Abstract

The European Union (EU) is striving to increase its footprint in the Indo-Pacific as a reliable ‘maritime security provider’. In February of 2022, cognisant of the different outlooks, visions and guidelines promulgated by Australia, ASEAN, Japan, and three EU member-states, namely, France, Germany, and Netherlands, the EU enunciated its Indo-Pacific strategy, entitled the ‘EU Strategy for Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific’ (EUIP). This strategy outlines the EU’s action plans, which will be implemented with like-minded partners in the Indo-Pacific. It delineates the geographical boundaries of the Indo-Pacific region, stretching from the east coast of Africa to the Pacific Islands, almost mirroring India’s definition, which encompasses the oceanic expanse from the east coast of Africa to the western shores of the Americas. The EUIP, when viewed in tandem with the revised ‘EU Maritime Security Strategy’ of March 2023, reveals several commonalities, such as protecting European trade by securing international shipping lanes in the South China Sea, tackling traditional and non-traditional security threats from-, in- and through the sea, improving cyber security, strengthening ocean governance, and maintaining a consensually derived rules-based order. While the Indo-Pacific has become an area of interest for the EU, a major chunk of its maritime security-related missions and programmes are centred upon the Indian Ocean. This paper critically examines the maritime engagements of the EU in the Indian Ocean region; collaborations with Indo-Pacific nations on EUNAVFOR Operation ATALANTA, the concept of the “Coordinated Maritime Presences”, and enhancing Maritime Domain Awareness initiatives/tools between India and the EU.

Keywords: Coordinated Maritime Presences, EUNAVFOR, Indian Ocean Region, Maritime Domain Awareness, IFC-IOR, CRIMARIO, NISHAR, IORIS.

***

This article has a two-fold purpose. First, it seeks to provide readers with baseline information about the EU’s current endeavours and engagements in the IOR, relevant to maritime security. This is an aspect that has received relatively scant attention in contemporary literature, being largely overshadowed by China’s growing prominence and assertiveness in the Indo-Pacific. Secondly, it proposes a set of recommendations for the Government of India which, if adopted, would bolster New Delhi’s approach to the EU within the maritime domain.

Maritime security has been an unwavering priority for nation-states that have interests vested at sea. Foremost among such nations, many of which are pioneers of marine navigation, shipbuilding, and commerce, are the member-states that comprise the European Union (EU). The “European Union Maritime Security Strategy” (EUMSS), which enunciates the EU’s specific maritime interests and the approaches through which it intends to pursue and preserve these interests, was updated in 2023 to better address the maritime security challenges faced by the EU member-states and the broader international community. This strategy emphasises greater cooperation among member-states on the one hand and international partners on the other, in facing challenges such as piracy, maritime terrorism, environmental threats, illegal fishing, etc.

Similar to the EU, India, too, has a rich maritime tradition[1] and a deep-rooted connection with the sea. The Indian Navy articulated India’s maritime security concerns stemming from its maritime interests, through a meticulously formulated strategy document released in 2015. This document, entitled, “Ensuring Secure Seas: Indian Maritime Security Strategy”[2] describes India’s maritime security interests to include the protection of territorial integrity and sovereignty against threats in the maritime environment, ensuring the safety of Indian citizens and goods traversing the maritime domain, as also the resources to be found within the maritime domain, advancing peace, security, and stability in the Maritime Zones of India (MZI) and areas of interest, and preserving national interests in the maritime sphere.[3]

The EU Commissioner for Environment, Oceans and Fisheries, has encapsulated similar objectives of the EUMSS in the following statement,

“The updated MSS will better protect our citizens and promote our blue economy activities and our interests at sea. We will tackle climate change and environmental degradation on maritime security, strengthen maritime surveillance tools, enhance our defences against cyber and hybrid threats, and reinforce the protection of critical maritime infrastructure”.[4]

While significant collaboration exists between India and the EU regarding security matters such as joint efforts on Operation ATALANTA, the ‘EU-India Strategic Partnership: A Roadmap to 2025’[5] nevertheless reveals numerous untapped opportunities. This paper purports to undertake a critical analysis of the EU’s maritime security engagements in the Indian Ocean. Specifically, it focuses upon two key elements of this engagement, namely, (a) naval operational deployments, and (b) information sharing. This paper examines the EU Naval Force (EUNAVFOR) deployments in the Arabian Sea and the Coordinated Maritime Presences (CMPs) in the Indian Ocean. It begins with an examination of the EU’s Operation ATALANTA conducted by EUNAVFOR, evaluating its many accomplishments and a few shortcomings. It also underscores ideological alignments and opportunities for deeper collaboration with the Indian Navy. The concept and mandate of the CMP in the Northwestern Indian Ocean are explored in depth in order to identify areas for cooperation, possibly within a new “Maritime Area of Interest” (MOI) of a future CMP. It also reviews the EU’s information-sharing initiatives in the Indian Ocean region (IOR) and delves into the EU’s Maritime Domain Awareness (MDA) initiatives alongside similar MDA initiatives by India. Finally, the article presents succinct recommendations for India and the EU to consider in the forthcoming stages of their Strategic Partnership.

