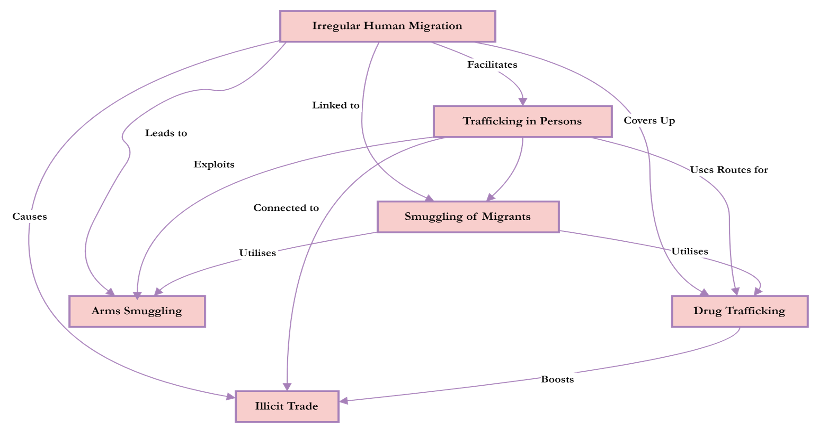

The displacement of minorities, State-on-State conflicts, civil unrest, extreme weather, and economic instability drive mass movements throughout the region. The sea lacks physical barriers, and numerous intermediary spaces exist where government jurisdiction is limited. Overcrowded and unsafe vessels pose risks to maritime safety, potentially causing collisions, engine failures, and fires, and can disrupt legitimate maritime trade. Migrants may stow away on commercial vessels, endangering crew safety and trade. Trafficking networks can connect with organised crime and terrorist groups. After a spate of terror attacks across Europe that mainly involved migrants, there was a vociferous demand to regulate the IHM in the Mediterranean.[12] Security concerns regarding radicalisation have prompted countries like India Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand to pursue ‘push-back’ efforts against the Rohingyas.[13] The concerns of States are not limited to “Violent Non-state Actors” (VNSAs) alone; nefarious elements using vessels carrying migrants to facilitate illegal transport of drugs and contraband apart from the smuggling of arms and commercial goods, are only some of many challenges associated with IHM. Thus, addressing these challenges requires vigilant efforts from states to ensure security. Figure 2 depicts how IHM facilitates several maritime crimes, highlighting the interconnected nature of these issues.

Figure 2. Illustrates the interconnectedness of IHM with other maritime crimes

Source: Author

While the security implications of IHM are significant, it is equally important to consider the humanitarian dimensions. The securitisation of human mobility often overshadows the plight of individuals who undertake perilous journeys in search of safety and better opportunities. Addressing these challenges requires an approach that goes beyond material security concerns. The complexity arises not only from the sheer scale of human migration but also from the varied and often precarious conditions faced by migrants. In multiple instances, people fleeing violence and persecution have undertaken sea journeys, where they are vulnerable to traffickers and inadequate rescue systems. In 2023, the Adriana shipwreck resulted in the loss of more than 600 lives off the coast of Libya.[14] Following this incident, a UNHRC (United Nations Human Rights Commission) ombudsman remarked that there was a failure to ensure that Frontex’s[15] fundamental-rights monitors were sufficiently involved in decision-making. Additionally, there have been reports of migrant vessels in distress encountering difficulties when attempting to contact Frontex. In the Andaman Sea and the Bay of Bengal, it is estimated that one Rohingya has died or gone missing for every eight persons who attempted the journey in 2023.[16] In May of 2015, at least 6,000 migrants from Myanmar and Bangladesh found themselves stranded at sea when smugglers who had promised to take them to Malaysia abandoned them near the Thailand-Malaysia border.[17] The differences regarding jurisdiction and a lack of willingness to accept responsibility for such a politically sensitive issue actively contribute to increased risks and failures of prevention and protection at sea.[18] Moreover, the ‘apprehended’ migrants end up in long-term detention which is a significant humanitarian concern.[19] The proportion of people returning to their countries of origin, or some rehabilitation centre in the recipient country, is far smaller than those who ‘go missing’ afterwards.[20] In essence, the constant need to balance security and humanitarian concerns showcases the depth of challenges the coastal security authorities face in tackling IHM. It requires a nuanced understanding and response, blending humanitarian aid with strict security measures to ensure both the safety and dignity of those affected. India’s experience with IHM offers valuable insights in this direction.

Coastal Security and the IHM: An Indian Experience. India’s maritime history spans centuries, with trade routes fostering cultural exchange but also serving as entry points for colonial powers.[21] India’s holistic maritime security involves freedom from threats arising in, from or through sea. India’s location along key maritime routes fuels its trade yet exposes it to maritime threats. This vulnerability was starkly evident in the case of the 1993 Blasts and the 2008 Mumbai attacks, where sea routes were exploited by the perpetrators.[22] India’s maritime security is complicated by unsettled territorial issues with Pakistan and China. India’s proximity to the illegal drug trade bastions of the Golden Triangle and Golden Crescent adds to its security concerns.[23] The smuggling of goods, contraband, and natural resources from coastal states, as also increasing IUU fishing, all pose significant economic security challenges.[24] The Indian Navy is the principal maritime force of the Republic of India.[25] The multitude of roles the Indian Navy plays can be categorised broadly as the military role (which is the basic one), the diplomatic role, the constabulary (policing) role, and the benign (humanitarian) role.[26] The Indian Coast Guard (ICG) complements these efforts by enforcing maritime law, safeguarding India’s coastline, and performing essential duties such as search and rescue operations, pollution control, and protecting marine resources. Together with the coastal police, these forces ensure a robust maritime security framework for the region. In the context of IHM, the Indian Navy and the ICG face the challenge of countering violent non-State actors in vessels carrying undocumented people. It is not easy to separate inimical elements from benign ones. The Sri Lankan Tamil crisis highlighted this. In 1990, the Indian Navy, along with the Indian Coast Guard and the Coastal Police launched Operation TASHA to tackle illegal activities and unauthorised immigration between India and Sri Lanka. This operation was aimed to counter the LTTE’s growth in the Gulf of Mannar and Palk Bay, and to provide humanitarian aid to those fleeing violence.[27] Locally, Tamil fishermen were also involved, aiding Sri Lankans in crossing illegally. It highlighted the intersection of humanitarian and security issues. There were also accusations that Tamil refugees fleeing Sri Lanka were charged hefty fees to reach India, similar to situations observed in Libya and Syria. The Indian Navy and the ICG rescued hundreds of people and relocated them in makeshift rehabilitation centres supported by the Tamil Nadu government and the UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees), India. [28] India has not faced irregular migration on the same scale as have countries such as Bangladesh, but even episodic occurrences, such as the influx of Tamils during the Sri Lankan crisis, have presented significant challenges. While India’s experience provides valuable insights into managing irregular human migration (IHM), it is crucial to recognise that addressing this issue requires concerted efforts from all stakeholders. The interconnected nature of the problem underscores the need for collaboration among coastal States to address the root causes of irregular migration and to devise effective strategies.

Need for Regional Cooperation

Enhancing regional cooperation is crucial for addressing issues that could become ‘inflection points’ for much larger crises. In the EIO, certain factors have the potential to exacerbate the problem of IHM beyond manageable levels. According to the IOM, these ‘new’ displacement trends refer to the displacement caused by conflicts and/or disasters.[29] Effective regional collaboration is necessary to manage these challenges and prevent them from escalating into larger crises.

