Keywords: PLA Navy, Aircraft Carriers, Fujian, Liaoning, Shandong, EMALS, Power Projection, Far Seas, Maritime Security, Indian Ocean, J-15, J-35, Liu Huaqing, Gerard Ford, CATOBAR, Doraleh, Djibouti

“The carrier has become an important strategic weapon for China’s maritime ambitions, the development of naval power, and its strategic goals for sea lane security and regional influence”[1]

Admiral Liu Huaqing

China’s third aircraft carrier, the Fujian, completed the most technically demanding eighth phase of its trials in June 2025. The trial schedule reportedly included catapult-launch and recovery validation, as also the testing and integrations of the associated aircraft operating hardware and deck-based handling mechanisms.[2] As the first fully indigenously designed and built aircraft carrier, the Fujian signifies the material realisation of the long-held vision of Admiral Liu Huaqing — often dubbed the father of the modern PLA Navy — that had been articulated by him in the 1980s itself.[3] This particular Chinese carrier symbolises a conceptual shift from coastal defence to far-seas control, from brown-water bastion to blue-water assertion.[4] The Fujian, first seen in the public domain in June 2022, is China’s most technologically advanced carrier to date; and its development signals a decisive departure from earlier aircraft carriers, both in capacity and capability.[5]

The extended duration of Fujian’s testing programme and sea trials— now approaching two years— reflects both the scale of its technological advancement and the institutional learning curve, sought to be projected through the Chinese warship-building enterprise. The completion of its eighth, and reportedly most rigorous, sea trial marks a seemingly critical milestone in its due progression towards a modern aircraft carrier. This trial was markedly different, not merely in its intensity, but in the multi-layered facets of the complex systems under evaluation. While China Central Television (CCTV) did not confirm aircraft launches, it noted that the ongoing tests involved fifth-generation stealth fighters, specifically the J-35s. Satellite imagery and top-deck photographs were suggestive of limited ‘touch-and-go’ evolution by carrier-based aircraft, as seen by tyre marks on the flight deck.[6] Though circumstantial, these visual clues suggest that the PLA Navy is carefully advancing towards integrating its next-generation aircraft with the Electromagnetic Aircraft Launch System (EMALS) in a phased progression.

Trial Schedule of the Fujian Aircraft Carrier

China’s first aircraft carrier, the Liaoning, underwent ten sea trials before its commissioning in September 2012, while the second carrier, the Shandong, required nine (commissioned in December of 2019).[7] The Fujian incorporates an altogether different design and is reportedly equipped with higher technology equipment. Table 1 below outlines the sea trials conducted so far by the Fujian, highlighting key focus areas and critical takeaways.

|

Sea Trial |

Date Range | Focus Areas |

Remarks |

| First | 01–08 May 2024 | – Tested propulsion and electric

power systems. |

-Initial trials focused on fundamental alignment of individual sub-systems. |

| Second | 23 May–11 June 2024 | – Evaluated communication and reconnaissance systems – Further propulsion assessments. |

– Early-stage trials of electronic systems as a precursor to the next step of testing and tuning. |

| Third | 03–28 July 2024 | – Conducted navigation and manoeuvrability tests under various sea conditions. | – Provided data for maintaining operational efficiency in a complex maritime environment. |

| Fourth | 03–21 September 2024 | – Prepared for aircraft operations integration. – Potential testing of the catapultSystems. |

– First ever test of electromagnetic catapults identified the technical challenges required to be overcome for its reliable operation. |

| Fifth | 18 November-03 December 2024 | – Initiated carrier-borne aircraft operations. – Tyre marks observed on theflight deck, indicating aircraft‘touch and go’ trials. |

– Effective operation of carrier-based aircraft requires extensive all-around departmental coordination and training.

|

| Sixth | Late December 2024–Early-January 2025 | – Tested aircraft handling and

deck operations. |

– Real time aircraft handling at flight deck and in hangars was carried out.

– Space, time and procedural uniformity requirements to improve efficiency in high-tempo aircraft operations were ascertained. |

| Seventh | 18–27 March 2025 | – Shock trials to assess structural integrity under simulated combat conditions were conducted.

