Abstract

The threat landscape in the maritime domain extends beyond the confines of the sea, often spilling over from land. The land-based groups, falling under the category of Violent Non-State Actors (VNSAs), have been increasingly acquiring maritime capabilities, to exploit the vast swath of seas at their disposal for propagating violence. This land-Sea nexus of maritime crime becomes more evident, when these groups start to derive economic benefits through illicit activities. Therefore, to comprehensively grasp maritime crime at sea, it is imperative to track hostility on land, overcoming the paucity of data in structural and institutional responses to maritime security. In the realm of maritime security, data plays a pivotal role, serving as a cornerstone for informed decision-making, threat detection, and the coordination of responses within the dynamic and intricate maritime environment. However, a crucial question emerges: are we analysing the right data to achieve this overarching goal? A meticulous analysis of data fields not only provides essential insights but also forms the basis for crafting a comprehensive tapestry of holistic maritime security.

Keywords

Maritime Risk Profile (MRP); Western Indian Ocean; Violent Non-State Actors; Data Constraints

***

In the 21st century, the fabric of maritime insecurity seems to be woven with the threads of unconventional, intricate, and overlapping sets of threats. The maritime threat spectrum encompasses traditional and non-traditional challenges, including calamities resulting from both natural and manmade factors. A combination of these threats, such as climate change and challenges in areas beyond national jurisdiction (ABNJ), further complicates the maritime security scenario.[1] A host of maritime crimes falling under the category of non-traditional threats, including maritime terrorism, piracy, and arms robbery, and illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing, to name a few, stem from factors originating on land. To effectively study insecurity at sea, it is imperative to study land-oriented drivers, such as unstable States, onshore political violence, weak coastal management, a lack of rule of law, and weak maritime enforcement capacity.[2]

It is true that at sea, threats come from all directions. The land-based facets of maritime insecurity are a crucial pre-requisite in understanding the holistic maritime security picture. Scholars delving into the study of land-sea nexus of maritime transnational organised crime emphasise the need to explore intermediary agents involved in sustaining the link between land-centric drivers and actions of violent non-State actors (VNSAs) and their sea operations. These ‘intermediate agents’ include factors such as societal incoherence, socio-economic breakdowns, and the presence of ungoverned spaces (parts of territory where formal governments have little or no influence). For example, Somali piracy, in principle is understood as a “desperate act of (in)security by nomadic non-State actors,”[3] whose fishing grounds were damaged by hazardous waste and whose food and economic security have been threatened due to unlawful fishing. Such ruptures within the socio-economic fabric are a feature of a fragile State. As per the International Monetary Fund (IMF), fragile States exhibit qualities that significantly hinder their economic and social outcome — which includes ineffective governance, lack of administrative capability, ongoing humanitarian crises, enduring social tensions, and frequent instances of violence in the aftermath of armed conflict and civil war.[4]

Some of the world’s most volatile and fragile states are situated along coastlines, and due to their proximity to the sea, rebel factions, transnational criminal networks, and terrorist organisations exploit maritime spaces to pursue their interests. State fragility leads to a lack of governance, ultimately resulting in poor law-enforcement mechanisms. Consequently, instability spills into the maritime domain. While oceans serve as conduits of prosperity and are central to the modern global economy, they also hold significance for VNSAs. As once demonstrated by Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) cadres, who at the peak of the Sri Lankan civil war had developed a sophisticated maritime network of assets, logistic channels, and operational tactics, coastal and island-based VNSAs have increasingly been turning to the sea to exploit the maritime domain for operations, manoeuvring, financing, and sustaining their campaigns of brutality.[5]

The focal maritime region for this article is the Western Indian Ocean, which comprises the littoral and island states of eastern and southern Africa. This region stretches from Somalia in the north to South Africa in the south, encompassing the southwestern Indian Ocean Island States. It is essential to examine this area comprehensively by assessing the regional States and the factors causing instability in them.