Changing Contours of Political Conflicts. Asia and Africa account for 75% of active conflicts.[30] Bangladesh and Myanmar rank amongst the top ten countries in Asia in terms of population displaced by conflict, as shown in Figure 3. Myanmar experienced its most significant internal displacement in 2022, with over a million people, primarily Rohingyas, being displaced.[31] This marks the highest number ever recorded for the country, and was driven by intensified clashes between the military and non-State armed groups. Myanmar ranks second in terms of conflict-induced displacement relative to its population, after Kyrgyzstan.[32] Moreover, neighbouring countries such as Indonesia, India, and Thailand, emerged as key destinations for people fleeing violence in Myanmar. Indonesia occupies a pivotal position due to its strategic location and archipelagic geography, serving as a preferred transit point for migrants seeking access to countries like Canada and the US. It sits astride key maritime chokepoints such as the Malacca Strait, the Lombok Strait, the Sunda Strait, and the Ombai-Wetar Strait, making the country vulnerable to the smuggling of arms, contraband, and other illicit materials alongside migrant flows.[33] However, the resultant situation is not unique to Indonesia. From a regional perspective, the problem is compounded by the fact that many countries have not signed the 1951 Refugee Convention, resulting in legal ambiguities.[34] Additionally, inter-ethnic and cross-communitarian ties between illegal migrants and residents complicate the issue. State responses to illegal migrants are influenced by domestic constraints and factors. The broadening horizon of increased geopolitical competition has led to the emergence of new political equations. The repercussions are felt across borders, as seen in overcrowded coastal districts in Bangladesh such as Cox’s Bazar,[35] and in political unrest in Indonesia, with both countries grappling with the impact of the illegal movement of the Rohingyas.[36] Myanmar’s strategic position between India and China affords it significant political leverage. As a result, addressing the country’s crisis management at the regional level results in a more measured approach rather than direct accountability. The strategic significance of the EIO has led to increased military presence by major powers, which in turn affects regional stability. This heightened security-focus results in stricter measures of surveillance, and more restrictions on human mobility. As maritime areas become more securitised, it presents humanitarian challenges for those fleeing violence or caught in conflicts. The interplay between security measures and humanitarian needs requires careful management to ensure that efforts to maintain stability do not adversely impact vulnerable communities.

Climate Change and Vulnerability of the EIO

In addition to the changing contours of conflict, climate change, too, is emerging as a significant driver of irregular human migration in the Eastern Indian Ocean. The increasing frequency and intensity of natural disasters are exacerbating existing vulnerabilities and creating new challenges for coastal States.

The Indian Ocean is experiencing accelerating sea-level rise as compared to the global average.[37] Moreover, the frequency of extreme weather events has risen from once-in-a-decade to once-in-a-year.[38] The cumulative effect of these threats worsens the vulnerability of coastal areas.[39] The Sundarbans delta and the Sumatra region are prone to extreme weather events such as cyclones and, indeed, the Bay of Bengal accounts for over 80% of cyclone fatalities.[40] It is also important to note that the region is very prone to natural disasters. For example, because of the weather-prone geography of the east coast of India, most trade and transit remained oriented to the west coast of India.[41] From a historical perspective, floods and sea surges have been part of the history of the states lying on the east coast of India.[42]

| Country | Rank (2008) | Rank (2050) | Vulnerable Population (Millions) (2008) | Vulnerable Population (Millions) (2050) |

| India | 1 | 1 | 20.6 | 37.2 |

| Bangladesh | 3 | 2 | 13.2 | 27 |

| China | 2 | 3 | 16.2 | 22.3 |

| Indonesia | 4 | 4 | 13 | 20.9 |

| Philippines | 6 | 5 | 6.5 | 13.6 |

| Nigeria | 9 | 6 | 4.3 | 9.7 |

| Vietnam | 7 | 7 | 5.7 | 9.5 |

| Japan | 5 | 8 | 9.8 | 9.1 |

| USA | 10 | 9 | 3.8 | 8.3 |

| Egypt | 17 | 10 | 2.1 | 6.3 |

| UK | 11 | 11 | 3.3 | 5.6 |

| South Korea | 8 | 12 | 4.8 | 5.3 |

| Myanmar | 12 | 13 | 2.8 | 4.6 |

| Brazil | 14 | 14 | 2.6 | 4.5 |

| Turkey | 13 | 15 | 2.6 | 3.9 |

| Malaysia | 18 | 16 | 1.9 | 3.5 |

| Germany | 15 | 17 | 2.3 | 3.3 |

| Italy | 16 | 18 | 2.1 | 2.9 |

| Mozambique | 25 | 19 | 1.2 | 2.8 |

| Thailand | 19 | 20 | 1.8 | 2.6 |

Table 1. Represents the vulnerability of differences from climate change

Source: David Wheeler, Centre for Global Development

Similarly, as per Table 1[43] above, most of the countries at high risk of climate change-related vulnerability belong to the EIO. The important point, however, is that these trends will remain unchanged in the future. This clearly indicates that measures implemented thus far are not enough; more is required from the stakeholders.

| Country | Displacement (in millions) |

| Pakistan | 8 |

| Philippines | 6 |

| China | 4 |

| India | 4 |

| Bangladesh | 3 |

| Myanmar | 2 |

| Yemen | 1 |

| Viet Nam | 1 |

| Indonesia | 0.5 |

| Afghanistan | 0.5 |

| Syria | 0.5 |

| Kyrgyzstan | 0.2 |

| Malaysia | 0.2 |

| Nepal | 0.2 |

| Iraq | 0.2 |

| Japan | 0.1 |

| Iran | 0.1 |

| Republic of Korea | 0.1 |

| Cambodia | 0.1 |

| Thailand | 0.1 |

Table 2. Shows the ‘new’ displacement trends

Source: 2024 World Migration Report, IOM

As per Table 2, coastal States of the Indian Ocean are notably impacted by disaster-caused human displacement.[44] The scattered nature of the data raises validity concerns, but its frequency suggests that displacement may evolve into established migratory patterns. These evolving patterns highlight two things: the scale of displacement is expanding in an unassailable way, despite its ‘internal’ character, and the vulnerability of coastal areas remains critical, despite the measures implemented. The challenges faced during recent natural disasters further underscore these issues. For instance, in the immediate aftermath of the 2004 earthquake and resultant tsunami, Coast Guard officials had to intensify search and rescue efforts in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands despite facing challenges such as limited manpower, restricted accessibility, and inadequate infrastructure.[45] In other words, “when erratic precipitation and extreme events are added, areas that are barely holding on might find themselves slipping over the brink.”[46] The spillover effects of these environmental issues are distinctly evident in the coastal areas of the region.[47] The persistent risk of widespread displacement creates complex challenges for coastal authorities, highlighting the need for better preparedness.

In Figure 4,[48] various risk factors associated with climate change outline the broad-ranging impacts on livelihoods and food security.[49] Such trends fuel unrest, and result in forced migration from the affected areas (marked as the dashed portion of the picture). For instance, the 1971 war saw large-scale illegal migration to India’s east coast, particularly Assam and West Bengal where the incursion of Bangladeshi migrants created widespread problems.[50] Similarly, from a security perspective, climate change is a threat multiplier.[51]

Figure 4. Depicts the Climate-Risks resulting into various issues.