EUNAVFOR Somalia: EUNAVFOR Operation ATALANTA, EUTM Somalia, and EUCAP Somalia

The European Union Naval Force (EUNAVFOR) Operation ATALANTA holds significance for the EU’s naval diplomacy and the implementation of its “Common Security and Defence Policy” (CSDP) in the north-western segment of the Indo-Pacific. Established in 2008, the operation aims to promote collaboration among EU member-states for the prevention, deterrence and suppression of armed robbery and piracy off the coast of Somalia.[6]

Op ATALANTA, an internationally acknowledged initiative, boasts significant participation from both, national and multi-national military partners, including EU member-state navies, those cooperating with the Combined Maritime Forces (CMF) programmes, and naval forces of Asian partners nations such as India, Japan, South Korea, Russia and China.[7] Noteworthy achievements include the seizure of 15,953 kg of narcotics, the delivery of 3.2 million tonnes of food and aid, the release of 2,628 hostages, the detention of 135 pirate vessels, the protection of 707 “African Union Mission in Somalia” (AMISOM) vessels, and the transfer of 171 pirates to appropriate authorities leading to the conviction of 145 pirates.[8] Op ATALANTA has employed two main approaches, namely, military engagement and information exchange.[9] Participating forces conduct regular checks of vessels in high-risk zones and engage in ‘friendly approaches’ with local seafarers to share ‘Best Management Practices’ (BMP) for protection against piracy, and to monitor fishing activities.[10] The Area of Operations (AoO) of Op ATALANTA is depicted in Figure 1.[11]

Fig 1. European Union Naval Force Somalia – Area of Operations

Source: Outline Map (AoO)- Ministerio De Defensa,

To disrupt and deter piracy and armed robbery, EUNAVFOR warships apprehend pirates based on prior intelligence or sightings reported by Maritime Patrol Aircraft (MPA) and merchant vessels.[12] The “Maritime Security Centre (Horn of Africa)” (MSCHOA) complements these efforts, providing a web-based platform established by the EU in collaboration with the shipping industry to safeguard maritime transport traversing through the Gulf of Aden.[13] The EUNAVFOR has also developed “MERCURY”, an internet-based counter-piracy coordination tool, MERCURY’s ‘Chat Room’ facilitates dialogue amongst the EU, Combined Task Force 151, NATO, the “United Kingdom Maritime Trade Operations” (UKMTO) Centre, and deployed assets from China, Japan, India[14], Russia, Malaysia and Seychelles.[15] Additionally, the EUNAVFOR supports other EU maritime security programmes such as MaSé (Maritime Security)[16] and CRIMARIO (Critical Maritime Routes in the Indian Ocean).[17] The EUNAVFOR has carried out numerous naval interoperability exercises alongside navies throughout the IOR, extensively collaborating with the Indian Navy (IN).

A prominent example of India-EU naval engagements has been the IN-EUNAVFOR anti-piracy operation in the Gulf of Aden on 18-19 June 2021. A total of five warships from four navies — two ships from France and a ship each from India, Italy, and Spain — participated in this operation, which included anti-submarine warfare (ASW) exercises, cross-deck helicopter operations, boarding operations, underway replenishment, and search and rescue (SAR). Most recently, in August 2022, the EUNAVFOR Flagship, the ESPS Numancia, conducted various joint maritime activities with two of the Indian Navy’s frontline guided-missile destroyers, INS Chennai and INS Kochi, in the Gulf of Oman. Subsequently, the EUNAVFOR flagship, ITS Durand de La Penne, exercised with another Indian destroyer, INS Vishakhapatnam, as part of the EU’s strategy for collaboration in the Indo-Pacific.[18] Notably, the IN and EUNAVFOR have also shared common ground on various matters, such as anti-piracy operations, and safeguarding vessels operating under the UN charter of the World Food Programme (WFP).[19]

EUNAVFOR Operation ATALANTA’s renewed mandate consisting of “executive” and “non-executive” tasks are tabulated below: –

|

EUNAVFOR ATALANTA |

|

| EXECUTIVE TASKS | NON-EXECUTIVE TASKS |

| · Protect World Food Programme vessels and other vulnerable vessels. | · Contribute to monitoring drug trafficking, arms trafficking, suspected IUU fishing and illegal charcoal trade in the area of operations using existing means and capabilities. |

| · Detect, prevent, and suppress piracy and armed robbery. | · Contribute to the EU’s integrated approach in Somalia and to all significant activities that help address the root causes of piracy and its networks. |

|

· Contribute to the disruption of drugs and arms trafficking.

|

· Support other EU missions, programmes, and instruments in Somalia such as EUTM Somalia, EUCAP Somalia, EU DEL Somalia and the CMP NWIO. |

| · Contribute to maritime security.

|

· Support the promotion of the overall regional maritime security architecture, all relevant programmes implemented by the commission, and the links developed with the RMIFC (Madagascar) and the RCOC (Seychelles).[20] |

| · Cooperate with Operation AGENOR and develop synergies with the European-led Maritime Situation Monitoring in the Strait of Hormuz / European Maritime Awareness in the Strait of Hormuz (EMASoH) | |

|

Table 1. EUNAVFOR ATALANTA New Mandate Source: EU NAVFOR ATALANTA[21], information tabulated by the author

|

|

To gain a deeper insight into the establishment of EUNAVFOR Somalia, it is crucial to examine the specific programmes and initiatives implemented by the EU in Somalia. In 2010, the “European Union Training Mission” (EUTM) was established to support the Somali National Army (SNA), followed by the launch of a civilian mission, the “European Union Capacity Mission ‘Nestor’” (EUCAP Nestor) which focused on the enhancement of civilian security forces in the Horn of Africa. Following a Strategic Review, EUCAP Nestor was renamed EUCAP Somalia,[22] focusing solely upon activities concerning Somalia’s maritime security authorities and law enforcement agencies.[23] These three missions — Operation ATALANTA, EUTM Somalia, and EUCAP Somalia — all operate within the CSDP framework. However, coordination challenges emerged among these EU initiatives in Somalia due to differing reporting structures. The EUTM encountered challenges in coordinating with non-Western partners involved in advisory and training roles in Somalia, with some SNA members suggesting that the EU-provided training was not on par with that of other programmes.[24] As part of the EU’s integrated approach, the EU Delegation (EU DEL) Somalia, EUNAVFOR ATALANTA, EUTM Somalia, and EUCAP Somalia merged to form ‘EUNAVFOR Somalia’.[25]

Coordinated Maritime Presences (CMP)