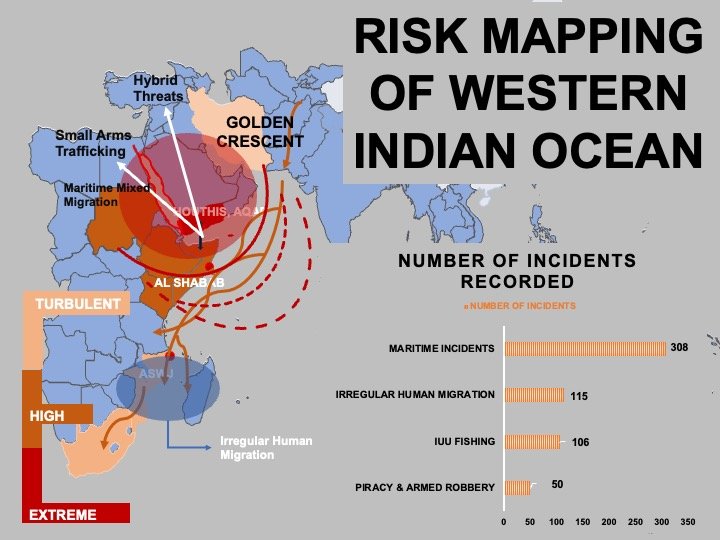

The Western Indian Ocean Region (WIOR), which spans the Arabian Sea, the Red Sea, and the Indian ocean, hosts at least 19 active VNSAs.[6] Three of these, namely, the Houthis in Yemen, Al Shabaab (Al Qaeda and ISIS factions) in Somalia, and Ahlu Sunna Wa Jamaa in Mozambique, particularly worrying to the safety, security, and stability of the eastern Africa littoral. Between November and March of 2023, a review of recent events reveals that the Houthis attacked more than 60 vessels in the Red Sea, causing direct hits from missiles and drones on 16 vessels.[7] On the other hand, Al-Shabaab in Somalia and Ahlu Sunna Wa Jamaa (ASWJ) in Mozambique, too have been increasingly exploiting the maritime space for tactical support, targeting and seizing assets and resources at sea, engaging in the trafficking of goods and trade, and resorting to taxation and extortion.[8]

Maritime security concerns gained significant traction and considerably sharpened focus following the attack on the USS Cole in October of 2000,[9] while the domain of the air was brought into even sharper relief in the terrorist attacks on the USA in September of 2001, popularly known as “9/11”. An important outcome of “9/11” was the reshaping of the entire world of surveillance into one in which all domains — land, sea, air, space, and cyber — were recognised as being relevant to both terrorism as well as State-based endeavours in terms of counterterrorism. The subsequent “global war on terror” (GWOT) necessitated a transition in surveillance focus, away from a concentration solely or even principally upon conventional military threats emanating from State ambitions, and towards far less structured terrorist international networks.[10]

If surveillance entails collecting actionable information to comprehend things better, then data is the means to form that information. As a result, data gathered for enhancing maritime security needs to be diversified by factoring not just security-incidents occurring at sea but also their onshore instigators and the motivations of the latter. This article seeks to address a prevalent data gap by proposing a methodological pre-step to maritime domain awareness (MDA) and maritime situational awareness (MSA), namely, the creation of a risk profile of volatile maritime entities — both State and non-State. In many such nations, it is onshore insecurity that translates into challenges within their respective maritime domains. The Western Indian Ocean is one such sub-region that requires analysis. Here, a complex web of maritime crimes results from or is exacerbated by violence brewing within State boundaries.

Incidences of organised violence that have occurred in the world between the years 1989 and 2022, have more than doubled. In the year 1989, there were some 86 incidences of major violence[11] — encompassing “one-sided”; “extra systemic”; “non-State”; “intrastate’, and “interstate” forms. By 2022, this number had risen to 182.[12] According to the conflict database and datasets created by the Uppsala Conflict Data Program, 54 of these 182 were State-based conflicts. More pertinent is the fact that nearly 25 of these involved coastal or island countries.[13] It is critical to study global conflict indices and indicators such as the Uppsala Conflict Dataset, the ACLED Project, the Global Terrorism Index, etc., as these serve as early warning and forecasting tools.

Developing a risk profile involves a qualitative analysis of the threats faced by a country and its maritime-oriented stakeholders. The process delves into a detailed examination of the factors that generate and then sustain specific threats. This often leads to the perpetuation of the vicious cycle of State-actor asymmetry. The approach requires a nuanced understanding of the reasons underpinning the emergence of threat. Furthermore, a thoroughly developed risk profile offers an opportunity to adopt a field-based approach, enabling the continual adjustment of research tracks until a desired end state is achieved – namely, the establishment of good order at sea. The primary objective of the Maritime Risk Profile (MRP) is, accordingly, to bring clarity to the nature of risks and their causal relationships within the impacted area, thereby providing a precise understanding of the risks at play.

