Abstract

In recent years, growing Chinese assertiveness in the South China Sea has been a source of increasing discomfiture, particularly, for those south-east Asian countries — as also Taiwan — which have a long-standing dispute over territorial sovereignty and associated maritime claims in the region. India, on its part, finds great commonality of interest with these countries over its long-held and consistent position on the ‘freedom, openness and inclusivity’ of the Indo-Pacific — of which the South China Sea forms a vital sub-region. India as an important stakeholder, and a likely affected party by the possible disruption of its trade lifeline through the South China Sea and connected seas, must look afresh at the maritime facets of its ‘Look East’ policy. India is accordingly seeking to overcome its customarily diffident external outlook, in promoting engagement with the South China Sea littorals, which stand to be similarly affected by the propensity of a revisionist power to unilaterally change the status-quo in a ‘zero-sum’ game of sorts. This nuanced ‘change of tack’ on India’s part is indeed apparent from certain foreign policy initiatives of recent past, in the region.

Keywords: Arbitral Tribunal Award-2016, ASEAN, China, Indo-Pacific, NMF, Philippines, Scarborough Shoal, South China Sea, TAEF, Taiwan

The 5th meeting of India-Philippines Joint Commission on Bilateral Cooperation (JCBC) jointly chaired by the foreign ministers of India and the Philippines in June 2023 generated quite a lot of interest in the global media.[1] The joint statement released after that meeting mentioned that “both countries have a shared interest in a free, open and inclusive Indo-Pacific region. They underlined the need for peaceful settlement of disputes and for ‘adherence’ to international law, especially the UNCLOS and the 2016 Arbitral Award on the South China Sea …”[2]

Some geopolitical analysts — who perennially keep a hawk-eye for proverbial ‘straws in the wind’ — raised a question whether India had ‘subtly’ changed its stance vis-à-vis its earlier articulated position, when the Arbitral Tribunal’s award on South China Sea was pronounced in 2016. The non-committal position of New Delhi at that time was quite apparent from its official response, wherein the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) stated that “India has noted the award of the Arbitral Tribunal constituted under Annex VII of the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of Sea (UNCLOS) in the matter concerning the Republic of the Philippines and the People’s Republic of China”.[3] The statement, without naming any country, further elaborated that “… States should resolve disputes through peaceful means without threat or use of force; and exercise self-restraint in the conduct of activities that could complicate or escalate disputes affecting peace and stability”.[4]

Background

The long-standing dispute between the Philippines and China in the South China Sea involves conflicting claims over various islands, islets, reefs, and shoals, which lie within the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of Philippines, but also fall inside the ‘unilaterally declared’ Chinese ‘nine-dash line’. China particularly chose to adopt an increasingly confrontationist posture around the Scarborough and Second Thomas shoals; with the Chinese fishing fleet, maritime militia vessels, and coast guard ships, systematically blocking, obstructing, and harassing the legitimate activities of the Philippines’ maritime community.

In response to China’s proactive assertion of its claimed historic and sovereign rights over such features — and unable to withstand the blatant Chinese coercion in contravention of existing conventions — Philippines filed for arbitration under Annex VII of UNCLOS in 2013. In July 2016, the Arbitral Tribunal issued an award favouring the Philippines submission; and urged China to respect other States’ sovereign rights. The Tribunal ruled that:[5]

- Maritime areas of the South China Sea encompassed by the ‘nine-dash line’ are contrary to the Convention and without lawful effect.

- China has violated the sovereign rights of the Philippines over various features within that country’s EEZ.

- China has breached its obligation with respect to the protection and preservation of the marine environment in the South China Sea.

The Tribunal also declared that Scarborough Shoal, Johnson Reef, Cuarteron Reef, Fiery Cross Reef, Gaven Reef (North) and McKennan Reef were high-tide features; while Subi Reef, Hughes Reef, Mischief Reef, and Second Thomas Shoal were ‘low tide elevations’ in their natural condition. While China refused to recognise the award, the country nonetheless progressively reduced its usage of the phrase ‘nine-dash line’ in its public pronouncements and official submissions; replacing it with the Government-legislated ‘SanSha’ geographical construct.