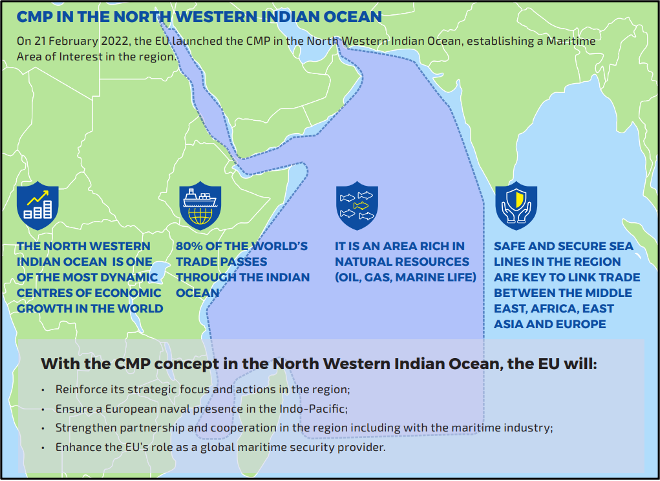

The “Coordinated Maritime Presences” is another operational initiative implemented by the EU. Given the Indo-Pacific’s sensitive geopolitical dynamics, marked by US-China rivalry, it was recognised that EU member-states were likely to deploy naval assets for extended operations in the region.[26] Additionally, ‘freedom of navigation’ remains a significant priority for the EU. Therefore, France advocated a ‘whole-of-EU’ approach via the CMP. This concept also features in the “Strategic Compass”[27] document, which is aimed at enhancing the EU’s defence and security efforts.[28] The CMP’s adaptable approach aims to bolster the EU’s role as a reliable and enduring security partner, aligning with the EUMSS.[29] The pilot case of the CMP in the Gulf of Guinea proved effective, showcasing the EU’s growing role as a regional ‘maritime security provider’.[30]

It is important to note that the CMP is not a CSDP mission or a planned operation; it is instead, an ad hoc[31] coordination on a voluntary basis, with assets displaying the EU flag but remaining under their respective national chains of command.[32] It is likewise important to acknowledge that EU member-states have a significant presence in the IOR through their national assets, aligned with their respective national strategies. Their naval activities serve national interests in areas of concern that are also pertinent to the EU. The EU anticipates that the CMP as a tool will enhance coordination among naval deployments from member-states, ensuring a prominent EU maritime presence in the chosen ‘Maritime area of Interest’ (MAI), that is, the Northwestern Indian Ocean (NWIO). This will be done by the creation of a ‘Maritime Area of Interest Coordination Cell’ (MAICC) which will facilitate member-states to share data (situational information) collected while sailing within the MAI. This would enable a continual collection of data pertaining to the specified MAI flexibly and economically.[33]

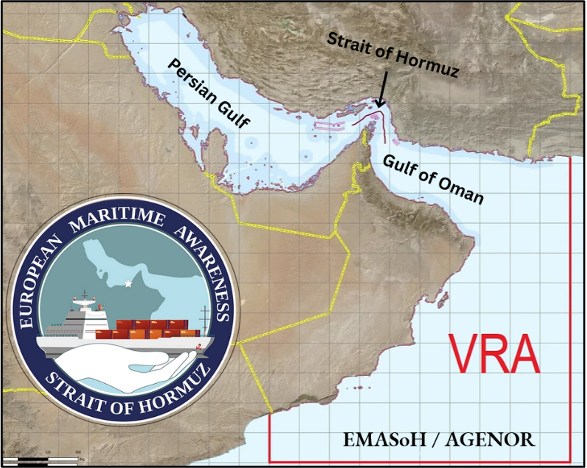

The EU’s area of maritime interest in the NWIO encompasses two critical chokepoints, namely, the Strait of Hormuz and the Strait of Bab-El Mandeb. In the Gulf of Oman, the EU established the ‘European Maritime Awareness in the Strait of Hormuz’ (EMASoH) in January 2020. Operation AGENOR, the military track of EMASoH, involves assets from Germany, Belgium, Denmark, Greece, France, Italy, Netherlands, and Portugal, as well as Norway (a non-EU member-state).[34] The Voluntary Reporting Area (VRA) for EMASoH is depicted in Figure 2.[35] EMASoH fosters collaboration among these nations to establish a unified strategic approach aimed at de-escalating tensions in the Persian Gulf region, particularly, between Iran and its adversaries.[36]

Fig 2. The Area of Interest of EMASoH,

Source: EMASoH, Annotations by the author

One could posit that the selection of the NWIO as a new MAI, stems from the EU’s pre-established naval missions and maritime competencies gained through initiatives such as EUNAVFOR Op ATALANTA and the European Maritime Awareness in the Strait of Hormuz or EMASoH.[37] The NWIO MAI is depicted in Figure 3.[38]

Fig 3. CMP in the NWIO

Source: CMP Factsheet

Another example of naval cooperation between India and the EU took place within the paradigm of the CMP. In June 2021, the IN, and the assets of the EUNAVFOR conducted exercises in the Gulf of Aden, featuring five warships from four different nations: India’s INS Trikand, Italy’s ITS Carabinere, Spain’s ESPS Navarra and France’s FS Tonnere and FS Surcouf.[39]

Additionally, Germany dispatched its frigate FGS Bayern to the Indo-Pacific in August 2021 for a six-month deployment, engaging in Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPS) in international waters. FSG Bayern also participated in the Maritime Partnership Exercise in the Gulf with the Indian Navy for Anti-piracy Operations.[40] Warships from Denmark, Italy, the Netherlands, and Germany are expected to visit South and Southeast Asia in 2024, and port calls in India are very likely.[41] While Greece, Spain and Portugal could play larger roles in the Indo-Pacific, budget constraints, particularly due to the focus on the Russia-Ukraine conflict, make this scenario unlikely.

Maritime Domain Awareness (MDA) Tools of EU and India

The EU’s maritime operational deployments require significant Maritime Domain Awareness (MDA) by way of information-sharing networks. The following segment will outline the MDA initiatives and tools of the EU. Subsequently, the section will also delve into India’s own “Information Fusion Centre – Indian Ocean Region” (IFC-IOR), and the development of the MITRA-NISHAR fusion software.

