Keywords: Comprehensive Archipelagic Defence Concept; CADC; the Philippines; South China Sea; India

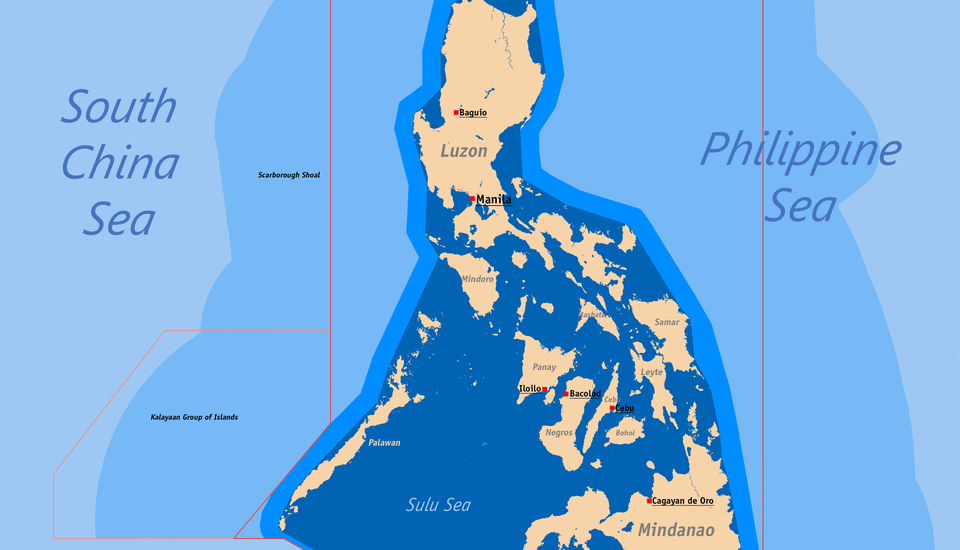

A geopolitical storm has been brewing in the South China Sea (SCS) for some time now, and increasingly, the Philippines finds itself at the centre of this turmoil. Over the past decade, successive administrations of the archipelagic nation have employed various strategies to navigate its often complex and vexed relationship with China in the SCS. These strategies have ranged from diplomacy and economic partnership to hard balancing and leveraging international law. Over time, the Philippines’ strategy has evolved to combine all three approaches to address Chinese assertiveness and violations of international law in the SCS or the West Philippine Sea (WPS).[1] In doing so, the Philippines has adopted an approach distinct from that of its ASEAN counterparts, who have largely relied on diplomacy and negotiations with China. The 2016 Award of the Arbitral Tribunal, which rejected China’s extensive historic claims and criticised its illegal actions in the SCS, marked a pivotal moment in the development of the conflict which provided the support of international law to the arguments of the Philippines. Its latest strategy, encapsulated in the “Comprehensive Archipelagic Defence Concept” (CADC),[2] marks a significant shift in the country’s strategic thinking and defence priorities, moving from an emphasis on internal security— borne out of decades of counterinsurgency efforts— to a focus on comprehensively safeguarding its archipelagic territory, comprising 7,641 islands, along with its sovereign rights in an EEZ spanning approximately 2.2 million square kilometres.

This article analyses the objectives of the CADC and evaluates the existing capacities and capabilities of the Philippines in domains relevant to this strategy. In addition, considering the evolving geopolitical dynamics in the SCS, and the Indo-Pacific at large, it assesses the role of key external players, including the United States (US), Australia, and Japan, in supporting Manila’s efforts to fully operationalise the CADC. Focussing upon India’s growing defence cooperation with the Philippines, it argues that the two nations should harness existing synergies and scale-up cooperation to achieve the rapid and full operationalisation of the CADC, in alignment with other like-minded partners, and concludes by providing policy recommendations to achieve this.

Analysing the Objectives of the Comprehensive Archipelagic Defence Concept (CADC)

The CADC of the Philippines represents a significant shift in that nation’s security strategy, moving from an inward-looking focus to a more maritime-centric approach, with particular emphasis on safeguarding the nation’s resources in its EEZ.[3] This shift was long overdue, given the country’s vast archipelagic geography, and builds on previous service-led initiatives, such as the “Active Archipelagic Defense Strategy” (AADS) introduced by the Philippine Navy in 2013, and the “Archipelagic Coastal Defense” concept published by the Philippine Marine Corps (PMC) in 2021.[4]

This shift was accelerated by the increasing harassment of the Filipino officials and fisherfolk in the WPS by Chinese agencies and, in particular, by the Chinese maritime militia. Obviously, in comparison to China’s substantial naval capacities, the Philippines’ military might at sea is constrained by both limited capacity and corresponding capability. To address this imbalance, the CADC was introduced as a focussed strategy, along with the “Horizon 3” phase of the “Revised Armed Forces of the Philippines Modernisation Programme’ (RAFPMP), to enhance the operational readiness and overall effectiveness the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) in ensuring “unimpeded and peaceful exploration and exploitation of all natural resources within the EEZ” for Filipinos and “those authorised by the Philippine government”.[5] Broadly, fully operationalising the CADC would involve enhancing the AFP’s capacities and capabilities across the following key domains[6]:

- Enhancing Maritime Situational Awareness (MSA). The efforts of the AFP towards generating maritime situational awareness (MSA) are still at a nascent stage. Currently, the Philippines obtains its MSA through a limited number of patrol vessels and aircraft, drones, and information-sharing mechanisms and programmes such as the SeaVision of the US[7] and the Dark Vessel Detection Programme of Canada.[8] In March 2024, the Philippines restructured the National Coast Watch Council (NCWC) to establish the National Maritime Council (NMC) through its “Executive Order (EO) No. 57” so as to develop coordinated policies and strategies focussed on maritime security and MSA/ MDA.[9] Since its establishment, the NMC has been attempting to coordinate the efforts of the Philippine Navy (PN), the Philippine Coast Guard (PCG), and other relevant agencies such as the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (BFAR). It has also conducted training workshops for them on various international information sharing platforms, such as the Indo-Pacific Regional Information Sharing (IORIS) platform under the EU CRIMARIO II project.[10] In addition, Philippines is cooperating with the US through the US-Philippines Space Dialogue to utilise space for developing maritime domain awareness and space situational awareness.[11] However, considering the frequency and scale of Chinese intrusions into the Philippine EEZ, the efforts to generate a “common operating picture” (COP) fall short of the required capacity for the Philippine agencies to track Chinese activity in its waters in real-time and respond rapidly in a unified manner.[12] Further, as confrontations with China increase in the WPS, there is a pressing need for the Philippines to scale-up investment in platforms, equipment, and assets for monitoring and implement the Horizon 3 phase of the RAFPMP in a timely manner, along with forging new partnerships and deepening existing ones with likeminded nations in the Indo-Pacific.

- Bolstering the Maritime and Air Defence (MAD) Capacities and Capabilities of the AFP. Since the preceding decade, the Philippines has been increasing its investment towards improving its maritime defence. In the process, it has inducted three Gregorio Del-Pilar Class offshore patrol vessels (OPVs) (formerly US Hamilton Class cutters) between 2011 and 2016, the BRP Conrad Yap (Pohang Class corvette) in 2019 and two Jose Rizal Class frigates received in 2020 and 2021 from South Korea.[13] Under the Horizon 3 phase of the RAFPMP, the Philippines is to acquire “Wonhae-class Offshore Patrol Vessels (OPVs), missile corvettes, fast attack interdiction boats, and S-70 Black Hawk helicopters.”[14] In October 2023, the Philippine Navy Aviation unit announced its plans to purchase three fixed-wing anti-submarine maritime patrol aircraft.[15] Further, with the delivery of two batches of the shore-based, anti-ship variant of BrahMos missiles from India in April 2024 and 2025, respectively, the maritime defence capacity of the Philippines received a major boost.[16] In respect of air defence, the Philippines currently operates 12 FA-50 fighter jets, purchased from Korea Aerospace Industries (KAI) between 2015 and 2017, and the Philippine Air Force (PAF) recently recommended acquiring an additional twelve FA-50s.[17] While modest in terms of capabilities, these jets are vital for air defence, particularly in securing contested regions of the WPS. Reportedly, the Philippines is seeking to acquire about twenty F-16s from the US, with advanced avionics, radar and weaponry included.[18] In addition, drawing lessons from Ukrainian successes with drones in the Black Sea against Russia, it received the MARTAC MANTAS T-12 unmanned surface vehicles (USVs) from the US to bolster its capacity to conduct asymmetric warfare in the SCS.[19] However, while the CADC envisions greater cooperation amongst the three Services of the AFP, challenges remain in enhancing interoperability amongst the Philippine Army, the Philippine Air Force (PAF), and the Philippine Navy (PN). Consequently, there is a need to regularly conduct joint exercises[20] and train together for eventually conducting multi-domain operations (MDO) to overcome “the incompatibilities in ‘technology’, ‘time’, ‘timing’ and ‘thinking’ amongst all domains.”[21]

- Leveraging strategic partnerships with others in the region, including Australia, Japan, Republic of Korea, and India. Under the CADC, the Philippines is looking to forge deeper strategic ties with other like-minded partner nations across the Indo-Pacific to address the growing military challenges posed by China’s increasing assertiveness in the region.[22] Typifying this is the media-hype given to what is known colloquially (albeit not officially) as the ‘Squad’. This emerged as a strategic response to China’s expanding influence and its aggressive actions in the SCS, as well as its broader efforts to dominate the Indo-Pacific region.[23] The term is seductive enough to have been gleefully picked-up by a few sections of the strategic community, particularly in the Philippines itself and in Australia and is sought to be popularised more widely. The grouping includes the US, Japan, Australia, and the Philippines (but not India)and has conducted combined maritime exercises in the SCS and the Philippine EEZ as part of Manila’s strategic signalling to China.[24] Bilaterally, too, these partner nations are bolstering Philippines’ military capacities and capabilities to defend its rights in the face of China’s strongarm tactics and increasing assertiveness in the Philippine EEZ.