At the stage of primary assessment, the MRP process requires the creation of a data “ecosystem” that encompasses a study of protracted conflicts that have either broken out or are simmering across the world, and which have pushed the status of the States from ‘stable’ to ‘fragile’ or ‘weak’, to ‘collapsed’ or ‘failed’ States.[14] Due to the fragmentation of institutional and administrative structures responsible for law and order or political deterioration, some of these States function as lawless units. In such a context, violence tends to follow the path of least resistance for survival, and the sea often becomes that ‘path’. Yet, direct access to the sea is not always a decisive factor in a volatile State being transformed into a source of violence. For example, illicit opium, opiates, and opioids from Afghanistan — clearly a landlocked State — are trafficked overland to points along the coast within and in the proximity of the Persian Gulf and farther west and enter eastern Africa through multiple gateways on the Swahili coast.[15] It is evident that lawlessness finds its way to the sea in multiple ways. Therefore, it is imperative to globally track conflicts on or more of whose outflow paths lead to the sea.

Developing a Maritime Risk Profile (MRP) for the Western Indian Ocean (WIO)

The dynamic nature of risks is evident in the Red Sea and its chokepoints (the Suez Canal and the Strait of Bab-el-Mandeb), as also in the Gulf of Aden (GoA), where the maritime risks have proliferated from just piracy to now encompass the spillover effects of traditional wars.[16] Table 1 lists countries of the WIO, including Yemen and those on the Horn of Africa, based on various evaluators utilised to generate country-wise rankings:Top of Form Bottom of Form

|

Country |

Evaluator |

|||

|

|

ACLED Conflict Index[17] | UPPSALA Conflict Data Programme[18] (Number of conflict-related deaths) | Global Terrorism Index Score[19] | Fund for Peace: “Fragile State Index”[20] |

| Yemen | Extreme | 65,616 | 4.951 | High Alert |

| Somalia | High | 57,846 | 7.814 | Very High Alert |

| Djibouti | – | 516 | 2.035 | High Warning |

| Eritrea | – | 19,940 | 0 | Alert |

| Ethiopia | High | 300,058 | 1.272 | High Alert |

| Kenya | High | 6,302 | 5.616 | High Warning |

| Tanzania | – | 149 | 2.267 | Elevated Warning |

| Mozambique | Turbulent | 10,822 | 6.627 | Alert |

| South Africa | Turbulent | 5,660 | Not Included | Elevated Warning |

| Madagascar | Turbulent | 234 | Not Included | High Warning |

| Mauritius | – | – | Not Included | Very Stable |

| Comoros | – | – | Not Included | High Warning |

Table 1: Collation of the Country-wise Score & Categories

Source: Author’s compilation from various sources

These indicators provide a comprehensive view of each country’s current situation in terms of conflicts, terrorism, and state fragility. As may be observed from Table 1, while low intensity disturbances are recorded in a number of States, three — Yemen, Somalia, and Mozambique — are currently high on every conflict indicator, thereby becoming the most volatile States in the WIO. The “Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project” (ACLED) clearly reveals Yemen as having been classified as “extremely volatile”. The Horn of Africa along with Kenya, falls into the “high-risk” category, while countries like South Africa, Mozambique, and Madagascar are characterised as “turbulent”.[21]

Since the inception of the Yemen crisis in 2014, this country has become a primary source of geopolitical risk, with several of these risks having cascading effects. The country’s complex conflict landscape has expanded manifold and at the present juncture, a majority of the violent activities are concentrated along the west coast (the Red Sea coast), along the western Yemen-Saudi border, and in areas covering south-central Yemen. Maritime attacks by the Houthis began in 2015-2016 when the HSV-2, the Swift, was targeted off the coast of Yemen by a missile.[22] In this phase, after securing control of the western Red Sea coast, the Houthis turned to shoreline shelling. Then, in 2017, the group expanded its tactics to include waterborne improvised explosive devices (WBIEDs). Following the collapse of the UN-brokered truce in 2022, the group escalated its activities, conducting long-range drone and missile attacks on vessels traversing the Red Sea.[23] Since 19 November 2023, in the aftermath of the Israeli-Hamas conflict, the Houthis have conducted more than 60 attacks on commercial and military ships in the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden, singling out those with connections to the State of Israel.[24]