EU’s MDA Initiatives and Tools. The EU’s “Critical Maritime Routes” (CMR) programme, operating as an “Instrument for Stability” (IfS),[42] was established to combat piracy and promote information-sharing in the Horn of Africa and Southeast Asia.[43] Another EU-funded project, the “Critical Maritime Routes Monitoring, Support and Evaluation Mechanism” (CRIMSON), coordinates CMR initiatives such as the “Critical Maritime Routes in the Indian Ocean” (CRIMARIO)[44] programme launched in 2015.

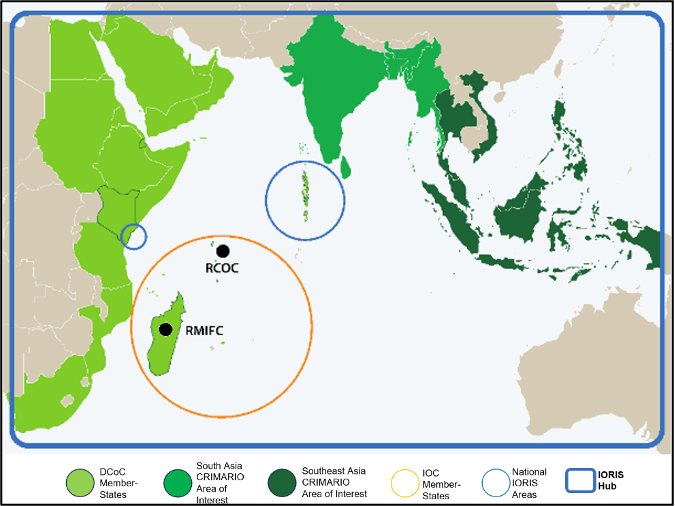

- CRIMARIO aims to enhance MDA and maritime safety in the northern segment of the Western Indian Ocean by establishing information-sharing infrastructures, enhancing law enforcement capacities for vulnerable nations, and strengthening inter-agency cooperation in maritime surveillance.[45] CRIMARIO also provides comprehensive training and capacity-building programmes. Maritime data processing courses using IORIS were conducted with Kenya, Madagascar, Comoros, Seychelles, and Mauritius.[46] CRIMARIO’s mandate ended in 2019. It is important to note that while CRIMARIO remains funded by the EU, it does not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the EU; CRIMARIO is managed by civilian staff and there is relatively little military involvement.[47]

- CRIMARIO II. CRIMARIO’s mandate was extended in 2020 and renamed “CRIMARIO-II”. The latter sought to build upon the experience of its initial phase, broadening its area of interest to now encompass the waters of South and Southeast Asia. In 2022, CRIMARIO II’s geographical scope covered the Indo-Pacific region.[48] CRIMARIO II seeks to focus upon enhancing cooperation and synergies among various information-sharing entities. These include Regional Information Fusion Centres, National Maritime Operation Centres, National Maritime Information Sharing Centres, Joint Operations Centres, and several regional organisations (see Figure 4). Additionally, third-party nations, including EU member-states, and partners such as Japan, the USA, and Australia, are also involved.[49] CRIMARIO II has achieved significant milestones, such as deploying the IORIS platform in a variety of maritime exercises. These exercises took place between France and the Philippines in March 2023, as well as during the Philippines interagency exercise in August and November of 2023. IORIS was also utilised during the Pacific Island Exercises in March of 2023 and the IONS exercise in November of that year. Additionally, CRIMARIO’s training programme has been implemented in Thailand, the Pacific Islands (Pacific Fusion Centre), and South Africa.[50] To enhance Maritime Situational Awareness (MSA) in the Western Indian Ocean, the EUNAVFOR Op ATALANTA and CRIMARIO signed a collaborative agreement to exchange information and data via the IORIS platform.[51]

Fig 4. CRIMARIO II’s collaboration with various regional organisations in the Indo-Pacific

Fig 4. CRIMARIO II’s collaboration with various regional organisations in the Indo-Pacific

L-R: Indian Ocean Naval Symposium (IONS), Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA), Djibouti Code of Conduct (DCoC), Regional Cooperation Agreement on Combating Piracy and Armed Robbery against Ships in Asia (ReCAAP), International Maritime

Source: Collated by the author

- IORIS. IORIS is a non-military maritime coordination and information-sharing tool, which caters to national and regional multi-agency needs. It operates as a secure web-based platform, facilitating joint planning and coordination of maritime operations, including crisis- and incident-management.[52] This tool is adaptable to the specific needs of the centre/organisation using it, offering features such as geographic displays, Automatic Identification System (AIS) data, and communication facilitation. Currently, over 50 national and regional maritime agencies from 23 nations in the Indo-Pacific utilise IORIS.[53] The IORIS community areas are depicted in Figure 5.

Fig 5. IORIS Community Areas

Source: Image from Mr Martin Cauchi-Inglott’s presentation on IORIS, at the 2021 edition of the Indo-Pacific Regional Dialogue (IPRD-2021)

- IT. SHARE.IT is an interoperability framework that seeks to enable selective information exchange among different Maritime Fusion Centres. The EU projects it as the crucial missing link for Maritime Situational Awareness (MSA) in the Indian Ocean and beyond.[54] Information Fusion Centres, such as IFC Singapore, RMIFC Madagascar, etc., collaborate every six months to address developmental challenges and ensure confidentiality, integrity, and sustainability of data protection.[55] The recent 3rd SHARE.IT interoperability conference in Bangkok gathered over 48 directors and experts from various regional and national Information Sharing Centres in the Indo-Pacific.[56] VAdm Pradeep Chauhan, the Director-General of the National Maritime Foundation, participated in the 3rd SHARE.IT Interoperability Conference (see Figure 6), and opined that India would plug-in its own non-military MDA software into the SHARE.IT platform once the SHARE.IT stakeholders had co-developed and tested the platform.[57]

Fig 6. VAdm Pradeep Chauhan, DG NMF, at the 3rd SHARE.IT Interoperability Conference in Bangkok