Evaluating the Role of Other Players in Operationalising the CADC

The CADC is reinforced by the Philippines’ strategy of “naming and shaming” China for its coercive actions, implemented under the framework of the “assertive transparency” initiative.[25] This approach has drawn significant domestic and international attention to the persistent challenges the Philippines faces in asserting its sovereign rights within its EEZ. By actively confronting China’s harassment of Filipino officials and fisherfolk, as well as its use of “grey zone” tactics, the Philippines has adopted a markedly different stance from that of most Southeast Asian nations, which have tended to favour diplomacy and negotiation in managing territorial disputes and tensions in the South China Sea. As a result, the Philippines has often found itself isolated within the region in its firm opposition to China’s unlawful activities in the WPS.[26] China has exploited these regional divergences, accusing the Philippines of aligning with a US-led agenda, and frequently portraying it as a cautionary example to deter other ASEAN member States from yielding to what it describes as “Washington’s manipulation” and efforts to sow discord.[27] Consequently, the Philippines has increasingly sought support beyond the region — primarily from its treaty ally, the US, as well as other like-minded partners — to bolster its military capabilities and to uphold both its maritime entitlements and the broader rules-based international order in the South China Sea.

- The United States. The United States remains the principal partner in the Philippines’ military modernisation efforts, providing critical support under the “Mutual Defense Treaty” of 1951. In 2023, under the 2014 “Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement” (EDCA) — which grants US forces access to designated locations within the Philippines[28] — the number of approved sites was nearly doubled and the US committed nearly USD 100 million towards infrastructure upgrades at the existing EDCA sites.[29] Additionally, during the “2+2 Ministerial Dialogue” in July 2024, the US announced a further USD 500 million in military funding for the Philippines.[30] Between 2019 and 2023, the US was also the third-largest arms supplier to the Philippines, following South Korea and Israel.[31] As part of its broader efforts to bolster the capacity of the Philippines to defend its EEZ, the US has provided radar systems[32] and unmanned surface vehicles (USVs),[33] and in 2024, the two allied signed an important intelligence sharing agreement.[34]. Exercise BALIKATAN, the annual joint military exercise between the US and the Philippines, has expanded significantly in recent years. This expansion includes increased participation from partner nations such as Australia, France, and Japan, as well as a broadened scope encompassing multi-domain operations, disaster relief, and cybersecurity.[35] Notably, during the 2023 edition of Exercise BALIKATAN, the “SINKEX Serial” involved the live-fire sinking of a target ship off the coast of Zambales in the SCS.[36] Furthermore, for the first time during the exercise, the US Army deployed a HIMARS (High Mobility Artillery Rocket System) battery from the First “Multi-Domain Task Force” (MDTF). The MDTF also utilised Exercise BALIKATAN to experiment with long-endurance drones, unmanned aerial systems (UAS),[37] and information fusion.[38] These ‘joint-and-combined’ exercises play a pivotal role in operationalising the CADC by enhancing interoperability between the AFP and US Forces.

- Japan. Under the “Maritime Safety Capability Improvement Project” (MSCIP), Japan delivered ten 44-metre Multi-Role Response Vessels (MRRVs) in 2013, followed by two 97-metre MRRVs in 2016. In May 2024, a USD 507 million agreement was finalised for constructing an additional five 97-metre MRRVs, to be funded through an “Official Development Aid” (ODA) loan from the “Japan International Cooperation Agency” (JICA).[39] Between 2016 and 2018, Japan transferred five TC-90 trainer aircraft to the Philippine Navy, one of which was rapidly deployed for patrol missions over the Scarborough Shoal.[40] Since December 2023, Japan’s Mitsubishi Electric Corporation has supplied air surveillance radar systems to the PAF under the Official Security Assistance framework.[41] In a significant development in defence cooperation, a “Reciprocal Access Agreement” (RAA) was signed in July 2024, establishing a legal framework for the enhanced deployment of Japan’s Self-Defense Forces (SDF) in the Philippines. This is the first such agreement Japan has concluded with an Asian country.[42] In addition to participating, since 2023, in successive editions of multilateral Maritime Cooperative Activity (MCA) amongst the ‘Squad’, Japan conducted its first combined military exercise with the Philippines in the SCS in August 2024[43] and became a full-fledged participant in the multilateral Exercise BALIKATAN in April 2025.[44]

- South Korea. As a key Asian defence partner, South Korea was the largest arms supplier to the Philippines between 2019 and 2023.[45] It has provided twelve FA-50 fighter jets, naval platforms, and a range of weapon systems to support the AFP’s modernisation efforts.[46] In 2021 and 2022, Hyundai Heavy Industries (HHI) secured contracts to deliver two corvettes and six offshore patrol vessels (OPVs), scheduled for delivery by 2026 and 2028, respectively.[47] In a key diplomatic milestone, the two nations elevated their relationship to a strategic partnership in October 2024 and signed an agreement to enhance coastguard cooperation.[48] In recent times, South Korea has also articulated a clearer stance on the South China Sea issue, advocating for upholding “the freedom of navigation and overflight based on the principles of international law, including UNCLOS”.[49]