Source: Lecture Series, ‘Climate Change,’ National Maritime Foundation

At the global level, the COVID-19 (Coronavirus Disease, 2019) pandemic underscores the risks associated with the intersection of multiple disasters. Previous outbreaks like the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) and the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) were significant, but COVID-19’s unprecedented scale triggered a global cascade of crises. Existing geopolitical tensions, financial market turmoil, and protectionist policies had already disrupted trade sectors, straining public goods systems and prompting navies to ensure the continued flow of essential goods.[52] Climate change presents a more disruptive challenge. Moreover, the lack of consensus regarding definitive aspects is an area of concern.[53] For example, Bangladesh’s NCAP (National Climate Adaptation Plan) mentions climate refugees (one of the few countries in the region to use that term), but it does not fully encompass those affected by statelessness, conflict, and disaster, such as the Rohingyas in Cox’s Bazar.[54] What provisions are in place for managing multifaceted migration scenarios? How will law enforcement and border security agencies address these complex cases? Which laws are applicable, and which are not? These are critical questions that must be addressed. Despite high vulnerability, most countries have not come up with any effective mechanism to deal with the problem at the regional level. The growing humanitarian crisis, exacerbated by climate change, highlights the urgent need for effective regional cooperation. While various regional arrangements exist to address irregular migration, their implementation and effectiveness vary significantly.

UNCLOS Provisions. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) includes several provisions relevant to humanitarian assistance, although its primary focus is to promote a rules-based maritime order. Therefore, the convention attempts to strike a balance between the States’ need to guard the sea and keep it accessible. Article 98 obliges states to assist vessels in distress, including rescuing migrants at sea.[55] Article 99 prohibits trafficking in persons and requires measures to suppress such activities.[56] However, coastal States have sovereignty over their territorial seas under Article 2 and can enforce immigration laws within their contiguous zones as specified in Article 24.[57] In the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), while primarily for economic purposes, states can enforce immigration laws consistent with international law.[58] On the high seas, Article 87 allows states to control their ships and prevent illegal activities, such as trafficking.[59] Article 197 calls for international cooperation to protect the marine environment, which can indirectly impact migration issues, such as environmental impacts from overcrowded boats.[60] Although UNCLOS provides crucial maritime safety and security frameworks, it is not sufficient to fully address the issue.

Global Frameworks.

(a) The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) operates globally, including in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR), to address refugee movement, provide humanitarian aid, and support refugees and migrants.[61]

(b) The UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) is another key global organisation that works with Indian Ocean countries to combat trafficking in persons and irregular migration through various projects and initiatives.[62]

(c) The Global Compact for Refugees (GCR),[63] adopted by the UN General Assembly in 2018, aims to enhance international cooperation and responsibility-sharing for refugee protection. It offers a framework for predictable and equitable support to host countries and communities, fostering resilience and self-reliance for refugees.

Current Regional Arrangements Addressing IHM

It is important to note that although there are a few regional arrangements that address the challenge of IHM in varying ways, it is disturbing to find that despite the scale of the problem, regional mechanisms have not been well focused, and rather, tend to address the problem indirectly and quite broadly. Some of current arrangements are:

(a) ASEAN. ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) Member States are affected either as a source, transit, or destination for migrants.[64] The Emergency ASEAN Ministerial Meeting on Transnational Crimes (EAMMTC) recommended the establishment of Heads of Specialist Unit (HSU) on People Smuggling to work in tandem with the HSU on Trafficking in Persons (TIP), which was established in April 2004 under the Senior Officials Meeting on Transnational Crime (SOMTC), held in July 2015.[65] ASEAN spearheads several relevant instruments, including the ASEAN Declaration Against Trafficking in Persons, Particularly Women and Children (ACTIP) and the ASEAN Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Rights of Migrant Workers (ACPW) to address the problem.

(b) Regional Arrangements in the Indian Ocean. The IORA (Indian Ocean Rim Association) recognises IHM as a key maritime security threat in its charter. The IONS (Indian Ocean Naval Symposium), an India-led regional initiative, promotes naval cooperation and enhances maritime security in the IOR, including addressing the challenges associated with irregular movement of people. However, owing to the diverse constitution, and wide-ranging functions, these mechanisms often lack the requisite element of specificity.

(c) Other Regional Arrangements. As part of security considerations, SAARC (South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation) enacted a few directives aimed at enhancing security against terrorism, drug trafficking, child and women trafficking, and other transnational crimes, which are common social challenges in the region.[66] BIMSTEC (Bay of Bengal Multi-sector Technical and Economic Cooperation) also recognises trafficking in persons (TIP) as a grave transnational organised crime.[67] The development of regional and inter-regional consultative processes such as the Bali Process (against trafficking),[68] the Colombo Process, and the Abu Dhabi Dialogue (for regulating labour migrant movement) also consider IHM as a transnational crime.[69] Despite their potential, these mechanisms often encounter obstacles and limitations in addressing the issue because they lack ‘enforceability’.

Challenges and Limitations

Despite their potential, most of these mechanisms often encounter obstacles and limitations in addressing the issue. The absence of a unified definition of IHM hampers data-collection and analysis, making it challenging to understand migration patterns and develop effective policies. National laws and policies vary significantly across the region, with some countries having robust anti-trafficking frameworks while others lack the necessary legal infrastructure. This ‘patchwork’ approach creates inconsistencies in addressing IHM and impedes regional cooperation. For instance, the “Principles of Bangkok on the Status and Treatment of Refugees”, adopted in 1966 and finalised in 2011, are non-binding and aimed at inspiring national legislation. A draft of the “Convention Against Trafficking in Persons” has been prepared by BIMSTEC but it is yet to take tangible shape.[70] Existing frameworks, such as the “Bohol Plan” (2017-2020),[71] often struggle with implementation and enforcement due to resource-constraints and a lack of monitoring mechanisms. ASEAN proposed a “Joint Task Force” to address trafficking and illegal migration but this, too, has not yet materialised.[72] Within large regional groupings such as IONS, as well as IORA, many member States are developing nations and lack sufficient resources for building requisite maritime capability for themselves, lack a ‘unifying’ political framework, and are faced with the absence of a cohesive organisational structure.[73] Therefore, such limitations undermine the efforts to contain the issue.

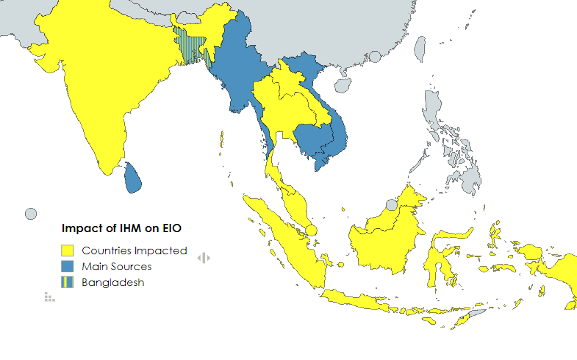

Figure 5. Impact of IHM on various countries in the EIO.

Source: Author

Converging Crisis and the Road Ahead.