Source: CRIMARIO II

India’s MDA Capabilities

The MDA initiatives and tools of India are as follows:

- IFC-IOR. The “Information Fusion Centre – Indian Ocean Region” (IFC-IOR) was established by the Indian Navy in 2018. Despite its geographically restrictive name, the IFC-IOR seeks to address maritime security challenges across the wider Indo-Pacific, through a mix of national and collaborative approaches. It acts as an information-sharing hub[58] that uses the indigenously developed “Merchant Ship Information System” (MSIS) to develop a ‘Common Operation Picture’ (COP) for information exchange and has over 67 linkages in 25 countries. There are (as of early-2024) 13 ‘International Liaison Officers’[59] (ILOs) positioned within the IFC-IOR, which enables them to identify, track, and monitor developments in the maritime domain well beyond just the IOR (see Figure 7).[60]

Fig 7. The 13 International Liaison Officers in the IFC-IOR (as of early-2024) are from Australia, Bangladesh, France, Italy, Japan, Mauritius, Maldives, Myanmar, Seychelles, Singapore, Sri Lanka, the UK, and the USA.

Source: Image collated by the author.

- MITRA-NISHAR. To achieve interoperability amongst ‘friendly foreign countries’ (FFCs), the Indian Navy has developed a communication platform called the MITRA Terminal, which utilises the NISHAR (Network for Information Sharing) application. MITRA-NISHAR (see Figure 8)[61] was inaugurated by Shri Rajanth Singh, the Hon’ble Defence Minister of India during MILAN 2024, a naval exercise conducted by the Indian Navy in and off the port-city of Vishakhapatnam, for friendly navies.[62] The primary goal of NISHAR is to enable FFCs to strategically monitor and safeguard their maritime environments with precision through information exchange at the tactical level. NISHAR serves as a secure and encrypted web and satellite-based tool, facilitating real-time communication through the creation of a COP. This COP is generated by consolidating AIS and radar tracks, Maritime Safety Information System (MSIS) feeds, and Internet Query Services, thereby, enhancing the overall COP for maritime situational awareness (MSA).[63]

Fig 8. NISHAR communication link and MITRA Terminal launched at MILAN 2024

Fig 8. NISHAR communication link and MITRA Terminal launched at MILAN 2024

Source: NewsAIDN

- While the CRIMARIO-II team is at pains to project CRIMARIO-II as public goods applicable in the maritime common, this projection begs the question of whom these ‘critical maritime routes of the Indian Ocean’ are “critical” for. If the answer is that they are critical for the EU and its member States but not necessarily for every other State outside of the EU, then CRIMARIO-II is as much an ‘influence building’ tool as any other. It is, consequently worrying to find that a few European Union External Action Service (EEAS) representatives perceive NISHAR as a direct competitor of IORIS; they question NISHAR’s client base, its technological uniqueness, and its sustainability.[64] If the EU and India continue to pursue their respective agendas in the Indo-Pacific regarding MDA, the environment may become competitive rather than cooperative. When comparing the mandates of CRIMARIO[65] and CRIMARIO II[66], it certainly appears that the EU is attempting to expand its own influence beyond the Indian Ocean; the focus area of these programmes has progressively shifted eastwards[67] and now has reached the Strait of Malacca. That having been said, it must be admitted that he EU’s simple demand and supply model of MDA tools, in terms of IfS has given it a significant advantage in the Indian Ocean.[68]

Way Ahead for India and the EU

India has often been perceived to be the ‘preferred security partner’[69] and ‘first responder’ in situations of crisis; relief operations undertaken in the wake of natural disasters, non-combatant evacuation operations, counter-piracy missions, search and rescue missions, post-conflict relief missions, capacity-building missions, and financial assistance.[70] Through its maritime policy of Security and Growth for All in the Region (SAGAR), India has focused upon the security and safety of its trade, energy, shipping, assets, fishing and resources in the maritime domain, while strengthening ties with its maritime neighbours on these very subjects and, in addition, on issues such as maritime security capability-enhancement, infrastructural development, information-exchange, etc.[71] The EU needs to understand and address the requirements and security concerns of the Indian Ocean countries without imposing its agenda (howsoever subtly) when engaging with them.

Given that the mandates of several EU programmes — including CRIMARIO II and the CMP NWIO — are concluding this year, and with the mandate of the EU-India Strategic Partnership: Roadmap due to end next year, this is an opportune moment for the India and EU to consider the recommendations set forth in the succeeding paragraph.

Policy recommendations

(1) While the EU has several ongoing collaborative programmes in the IOR and often conducts joint operations and/or exercises, it could be advantageous for it to adopt a training approach that is not so much a “teacher-and-pupil” model but rather, one that recognises and utilises the experiential strengths of its regional participants in addressing maritime security challenges such as piracy and lack of safety at sea — perhaps a more “collaborative” model, thereby maintaining a more ‘comprehensive’ maritime security architecture. This is especially crucial in the western segment of the Indo-Pacific, namely, the Indian Ocean and its fringing seas.

(2) The EU, working in close collaboration with India and the Indian Ocean Naval Symposium (IONS), could benefit from the initiation of truly-combined training sessions and operational planning processes for the benefit of member-States of the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA), Djibouti Code of Conduct (DCoC), the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC), and even the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Shared expertise in implementing such activities in areas of mutual interest would enhance cooperation between India and the EU.

(3) The CMP could be more than merely a coordination concept for the EU navies. For the EU and its member-states to integrate further into the Indo-Pacific, the CMP may be used to project the EU as a reliable “maritime security partner” rather than the stated (overly grandiose) aim of becoming a ‘global security provider’.

(4) If India can, indeed, be coopted as a trusted partner, the next MAI (and perhaps the next CMP) could include the Bay of Bengal region, in line with the strategic objectives of the EUMSS.[72] It would be best if this was to result from a combined EU-India-BIMSTEC gradual effort rather than countries concerned being presented with a fait accompli that would almost certainly raise suspicion and breed resentment.