- Australia. The Philippines’ defence partnership with Australia is underpinned by a series of bilateral agreements, including a longstanding Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) on Defence Cooperation (1995), an Australia-Philippines “Status of Visiting Forces Agreement” (2012), an “Enhanced-Defence Cooperation Programme” (E-DCP) (2019), a “Mutual Logistics Support Arrangement”, and an MOU on “Defence Industry Cooperation and Logistics” (2022).[50] The E-DCP, which focuses upon maritime security, counter-terrorism (CT), and humanitarian assistance and disaster relief (HADR), led to the establishment of the “Joint Australian Training Team-Philippines” (JATT-P). This initiative has facilitated training courses and workshops for AFP personnel across all three Services. In August 2023, the two nations also conducted the joint bilateral amphibious exercise ALON.[51] Further, as part of Australia’s capacity-building efforts, a new Air Force facility was donated to the Philippines in 2023.[52]

- Israel. In 2017, the Philippines acquired Spike Extended-Range (ER) missiles from Israel’s Rafael Advanced Defense Systems, for installation on its multi-purpose attack craft (MPAC).[53] Under the Horizon 2 phase of the AFP Modernisation Programme, Israel Shipyards signed a contract in 2021 to deliver nine Shaldag MK V Fast-Attack Interdiction Craft (FAIC), known as the Acero-class in the Philippine Navy.[54] The deal also includes an agreement for the transfer of technology and support for upgrading the Philippine Navy’s shipyard infrastructure,[55] thereby contributing to the Philippine government’s “Self-Reliant Defense Posture” (SRDP) programme.[56] The contract is expected to be fulfilled by June 2025, with the Philippine Navy expressing interest in procuring an additional ten vessels.[57] Furthermore, in July 2023, the Philippines also signed an agreement with Elbit Systems to deliver two long-range patrol aircraft (LRPA) to enhance its aerial surveillance capacities in its EEZ.[58]

CADC and Opportunities Arising for India to Enhance Cooperation with the Philippines

Over the years, India and the Philippines have consistently engaged through various mechanisms including the Joint Defence Cooperation Committee (JDCC), the India-Philippines Maritime Dialogue, Service-to-Service Joint Staff Talks, military training and education programmes, and the Maritime Partnership Exercise (MPX), most recently conducted in 2024.[59] The Philippines also participated in the inaugural ASEAN-India Maritime Exercise (AIME) in 2023 as well as the recent multilateral Exercise MILAN hosted by India in 2024.[60] Furthermore, Indian Navy ships on long-range operational deployments to the Western Pacific Ocean have regularly made port-calls at Manila for over 25 years (Table 1 refers).[61]

|

Table 1: Representative list of Indian Navy Ship visits to the Philippines |

||

| Year | Indian Navy Ships | Other Countries Visited |

| 2014

(August) |

INS Shivalik | Singapore, Vietnam, Malaysia, China, Japan, South Korea |

| 2015

(October) |

INS Sahyadri | Vietnam |

| 2016

(30 May-3 June) |

INS Satpura and INS Kirch | Vietnam |

| 2017

(23 September) |

INS Satpura and INS Kadmatt | Singapore, Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia, South Korea, Japan, Brunei and Russia |

| 2021

(August) |

INS Ranvijay and INS Kora | Vietnam |

| 2023

(02-08 May) |

INS Delhi and INS Satpura | Singapore, Malaysia, Cambodia, Indonesia |

| 2023

(12 December) |

INS Kadmatt | Japan and Thailand |

| 2024

(19-22 May) |

INS Delhi, INS Shakti, and INS Kiltan | Singapore, Malaysia, and Vietnam |

|

Source: Compiled by the author from various sources |

||

The establishment of the CADC as the overarching strategy of the Philippines, alongside its shift from a traditionally land-centric focus to a more holistic approach towards defending its archipelagic territory and maritime zones, presents India with a significant opportunity to enhance maritime security cooperation with the Philippines. The recent delivery of the second batch of BrahMos missiles has further solidified bilateral defence ties and bolstered the coastal defence capacities of the AFP.[62] As the Philippines looks towards like-minded partners such as India to support the Horizon 3 phase of the RAFPMP and the SRDP Programme, the operationalisation of the CADC offers India with a range of avenues to deepen its defence engagement with the Philippines. This partnership would allow both nations to more effectively address the challenge posed by China to the rules-based order in the SCS, and across the wider Indo-Pacific. Given that nearly 55% of Indian trade transits the SCS,[63] India is increasingly asserting its interests in the region, not only as a concerned stakeholder but also to ensure that China’s remains focussed on the SCS issue, away from the Indian Ocean.[64] In a notable shift in its official stance on the escalating conflict in the SCS, India explicitly called for adherence to the 2016 Arbitral Award on the SCS in the Joint Statement of the 5th India-Philippines Joint Commission on Bilateral Cooperation (JCBC),[65] signalling a departure from its earlier neutral and diplomatically cautious stance following the Tribunal’s announcement of the Award in 2016.[66]

Policy Recommendations for India

- Build on the Success of the BrahMos Deal to Strengthen India-Philippines Defence Industrial and Technological Partnerships, Enhancing the AFP’s Maritime and Air Defence Capacities. The USD 375 million BrahMos deal between India and the Philippines has provided a significant boost to bilateral defence cooperation, establishing India as a key actor in the evolving sub-regional geopolitical landscape of the SCS.[67] The Philippines is also expected to procure the Akash short-range surface-to-air missile system in 2025, under a proposed USD 200 million deal. [68] Building on this momentum, India should competitively position itself for future defence projects under the Horizon 3 phase of the RAFPMP, particularly in missile systems and naval platforms, including unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs).