While Philippines is one of the disputants in the South China Sea, other South-east Asian countries which are adversely affected to different degrees by the Chinese assertion of ‘absolute sovereignty’ over the maritime area encompassing the so-called ‘Nine Dash Line’ are Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Brunei. Even though China claims Taiwan to be its own province the latter also has territorial sovereignty claims in the area. Some Chinese officials have tried to consolidate the idea of ‘indisputable sovereignty’ by referring to the encompassed area as the country’s ‘blue national soil’ — a phrase used to refer to the country’s offshore waters.[6]

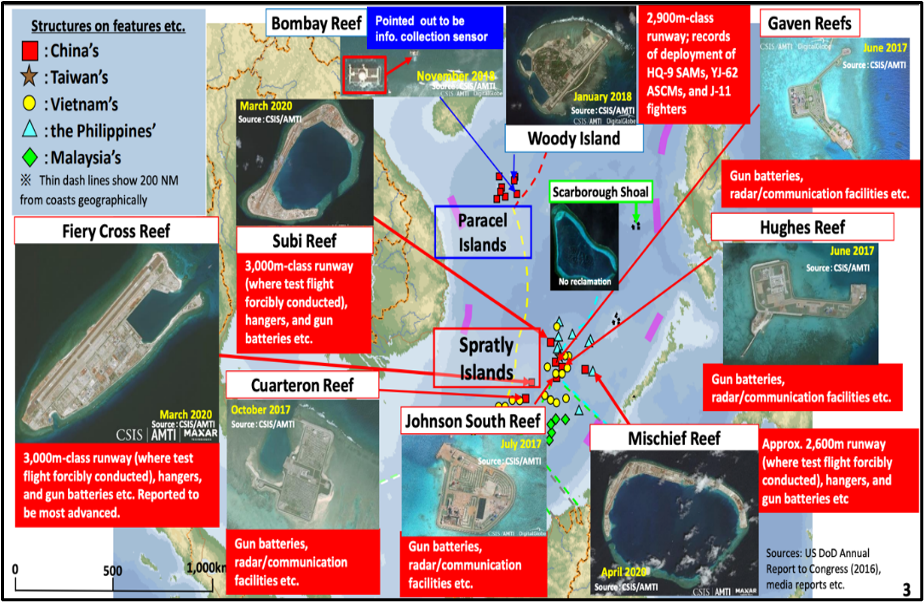

This dispute is becoming increasingly irreconcilable, with claimant States adopting a non-negotiable stance in recent years. Meanwhile, China continues to bolster its military presence in the South China Sea, having built seven artificial islands, with 3000+ metre-long airfields on three of them. It has also installed military equipment like aircraft hangars, radar stations, missile batteries, and gun emplacements on these islands. Japan’s Ministry of Defence has collated the details of such islands and the Chinese infrastructure development therein.[7] The same is depicted as a graphic at Figure 1.

Figure 1:China’s Occupation in the South China Sea after Reclamation

Source: Japan Ministry of Defence

Philippines-India Maritime Cooperation

In recent years, the relationship between India and Philippines has witnessed an upward trajectory as part of India’s ‘Act East’ Policy. And one would not be far off the mark in positing that both nations are further enhancing their engagement in the face of distinct rise in undesirable Chinese influence in the region. Philippines is clearly alarmed about China’s aggressiveness in the South China Sea. On the other hand, India’s concern stems from the possibility of these disputes disrupting the ‘freedom, openness, and inclusivity’ of the Indo-Pacific — an issue that India has been consistently propagating for the last decade. The two countries have been working assiduously to expand their military and maritime security cooperation. In 2022, Philippines and India signed a deal for the acquisition, by the former, of BrahMos missiles — the first ever sale of this state-of-the-art ordnance.[8] BrahMos is a supersonic cruise missile that may be deployed from land, sea, or air platforms. This acquisition will certainly provide a substantial boost to the military capability of the Philippines.