Figure 5 shows the main sources of IHM, and the countries most significantly impacted. Bangladesh has been a significant recipient-of and has substantially contributed-to IHM in the region. Moreover, the country’s coastal areas are highly vulnerable to the impact of climate change. Therefore, Bangladesh serves as a good example with which to understand the potential impact on a country of multiple disasters. Other countries in the region also face similar problems. In other words, the region does not face a single set of problems, it faces a ‘convergence’ of multiple serious challenges. Hence the need to develop response mechanisms at the regional level, and not rest content with national, reactive ones. Facing this multiplicity of crises requires multiple approaches from all stakeholders.

Need for Collective Responsibility over Single-point Responsibility. Strengthening the current regimes is one way in which to reach a consensus. For instance, the role of BIMSTEC could and should be expanded to serve as a forum for focused informal discussions or formal mediation on IHM (i.e., an issue-specific approach). There are other options as well that need to be explored. Perhaps instead of centralised multilateral arrangements that work on the premise of single-point responsibility, it might be better to have decentralised yet interdependent arrangements.[74] These may well be particularly important in an environment of high uncertainty, such as in the case of climate change, where the most demanding international commitments are interdependent yet governments vary widely in their interest and ability to implement such commitments.[75] Comprehensive international regulatory institutions that are focused on a single integrated legal instrument, lie at one end of the spectrum, while highly fragmented arrangements lie at the other.[76] Between these two extremes are nested regimes and regime complexes, which are loosely coupled sets of specific regimes. These intermediate structures offer a more flexible approach to governance, allowing for tailored responses to complex issues. For instance, plurilateral arrangements, with security federalism as a framework, could enhance responses to specific challenges like IHM: “In a ‘pluralistic security community’, federalism is achieved before functionalism, and pluralistic security is, therefore, a particularly useful framework for integration in the face of domain-specific security challenges.” [77] Moving from single-point responsibility to collective responsibility, where multiple entities collaborate in a decentralised yet interdependent way, is essential. Recent years have also seen a rise in “soft law” instruments — non-binding declarations and resolutions — which, while not legally enforceable, can pave the way for binding laws. For example, despite the lack of legally binding provisions, the “Bali Process” facilitates consensus on complex issues like trafficking and fosters shared understanding among States. Another way of addressing the problem is to adopt “small-group reciprocity” in which a small number of identifiable players can monitor one another’s behaviour and can sanction, through reciprocity, agents who refuse to accept jointly agreed rules or who fail to comply with rules. This could be an effective way of dealing with issue-specific challenges. The Colombo Security Conclave (CSC) can be taken as an example of this. In 2011, the CSC started out as a trilateral initiative involving Sri Lanka, Maldives and India. Later, Bangladesh and Seychelles joined as observers. Initially oriented towards “white shipping” agreements (particularly to address the issue of smuggling), the construct has evolved to become an operational framework whose scope encompasses enhancing cooperation, sharing best practices and procedures to counter maritime crimes, providing mutual assistance for SAR States, and sharing/exchanging intelligence and information among states.[78] Similarly, the Quad (Quadrilateral Security Dialogue involving India, Japan, Australia, and the US)[79] can provide much-needed gravitas to the issue, given that the forum includes regional and extra-regional powers. The Quad’s focus on holistic maritime security could be utilised to ensure focused discussions on IHM, strengthening joint efforts and strategies. Inter-regional arrangements, such as the signing of the ASEAN-IORA MoU (Memorandum of Understanding), could be leveraged to address the multi-faceted character of IHM.[80] A blend of plurilateral arrangements, soft law instruments, and collaborative frameworks, offers a comprehensive approach to tackling IHM, underscoring the importance of both formal and informal mechanisms in addressing migration challenges.

Protecting Human Rights and Engaging with Civil Society. Despite not being parties to key legal instruments on migration, countries in the region are committed to upholding human rights through agreements such as the “Universal Declaration of Human “Rights (UDHR), the “UN Convention against Transnational Organised Crime” and its “Trafficking in Persons Protocol”,[81] the “Convention on the Rights of the Child” (CRC),[82] and the “Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women” (CEDAW).[83] Their participation in mechanisms such as the “UN Global Plan of Action to Combat Trafficking in Persons”,[84] and the “Global Compact on Migration” also calls for immediate needs and root causes of irregular migration.[85] Regional mechanisms such as the “ASEAN Declaration on the Rights of Children in the Context of Migration”,[86] and the “ASEAN Gender Sensitive Guideline for Handling Women Victims of Trafficking in Persons” provide valuable tools.[87] In one way or another, these instruments require States to address the humanitarian aspects of the problem. One way to go about this is to engage community organisations, which can, thereafter, offer insights into local contexts and foster support for regional strategies. Humanitarian Diplomacy, focusing on trust-building between internal and external actors, can enhance communication and collaboration despite political differences, ensuring security and dignity for migrants.[88]

Leveraging Technology and Strengthening Regional Coordination

The misuse of technology, especially through social media and online platforms, has complicated efforts to combat trafficking in persons (TIP). The “ASEAN Leaders’ Declaration on Combating Trafficking in Persons Caused by the Abuse of Technology” (2023) marks a significant step in addressing this issue.[89] Harmonising definitions of IHM and standardising data collection processes are crucial for understanding migration patterns. Regional data-sharing platforms and Information Fusion Centres (IFCs) like the IFC-IOR (Indian Ocean Region) enhance maritime domain awareness and coordination.[90] The Quad-led IPMDA (Indo-Pacific Maritime Domain Awareness)[91] initiative should be utilised to enhance the gathering, collation, and utilisation of data on undocumented migration. Coordinated patrols and search and rescue (SAR) mechanisms, along with trans-regional agreements like the ASEAN-Australia Counter-Trafficking (ASEAN-ACT) partnership, too, are vital for disrupting smuggling networks and improving maritime security.[92] Enhancing vessel-tracking systems and addressing gaps in national legal frameworks through regional mechanisms such as ASEAN’s “Mutual Legal Assistance Agreements” (MLATs) are essential for supporting cross-border investigations.[93] A cohesive, technology-driven, and regionally coordinated approach is crucial for managing and mitigating the impacts of IHM effectively.

Capacity Building, Capability Enhancement, and Resource Sharing.

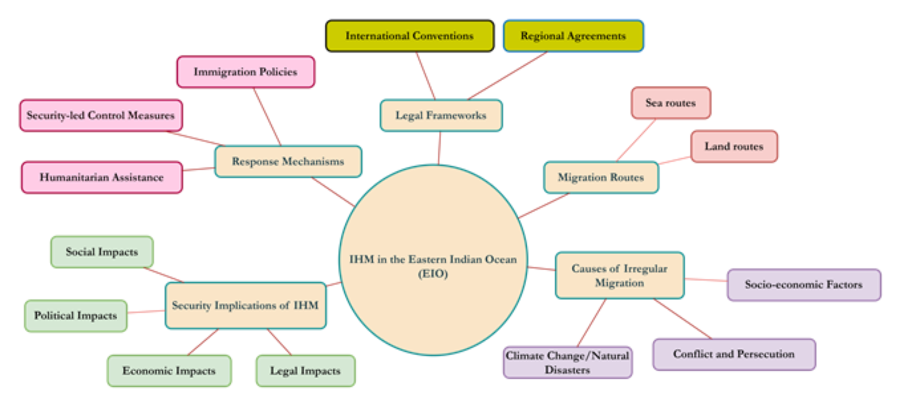

Effective management requires capacity building, capability enhancement, and resource sharing. Countries with expertise can share best practices and provide training to bridge gaps in manpower and infrastructure. Functional approaches to resource-sharing can improve regional capabilities in border management, search and rescue operations, and victim protection. However, planned relocation and rehabilitation often face challenges in a trans-regional context, due to differing national priorities and capacities. Figure 6 depicts a variety socio-political, socio-legal, and socio-economic facets of IHM. The ‘interconnectedness’ of various elements visually underlines the intricacy of the problem at hand. More effective steps are needed to enhance coordination, while collaboration is necessary to overcome these limitations and ensure a cohesive regional response to IHM.