The second source of maritime insecurity stems from Somalia, where an absence of credible political governance has given rise to virulent non-State actors such as the Al-Shabaab. Somalia, though often perceived as a homogenous state, is actually a deeply fractured entity, with two autonomous regions, namely, Somaliland — which declared independence in 1991 — and Puntland — which declared autonomous status in 1998. (Eyl and Bandar Bayla are some of the more well-known pirate dens in Puntland). Consequently, counter-piracy measures may be expected to encounter legal constraints due to jurisdictional issues. Criminal groups control large parts of central and southern Somalia, with a very substantial proportion of their income being derived from extortion and protection racketeering activities. Somalia is also a source of human trafficking, drugs and arms smuggling and fauna crime.[25] In addition to Houthi attacks, Somali piracy has re-emerged in the region, marking the onset of a fresh phase of pirate attacks in the Gulf of Aden (GoA). According to data from the EUNAVFOR-Op ATALANTA 2024-report entitled “Maritime Piracy Sitrep – GoA/Somali Basin,”, between end-November 2023 and end-January 2024, there have been four confirmed and fourteen attempted cases of piracy in the area.[26] Moreover, Al-Shabaab is not the only VNSA operating in Somalia; the Islamic State in Somalia Province (ISSP) is another faction that is active in Puntland.[27] This group’s early establishment of control over the strategic seaport of Qandala in 2016 provided it with access to significant resources, including weapons, supplies, and trainers, often through its affiliates in Yemen.[28]

There are numerous studies that have traced the causes of piracy and the rise of VNSAs in Somalia. One argues that when a country falls in a “poverty trap”, it looks for sustainable economic alternatives. [29] Before falling into anarchy, Somalis traditionally used to practice agriculture and pastoralism. However, as has been pointed out by the Somaliland NGO, “Candlelight for Health, Education & Environment”, “The civil war (1988–1990) and the subsequent civil strife (1994-1997) had a serious effect on both terrestrial and marine resources of Somaliland and an impoverishing effect — in fact to the point of destitution….”[30]

With a comparatively long coastline (3,333 km) Somalia has an abundance of marine resources. The annual maximum sustainable yield (MSY) of the fish stocks available in the waters off Somaliland alone is estimated to be between 90,000 and 120,000 metric tons a year, but less than 5 per cent of that quantity was being harvested by the Somalis themselves who seemed to prefer livestock meat. The popularity of fishing as a dietary source has long been constrained by a lack of infrastructure required to support a fisheries industry (such as cold storage, ice making machines, etc.), a general lack of awareness of the protein-benefits of fish consumption, and outdated artesian skills. On the one hand, these factors kept the country’s focus away from its otherwise fertile fishing waters. On the other, as civil strife gripped the land, the ability of Somalia to police its waters dwindled. The situation was greedily and callously exploited by distant-water fishing fleets from Europe, the Americas, and East Asia, all of whom took full advantage of the lack of governance in the country by extensively fishing in the Somali waters without any licences. Thus, “the fishing industry has deteriorated into a ‘free for all’ equally accessible to the world’s fishing fleets. Vessels from various countries have continuously fished in the Somali waters in an unreported and unregulated manner. This has had far reaching consequences… on the sustainable management of the marine environment… Reports on toxic waste dumping in the territorial waters of Somalia/land have been recurring over the past decade or so…”[31] All this has worsened the country’s food security and has driven it inexorably into a never-ending cycle of resource-conflict. The extensive IUU fishing has had cascading effects where either conflict at sea between foreign and domestic fishing communities was becoming increasingly frequent, eventually resulting in the nature of the society being altered altogether, with manifestations such as the proliferation of pirates and local admiration for them since they were visibly abele to generate prosperity for their families and their clans. Al Shabaab, at various stages of its operations is believed to have replicated these trends of piracy being not merely accepted but admired by the local populace along the coast. For instance, in 2012, a recognised pirate leader, Ciise Yulux, reportedly supplied funds and equipment to fighters associated with both Al-Shabaab and Al-Qaeda. Furthermore, through an arrangement in Xarardheere, a port town north of Mogadishu, pirates paid a ‘development tax’ of 20 per cent to Al-Shabaab to retain their boats in port.[32]

Insecurity at sea, as exemplified by maritime crime in the Gulf of Aden (GoA), has prompted the international community to opt for intensified securitisation of the region. During the peak of piracy from 2005 to 2012, local fishers in Yemen as well as those in Somalia felt beleaguered as a cascade of stringent security measures were enforced in the region effectively preventing them from deriving mutual gains from each other’s marine resources.[33] In the more recent context, the international strategic security community has engaged in extensive deliberations on the reasons behind the sudden surge in pirate attacks amidst the Houthi attacks. While this is presumed to be an ‘opportunistic gambit’ aimed at capitalising upon the shift of security focus to the southern Red Sea, this may well be a simplistic explanation, masking more structural causes. The latter are important, given that Eritrea and Sudan are two other zones of near perpetual conflict wherein the law-and-order vacuum is exacerbating the crisis in and off the Horn of Africa.