- Donate or Gift a Naval Ship or a Coast Guard Vessel as a Goodwill Gesture: Following the precedent set by the gifting of the active-duty warship, the Kirpan to Vietnam in 2023, India could explore the possibility of extending a similar gesture to the Philippines, through the donation of a naval ship or a coast guard vessel to symbolise deepening strategic goodwill.

- Engage Closely with the “Squad”. While the Philippines has expressed interest in involving India and South Korea in the so-called “Squad”,[69] India should adopt a calibrated approach in assessing the appropriate degree of engagement with this group, which is focussed on security cooperation. However, to avoid being sidelined, India could begin by participating as an observer in the multilateral MCA, conducted by the combined defence forces of the US, Japan, Australia, and the Philippines.

- Pursue the Positioning of an International Liaison Officer (ILO) from the Philippines at the Information Fusion Centre-Indian Ocean Region (IFC-IOR). India and the Philippines should work towards positioning a Philippine ILO at the IFC-IOR to facilitate enhanced information exchange on non-traditional security threats, such as illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing within the Philippines’ EEZ.

- Foster a Close Partnership on Strategic Communications, Public International Maritime Law, and Cooperation within Regional and Multilateral Bodies. India needs to prioritise strategic communications and legal cooperation with the Philippines, focusing on promoting adherence to international maritime law and the rules-based international order. This includes closer bilateral collaboration within regional and multilateral forums, which will be essential to address shared maritime security challenges.

- Explore Opportunities for Joint Hydrocarbon Exploration with the Philippines. Building on ONGC Videsh Ltd’s (OVL) long-standing hydrocarbon exploration activities within Vietnam’s EEZ, OVL should assess the feasibility of joint ventures with the Philippines. With the Malampaya gas field— currently the largest and the only indigenous commercial source of natural gas in the Philippines— projected to depleted of recoverable gas by 2027,[70] Manila is actively seeking new exploration partnerships. The Reed Bank is the only other proven gas reserve of the Philippines but here, contracted survey ships have repeatedly faced Chinese harassment, leading to moratoriums being imposed in 2014 and 2022, although these were later lifted.[71] In this context, India could play a pivotal role as a reliable partner by engaging in joint exploration initiatives in the region with the Philippines.

******

About the Author

Ms Sushmita Sihwag is a Research Associate at the National Maritime Foundation. She holds a master’s degree in liberal studies from Ashoka University, Sonipat, Haryana. Her research focuses upon how India’s own maritime geostrategies are impacted by the maritime geostrategies of ASEAN and its member-states in the Indo-Pacific. She may be contacted at indopac6.nmf@gmail.com

Endnotes:

[1] The Philippine government refers to the part of the South China Sea lying within the Philippines’ EEZ as the “West Philippine Sea” (WPS).

[2] Priam Nepomuceno, “Comprehensive Archipelagic Defense to help PH explore EEZ”, Philippine News Agency, 24 January 2024, https://www.pna.gov.ph/articles/1217527

Also see: “Keynote Address of President Ferdinand R Marcos Jr for the 21st IISS Shangri-La Dialogue”, Presidential Communications Office — PCO, 31 May 2024, https://pco.gov.ph/presidential-speech/keynote-address-of-president-ferdinand-r-marcos-jr-for-the-21st-iiss-shangri-la-dialogue/

[3] Priam Nepomuceno, “‘Comprehensive archipelagic defense’ to help PH explore EEZ”

[4] Rej Cortez Torrecampo, “A Paradigm Shift in the Philippines’ Defense Strategy”, The Diplomat, 03 April 2024, https://thediplomat.com/2024/04/a-paradigm-shift-in-the-philippines-defense-strategy/.

[5] Priam Nepomuceno, “‘Comprehensive archipelagic defense’ to help PH explore EEZ”

[6] Renato Cruz De Castro, “Philippine Imperatives amidst the Resource Scramble in the Indo-Pacific”. Presentation at the Indo-Pacific Regional Dialogue (IPRD), New Delhi, 03 October 2024

[7] Dona Z Pazzibugan, “PH-US tie-up on space tech to help monitor EEZ”, INQUIRER.net, 15 May 2024, https://globalnation.inquirer.net/235921/ph-us-tie-up-on-space-tech-to-help-monitor-eez#.

[8] Joyce Ann L Rocamora, “PH-Canada ink agreement vs. dark vessels”, Philippine News Agency, 14 October 2023, https://www.pna.gov.ph/articles/1211825.

[9] Executive Order No. 57, by the President of the Philippines, The LAWPHIL Project, 25 March 2024, https://lawphil.net/executive/execord/eo2024/eo_57_2024.html.

[10] “Philippine agencies exercise together to consolidate coordination in ensuring safer and more secure seas”, European External Action Service, 29 April 2024, https://www.eeas.europa.eu/delegations/philippines/philippine-agencies-exercise-together-consolidate-coordination-ensuring-safer-and-more-secure-seas_en?s=176.