– Initial tests of air-defence and anti-submarines warfare systems were conducted. |

– Structural Resilience against combat-related stress is critical. – Large ships are more susceptible to attack from advanced anti-ship missiles; therefore, effective air defense systems are essential. – Potential vulnerabilities to submarine attacks highlight the need for robust anti-submarine warfare capabilities. |

| Eighth | 12–21 June 2025 | – Live testing of EMALS with fighter aircraft. – Simulated full-deck flightoperations under combat conditions. |

– Repeated launches to assess the deck wear patterns and long-term operational durability of launch and recovery equipment. – High-tempo flight operations can reveal limitations in sortie generation rate and deck logistics efficiency. |

Table 1: Fujian aircraft carrier sea trials, dates and explanatory comments

Source: Compiled by the Authors, from various China media reports

For a nation seeking to indigenously develop a next-generation aircraft carrier, these trials are being utilised to gain far greater insights than meeting routine procedural benchmarks. They endeavour to reflect stringent evaluation of industrial robustness, technological complexity, and the strategic breadth of systems’ autonomy. Each successive trial reportedly offered critical inputs into the aircraft carrier’s evolving proficiency towards its eventual operational readiness. However, there is no denying the fact that the PLA Navy still has to address many multifaceted challenges associated with making such a technologically advanced naval platform—that too the first of its type—fully operational.

Major Characteristics of the Fujian: Weapons Package and Air Wing

At the operational core of Fujian lies its EMALS, a next-generation technology that replaces traditional steam catapults. The presence of three electromagnetic catapults provides the wherewithal for the launch of heavier, longer-range, and more combat-capable aircraft, with the generation of higher sortie rates.[8] This offers a critical operational advantage by enabling the integration of a more diverse air wing, including early air warning (AEW) aircraft, electronic warfare (EW) platforms, and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), as well. This capability of launching aircraft of various sizes and weights would certainly provide more flexibility during carrier borne air operations, thus enabling enhanced strike coordination, role diversification and better airspace dominance.

Although the Chinese EMALS system is far from proven; the PLA Navy is quite close to joining the exclusive ranks of naval powers capable of deploying Catapult Assisted Take-off, but Arrested Recovery (CATOBAR)-configured aircraft carriers — previously limited to just the US and France. Table-2 below outlines the main technical specifications and capabilities of the Fujian, as currently gleaned from various open-source Chinese and other global media disclosures.

|

Category |

Specifications & Details |

Assessment & Significance |

| Displacement | 80,000 tons (full load, estimated) | Close to US supercarrier class in scale; marks a substantial leap from Liaoning (60,000 tons) and Shandong (70,000 tons). |

| Launch & Recovery

System |

3 x Catapults 4 x Arresting wires CATOBAR configuration |

First non-US carrier with EMALS; could offer more sortie generation rate, reduced airframe stress, and compatibility with heavier aircraft compared to STOBAR systems. |

| Aircraft Elevators | 2 deck-edge elevators | Essential for rapid movement of aircraft between the hangar and flight deck; design could impact tempo of sustained flight operations |

| Rotary-Wing Facilities | 5 marked landing spots for helicopters | Supports ASW, AEW, SAR, and logistic roles; it complements fixed-wing operations. |

| Air Wing (Projected) | 50–60 aircraft total Fixed-wing: J-15, potential J-35 (5th-gen), KJ-600 AEW Helicopters: Z-8/Z-20 for Utility & ASW roles |

KJ-600 AEW improves fleet-level situational awareness. The air wing composition mirrors US carrier doctrine. |

| Combat Roles Enabled | SEAD (Suppression of Enemy Air Defences) AEW&C coverage |

Defensive area denial to offensive power projection in far seas |

| Defensive Systems | HQ-10 short-range SAMs Rotary CIWS (Type 1130) Possible point-defense missile systems (e.g., RIM-116 SEARAM) Speculative: directed-energy or acoustic systems |

A combination of kinetic and possibly experimental systems suggests that the PLAN is preparing the Fujian Carrier for future multi-domain threats. |