A third source of insecurity emerges from the activities of the Islamic State (Mozambique), an armed group identified as Ahlu Sunna Wa Jamaah (ASWJ) or Al Sunnah. Since 2017, this group has actively carried out coordinated attacks in Cabo Delgado, the northernmost province of Mozambique, transforming it into a perilous battleground marked by an enduring insurrection. Since the inception of its violent activities, ASWJ has exploited the sea due to the region’s weak maritime enforcement capacity and a lack of adherence to the rule of law. In October 2017, ASWJ initiated its violent campaign with an attack on a police station in Mocímboa da Praia. There is adequate evidence to state that at least since March of 2020, the group has consistently exhibited a high capability and intent to utilise maritime routes for operational purposes. ASWJ insurgents are known employ ships such as front-loading ferries for amphibious operations by means of which they facilitate the movement of fighters and supplies to target port-infrastructure. This is exemplified by the August 2020 attack in Mocímboa da Praia, where an HIS-32 Interceptor patrol vessel was reportedly sunk through the use of a Rocket-propelled Grenade (RPG).[34] In March of 2021, the coastal town of Palma fell victim to an ASWJ attack.

The presence of maritime-capable insurgents in Mozambique is of particular concern given that Mozambique abuts the Mozambique Channel, which is one of the four critical chokepoints in the Western Indian Ocean (WIO). Following the discovery of Africa’s largest natural gas deposits in and off northern Mozambique, the importance of the Mozambique Channel has surged, making it a lynchpin for the energy security of a number of including India, Japan, South Korea, and the People’s Republic of China (PRC). ‘Total Energies’, a leading French energy giant, had to cease its $20 billion-worth of exploration and production (E&P) activities at its Afungi site near Palma due to repeated attacks by insurgents.[35] The Mozambique LNG Project, part of the company’s portfolio, has been suspended under a force majeure clause, since April 2021 and, despite occasional announcements to the contrary, is yet to resume operations. Consequently, although the Mozambique Channel has emerged as a promising energy security zone, thanks to the massive potential in the ten natural-gas fields in Mozambique, this potential remains unrealised due to the persistent presence of ASWJ since 2017. Ensuring absolute security in the channel is imperative, especially given the expanding insecurity in the Red Sea and the consequential rerouting of global trade around the Cape of Good Hope.

Data Trends in the Maritime Security of WIOR

Information derived from land-centric patterns of maritime insecurity provides a valuable tool for creating a potential risk-map of a volatile maritime region having asymmetric actors. In its 2020 report entitled, “What We Know About Piracy”, published by the Safe Seas Programme and Stable Seas Network, the following crucial questions were raised[36]:

- Are we analysing the right piracy data?

- Who collects data on maritime piracy and armed robbery against ships?

- Which maritime stakeholders benefit from this data?

Quantifiable data regarding the number of piracy incidents at sea is systematically recorded by various information fusion and data collection centres. Numerous international and regional organisations, including the “International Maritime Bureau” (IMB) of the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) and the “Regional Cooperation Agreement on Combating Piracy and Armed Robbery against Ships in Asia-Information Sharing Centre” (ReCAAP-ISC), provide essential baseline data on maritime piracy. These organisations, in collaboration with entities such as the International Criminal Police Organisation (INTERPOL), the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), the US Office of Naval Intelligence (UNI), and the Maritime Information Cooperation and Awareness Centre (MICA), have been actively collecting data at the international level. Similarly, regionally-focused centres, such as ReCAAP, the Information Fusion Centre (IFC) in Singapore, the Regional Maritime Information Fusion Centre (RFIMC) in Madagascar, the European Union Naval Force Operation Atalanta, the United Kingdom Maritime Trade Operations (UKMTO), the Maritime Security Centre – Horn of Africa (MSCHOA), the Information Fusion Centre-Indian Ocean Region (IFC-IOR), and the Marine Domain Awareness for Trade – Gulf of Guinea (MDAT-GoG), contribute significantly to the comprehensive data collection efforts.