Figure 6. Illustrates various facets of IHM in the Eastern Indian Ocean

Source: Author

India’s Role

As a key naval power in the Indian Ocean, India relies upon the region for commercial shipping, energy importation, trade, tourism, and fishing. Under the Indian Navy, India prioritises the entire Indian Ocean, from the eastern coast of Africa to the Andaman Sea, as its area of primary focus. India’s approach to maritime security is exemplified by initiatives such as multi-agency manoeuvres like Operation AJHE-CHAKRAVAT, which is one of the joint manoeuvres undertaken to address HADR (Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief (HADR) in the region.[94]

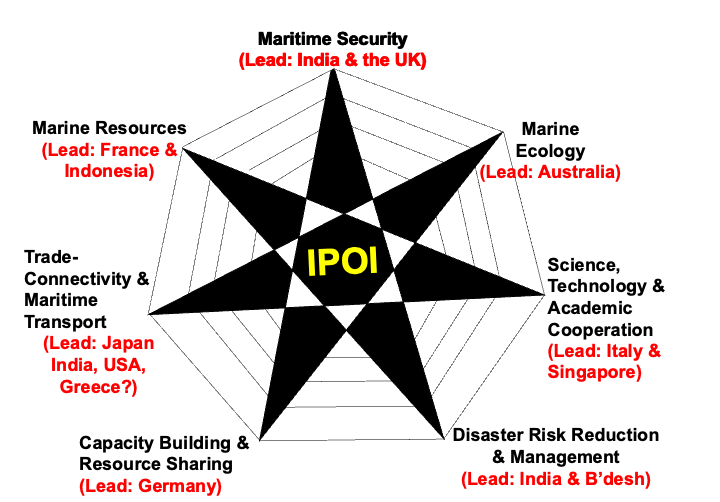

At the regional level, India’s potential is exemplified by policies such as SAGAR (Security and Growth for All in the Region), for which first-order-specificity is provided by the Indo-Pacific Oceans Initiative (IPOI). As shown in Figure 7,[95] the IPOI, with its seven thrust areas or ‘spokes,’ promotes a ‘rules-based order’ in the Indo-Pacific; India and the UK collaboratively lead the Maritime Security thrust area. Additionally, India leads the initiative in Disaster Risk Reduction and Management. In both these areas, more focus can be given to devising practical solutions for IHM.

Fig 7. The Indo-Pacific Oceans Initiative and its seven deeply interconnected thrust areas.

Source: Lecture Series, ‘Geopolitics,’ National Maritime Foundation

India can utilise its influence at both bilateral and multilateral levels. More effective steps like the MoU between Myanmar and India (to enhance relief efforts for those affected by violence in Rakhine)[96] and/or between the Indian Coast Guard and the Bangladeshi Coast Guard, can be taken.[97] Other bilateral measures — such as the Coordinated Patrols (CORPAT) between India and Indonesia — can be leveraged as well.[98] The imperative of regional cooperation is building bridges, not walls. India has the potential to be that bridge. The limitations of existing frameworks underscore the critical need for enhanced regional cooperation on IHM in the EIO. By fostering partnerships and leading regional efforts, India can bridge gaps, and enhance regional responses to irregular migration.

Conclusion: Need for a Collaborative Approach

IHM in the EIO presents a multifaceted challenge that demands urgent, and decisive action. To effectively address this issue, it is not enough to merely strengthen existing frameworks or adopt a piecemeal approach. Instead, a concerted, regional effort is imperative — one that integrates human rights considerations, tackles political instability, and addresses the adverse effects of climate change. The complexity of IHM in the EIO, albeit perhaps less immediate than conflict-driven migration in the Western Indian Ocean (WIO), is nonetheless significant. Migration through the Bay of Bengal and the Andaman Sea, exacerbated by environmental disasters and political upheaval, underscores the urgency of a comprehensive strategy. The strategy must be more than a series of reactive measures; it requires proactive and collaborative engagement among regional stakeholders. A collective regional approach must prioritise human rights, ensuring the dignity and safety of those fleeing violence and persecution. It should address the root causes of migration rather than merely responding to the symptoms. This requires developing mechanisms for information sharing, coordinating responses, mutual enhancement of capabilities and building capacity to handle the complexities of IHM effectively. India, as a regional leader, has a crucial role to play in spearheading these efforts. By leveraging its influence and resources, India can drive a regional strategy that not only enhances security but also fosters stability and resilience. Through a unified approach that embraces collaboration and comprehensive planning, the Indian Ocean region can secure a safer and more sustainable future for migrants and the entire region. This should encompass strengthened regional collaboration, including enhanced platforms for sharing information and building capacity amongst member states. Prioritising humanitarian assistance, particularly search and rescue operations, is essential. Aligning national laws and policies to combat human trafficking and smuggling at the regional level is vital. Moreover, integrating climate change adaptation measures into migration policies is necessary. Finally, addressing IHM in the Indian Ocean requires more than just strengthening rhetoric; it demands a collective, regional effort that integrates human rights, political stability, and climate resilience. Only through an inclusive approach, we can hope to navigate the complex landscape of irregular migration and ensure a secure and humane future for all.

******

About the Author

Ms Meher Fatima holds a Masters degree in Politics (International and Area Studies) from the Jamia Millia Islamia University, New Delhi and is deeply interested in the maritime facets of irregular human migration. She penned this research article while undergoing a six-month internship at the National Maritime Foundation (NMF) from February to August 2024. She may be contacted at mehr4301@gmail.com

Endnotes:

[1] Captain Ranendra Sawan, “Map Familiarisation.” Lecture Series, National Maritime Foundation. 26-27 February, 2024

Marking (as depicted by the red line) is done by the author on the source image to depict the Eastern Indian Ocean as relevant to this research article.

[2] International Organisation for Migration (IOM), “Key Migration Terms,” https://www.iom.int/key-migration-terms

[3] IOM, “Key Migration Terms”

[4] The Western Indian Ocean, which comprises the littoral and island states of eastern and southern Africa. This region stretches from Somalia in the north to South Africa in the south, encompassing the south-western Indian Ocean Island States.

Anum Khan, “Data as a Facilitator in Maritime Risk Profiling of the Western Indian Ocean (WIO),” National Maritime Foundation, April 21, 2024, https://maritimeindia.org/data-as-a-facilitator-in-maritime-risk-profiling-of-the-western-indian-ocean-wio/.

[5] Missing Migrants Project “Mediterranean,” 2014, https://missingmigrants.iom.int/region/mediterranean.