Table 2: Technical Details of the Fujian Aircraft Carrier

Source: Compiled by the Authors from various sources

Lessons from the First and Second Aircraft Carriers

In the past, neither the Liaoning nor the Shandong were mere hardware experiments at carrier building; they served as institutionalised foundational blocks. These two aircraft carriers provided vital conceptual, technological and operational lessons to the PLA Navy before it could potentially induct carriers into its force-matrix and conduct viable operations in open waters. Over the past two years, both the Liaoning and the Shandong have ventured farther from home, pushing past the First Island Chain — that crucial geostrategic line from Japan to the Philippines — and increasingly operating in the Western Pacific, often in proximate waters of the US forward base of Guam.[9] Till May of 2024, the PLA Navy carrier-based aviators used to operate within 700 nautical miles (NM) of China’s coast. By December 2024, however, they were operating 1,300 NM out — well beyond the comfort factor of land-based diversionary airfield limits.[10] This achievement was, in fact, a precursor to the Chinese carrier-based aviation truly operating with confidence in the far-seas.

Yet the trend line tells a more nuanced story. The Liaoning took almost nine years to generate its first carrier-based sorties outside the First Island Chain.[11] The Shandong reduced this time frame to just two years; and the tempo has only picked up since then. In May of 2022, the Liaoning operated about 300 aircraft and helicopter sorties.[12] By April 2024, the Shandong exceeded 600 sorties in a single exercise.[13] These statistics clearly indicate that China is shifting gears in terms of operational efficiency — from an experimental mode to a far more combat-worthy, assertive one.

If the Liaoning was the proverbial classroom, and Shandong the quintessential lab, the Fujian is akin to a deliberately scripted thesis project — a unique platform to test high-intensity operations with a ‘never-before’ launch system, at scale and speed. The PLA Navy is just not aiming to launch more aircraft, it is trying to accomplish the integration of a complex air-sea battle group towards effective power projection — something the US has been a master of since the Cold War. In fact, the learning is not limited to the sea alone. Satellite imagery and model mock-ups indicate that the PLA Navy is modifying its carrier’s island configurations and sensor arrays to conform to the Fujian’s future command structure.[14] These visible trends force one to infer that this carrier does not just represent naval shipbuilding, but rather goes much beyond to doctrine-building ‘through metal and steel.’

The Fujian as a Force Multiplier

The commissioning of the Fujian will provide a three-carrier force to the PLA Navy, thus allowing the deployment of at least one carrier continuously in a given location or area of interest. Meanwhile, the other carriers can undergo maintenance and/or operational readiness training, reflecting the US Navy carriers’ rotational strategy.[15] Additionally, the Fujian’s operational architecture provides the essential foundation for future carrier doctrines centred on mobility, long-range ISR (Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance), layered defence, and offensive air dominance. In fact, the long-term goal is quite clear, in that the PLA Navy aims to transition from sea denial to sustained presence and shaping of maritime security environment, not only within the First Island Chain, but potentially extending into the Second Island Chain and even till the Indian Ocean.