It is evident that numerous organisations are actively collecting data, and since the advent of the current century, the number of such entities has increased significantly. In the realm of maritime security, the formulation of effective policies and responses relies heavily upon raw data. However, there are a series of questions that come to mind: to what extent can this amassed data be harmonised? Does it truly meet the diverse needs of all stakeholders, including law enforcement agencies, the shipping industry, security analysts, and coastal communities? Is there a comprehensive and overarching understanding provided to these entities?[37] The inherent deficiency in this gathered data lies in its reliance upon the quantitative analysis of figures, rather than trying to present a profound comprehension of the underlying implications of these figures. The compiled reports channel their analysis with a focus on the needs of commercial companies, while largely ignoring sea-land linkages and networks. Not just maritime piracy but the wider spectrum of the maritime crime needs data diversification by factoring terrorists, extremists, and State-sponsored non-State actors, and the violence perpetrated by them within the maritime domain.

Maritime domain awareness (MDA) is defined by the IMO as “the effective understanding of anything associated with the maritime domain that could impact security, safety, the economy or the marine environment”.[38] This concept is categorised into three types of awareness, namely, ‘military’, ‘non-military’, and ‘information-sharing mechanisms’, based on the actors involved and the nature of the information. Within the category of information-sharing, data is typically collected to meet the requirements of navies, countries, regional entities, and other stakeholders. This data collection follows a systematic process involving observation, collection, fusion, display, analysis, dissemination, and action. Maritime threats are monitored by recording the number and type of incidents at sea. The comprehensive fusion of data to enhance understanding of a specific area or situation within the maritime domain is termed “maritime situational awareness” (MSA). Data for both, MDA and MSA is collected from a variety of sensors such as ground-based and seaborne radar; shipborne-, floating-, ground-based, and satellite- and pseudo-satellite-based Automatic Identification Systems (AIS), remote-sensing satellites, electronic intelligence satellites, etc. Regionally, data on threats is processed by security frameworks and information fusion centres. In the Western Indian Ocean, several collaborative frameworks are actively monitoring various types of maritime crime. For instance, the Djibouti Code of Conduct – Jeddah Amendment (DCoC-JA) has significantly contributed to enhancing maritime situational awareness by encouraging its member-States to utilise technologies such as terrestrial AIS, long-range identification and tracking (LRIT), coastal radars, and other relevant sensors. Data generated by these efforts is disseminated through three Information Sharing Centres (ISCs) located in Dar-es-Salaam (Tanzania), Mombasa (Kenya), and Aden (Yemen).[39]

As part of the planned implementation of the maritime security framework in the Western Indian Ocean (WIO), the Regional Maritime Information Fusion Centre (RMIFC) in Madagascar and the Regional Coordination Operations Centre (RCOC) in Seychelles have been established. The primary aim of the RMIFC is to operate an automated real-time system for collecting, processing, displaying, analysing, and sharing maritime data, thereby providing continuous oversight of regional maritime activities for monitoring and surveillance purposes. To achieve this, the RMIFC utilises as its principal software application, the “Platform for Fusion for Maritime Information System” (PFMIS), also known as the “Maritime Awareness System” (MAS), capable of automatically handling large volumes of data and processing, correlating, visualising, and analysing information that is superimposed upon high-resolution digital ocean maps. The analysed data is then transmitted to the RCOC in Seychelles for decision-making on further actions. The core objective of constructing and regularly updating the Combined Regional Maritime Picture (CRMP) and thus the Maritime Security Architecture (MSA) is to facilitate evidence-based decision-making for precise and targeted actions at sea by the RCOC and its stakeholders.[40] While both centres acknowledge the evolving nature of sea-based threats, their current approach focuses on tracking the incidence of sea-based incidents, without yet incorporating any meaningful analysis of land-based factors driving these crimes.

Conclusion

Creating a risk profile for any given country aids in the development of a comprehensive picture of potential or real insecurity within a region. This process emphasises land-based, airborne, space-based, and sea-based factors, which taken in aggregate, cause or contribute to the emergence of maritime threats. The Western Indian Ocean holds a pivotal position in maritime geography, serving as a strategic gateway to the western segments of not only the Indian Ocean (IO) but also the broader Indo-Pacific. This heterogeneous and predominantly maritime expanse is located between Asia and Africa. Its western extremity encompasses critical chokepoints such as the Strait of Hormuz, the Strait of Bab-al-Mandeb, the Suez Canal, and the Mozambique Channel. This strategic maritime space reflects the geopolitical and geoeconomics aspirations not only of the States along the Indian Ocean rim and the island-States located within it, but also those of the international community at large, given that international shipping traverses this region. To safeguard this universally important maritime space, unconventional means of maritime security, which can leverage the game-changing potential of technology driven application, need to be employed.