Indian Navy ships have been regularly ‘showing the flag’ and calling at Manila Port for more than 25 years, as part of their ‘overseas deployments’ (OSD) to the Western Pacific Ocean. A representative list of recent ship visits is placed at Table 1.

| Year | Indian Navy Ships | Other Countries visited |

| 2014

(August) |

INS Shivalik | Singapore, Vietnam, Malaysia, China, Japan, South Korea |

| 2015

(October) |

INS Sahyadri | Vietnam |

| 2016

(30 May-3 June) |

INS Satpura and INS Kirch | Vietnam |

| 2017

(23 September) |

INS Satpura, INS Kadmatt | Singapore, Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia, South Korea, Japan, Brunei and Russia |

| 2021

(August) |

INS Ranvijay and INS Kora | Vietnam |

| 2023

(02-08 May) |

INS Delhi and INS Satpura | Singapore, Malaysia, Cambodia, Indonesia |

Table 1: Representative list of Indian Navy Ship visits to Philippines

Source: Authors (from various media reports)

Philippines and India have also conducted combined maritime exercises — both bilaterally and multilaterally — in recent years. Naval delegations from the Philippines have also been participating in the MILAN series of multilateral exercises hosted by India, with the most recent one being MILAN-2022 at Visakhapatnam. These exercises have served to increase the interoperability of the navies of India and the Philippines, as also other participating naval forces. In August 2021, the Indian Navy and the Philippines Navy conducted a ‘maritime partnership exercise’ in the West Philippine Sea. The operational exercises included anti-submarine warfare (ASW), surface warfare, and air defence (AD) manoeuvres. In May 2023, naval ships of both countries engaged each other within multilateral settings during the inaugural ASEAN-India Maritime Exercise (AIME) in the South China Sea. The exercise also included ships, aircraft and naval personnel from six other ASEAN nations.[9] In July 2023, yet another bilateral naval exercise was conducted in the Sulu Sea, which featured anti-piracy drills, search and rescue, and maritime domain awareness exercises.

Thus, the expanding military cooperation between India and Philippines is certainly a favourable development for both nations. It is an indication that the two nations are dedicated to working together, in order to rise to the maritime security challenges of the 21st century within the Indo-Pacific.

India’s Interaction with other Claimants in South China Sea

In addition to Philippines, India also has a vibrant set of ongoing interaction with other South-east Asian nations, all of which are affected to varying degrees by the Chinese aggressiveness in the South China Sea. Vietnam which, like India, shares a land border with China but has managed to delineate its maritime boundary in the Beibu Gulf, is nevertheless locked in overlapping territorial sovereignty and associated maritime zones claims in the Paracel and Spratly chains of islands.

India and Vietnam have a strong maritime cooperative engagement as part of their comprehensive political, military, and economic relations. These are of course, built upon their mutual national interests. This relationship has become stronger, particularly after the increased assertiveness of China in the Indo-Pacific, in the new millennium. In 2011, an Indian Navy Landing Ship, the Airawat, while transiting well within the Vietnamese EEZ, was challenged on radio, supposedly by the Chinese Navy thus: “You are entering Chinese waters”. This ‘non-incident’[10] spurred the Indian MEA to respond publicly by reiterating that “India supports the freedom of navigation in international waters, including in the South China Sea, and the right of passage in accordance with accepted principles of international law. These principles should be respected by all.”[11] Chinese maritime militia and coast guard ships have been regularly harassing the oil exploration ships and Vietnamese vessels engaged in other legitimate activities in Vietnam’s own EEZ. India’s major oil company, ‘ONGC Videsh’, which is engaged in exploration and exploitation of offshore blocks assigned by Vietnam, has also faced severe pressure tactics of the Chinese maritime agencies, albeit sporadically.[12]

There is, thus, a natural compulsion for both the countries — particularly their navies—to actively cooperate and collaborate with one another in the interest of an ‘open, free and inclusive’ Indo-Pacific. Accordingly, it has become an annual feature for Indian Navy ships to visit one or another of Vietnam’s ports, during which they also participate in bilateral naval exercises with their counterparts. Personnel of the Vietnam Navy have been receiving regular naval operational and engineering training in India, including in specialised fields like aviation and submarine operations. The transfer of a fully operational missile corvette, the Kirpan, to Vietnam in July of 2023 — by the Chief of the Naval Staff, Admiral R Hari Kumar, during his visit to that country — was the latest and the most significant demonstration of close ties between the two navies.[13] It is thus posited that India’s maritime security — even in its primary areas of maritime interest, viz. the Indian Ocean — would be well served to a large extent by leveraging these close maritime ties, as explained by the author in another article.[14]