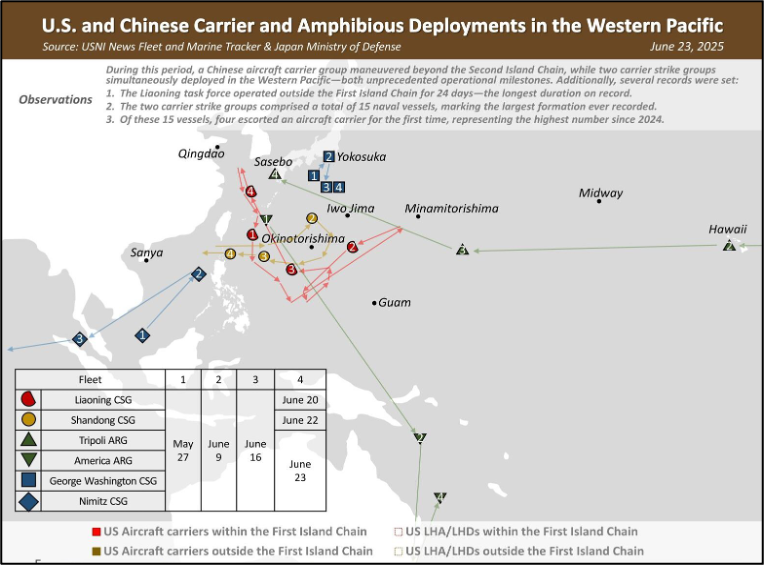

Yet another tactic by which China can achieve this objective is by simultaneous deployment of two carrier-based formations in the chosen area of interest. The propensity of the PLA Navy to deploy twin-carrier groups has been observed for last couple of years, with the Liaoning and the Shandong carrier groups often sailing together for short durations, while on their sea passages from north to south, or vice-versa. The two carrier-groups were recently observed to be deployed together in the general area between the First- and Second Island Chains in May-June 2025, in a sort of ‘strategic communication’ endeavour in response to the deployment of two US navy carrier-groups in the Western Pacific Ocean — the Nimitz group in the South China Sea and the George Washington group deployed south of main Japanese islands.[16] Figure 1 illustrates the deployment pattern of the Chinese aircraft carriers the Liaoning and the Shandong.

Figure 1: PLA Navy’s Twin-aircraft carrier deployment in the Western Pacific (May-June 2025)

Source: K. Tristan Tang, LinkedIn

It may be inferred from Figure 1 that both the Chinese carriers were observed to be operating within the First Island Chain in late May 2025. However, by June 2025, both carriers were conducting exercises in the sea area between the First and Second Island Chains, extending towards Guam. While this is not the first instance of both carriers conducting synergistic operations in a given extended area, their deployment pattern vis-à-vis US navy’s twin-carrier presence in the same extended area is a clear indicator of Chinese aspirations to match the US navy, force-for-force.

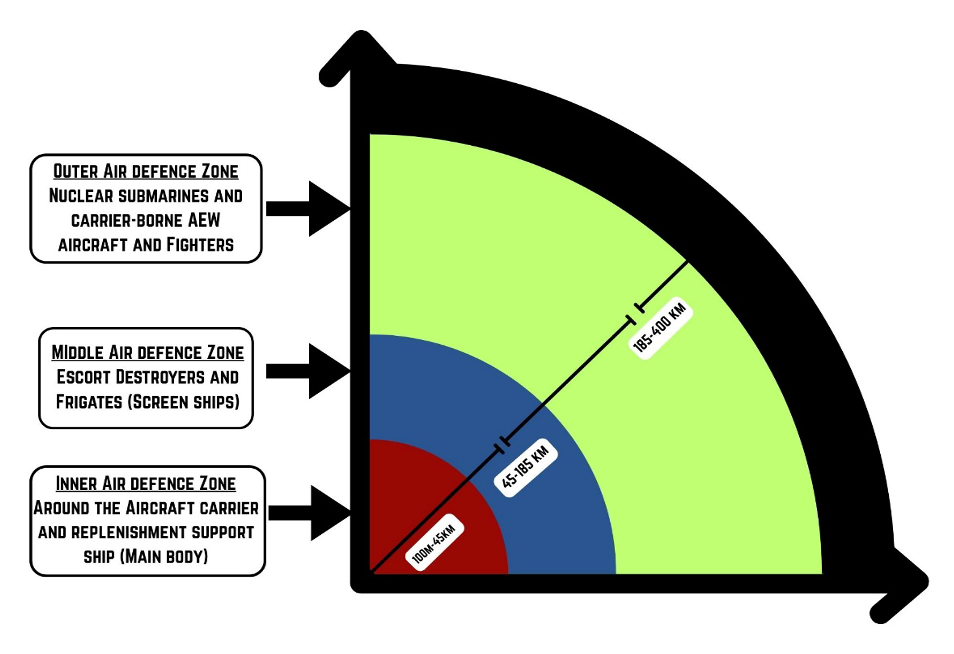

The PLA Navy is already in the process of finalising its concept of operations (CONOPS) for more a effective combat role for its aircraft carrier formations. The concept envisages the combat umbrella coverage of this twin aircraft carrier formation extending up to 400 km all around the strike force. One Western analysis of a CCTV-7 video on the composition and operational theory of the Chinese aircraft carrier groups, posted in the open domain, provides the details of various layered defence zones around such formations. It delineates the following three concentric defence zones, each associated with specific maritime tactics and sensor-shielding capabilities[17]:

- An Inner Defence Zone – 100 m to 45 km

- A Middle Defence Zone – 45 km to 185 km

- An Outer Defence Zone – 185 km to 400 km

These defence zones are represented in Figure 2 below for better appreciation.