Data, in and of itself, provides countries with the capacity to enhance their security efforts. However, data synthesis requires a capability that is not uniformly distributed across the world. Moreover, not all countries face identical maritime security threats. The data generated by the tools employed must cater to the needs of specific stakeholder communities, even while it must remain relevant to all stakeholders. Eastern African States and the WIO collective grapple with several maritime non-traditional threats that often originate on land. Is there a mechanism in place to bridge the data gap by integrating land-based information with that generated by maritime domain or situational awareness digital tools? Is it possible for maritime risk profiling to become a reality? These are questions that must be asked and answered by members of the security community of the WIO or those of the broader Indian Ocean.

******

About the Author

Ms Anum Khan is an Associate Fellow at the National Maritime Foundation. Her research is centred upon the multiple maritime facets of the eastern African littoral, about which she is discernibly passionate. She may be contacted at amgs2.nmf@gmail.com

Endnotes:

[1] Vice Admiral Pradeep Chauhan, “Overview of Maritime Geopolitics”, Internship Lecture at the National Maritime Foundation.

[2] Kelly Moss et al, “Stable Seas – Rethinking Maritime Security”, “Stable Seas: Western Indian Ocean”, One Earth Future, March 2022, 7.

[3] Barry J Ryan, “Maritime Security in a Critical Context”, in Routledge Handbook of Maritime Security, eds Ruxandra-Laura Boşilcă, Susana Ferreira, and Barry J Ryan, (New York: Routledge, 2022), 34.

[4] Federico Negro, “Selected Definitions and Characteristics of ‘Fragile States’ by Key International Actors”, International Labour Organisation. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—edemp/documents/terminology/wcms_504528.pdf.

[5] Jay Benson, “Violent Non-State Actors in the Maritime Space: Implications for the Philippines” Stable Seas, 07 January 2021, https://www.stableseas.org/post/violent-non-state-actors-in-the-maritime-space-implications-for-the-philippines.

[6] Meghan Curran, et al, “Violence at Sea: How Terrorists, Insurgents, and Other Extremists Exploit the Maritime Domain,” One Earth Future, August 2020, file:///Users/AnumKhan/Downloads/violence-at-sea%20(4).pdf.

[7] Marcus Lu, “Mapped: How Houthi Attacks in the Red Sea Impact the Global Economy,” Visual Capitalist, 19 December 2023, https://www.visualcapitalist.com/mapped-houthi-attacks-impact-economy/.

[8] Note: The Stable Seas program has devised the ‘Five Ts’ typology to provide a framework for enhancing the understanding of how and why violent non-State actors exploit the maritime space worldwide.

[9] John CK Daly, “Terrorism and Piracy: The Dual Threat to Maritime Shipping”, The Jamestown Foundation, 15 August 2008, https://jamestown.org/program/terrorism-and-piracy-the-dual-threat-to-maritime-shipping/.

[10] Wesley Wark, “The New World of Surveillance” in The 9/11 Effect and the Transformation of Global Security, Council of Foreign Relations, 01 September 2021, https://www.cfr.org/councilofcouncils/global-memos/911-effect-and-transformation-global-security.

[11] “Number of Armed Conflicts: World”, Our World in Data, https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/number-of-armed-conflicts.

[12] Ibid

[13] “UCDP GED Map: Active State-based Conflicts in 2022, based on UCDP 23.1 Data, Uppsala Conflict Data Program”, Uppsala University, 21 September 2023, https://ucdp.uu.se/downloads/charts/.

[14] Robert I Rotberg, “Failed States, Collapsed States, Weak States: Causes and Indicators” in State Failure and State Weakness in a Time of Terror, ed Robert I Rotberg, (Washington: Brookings Institution Press, 2003), 1-25.

[15] Data and Analysis, “The Afghan Opiate Trade Project”, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/data-and-analysis/aotp.html.

[16] Dryad Global, “High Risk Areas (HRA)-Designated Risk Areas – Arbitrary Lines or Useful Tools for the Illustration of Risk?”, May 2021, https://www.dryadglobal.com/high-risk-areas-and-maritime-war-risk-metis-insights.

[17]ACLED Conflict Index, “Ranking Violent Conflict Levels Across the World,” ACLED, January 2024, https://acleddata.com/conflict-index/.

[18] Uppsala Universitet, “Uppsala Conflict Data Program Department of Peace and Conflict Research,” 2023,

[19] Institute for Economics & Peace, “Global Terrorism Index 2024: Measuring the Impact of Terrorism”, Sydney, February 2024, https://www.visionofhumanity.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/GTI-2024-web-290224.pdf.