[6] M Bayar and MM Aral, “An Analysis of Large-Scale Forced Migration in Africa,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 16(21), 4210, October 30, 2019,

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6861999/

[7] Roman law forms the basis of the whole European legal system. Concepts such as ‘mare liberum’ (the seas being open to all nations), ‘mare clausum’ (the seas being under the sovereignty of a power and restricted in terms of use by other States) and ‘mare nostrum’ (‘our’ seas) all reflect Roman legal philosophy and formed part of the ancient ‘Law of Nations’ (Jus Gentium)

Source: Vice Admiral Pradeep Chauhan, “PIML Overview,” Lectures at the National Maritime Foundation, 05-08 March 2024

[8] Clara Eroukhmanoff, “Securitisation Theory: An Introduction,” E-International Relations, January 14, 2018, https://www.e-ir.info/2018/01/14/securitisation-theory-an-introduction/.

See also: RJ Kilroy, “Securitization,” in Handbook of Security Science (Springer Publications, 2018), https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-51761-2_11-1.

[9] Eroukhmanoff, “Securitisation Theory”

[10] ESCAP (Economic and Social Commission for Asia-Pacific). “The Asia-Pacific Riskscape: How Do the Changes in Weather, Climate and Water Impact Our Lives?” 23 March 2023. https://www.unescap.org/blog/asia-pacific-riskscape-how-do-changes-weather-climate-and-water-impact-our-lives.

[11] The term ‘stateless person’ means a person who is not considered as a national by any State under the operation of its law.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. (UNHCR). “Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons.” https://www.unhcr.org/ibelong/wp-content/uploads/1954-Convention-relating-to-the-Status-of-Stateless-Persons_ENG.pdf

See also: Myrion Weiner, “Rejected Peoples and Unwanted Migrants In-South Asia,” Economic and Political Weekly (EPW), August 1993.

See also: Katy Gardner and Filippo Osella. “Migration. Modernity and Social Transformation in South Asia: An Overview.” Contributions to Indian Sociology. February 2003. 15-18 https://doi.org/10.1177/006996670303700101

[12] Ali Özgür and M İnanç Özekmekçi, “EU Initiatives to Prevent the Terror Threat in the Mediterranean,” Journal of Applied and Theoretical Social Sciences, 2022. 39-56. https://doi.org/10.37241/jatss.2022.47

[13] Niloy Ranjan Biswas, “Maritime Migration in the Bay of Bengal and the Indian Ocean: A dire need for greater cooperation.” Indo Pacific Circle, July 2022. https://www.ipcircle.org/op-eds/maritime-migration-in-the-bay-of-bengal-and-the-indian-ocean%3A-a-dire-need-for-greater-cooperation.

[14] An overcrowded fishing trawler, named Adriana overturned on the morning of June 14, 2023, near Greece. It resulted in the deaths of over 600 individuals. The vessel had set off from Libya five days earlier, carrying approximately 750 migrants and asylum seekers, including children, primarily from Syria, Pakistan, and Egypt. Only 104 people survived, and 82 bodies were recovered.

See: Nicholas Niarcos, “Why Hundreds Drowned Off the Coast of Greece?,” The New Yorker, June 26, 2023, https://www.newyorker.com/news/daily-comment/why-hundreds-drowned-off-the-coast-of-greece

[15] “Frontex” is the name of the European Border and Coast Guard Agency. Established in 2004, it assists national authorities through various operations and training. The agency’s role has expanded significantly, especially in response to the recent migrant crisis, emphasising the need for security while upholding fundamental rights. It supports EU and Schengen countries in the management of the EU’s external borders and the fight against cross border crimes. See www.european-union.europa.eu

[16] Mullaly,13 “Trafficking in Persons,” 4

[17] Reports indicate that thousands of Rohingyas were stranded at sea after being abandoned by smugglers and traffickers who had falsely promised them jobs in Malaysia, Thailand, and Indonesia. Consequently, many were left to fend for themselves. A particularly significant incident involved the discovery of over 200 graves, mostly of Rohingyas, along Thai-Malaysia border which drew considerable attention from humanitarian authorities.

See: Associated Press Report, “Malaysia and Thailand turn away hundreds on migrant boats.” The Guardian, May 14, 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/may/14/malaysia-turns-back-migrant-boat-with-more-than-500-aboard.

See also: Associated Press Report, “Malaysia Charges Four Thais Over 2015 Mass Graves, Refugee Camps,” Al Jazeera, June 23, 2023, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/6/23/malaysia-charges-four-thais-over-2015-mass-graves-refugee-camps

[18] Mullaly,13 “Trafficking in Persons,” 6

See also: International Organization for Migration, “Missing Migrants: Asia,” 2014, https://missingmigrants.iom.int/region/asia.

[19] Hui Yin Chuah, “Rohingya Protection in Asia: Navigating Protection Gaps Amid Shifting Geopolitics,” Mixed Migration Centre, June 2023, https://mixedmigration.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/282_Rohingya-Protection-Asia-1.pdf. 1-9.

[20] Chuah,19 “Rohingya Protection in Asia.” 3, 5, 6.

[21] Captain Ranendra Sawan, “India’s Maritime Identity,” National Maritime Foundation website, 18 January 2023, https://maritimeindia.org/indias-maritime-identity/.

[22] Captain Himadri Das, Coastal Security: Policy Imperatives for India, (National Maritime Foundation, 2022), Chapter 1, 12-90

[23] Golden Triangle includes parts of Myanmar, Laos, and Thailand. It is known for widespread cultivation of opium for illicit trade. Similarly, the Golden Crescent refers to parts of Iran, Afghanistan and Pakistan that is known for illegal drug, particularly opium, production.

See: Captain Himadri Das, “Drug Trafficking in India: Maritime Dimensions,” National Maritime Foundation website, 31 December, 2021, https://maritimeindia.org/drug-trafficking-in-india-maritime-dimensions/

[24] Captain Himadri Das, “Maritime Safety and Security in India: Fisheries “MCS” a Key Enabler,” National Maritime Foundation website, 21 November, 2021, https://maritimeindia.org/maritime-safety-and-security-in-india-fisheries-mcs-a-key-enabler/.

[25] The Indian Navy, Indian Maritime Security and Safety (IMSS), “Strategy for Coastal and Offshore Security,” 2015, Chapter 6, 106

[26] Vice-Admiral Pradeep Chauhan, “The Indian Navy in the Changing Geopolitics of the Indo-Pacific,” National Maritime Foundation website, 31 August 2023, 1-8, https://maritimeindia.org/the-indian-navy-in-the-changing-geopolitics-of-the-indo-pacific/

[27] Captain Himadri Das, “Ten Years After ‘26/11’: A Paradigm Shift In Maritime Security Governance In India?,” National Maritime Foundation website, 28 November, 2018, https://maritimeindia.org/26-11-a-paradigm-shift-in-maritime-security/#_edn4

[28] Harpal Singh, “Sri Lankan Refugees on March to Delhi,” The Hindu. February 14, 2011. https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/Sri-Lankan-refugees-on-march-to-Delhi/article15444281.ece.

See also: Arun Janardhan, “Explained: The Sri Lankan Refugee Question,” The Indian Express. January 31, 2015. https://indianexpress.com/article/india/india-others/explained-the-sri-lankan-refugee-question/

[29] International Organisation for Migration (IOM), World Migration Report, May 2024, 70, https://publications.iom.int/books/world-migration-report-2024

[30] Global Conflict Tracker, “Global Conflict Tracker.” Council on Foreign Relations, 2024, https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker.