Figure 2: A segmented representation of the Chinese Aircraft Carrier Battle Group Air Defence Zones

Source: Graphic prepared by the authors; Inputs from CMSI Note #6 of 2024

The Inner Defence Zone emphasises terminal defence utilising surface combatant systems and the aircraft carrier’s own close-range defences. The Middle Defence Zone involves large surface combatants equipped with advanced radars and guided missile systems for area defence, while the Outer Defence Zone is characterised by the deployment of submarines and carrier-based fixed-wing aircraft tasked with surveillance, long-range strike, and offensive operations.

The report also distinguishes between two primary flight operation patterns — split wave operations and continuous ones — with an aim to optimise operational coverage, tactical flexibility and combat readiness. These revelations clearly highlight the PLA Navy’s emphasis on adopting layered defence and versatile operational patterns to bolster the survivability and efficacy of its carrier strike groups (CSGs).

However, this technological leap-forward also introduces significant complexity. Chinese military analysts and naval planners have acknowledged that operating a CATOBAR carrier with such a sophisticated air wing demands an entirely new set of competencies — spanning deck-management, elaborate execution sortie generation — much like a perfectly choreographed symphony, logistical sustainment, and real-time strike planning.[18] Unlike the PLA Navy’s earlier Liaoning and Shandong aircraft carriers, which employed the simpler ski-jump launch systems and fielded limited fighter contingents, Fujian embodies a generational evolution in carrier aviation. The PLA Navy’s challenge now lies in training carrier-qualified pilots, (both for day and night missions) engineering skilled deck crews, and integrating these capabilities into coherent naval doctrines—none of which can be achieved solely through hardware advances.[19]

India’s View on China’s Fujian Aircraft Carrier Programme

Indian strategists and China watchers have been observing China’s third aircraft carrier, the Fujian, with heightened interest. While the Chinese media claims that this is a technological breakthrough comparable to US supercarriers, Indian analysts are more circumspect in their assessment, noting that the ship is not yet commissioned and operational, and that the PLA Navy will still take a long time before it can reach the operational standards befitting a formidable aircraft carrier well-integrated with the PLA Navy’s CONOPS. While the Fujian is equipped with advanced systems, it will still face numerous challenges in integrating new systems into actual maritime combat conditions. Indian analysts also posit that China often rapidly develops technologically-advanced assets without sufficient training or proven plans; a widespread affliction which also implies that the Fujian might fall well short of the standards expected of a reliable combat warship.[20]

From a defence industrial perspective, Indian naval thinkers underscore the lack of transparency and reliability in China’s shipbuilding claims.[21] The Fujian is often touted as indigenously designed and constructed, yet there is limited credible verification of the degree of genuine indigenous innovation, especially in the areas of EMALS, integrated power systems, and advanced aircraft operational mechanisms. Some Indian assessments also question whether the PLA Navy has the necessary experience in executing blue-water carrier operations, particularly in complex multi-domain scenarios. As India’s experience with the Vikramaditya and the Vikrant has shown, aircraft carrier efficacy lies not only in hull construction, but in the efficient integration of air wing, battle group coordination, and logistical endurance[22] — all areas where the PLA Navy is still learning, catching up, and preparing the requisite logistical supply and support chains.

In operational terms, India has noted that while China may possess three aircraft carriers on paper, their true combat integration within the specific task forces remains untested and unproven. The probable employment of the Fujian is interpreted less as a response to immediate security needs, and more as a long-term signalling effort aimed at regional power projection, especially in the Western Pacific.[23] Indian perspectives also tend to frame Fujian not as a threat in itself, but as a catalyst for engendering instability in maritime Asia, especially when seen in conjunction with China’s expanding Strategic Strong Points (SSPs) in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) — from Djibouti in the west potentially to the Myanmar coastline in the east. Moreover, the PLA Navy’s doctrinal ambiguity regarding carrier exploitation — as defensive bastion or offensive tool — raises due concerns for Indian analysts.