[20] Ediye Bassey, “Fragile States Index Annual Report 2023,” Fund for Peace, 2023, https://fragilestatesindex.org/2023/06/14/fragile-states-index-2023-annual-report/.

Note: The Fragile State Index categorises countries into a matrix ranging from very sustainable to very high alert based on their scores. The categories include sustainable, very stable, most stable, stable, warning, elevated warning, high warning, alert, and high alert.

[21] “YCO Home,” Yemen Conflict Observatory, ACLED, selected data range from 2022 to 2024, https://acleddata.com/yemen-conflict-observatory/.

[22] Kirk Moore, “Former US Navy HSV-2 Swift Wrecked in Yemen Missile Attack”, Workboat, 07 October 2016, https://www.workboat.com/bluewater/hsv-2-swift-wrecked-yemen-missile-attack.

[23] Luca Nevola, “Why Are Yemen’s Houthis Attacking Ships in the Red Sea?”, ACLED Database, 05 January 2024, https://acleddata.com/2024/01/05/qa-why-are-yemens-houthis-attacking-ships-in-the-red-sea/.

[24] “US, UK Bomb Houthi Sites in Yemen Amid Surge in Red Sea Ship Attacks”, Al Jazeera, 25 February 2024, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/2/25/us-uk-bomb-houthi-sites-in-yemen-amid-surge-in-red-sea-ship-attacks.

[25] “Analysis: Somalia Criminality Score,” Africa Organised Crime Index, 2023. https://africa.ocindex.net/country/somalia,

[26] EU NAVFOR-OP ATALANTA, “Maritime Piracy SITREP: Gulf of Aden/Somali Basin”, 08 February 2024, https://acrobat.adobe.com/id/urn:aaid:sc:AP:425aea12-0a1b-4add-bf16-a1a651407af4.

[27] Jacob Zenn, “Al-Shabaab versus the Islamic State”, Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses 15, No 2 (March 2023), 7-11, https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/48718086.pdf?.

[28] Meghan Curan et al, Stable Seas Program, “Violence At Sea: How Terrorists, Insurgents, and Other Extremists Exploit The Maritime Domain, One Earth Future, August 2020, 120, https://www.stableseas.org/post/violent-non-state-actors-in-the-maritime-space-implications-for-the-philippines.

[29] Samantha D Farquhar, “When Overfishing Leads to Terrorism: The Case of Somalia”, World Affairs: The Journal of International Issues 21, No 2 (Summer (April-June) 2017), 68-77.

[30] “Impact of Civil War on Natural Resources: A Case Study for Somaliland”, Candlelight for Health, Education & Environment, March 2006, https://land.igad.int/index.php/documents-1/countries/somalia/conflict-4/878-impact-of-civil-war-on-natural-resources-a-case-study-for-somaliland/file

[31] Ibid

[32] Ibid, 76.

[33] “From Suppliers to Scapegoats: Yemeni Fishers in Somali Waters at the Height of Piracy”, One Earth Future, https://oneearthfuture.org/en/secure-fisheries/news/suppliers-scapegoats-yemeni-fishers-somali-waters-height-piracy.

[34] Joseph Hanlon, “Mocimboa Da Praia Town and Port Captured by Insurgents,” Club of Mozambique, 14 August 2020, https://clubofmozambique.com/news/mocimboa-da-praia-town-and-port-captured-by-insurgents-by-joseph-hanlon-168768/.

[35] BBC News, “Mozambique Gas Project: Total Halts Work after Palma Attacks”, 26 April 2021, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-56886085.

[36] Lydelle Joubert, “What We Know About Piracy,” Stable Seas Program & Safe Seas Network, May 2020, 1-10, https://www.safeseas.net/what-we-know-about-piracy/

[37] “Do We Have the Right Data to Fight Maritime Piracy?”, Safe Seas & Stable Seas YouTube video, 7:15-19:16, 16 January 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7hUDxKJ8Hew&t=1273s.

[38] “Enhancing Maritime Domain Awareness in West Indian Ocean and Gulf of Aden”, IMO Media Centre, 14 November 2018, https://www.imo.org/en/MediaCentre/Pages/WhatsNew-1203.aspx

[39] “What Do We Do,” Information sharing Centre, Djibouti Code of Conduct, 17 April 2024, https://dcoc.org/information-sharing/.

[40] Indian Ocean Commission, “Maritime Security Architecture of the Western Indian Ocean”, 25 May 2022, file:///Users/AnumKhan/Downloads/2.WIO%20Maritime%20Security%20Architecture_Systems%20(1).pdf.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!