(5) Additionally, the mandate of the next CMP could facilitate an increase in military-to-military connections with several member-States and partners within the Indo-Pacific, allowing for pre-planned naval exercises, port visits, and information exchange. This presents opportunities to strengthen naval engagements with key allies like India, Japan, South Korea, Indonesia, and the Philippines.[73]

(6) India and the EU could utilise their respective Track 1.5 & Track 2 institutions to flesh-out Track 1 engagements on issues such as non-traditional security threats (e.g., piracy, armed robbery, lawfare, hybrid-and cyber-attacks, illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing (IUUF), etc.) whenever warships of EU member-States make a port call in India.

Operational Recommendations

(1) The Indian Navy should leverage the forthcoming deployments to South and Southeast Asia by warships of EU member-States by organising informal MDA/MSA workshops and introducing MITRA-NISHAR.

(2) An EU representative urgently needs to be nominated as an ILO in the IFC-IOR. This will enhance MDA, expertise development, and coordination of the activities of the multiple stakeholders within the maritime areas of common interest to the EU and India.

(3) India and the EU share similar ideologies on neighbourhood cooperation, and both have deployed naval assets in the Horn of Africa, the Gulf of Oman, and the Red Sea, for the same purpose. The Indian Navy could take the lead for the conduct of combined interoperability exercises with such navies, utilising MITRA-NISHAR, thereby also creating ample opportunities for Track 1 dialogue.

(4) Twelve Indian Naval ships[74] and warships of EU member-States (under the EUNAVFOR Op ASPIDES)[75] were separately deployed in early 2024 in the Red Sea to protect merchant vessels against ongoing Houthi attacks. It is clear that the opportunity for the EU and the India to mount at least coordinated if not combined operations was not seized. Together, the IN and the navies of the EU member states could explore interoperability mechanisms in the Red Sea to augment collaborative efforts, possibly facilitated through the use of NISHAR.

(5) Similarly, Op SANKALP[76] and EMASoH Op AGENOR are internationally recognised operations deployed by India and the EU respectively, in the Gulf of Oman. Information concerning merchant vessels transiting the Strait of Hormuz and possible changes in their sailing behaviour could be shared, thereby, enhancing naval cooperation.

Conclusion

The evolving landscape of maritime security demands robust strategies and collaborative efforts from nation-states and international organisations alike. Both the EU and India have demonstrated a commitment to safeguarding their maritime interests through comprehensive strategies such as the EUMSS and the Indian Maritime Security Strategy. However, there remains untapped potential for deeper cooperation, as detailed in this article. By leveraging information sharing and exploring naval and maritime cooperation in areas of mutual interest, India, and the EU can enhance the extant maritime security architecture, safeguard their national economic interests, and address collaboratively emerging challenges in the maritime domain. Towards these ends, implementation of the recommendations outlined in this analysis can further strengthen the strategic partnership and contribute to a safer and more secure maritime environment.

******

About the Author

Ms Saaz Lahiri is a Research Associate at the National Maritime Foundation (NMF). She holds a Bachelor’s degree in ‘History and International Relations’, and a Post Graduate Diploma in ‘International Relations’ from Ashoka University. Her research focuses upon the manner in which India’s maritime strategies interface and interact with those of the European Union (EU). She can be reached at eu4.nmf@gmail.com.

Endnotes:

[1] Capt Ranendra Singh Sawan, “India’s Maritime Identity”, https://maritimeindia.org/indias-maritime-identity/

[2] Cmde Sanjay J Singh, Cdr Sarabjeet S Parmar, and Cdr Jasneet S Sachdeva, eds., “Ensuring Secure Seas: Indian Maritime Security Strategy”, https://bharatshakti.in/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Indian_Maritime_Security_Strategy_Document_25Jan16.pdf

[3] Capt Sarabjeet S Parmar, “National Perspectives: India’s Maritime Outlook”, https://maritimeindia.org/national-perspectives-indias-maritime-outlook/

[4] Commissioner Virgunijus Sinkevicius, “Maritime Security: EU updates Strategy to Safeguard Maritime Domain against New Threats”, European Commission Press Release of 10 March 2023, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_23_1483

[5] “EU-India Strategic Partnership: A Roadmap to 2025”, EEAS, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/45026/eu-india-roadmap-2025.pdf

[6]“Operation ATALANTA Booklet,” European Union Naval Force Somalia: Operation ATALANTA, https://eunavfor.eu/sites/default/files/2021-09/20190520_A4-booklet-1_EU-U.pdf

[7] Ibid

See Also: “Mission”, EU Naval Force Operation ATALANTA, accessed 20 January 2024, https://eunavfor.eu/mission

[8] “Key Facts and Figures”, EU NAVFOR ATALANTA, https://eunavfor.eu/key-facts-and-figures

[9] Dr Christian Kaunert et al, “Somalia versus ‘Hook’: Assessing the EU’s Security Actorness in Countering Piracy off the Horn of Africa,” Cambridge Review of International Affairs, 27:3, p 600

[10] https://eunavfor.eu/sites/default/files/2021-09/20190520_A4-booklet-1_EU-U.pdf

[11] “EU NAVFOR – ATALANTA Operation: European Union Maritime Security Provider”, Ministerio De Defensa (Ministry of Defence – Spain), Mandate, https://emad.defensa.gob.es/en/operaciones/operaciones-en-el-exterior/42-ATALANTA/index.html?__locale=en

[12] “Mission”, EU Naval Force Operation ATALANTA, accessed 20 January 2024, https://eunavfor.eu/mission

[13] Kaunert, “Somalia Versus ‘Hook’”, 600.

[14] “MSCHOA and Maritime Domain Awareness. How?”, Maritime Security Centre Horn of Africa, https://on-shore.mschoa.org/mschoa-and-maritime-domain-awareness-how/#MSCHOA

[15] Kaunert, “Somalia Versus ‘Hook’”, 601.