[11] US Department of State, “Joint Statement on U.S.-Philippines Space Dialogue”, 13 May 2024, https://2021-2025.state.gov/joint-statement-on-u-s-philippines-space-dialogue/.

[12] Jonathan Walberg and Ethan Connell, “How the Philippines Can Counter China’s South China Sea Aggression”, The Diplomat, 23 April 2025, https://thediplomat.com/2025/04/how-the-philippines-can-counter-chinas-south-china-sea-aggression/.

[13] Aaron-Matthew Lariosa, “A Korean Expansion: The Future of the Philippine Fleet”, Naval News, 18 September 2023, https://www.navalnews.com/naval-news/2023/09/a-korean-expansion-the-future-of-the-philippine-fleet/.

[14] “Re-Horizon 3 initiative to spur Philippines defence expenditure”, Asia-Pacific Defence Reporter, 05 March 2024, https://asiapacificdefencereporter.com/re-horizon-3-initiative-to-spur-philippines-defence-expenditure/.

[15] Aaron-Matthew Lariosa, “Philippine Naval Aviation Unveils Modernisation Plans”, Naval News, 19 October 2023, https://www.navalnews.com/naval-news/2023/10/philippine-naval-aviation-unveils-modernization-plans/.

[16] Dinakar Peri, “India delivers first batch of BrahMos to Philippines”, The Hindu, 20 April 2024, https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/india-delivers-first-batch-of-brahmos-to-philippines/article68084161.ece.

[17] Priam Nepomuceno, “PAF recommends acquisition of 12 more S. Korean-made jet fighters”, Philippine News Agency, 06 March 2025, https://www.pna.gov.ph/articles/1245519.

[18] Brad Lendon, “US approves sale of 20 US F-16 fighter jets to Philippines as Washington tightens key Asian alliance”, CNN, 02 April 2025, https://edition.cnn.com/2025/04/02/asia/us-philippines-f16-fighter-jet-sale-intl-hnk-ml/index.html.

[19] Aaron-Matthew Lariosa, “Philippine Navy Receives U.S. Funded USVs for SCS Operations”, Naval News, 19 November 2024, https://www.navalnews.com/naval-news/2024/11/philippine-navy-receives-u-s-funded-usvs-for-scs-operations/.

[20] Priam Nepomuceno, “PH Air Force, Navy boost interoperability via ship deck drills”, Philippine News Agency, 28 February 2025, https://www.pna.gov.ph/articles/1245085.

[21] Tejinder Singh, “Evolution of Multi-Domain Operations and Prospects for Application of Aerospace Power”, Journal of Defence Studies 18, No 1 (January-March 2024): 77, https://www.idsa.in/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/18-1_Tejinder-Singh.pdf.

[22] “Keynote Address of President Ferdinand R Marcos Jr for the 21st IISS Shangri-La Dialogue”

[23] Maria Siow, “New ‘Squad’ bloc could allow Philippines to ‘borrow strength’ of Australia, Japan, US to counter China”, South China Morning Post, 09 May 2024, https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/politics/article/3261905/new-squad-bloc-could-allow-philippines-borrow-strength-australia-japan-us-counter-china.

[24] Department of Defence, Australian Government, “Four nations combine in maritime first”, Australian Government Defence, 08 April 2024, https://www.defence.gov.au/news-events/news/2024-04-08/four-nations-combine-maritime-first.

Also See: Commander of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, “Australia, Japan, New Zealand, Philippines, and United States Conduct Multilateral Maritime Cooperative Activity”, Commander, U.S. Pacific Fleet, 30 September 2024, https://www.cpf.navy.mil/Newsroom/News/Article/3921254/australia-japan-new-zealand-philippines-and-united-states-conduct-multilateral/.

Also See: Department of Defence, Australian Government, “Multilateral maritime cooperative activity”, Australian Government Defence, 06 February 2025, https://www.defence.gov.au/news-events/releases/2025-02-06/multilateral-maritime-cooperative-activity.

[25] Edcel John A Ibarra and Aries A Arugay, “Something Old, Something New: The Philippines’ Transparency Initiative in the South China Sea”, Fulcrum, 06 May 2024, https://fulcrum.sg/something-old-something-new-the-philippines-transparency-initiative-in-the-south-china-sea/.

[26] Laura Zhou, “Help from ASEAN nations to counter China is unlikely: ex-Philippine Navy Officer”, South China Morning Post, 03 December 2024, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/article/3289059/help-asean-nations-counter-china-unlikely-ex-philippine-navy-officer.

[27] Ding Duo, “ASEAN is not a geopolitical tool for the Philippines”, Global Times, 15 October 2024, https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202410/1321236.shtml.

[28] US Department of State, “U.S. Cooperation with the Philippines”, 20 January 2025, https://www.state.gov/u-s-security-cooperation-with-the-philippines/.

[29] “More Than Meets the Eye: Philippine Upgrades at EDCA Sites”, Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative, 12 October 2023, https://amti.csis.org/more-than-meets-the-eye-philippine-upgrades-at-edca-sites/.

[30] Sebastian Strangio, “US Announces $500 Million in Military Funding for the Philippines”, The Diplomat, 31 July 2024, https://thediplomat.com/2024/07/us-announces-500-million-in-military-funding-for-the-philippines/.