Indian naval circles also draw attention to China’s overreliance on numerical superiority without corresponding combat experience in a blue-water domain. As some analysts have pointed out, even the most sophisticated carriers are only as effective as the supporting ecosystems — the carrier-capable aircraft, trained pilots in large number, and an integrated logistics and maintenance framework. The Fujian’s EMALS, for instance, may actually require a long time before it gets certified for operational exploitation. In this regard, the experience of the US Navy’s Gerard Ford aircraft carrier presents a sobering analogy, with its EMALS system finally achieving operational clearance after a prolonged trial, a good four years after its commissioning.[24] There is also a perception that the PLA Navy’s fast-paced carrier push is driven more by political considerations — particularly with an aspiration to close the gap with the US Navy and overshadow regional peers—than being driven by any coherent maritime doctrine. Indian analysts, therefore, naturally view this conundrum as a point of vulnerability rather than one of strength.

Future Trajectory of China’s Aircraft Carrier Programme

The PLA Navy’s aircraft carrier programme, marked by rapid expansion and increasingly sophisticated platforms, has emerged as a symbol of China’s transformation into a credible maritime power. From the retrofit-heavy Liaoning to the indigenously constructed Shandong, and now the technologically ambitious Fujian — all within a span of two decades — China’s progression reflects a concerted effort to transition from a historically coastal navy to a full-spectrum, blue-water force. China has cryptically announced that it is constructing a fourth aircraft carrier (Type 004) in its Dalian shipbuilding facility.[25] While this is likely to be a follow-on of the Fujian carrier, there is no clarity with regard to its EMALS and its propulsion system.

At the heart of China’s carrier push is the desire to match — if not eventually rival — US CSG capability.[26] The Fujian essentially embodies this aspiration. However, Chinese carriers, unlike their US counterparts, still lack actual at-sea combat integration, such as the experience required to reach operational maturity and sustained logistics management, among other details. Therefore, despite its visual resemblance to US Ford-class carrier, the Fujian will probably continue to be well short of the combat capabilities that a US aircraft carrier can bring to bear. The Chinese carrier can hope to operationally match-up only well-after the innovative EMALS system had been proven to be combat worthy. In the present state, the PLA Navy’s carrier programme, at best, can be said to serve China’s ‘regional seas dominance’ objective, enabling it to influence the regional geopolitics only in the Western Pacific littoral.

Conclusion

China’s aircraft carrier programme is undoubtedly a powerful symbol of its maritime ambitions, and future progression — especially the unconfirmed speculations about the fifth and sixth carriers — will likely focus on sustained presence, nuclear propulsion, carrier-based UAV integration, and twin-carrier synergistic employment. However, a rational and unbiased outlook must consider that the road to genuine “far seas dominance” is neither short, nor easy and straightforward. While China has proven it can build large platforms at scale, its ability to employ them in a sustained, strategic maritime presence roles — especially in the Indian Ocean — still remains debatable. Moreover, the PLA Navy’s aircraft carriers have thus far remained somewhat tethered to home waters, or have ventured only into the Western Pacific under controlled peace time conditions.

These challenges and limitations notwithstanding, future developments in the Chinese aircraft carrier programme — such as a fourth carrier (possibly nuclear-powered) — and a progressively improving naval logistic network in the IOR, suggest that China is laying the groundwork for sustained carrier presence in the region. The construction of an approximately 330-metre long jetty at the Chinese naval facility in Doraleh multipurpose port of Djibouti in January 2020, which is capable of berthing an aircraft carrier alongside, offers some credence to this argument.[27]

This has significant implications for all States in the IOR littoral, including India. The possibility of a dual-carrier PLA Navy presence in the Indian Ocean would necessitate a substantial rethink within the Indian maritime security establishment about own fleet missions, exercises and operational plans, long-range ISR (Intelligence, Surveillance, Reconnaissance) employment, sub-surface CONOPS, and readiness levels, among many other maritime security realms.