[16] Programme to promote Regional Maritime Security (MASE)

See Also:

“Programme to Promote Regional Maritime Security”, EEAS, published 18 August 2016, https://www.eeas.europa.eu/node/8407_en

[17] “ European Union Naval Force Somalia Operation ATALANTA”, EUNAVFOR, Information Booklet, https://eunavfor.eu/sites/default/files/2021-09/20190520_A4-booklet-1_EU-U.pdf

[18] “Operation ATALANTA Joint Activity with India”, EEAS, 10 August 2023, https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/operation-atalanta-joint-activity-india_en#:~:text=The%20European%20Union%20Naval%20Force,cooperation%20in%20the%20Indo%2DPacific.

[19] “Maiden Indian Navy – European Union Naval Force (EUNAVFOR) Exercise in the Gulf of Aden”, Press Information Bureau Delhi, Ministry of Defence, 18 Jun 2021, https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1728276

[20] “EU Naval Force Operation ATALANTA: Mission”, https://eunavfor.eu/mission

[21] Ibid.

See Also: Ministerio De Defensa (Ministry of Defence – Spain), Mandate, “EU NAVFOR – ATALANTA Operation: European Union Maritime Security Provider”, https://emad.defensa.gob.es/en/operaciones/operaciones-en-el-exterior/42-ATALANTA/index.html?__locale=en

[22] “EUTM Somalia: European Union Training Mission in Somalia – Military Mission,” EEAS, EUTM Somalia, 30 November 2020, https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eutm-somalia/eutm-somalia-european-union-training-mission-somalia-military-mission_und_fr?s=340

[23] “EUCAP Somalia: European Union Capacity Mission in Somalia – Civilian Mission”, EEAS, 30 November 2020, EUCAP Somalia: European Union Capacity Building Mission in Somalia – Civilian Mission | EEAS (europa.eu)

[24] Paul D. Williams et al, “The European Union Training Mission in Somalia: An Assessment”, SIPRI (December 2020) p 15, https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2021-02/bp_2011_eutm_somalia_3.pdf,

[25] EEAS, “EUCAP Somalia: European Union Capacity Mission in Somalia” https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eucap-som_en?s=332#

[26] “Maritime Security: Council Approves Revised EU Strategy and Action Plan”, Council of EU, Press Release, 24 October 2023, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2023/10/24/maritime-security-council-approves-revised-eu-strategy-and-action-plan/

[27] “Strategic Compass Factsheet,” EEAS, March 2023, Security Compass (europa.eu)

[28] Nováky, N, “The Coordinated Maritime Presences Concept and the EU’s Naval Ambitions in the Indo-Pacific,” European View (2022), https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/17816858221089871

[29] “Maritime Diplomacy: How Coordinated Maritime Presences Serve EU Interest Globally,” EEAS, 22 August 2022, https://www.eeas.europa.eu/node/416828_es?s=248

[30] “Coordinated Maritime Presences: Council Extends Implementation in the Gulf of Guinea for 2 years and Establishes a New Concept in the North-West Indian Ocean”, European Council & Council of the European Union, 21 February 2022, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2022/02/21/coordinated-maritime-presences-council-extends-implementation-in-the-gulf-of-guinea-for-2-years-and-establishes-a-new-concept-in-the-north-west-indian-ocean/

[31] Coordinated by the Senior Coordinator of the CMP.

[32] “Coordinated Maritime Presences,” EEAS, 03 December 2021, https://www.eszxxzzxxeas.europa.eu/eeas/coordinated-maritime-presences_en

[33] “Maritime Diplomacy: How Coordinated Maritime Presences (CMP) Serves EU Interest Globally”, EEAS, 22 July 2022, https://www.eeas.europa.eu/node/416828_es?s=248

[34] “European Maritime Awareness in the Strait of Hormuz,” EMASoH, Home | EMASoH (emasoh-agenor.org)

[35] “EMASoH/AGENOR”, EMASoH, About | EMASoH (emasoh-agenor.org)

[36] Ibid

[37] “How Coordinated Maritime Presences Serve EU Interest Globally,” EEAS, 22 August 2022, https://www.eeas.europa.eu/node/416828_es?s=248

[38] “Coordinated Maritime Presences Factsheet”, EEAS, March 2022, Security Compass (europa.eu)

[39] Moksh Suri, “Explaining EU Maritime Security Cooperation Through the Coordinated Maritime Presences Tool,” Finabel – The European Army Interoperability Centre, January 2023.

[40] “INS Trikand undertakes Maritime Partnership Exercise with German Navy Ship,” Ministry of Defence, Government of India, Press Information Bureau, 28 August 2021, https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1749945

[41] Discussion with an EEAS high representative, European Union Visitors Programme, Brussels, November 2023.

[42] IfS is the primary tool of the EU to tackle the intersection between security and development. This instrument is mandated and policy-flexible; it is chiefly employed to provide crisis management funding assistance to nations in turmoil.

[43] Kaunert, “Somalia Versus ‘Hook’”, 602.

[44] “EU Maritime Security Programming: A Mapping and Technical Review of Past and Present EU Initiatives,” RUSI Europe, European Commission, CRIMSON II, Royal United Servies Institute, https://rusieurope.eu/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/EU-Maritime-Security-Programming.pdf

[45] “CRIMARIO, Critical Maritime Routes Indo-Pacific,” EU Indian Ocean Region South & Southeast Asia, https://crimario.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/210920-Crimario-factsheet-EN-final.pdf

[46] “EU Maritime Security Programming: A Mapping and Technical Review of Past and Present EU Initiatives,” RUSI Europe, European Commission, CRIMSON II, Royal United Servies Institute, https://rusieurope.eu/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/EU-Maritime-Security-Programming.pdf

[47] In conversation with representatives from CRIMARIO II in May 2023 in Brussels.

[48] “CRIMARIO – Critical Maritime Routes Indo-Pacific”, Service for Foreign Policy Instruments, European Commission, https://fpi.ec.europa.eu/projects/crimario-critical-maritime-routes-indo-pacific_en

[49] “Mission and Objectives”, CRIMARIO II: Interconnecting the Indo-Pacific, https://www.crimario.eu/mission-and-objectives/.