[31] Pieter D Wezeman, et al., “Trends in International Arms Transfer, 2023”, SIPRI, March 2024, 6, https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2024-03/fs_2403_at_2023.pdf.

[32] Prashanth Parameswaran, “New Philippines Radar System Spotlights US-ASEAN Maritime Security”, The Diplomat, 29 August 2017, https://thediplomat.com/2017/08/new-philippines-radar-system-spotlights-us-asean-maritime-security/.

[33] Lariosa, “Philippine Navy Receives U.S. Funded USVs for SCS Operations”.

[34] Aaron-Matthew Lariosa, “U.S. and Philippines Sign Intel Treaty, Break Ground on new Command Center”, US Naval Institute, 18 November 2024, https://news.usni.org/2024/11/18/u-s-and-philippines-sign-intel-treaty-break-ground-on-new-command-center.

[35] US Embassy in the Philippines, “Philippine, U.S. Troops To Kick Off Exercise Balikatan 2024”, 17 April 2024, https://ph.usembassy.gov/philippine-u-s-troops-to-kick-off-exercise-balikatan-2024/.

[36] Aaron-Matthew Lariosa, “Kill Chain Tested at First-Ever Balikatan SINKEX”, Naval News, 27 April 2023, https://www.navalnews.com/naval-news/2023/04/kill-chain-tested-at-first-ever-balikatan-sinkex/.

[37] Jen Judson, “US Army experiments with long-endurance drones, balloons in Philippines”, Defense News, 14 May 2024, https://www.defensenews.com/air/2024/05/13/us-army-experiments-with-long-endurance-drones-balloons-in-philippines/.

[38] Madeline Suba, “USARPAC’s first MDTF Advances Interoperability through a Combined US-Philippines Information and Effects Fusion Cell”, US Army, https://www.army.mil/article/266435/usarpacs_first_mdtf_advances_interoperability_through_a_combined_us_philippines_information_and_effects_fusion_cell.

[39] Embassy of Japan in the Philippines, “Signing of the Exchange of Notes for the Maritime Safety Capability Improvement Project for the Philippine Coast Guard (Phase III)”, Embassy of Japan in the Philippines, 17 May 2024, https://www.ph.emb-japan.go.jp/itpr_en/11_000001_01483.html.

[40] Embassy of Japan in the Philippines, “3 JMSDF TC-90s Transferred to the Philippine Navy”, Embassy of Japan in the Philippines, 27 March 2018, https://www.ph.emb-japan.go.jp/itpr_en/00_000509.html.

Also See: Priam Nepomuceno, “Japan-donated plane conducts maritime patrol over Bajo de Masinloc”, Philippine News Agency, 31 January 2018, https://www.pna.gov.ph/articles/1023572.

[41] “Mitsubishi Electric Delivers Mobile Air-surveillance Radar System to the Philippines”, Mitsubishi Electric Corporation, 30 April 2024, https://www.mitsubishielectric.com/news/2024/0430.html.

[42] Mikhail Flores and Karen Lema, “Philippines says pact with Japan takes defence ties to unprecedented high”, Reuters, 08 July 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/philippines-japan-sign-landmark-defence-deal-2024-07-08/.

Also See: Maria Thaemar C Tana, “Japan-Philippines defence deal reflects regional security dynamics”, East Asia Forum, 09 September 2024, https://eastasiaforum.org/2024/09/09/japan-philippines-defence-deal-reflects-regional-security-dynamics/.

[43] “Philippines, Japan militaries hold first joint exercises in South China Sea”, Reuters, 02 August 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/philippines-japan-militaries-hold-first-joint-exercises-south-china-sea-2024-08-02/.

[44] Aaron-Matthew Lariosa, “Japan to Join Balikatan 2025 as Full-Fledged Participant”, Naval News, 30 March 2025, https://www.navalnews.com/naval-news/2025/03/japan-to-join-balikatan-2025-as-full-fledged-participant/.

[45] Wezeman, et al., “Trends in International Arms Transfer, 2023”.

[46] “Philippines, South Korea boost defence cooperation, upgrades ties to strategic partnership”, Reuters, 07 October 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/philippines-south-korea-upgrade-ties-strategic-partnership-2024-10-07/.

Also See: Priam Nepomuceno, “Delivery of primary weapons for Navy frigates set for 2021, 2022”, Philippine News Agency, 30 December 2020, https://www.pna.gov.ph/articles/1125958.

[47] Lariosa, “A Korean Expansion: The Future of the Philippine Fleet”.

[48] “Philippines, South Korea boost defence cooperation, upgrades ties to strategic partnership”.

[49] Yi Wonju, “Korean Embassy voices concerns over Philippine, Chinese vessels collision”, Yonhap News Agency, 07 March 2024, https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20240307005800315.

[50] Australian Embassy in the Philippines, “Australia-Philippines Defence Cooperation”, accessed on 01 April 2025, https://philippines.embassy.gov.au/mnla/Defence.html.

[51] Department of Defence, Australian Government “Philippine and Australian forces embark”, Australian Government Defence, 14 August 2023, https://www.defence.gov.au/news-events/news/2023-08-14/philippine-and-australian-forces-embark.