The IOR for now, remains a psychological frontier more than an operational one for China. For India and the broader Indian Ocean littoral, the strategic task lies in not matching China carrier-for-carrier — or platform to platform — but in developing asymmetric capabilities and countermeasures, bolstering multilateral maritime partnerships, and ensuring a credible, resilient, and transparent regional naval posture. The future of naval power in Asia therefore must not only be decided by steel and steam, but by synergistic collaboration, mutual trust-building, and a ‘new era’ of operational maturity, after due assessment of the threat-pattern that may emerge in near- to mid-term timeframes.

******

About the Authors

Captain Kamlesh K Agnihotri, IN (Retd) is a Senior Fellow at the National Maritime Foundation (NMF), New Delhi. His research concentrates upon maritime facets of hard security vis-à-vis China, Pakistan, Russia, and Turkey. He also delves into maritime security challenges in the Indo-Pacific Region and their associated geopolitical dynamics. Views expressed in this article are personal. He can be reached at kkumaragni@gmail.com

Mr Chemi Rigzin is a Research Associate at the National Maritime Foundation. He holds an MPhil degree in Geography from Delhi University. His research currently focuses upon critical areas of hard security such as PLA naval modernisation, and Chinese port construction and facilities. He also delves into more generalised threats to shipping and maritime connectivity within the Indo-Pacific. He may be contacted at pcrt4.nmf@gmail.com

Endnotes:

[1] Admiral Liu Huaqing was the commander of PLA navy from 1982-87. The Admiral also served as the vice chairman of Central Military Commission (CMC) from 1992-97. This quotation ascribed to Admiral Liu Huaqing has been taken from the article by Andrew S. Erickson and Andrew R. Wilson, ‘China’s Aircraft Carrier Dilemma’, Naval War College Review: Vol. 59: No. 4, (Autumn 2006’), pp. 13-45. The authors in turn, have cited the ‘Memoirs of Liu Huaqing’ (People’s Liberation Army Press, Beijing, 2004). The original work was in Chinese language and the authors claim to have checked the correctness of the quote against the translations provided by the US Government translators, the Foreign Broadcast Information Service (FBIS).

[2] Liu Zhen, “China’s advanced Fujian carrier conducts ‘intensive’ eighth sea trial”, South China Morning Post, 25 May 2025, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/military/article/3311729/chinas-advanced-fujian-carrier-conducts-intensive-eighth-sea-trial?utm

[3] Andrew S. Erickson and Andrew R. Wilson, “China’s Aircraft Carrier Dilemma”, Naval War College Review: Vol. 59: No. 4,

[4] Ibid

[5] Chris Panella, “China built a new modern aircraft carrier, but it’s got a ‘steep learning curve’ to beat before it can match the US Navy”, Business Insider, 8 June 2024, https://www.businessinsider.com/chinas-new-aircraft-carrier-more-to-learn-to-match-us-2024-5?utm

[6] Liu Zhen, “China’s advanced Fujian carrier conducts ‘intensive’ eighth sea trial”, ibid.

[7] Zhao Lei, “China’s third aircraft carrier begins its maiden sea trial”, China Daily, 01 May 2024, https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202405/01/WS663186e2a31082fc043c4f91.html?utm

[8] Liu Xuanzun and Guo Yuandan, “China’s first electromagnetic catapults-equipped aircraft carrier holds intensive sea trials: official media”, Global Times, 25 May 2025, https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202505/1334807.shtml

[9] Maritime Executive, “For the First Time, Two Chinese Carriers Deploy in the Western Pacific”, 10 June 2025, https://maritime-executive.com/article/for-the-first-time-two-chinese-carriers-deploy-in-the-western-pacific?utm

[10] Benjamin Sando, “Why did the PRC restrict 1000 Kilometres of Airspace in the Pacific?”, Global Taiwan Institute, 05 February 2025, https://globaltaiwan.org/2025/02/why-did-the-prc-restrict-1000-kilometers-of-airspace-in-the-pacific/?utm

[11] China Military, “Tenth anniversary of J15’s first sortie on aircraft carrier Liaoning”, Ministry of National Defense of the People’s Republic of China, 24 November 2022, https://eng.mod.gov.cn/xb/News_213114/Videos/4927253.html?utm