[31] IOM29, “World Migration Report,” 70

[32] IOM29, “World Migration Report,” 70

[33] Adrian Perrera, “Rohingya Refugees and the Shifting Tide in Indonesia,” The Diplomat, January 2024, https://thediplomat.com/2024/01/rohingya-refugees-and-the-shifting-tide-in-indonesia/

[34] The Convention relating to the Status of Refugees came into force in 1951. It evolved in the backdrop of Second World War, and was mainly signed by the European countries. The 1951 Convention for Refugees, and its 1967 Protocol, remain the bedrock of the international refugee regime. The convention evolved in a particular historical-political context and did not account for the historic experiences of countries like India, Bangladesh, Indonesia which are impacted by the IHM in the EIO are neither party nor signatory to the 1951 Convention.

UNHCR India, “States Parties, Including Reservations and Declarations, to the 1951 Refugee Convention,” https://www.unhcr.org/in/about-us/background/1951-convention-relating-status-refugees/.

See also: Ria Kapoor, Making Refugee in India, (Oxford Publications, 2022), 17-94, (for reference to connection between World War Second and the 1951 Refugee Convention)

[35] Mohammed Hussein and Hanna Duggal, “What Is Life Like Inside the World’s Largest Refugee Camp,” Al Jazeera, August 25, 2023. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/longform/2023/8/25/what-is-life-like-inside-the-worlds-largest-refugee-camp.

[36] Perrera,31 “Rohingya Refugee”

[37] Vice Admiral Pradeep Chauhan, “Climate Change,” Lecture Series at the National Maritime Foundation, 08-12 March 2024

[38] Chauhan,35 “Climate Change, Lecture Series at the NMF”

[39] Chime Youdon and Saurabh Thakur, Rising Seas and Coastal Impacts: Metropolitan Resilience in India, (National Maritime Foundation, 2023), 27

[40] ESCAP,9 “The Asia-Pacific Riskscape”

[41] M S Naravane, The Maritime and Coastal Forts of India, (APH Publishing Corporation 1998), 08-123

[42] Naravane,37 “Maritime and Coastal Forts,” 121

[43] David Wheeler, “Quantifying Vulnerability to Climate Change: Implications for Adaptation Assistance,” Centre for Global Development, 2011, 22, https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/1424759_file_Wheeler_Quantifying_Vulnerability_FINAL.pdf

[44] IOM29, Figure 8, “World Migration Report,” 70

[45] Indian Coast Guard (ICG), Gumbo: Nostalgic Recollections of the personnel of the Indian Coast Guard, (ICG Publication). n.d

[46] Cleo Paskal, Global Warring, (Key Porter Publication, 2010), 141

[47] Syed Akbar, “Future Cyclones in Bay of Bengal to Expose 200 Per Cent More Population, Damage: Study,” Times of India, 9 May 2022, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/hyderabad/future-cyclones-in-bay-of-bengal-to-expose-200-per-cent-more-population-damage-study/articleshow/91425586.cms

[48] Image Source: Vice Admiral Pradeep Chauhan, “Climate Change.” Lecture Series at the National Maritime Foundation, 08-12 March 2024

See also: United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), “For Asia-Pacific, Climate Change Poses an ‘Existential Threat’ of Extreme Weather, Worsening Poverty and Risks to Public Health, Says UNDP Report,” n.d.

[49] Chauhan,35 “Climate Change, Lecture Series at the NMF”

[50] Sahana Bose, “Forced Migration Review,” Oxford, Issue 45, 22, February 2014,

https://www.fmreview.org/forced-migration-review

[51] Pushp Bajaj, “Climate Change Risks to India’s Holistic Maritime Security,” National Maritime Foundation Website, 22 June, 2020, https://maritimeindia.org/climate-risks-to-indias-holistic-maritime-security-part-1-rising-sea-level/

[52] S Nanthini, “Global Health Security – Impact of COVID-19: Can Irregular Migrants Cope?” Rajaratnam School of International Studies, 16 April, 2020, https://www.rsis.edu.sg/rsis-publication/nts/global-health-security-impact-of-covid-19-can-irregular-migrants-cope/#.XqJTJ5MzYlU

[53] SAFF, “Climate Migration in South Asia: (Geo)political Challenges and the Quest for Regional Unity,” South Asian Futures Fellowship, April 16 2024, https://www.southasianfuturesfellowship.org/analysis-2/climate-migration-in-south-asia%3a-(geo)political-challenges-and-the-quest-for-regional-unity

[54] Government of Bangladesh, Ministry of Environment and Forests, “National Adaptation Plan of Bangladesh (2023-2050),” Government of Bangladesh, 2023, ii, https://moef.portal.gov.bd/sites/default/files/files/moef.portal.gov.bd/npfblock/903c6d55_3fa3_4d24_a4e1_0611eaa3cb69/National%20Adaptation%20Plan%20of%20Bangladesh%20%282023-2050%29%20%281%29.pdf.

[55] United Nations, “United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS),” 1982, 60 https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf.

[56] UNCLOS,56 60.

[57] UNCLOS,56 29.

[58] UNCLOS,56 40.

[59] UNCLOS,56 53.

[60] UNCLOS,56 99.

[61] United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR), “UNHCR’s Mandate for Refugees and Stateless Persons, and Its Role in IDP Situations,” February 2, 2024. https://emergency.unhcr.org/protection/legal-framework/unhcr%E2%80%99s-mandate-refugees-and-stateless-persons-and-its-role-idp-situations

[62] United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), 2024, https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/index.html.

[63] UNHCR, India, “The Global Compact on Refugees,” https://www.unhcr.org/in/about-unhcr/who-we-are/global-compact-refugees.

[64] Mark Capaldi, Present-Day Migration in Southeast Asia: Evolution, Flows and Migration Dynamics, (Springer Publications, 2023), 1-19.

[65] Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), “Terms of Reference for the ASEAN Humanitarian Assistance Unit (HSU).” n.d. https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/DOC-11-ANNEX-16-Adopted-HSU-TOR-as-of-19-July-2017.pdf.

See also: ASEAN, “ASEAN Convention Against Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children.” n.d https://asean.org/asean-convention-against-trafficking-in-persons-especially-women-and-children/.

See also: ASEAN. “ASEAN Declaration on the Rights of Children in the Context of Migration.” n.d

[66] South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) Secretariat, “Education, Security, and Culture.” n.d https://www.saarc-sec.org/index.php/areas-of-cooperation/education-security-culture.

[67] Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sector Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC), “Sub-Group on Legal and Law Enforcement Issues,” https://bimstec.org/sub-group-on-legal-and-law-enforcement-issues

[68] The Bali Process on People Smuggling, Trafficking in Persons and Related Transnational Crime was established in 2002 as a non-binding, international, multilateral forum to facilitate cooperation and collaboration, information-sharing and policy development on irregular migration in the Asia-Pacific region and beyond. It has 45 member States including India. The four Bali Process Member Organisations are the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), the International Organization for Migration (IOM), the United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime (UNODC) and the International Labour Organization (ILO). Bali Process Working Groups bring together government officials, practitioners and experts from Bali Process Member States and Organisations to progress work around key regional issues and priorities and ensure the Bali Process is responsive to new and emerging challenges.

See: Bali Process, “Regional Consultative Process on People Smuggling, Trafficking in Persons and Related Transnational Crime,” https://www.baliprocess.net/.