See Also:

“CRIMARIO, Critical Maritime Routes Indo-Pacific,” EU Indian Ocean Region South & Southeast Asia, https://crimario.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/210920-Crimario-factsheet-EN-final.pdf”

[50] “CRIMARIO at the Indo-Pacific Ministerial Forum”, CRIMARIO II, 06 February 2023, https://www.crimario.eu/crimario-at-the-indo-pacific-ministerial-forum/

[51] “EUNAVFOR Operation ATALANTA and CRIMARIO Sign a Collaborative Agreement Concerning the Use of the Indo-Pacific Regional Information Sharing (IORIS) Platform”, CRIMARIO II, 31 August 2023, https://www.crimario.eu/eunavfor-atalanta-and-crimario-ii-sign-a-collaborative-agreement-concerning/#:

[52] “IORIS: The Maritime Operational Coordination & Communications Platform for the Indo-Pacific,” CRIMARIO II, https://www.crimario.eu/ioris-the-maritime-operational-coordination-communications-platform-for-the-indo-pacific/

[53] Ibid

[54] “Third SHARE.IT Interoperability Conference: Presenting the Latest Technological Developments and Formalising the Community to Strengthening Maritime Security through Fast Communications,” CRIMARIO II, 25 November 2023, https://www.crimario.eu/third-share-it-interoperability-conference-presenting-the-latest-technological-developments-and-formalising-the-community-to-strengthening-maritime-security-through-fast-communication/

[55] “SHARE-IT Interoperability framework for Maritime Situational Awareness,” CRIMARIO, https://www.crimario.eu/share-it/.

[56]“Third SHARE.IT Interoperability Conference: Presenting the Latest Technological Developments and Formalising the Community to Strengthening Maritime Security through Fast Communications,” CRIMARIO II, 25 November 2023, https://www.crimario.eu/third-share-it-interoperability-conference-presenting-the-latest-technological-developments-and-formalising-the-community-to-strengthening-maritime-security-through-fast-communication/

[57] VAdm Pradeep Chauhan, Director-General National Maritime Foundation, Discussions with the Author, 21 March 2024

[58] Captain Himadri Das, “Maritime Domain Awareness in India: Shifting Paradigms”, National Maritime Foundation, 30 September 2021, https://maritimeindia.org/maritime-domain-awareness-in-india-shifting-paradigms/

[59] Indian Navy, “Home IFC-IOR,” www.indiannavy.nic.inhttps://www.indiannavy.nic.in/ifc-ior/index.html

[60] Indian Navy, “About IFC-IOR,” https://www.indiannavy.nic.in/ifc-ior/about.html

[61] NewsIADN, Twitter Post, 5th October 2023, https://twitter.com/NewsIADN/status/1709943242769490322/photo/2

[62] “Global Community Must Collectively Aspire for Peace in this Age of Democratic and Rules-based World Order: Raksha Mantri Shri Rajnath Singh at Exercise MILAN in Visakhapatnam”, Press Information Bureau, 21 February 2024, https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=2007789

[63] NISHAR Brochure, Indian Navy.

[64] Discussion with an EEAS high representative, European Union Visitors Programme, Brussels, November 2023.

[65] “CRIMARIO – Critical Maritime Routes Indo-Pacific,” European Commission, https://fpi.ec.europa.eu/projects/crimario-critical-maritime-routes-indo-pacific_en#:~:text=In%202014%2C%20the%20European%20Union’s,the%20Western%20Indian%20Ocean%20region.

[66] “Maritime Security: Towards a CRIMARIO II extended to Southeast Asia,” Expertise France Groupe AFD, 03 February 2020, https://www.expertisefrance.fr/en/actualite?id=785808

[67] Niklas Nováky, “The Coordinated Maritime Presences Concept and the EU’s Naval Ambitions in the Indo-Pacific”, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/17816858221089871

[68] Dr Christian Kaunert & Dr Kamil Zwolski, “Somalia versus Captain ‘Hook’: Assessing the EU’s Security Actorness in Countering Piracy off the Horn of Africa”, Cambridge Review of International Affairs (2014), 27:3, 593-612, DOI: 10.1080/09557571.2012.678295, Pg 602.

[69] “Transformation of the Indian Navy to be a Key Maritime Force in the Indo-Pacific”, United Services Institute. August 27, 2021, YouTube Video, 0:21:26, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EXmo7m1gXE4&t=1292s

[70] “Responding First as a Leading Power”, Ministry of External Affairs, accessed on 20 March 2024, https://www.mea.gov.in/Portal/IndiaArticleAll/636548965437648101_Responding_First_Leading_Pow.pdf

[71] G Padmaja, “Revisiting ‘SAGAR’ – India’s Template for Cooperation in the Indian Ocean Region”, published on 25 April 2018, https://maritimeindia.org/revisiting-sagar-indias-template-for-cooperation-in-the-indian-ocean-region/

[72] “Factsheet – EU Maritime Security Strategy”, Directorate-General for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries, 10 March 2023, https://oceans-and-fisheries.ec.europa.eu/publications/factsheet-eu-maritime-security-strategy_en

[73] Moksh Suri, “Explaining EU Maritime Security Cooperation Through the Coordinated Maritime Presences Tool”, Finabel – The European Army Interoperability Centre, published January 2023

[74] “India Deploys Unprecedented Naval Might”, Reuters, 01 February 2024, https://www.voanews.com/a/india-deploys-unprecedented-naval-might-near-red-sea/7466220.html

[75] “EUNAVFOR Operation ASPIDES”, EEAS, 19 February 2024, https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/eunavfor-operation-aspides_en

[76] “Op Sankalp: 3rd Year of Indian Navy’s Maritime Security Operations”, PIB Delhi, Ministry of Defence, 19 June 2022, https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1835382

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!