[12] Liu Xuanzun and Guo Yuandan, “China’s Liaoning carrier group ends Pacific navy drills aimed at Taiwan independence forces”, SCMP, 24 May 2022, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/military/article/3179001/chinas-liaoning-carrier-group-ends-pacific-navy-drills-seen

[13] Jack Lau, “China’s Shandong aircraft carrier sets new sortie benchmark in military exercises”, SCMP, 28 April 2023, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/military/article/3218622/chinas-shandong-aircraft-carrier-sets-new-sortie-benchmark-military-exercises?utm

[14] Rear Admiral Monty Khanna (Retd), “China is well on the path towards a Nuclear-Powered Aircraft Carrier”, National Maritime Foundation Website, 15 January 2025, https://theasialive.com/pla-navy-poised-to-challenge-global-waters-chinas-new-aircraft-carrier-spotted-in-latest-satellite-imagery/2024/10/30/?utm

[15] Mike Sweeney, “Challenges to Chinese Blue-Water Operations”, Defense Priorities, 30 April 2024, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/challenges-to-chinese-blue-water-operations/?utm

[16] K. Tristan Tang, LinkedIn Post, 01 July 2025, https://www.linkedin.com/in/k-tristan-tang/recent-activity/all/

[17] Daniel Clayton Rice, “CMSI Note #6: Sharpening the Sword: Chinese Navy Aircraft Carrier Battle Group Defense Zones” (2024). CMSI Note #6, 16 July 2024. https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/cmsi-notes/6/

[18] Liu Xuanzun and Guo Yuandan, “China’s first electromagnetic catapults-equipped aircraft carrier holds intensive sea trials: official media”, ibid.

[19] Andrew S. Erickson, “Chinese Shipbuilding And Seapower: Full Steam Ahead, Destination Uncharted”, CIMSEC, 14 January 2019, https://cimsec.org/chinese-shipbuilding-and-seapower-full-steam-ahead-destination-uncharted/

[20] Bobby Yadav, “China’s Rising Naval Power: Beyond Numbers Lies the True Test”, Defence XP, 3 May 2024, https://www.defencexp.com/chinese-navy-rising-power-beyond-numbers-lies-the-true-test/?utm

[21] Monty Khanna, “Understanding China’s naval ship building industry – lessons India can learn”, Maritime Affairs: Journal of the National Maritime Foundation of India, 15(1), 1–14, https://doi.org/10.1080/09733159.2019.1631512

[22] Government of India, Press Information Bureau, “Combined Operations Of INS Vikramaditya And INS Vikrant” Ministry of Defence, 10 June 2023, https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1931254

[23] The Maritime Executive, “For the First Time, Two Chinese Carriers Deploy in the Western Pacific”, 10 June 2025, https://maritime-executive.com/article/for-the-first-time-two-chinese-carriers-deploy-in-the-western-pacific?utm

[24] While Gerald Ford carrier was commissioned on 22 July 2017, its EMALS launch system was declared safe to launch aircraft for operations only in December 2021. See Ronald O’Rourke, “Navy Ford (CVN-78) Class Aircraft Carrier Program: Background and Issues for Congress”, US Congress website, 21 March 2025, https://news.usni.org/2024/12/19/report-to-congress-on-gerald-r-ford-aircraft-carrier-program-4

[25] Liu Xuanzun, Guo Yuandan and Li Yawei, “Defense Ministry responds to US report ‘China building large nuclear-powered aircraft carrier’, says it’s ‘purely speculative’”, The Global Times, 14 March 2025, https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202503/1330128.shtml

[26] Captain Kamlesh K Agnihotri, IN (Retd), “The Vikrant Aircraft Carrier Reborn: Indian Navy’s ‘Atmanirbharata’ Endeavour Comes Of Age”, NMF Website, 02 September 2022, https://maritimeindia.org/the-vikrant-aircraft-carrier-reborn-indian-navys-atmanirbharata-endeavour-comes-of-age/

[27] Brian Gicheru Kinyua, “New Pier at China’s Djibouti Base Could Accommodate Carriers”, Maritime Executive, 30 April 2021, https://maritime-executive.com/article/new-pier-at-china-s-djibouti-base-could-accommodate-carriers

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!