[69] Colombo Process (2003) is a Regional Consultative platform addressing the management of overseas employment and contractual labour. It is a non-binding initiative that consists of twelve members including India. The aim of this platform is to promote ‘ethical recruitment’ in major migrant labour-contributing Asian States. The Abu Dhabi Dialogue (ADD) was established in 2008 as a forum for dialogue and cooperation between Asian countries of labour origin and destination. The ADD consists of ten Member States of the Colombo Process (CP), namely Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Nepal, Pakistan, Philippines, Sri Lanka, Thailand and Vietnam; and six Gulf countries of destination: Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, as well as Malaysia. Regular observers include the IOM, ILO (International Labour Organisation), private sector and civil society representatives.

See: Abu Dhabi Dialogue, “A Forum for Dialogue and Cooperation between Asian Countries of Labour Origin and Destination,” http://abudhabidialogue.org.ae/.

[70] BIMSTEC,65 “Subgroup on Law Enforcement,” iii

See Also: Captain Gurpreet Khurana. “BIMSTEC and Maritime Security: Issues, Imperatives and Way Ahead.” National Maritime Foundation, 16 November, 2018, https://maritimeindia.org/bimstec-and-maritime-security-issues-imperatives-and-way-ahead/.

[71] ASEAN, “Adopted Final Review Report of Bohol TIP Work Plan 2017-2020,” 2021,

See also: ASEAN, “Final Version of Bohol TIP Work Plan 2017-2020,” November 13, 2017, https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Final-Version-of-Bohol-TIP-Work-Plan-2017-2020_13Nov2017.pdf.

[72] ASEAN, “ASEAN Multi-Sectoral Work Plan Against Trafficking in Persons 2023-2028 (‘Bohol TIP Work Plan 2.0’),” 2023, https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Adopted-ASEAN-Multi-Sectoral-Work-Plan-Against-TIP-2023-2028-as-of-08-21-23.pdf.

[73] Captain Ranendra Sawan, “Problems and Prospects of Maritime Security Cooperation in the Indian Ocean Region: A Case Study of the Indian Ocean Naval Symposium (IONS),” Sea Power Centre, Royal Australian Navy, Issue 15, 2020, 1-51, https://seapower.navy.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/Soundings_Number_15.pdf

[74] Robert O Keohane and David G. Victor, “The Regime Complex for Climate Change,” Belfer Centre for Science and International Affairs, January 2010, 1-34, https://www.belfercenter.org/sites/default/files/legacy/files/Keohane_Victor_Final_2.pdf.

[75] Keohane and Victor,63 “The Regime Complex.” 4.

[76] Keohane and Victor,63 “The Regime Complex.” 7

[77] Vice Admiral Pradeep Chauhan and Anum Khan, “The Vanilla Islands — Potential for a ‘Pluralistic Security Community.” National Maritime Foundation website, 25 May, 2022, https://maritimeindia.org/the-vanilla-islands-potential-for-a-pluralistic-security-community/.

[78] Captain Himadri Das. Building Partnerships: India and International Cooperation for Maritime Security. (Pentagon Press LLP), 2023, Chapter 4, 81-82.

[79] Captain Himadri Das. Building Partnerships: India and International Cooperation for Maritime Security. (Pentagon Press LLP), 2023, Chapter 3, 50

[80] IORA (Indian Ocean Rim Association), “Signing of MOU Between ASEAN and IORA,” February 2024, Press Release, https://www.iora.int/sites/default/files/2024-02/press-release-signing-mou-asean-iora%20%281%29.pdf.

[81] United Nations, “UN Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime and Its Trafficking in Persons Protocol,” 29 September, 2003, https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/organized-crime/intro/UNTOC.html.

[82] United Nations, “Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC),” 02 September, 1990, https://www.unicef.org/child-rights-convention.

[83] United Nations, “Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW),” 03 September, 1981, https://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/cedaw/.

[84] United Nations, “Global Plan of Action to Combat Trafficking in Persons,” 28 September, 2017, https://www.un.org/pga/72/event-latest/global-plan-of-action-to-combat-trafficking-in-persons/#:~:text=In%20accordance%20with%20GA%20resolution,be%20convened%20on%2027%20%E2%80%93%2028.

[85] Global Compact on Migration, which is an IOM-led initiative, is different from Global Compact on Refugee, led by the UNHCR.

[86] ASEAN, “ASEAN Declaration on the Rights of Children in the Context of Migration,” November 02, 2019, https://asean.org/asean-declaration-on-the-rights-of-children-in-the-context-of-migration/.

[87] ASEAN, “Gender-Sensitive Guidelines for Handling Women Victims of Trafficking in Persons,” 2016, https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Gender-Sensitive-Guidelines-for-Handling-Women-Victims-of-Trafficking-in-Persons-2016.pdf.

[88] S Nathini, “Humanitarian Diplomacy: A Tool to Rebuild Trust in the Humanitarian Sector,” Rajaratnam School of International Studies, March 10, 2023, https://www.rsis.edu.sg/rsis-publication/idss/ip24032-humanitarian-diplomacy-a-tool-to-rebuild-trust-in-the-humanitarian-sector.

[89] Melinda Martinus and Indira Zahra Aridati, “Tackling Technology Abuse and Human Trafficking in ASEAN,” East Asia Forum, February 20, 2024,

[90] Captain Himadri Das, Building Partnerships: India and International Cooperation for Maritime Security. (Pentagon Press LLP), 2023, Chapter 4, 109

[91] Captain Himadri Das, Building Partnerships: India and International Cooperation for Maritime Security, (Pentagon Press LLP), 2023, Chapter 4, 110

[92] Government of Australia, Department of Foreign Affairs, “ASEAN-Australia Counter-Trafficking, “ASEAN-Australia Counter-Trafficking.” 26 January 2023. https://www.aseanact.org/.

[93] ASEAN, “Treaty on Mutual Legal Assistance in Criminal Matters,” 2013

[94] Government of India, Ministry of Defence, “The Annual Joint HADR Exercise, CHAKRAVAT, 2023,” October 9, 2023, Press Information Bureau Press Release, https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1965929#:~:text=The%20exercise%20has%20been%20conducted,09%20to%2011%20Oct%2023.

[95] Vice Admiral Pradeep Chauhan, “Geopolitics.” Lecture Series at the National Maritime Foundation, 28 February-02 March 2024

[96] Embassy of India: Yangon, “India-Myanmar Relationship,” Infrastructure Projects (iv), 2020.

[97] Indian Coast Guard, “SAGAR: Secure Against Geopolitical and Regional Threats,” Indian Coast Guard Newsletter, July 2023. https://indiancoastguard.gov.in/WriteReadData/NewsLetter/202307170941165196861SAGAR2023-3JULY(1).pdf.

See Also: Mullaly,13“Trafficking in Persons Report.” 4

[98] Government of India, Ministry of Defence, “The 39th Edition of Coordinated Patrol Between India and Indonesia,” November 8 2022. Press Information Bureau Press Release, https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1882468#:~:text=The%2039th%20edition%20of,deployment%20briefing%20at%20Belawan%2C%20Indonesia.

It is important to note India and Indonesia conduct Coordinated Patrols (CORPAT) biannually since 2002. In addition to this, the two countries also hold bilateral naval exercises, with the fourth edition taking place in 2023 (SAMUDRA-SHAKTI).

See: Chinmay Mittal, “Difference Between Joint Naval Exercises and Joint Naval Patrolling,” Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, February 10, 2020, https://idsa.in/idsanews/difference-joint-naval-exercises-and-joint-naval-patrolling. (A reference provided to understand the difference between two)

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!