[52] John Eric Mendoza, “PH gets new Air Force facility from Australia”, INQUIRER.net, 14 March 2023, https://globalnation.inquirer.net/211942/ph-receives-aircraft-facility-from-australia.

[53] Prashanth Parameswaran, “Philippines Gets New Israeli Missile System for its Attach Craft”, The Diplomat, 02 May 2018, https://thediplomat.com/2018/05/philippines-gets-new-israel-missile-system-for-its-attack-craft/.

[54] Jr Ng, “Philippines rolls out first locally assembled Israeli fast attack craft”, Asian Military Review, 21 November 2024, https://www.asianmilitaryreview.com/2024/11/philippines-rolls-out-first-locally-assembled-israeli-fast-attack-craft/.

[55] Jr Ng, “Philippines rolls out first locally assembled Israeli fast attack craft”

[56] “Republic Act No. 12024”, Supreme Court of the Philippines E-Library, 10 October 2024, https://elibrary.judiciary.gov.ph/thebookshelf/showdocs/2/97883.

[57] Aaron-Matthew Lariosa, “Philippine Navy Eyes 10 More Acero Gunboats”, Naval News, 20 February 2025, https://www.navalnews.com/naval-news/2025/02/philippine-navy-eyes-10-more-acero-gunboats/

[58] Frances Mangosing, “PAF to get Israeli-made long-range patrol aircraft”, INQUIRER.net, 12 August 2024, https://globalnation.inquirer.net/245042/paf-to-get-israeli-made-long-range-patrol-aircraft.

[59] Embassy of India in Manila, “Visit of Three Indian Naval (IN) Ships of the Eastern Fleet to Manila, Philippines [19-22 May 2024]”, 22 May 2024, https://www.eoimanila.gov.in/news_letter_detail.php?id=165.

[60] AK Chawla, “MILAN 2024 — the Twelfth Edition”, SP’s Naval Forces, 01 March 2024, https://www.spsnavalforces.com/experts-speak/?id=683&h=MILAN-2024-the-Twelfth-Edition.

[61] Kamlesh Kumar Agnihotri and Nirmal Shankar M, “India’s Outlook Towards South-east Asia and Beyond: ‘Changing Tack’ in Contemporary Environment?”, National Maritime Foundation, 22 August 2023, https://maritimeindia.org/20901-2/#_ftn1.

[62] “India sends second batch of BrahMos missiles to Philippines, strengthening Indo-Pacific Security”, The Economic Times, 21 April 2025, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/defence/india-sends-second-batch-of-brahmos-missiles-to-philippines-strengthening-indo-pacific security/articleshow/120474231.cms?from=mdr.

[63] Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, “Question no. 4832: Indian Trade Through South China Sea”, 01 April 2022, https://www.mea.gov.in/lok-sabha.htm?dtl/35118/question+no+4832+indian+trade+through+south+china+sea.

[64] Gurpreet S Khurana, “The Formation of Indo-Pacific “Squad”: A View from India”, National Maritime Foundation, 06 June 2024, https://maritimeindia.org/the-formation-of-indo-pacific-squad-a-view-from-india/.

[65] Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, “Joint Statement on the 5th India-Philippines Joint

Commission on Bilateral Cooperation”, 29 June 2023, https://www.mea.gov.in/bilateral-documents.htm?dtl/36743/Joint_Statement_on_the_5th_IndiaPhilippines_Joint_Commission_on_Bilateral_Cooperation.

[66] Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, “Statement on Award of Arbitral Tribunal on South China Sea Under Annexure VII of UNCLOS”, 12 July 2016, https://www.mea.gov.in/press-releases.htm?dtl/27019/statement+on+award+of+arbitral+tribunal+on+south+china+sea+under+annexure+vii+of+unclos.

[67] Dinakar Peri, “Philippines envoy hails BrahMos missiles as a ‘game changer’”, The Hindu, 24 June 2024, https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/philippines-envoy-hails-brahmos-missiles-as-a-game-changer/article68328182.ece#.

[68] Shivam Patel, “India expects $200 million missile deal with Philippines this years, sources say”, Reuters, 13 February 2025, https://www.reuters.com/world/india/india-expects-200-million-missile-deal-with-philippines-this-year-sources-say-2025-02-13/.

[69] Sebastian Strangio, “Philippines Wants to Expand ‘Squad’ Grouping to Include India, South Korea”, The Diplomat, 20 March 2025, https://thediplomat.com/2025/03/philippines-wants-to-expand-squad-grouping-to-include-india-south-korea/.

[70] Rodrigo Martinez Picazo and Yasmin Fouladi, APERC Gas Report 2023, Asia Pacific Energy Research Centre, 29 May 2024, 6, https://aperc.or.jp/file/2024/5/29/APERC_Gas_Report_2023_For_Publishing.pdf.

[71] Rhoanne De Guzman and Theresa Martelino-Reyes, “Malacanang lifts moratorium on Recto Bank oil and gas exploration”, VERA Files, 18 July 2024, https://verafiles.org/articles/malacanang-lifts-moratorium-on-recto-bank-oil-and-gas-exploration.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!