Although Indonesia, Malaysia and Brunei do not have any sovereignty dispute over any of the features in the South China Sea, occasional Chinese activities in assertion of its own jurisdictional claims in certain areas which lie within the Chinese ‘nine-dash line’, are of grave concern to these countries. China often deploys its fishing fleet, militia vessels, and Coast Guard ships in close vicinity of the Natuna Islands, where the Indonesian offshore gas fields are located. Malaysia too is worried about the Chinese maritime activities near Swallow Reef in its EEZ. The rise in instances of infringement by Chinese government vessels off Luconia Shoal near the Sarawak coast — the most recent being the presence of the Haiyang Dizhi No. 8 survey ship for two weeks in June and July 2023[15] — is yet another contentious issue. Wary of a direct confrontation, ships of the Malaysian and Indonesian Navy have resorted to ‘shadowing’ of such Chinese vessels.[16]

On its part, India has been assiduously working with Malaysia and Indonesia to jointly address critical challenges such as maritime security, counter-terrorism, and other non-traditional threats in the maritime domain.[17] Indian naval ships regularly visit Malaysian and Indonesian ports and carry out bilateral exercises with their counterparts. The navies of India and Indonesia have also been conducting coordinated patrols since 2002 and institutionalised exercises since 2015. The first naval exercise between Malaysia and India was held in 2013, while the first combined air drills were conducted in 2016. The first ever ASEAN-India Maritime Exercise (AIME), conducted in the South China Sea in May 2023, saw the participation of INS Delhi and INS Satpura, along with naval ships from Indonesia and Malaysia — as also those from the Philippines, Brunei, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam.[18]

These exercises and other interactions have helped to increase the interoperability of the three nations’ forces, and have also conveyed a signal to the regional hegemon that India, along with like-minded South-east Asian nations, values mutual security, and is ready to safeguard its interests in the area. India has all along, expressed its support to the ASEAN members towards preservation of their ‘sovereignty and territorial integrity,’ vis-à-vis unilateral Chinese efforts to alter the status-quo in the South China Sea. It has been calling for “peaceful resolution of disputes through dialogue and adherence to international rules and laws,” as highlighted by the Indian Prime Minister, Shri Narendra Modi, while articulating India’s vision for the Indo-Pacific, during the 2018 Shangri La Dialogue.[19]

Looking Beyond ASEAN – Strengthening India-Taiwan Relations

Territorial sovereignty issues and excessive maritime zone claims in South China Sea are not limited to China and South-East Asian disputants only. Taiwan has its own share of territorial claims vis-à-vis China, in that it claims all the islands and features that China occupies and claims. However, these issues have been pushed into background, as Taiwan contends with a far greater challenge — that of a possible reunification push — from an increasingly belligerent China. The situation in the Taiwan Strait — particularly since the visit of Nancy Pelosi, speaker of the US House of Representatives, in August 2022 — stands precariously poised, with China resorting to ever-increasing brinkmanship using its naval ships and aircraft on a daily basis.

India’s interactions with Taiwan have been quite constrained, owing to its recognition of the ‘One China Policy’. However, this inhibition is slowly but surely waning. In recent years, India has adopted a more proactively open posture while engaging with Taiwan. India’s trade with Taiwan has expanded substantially in recent years. In 2022, the overall bilateral value of commerce was $12.5 billion, up from $10.5 billion in 2021, and $8.5 billion in 2020.[20] The investment of Taiwanese corporations in India — mainly in electronics and semi-conductor industries — have seen a significant uptick in recent years. In 2022, Taiwanese corporations committed $2.5 billion in India, up from $1.5 billion in 2021. Investments from Foxconn, Taiwan Semi-conductor Company (TSMC) and United Microelectronics Company (UMC) are helping to strengthen India’s semi-conductor manufacturing capacity; and also generating local employment.

In 2023, Taiwan announced its intention to establish a new cultural centre in Mumbai — the first two being in Delhi and Chennai. The centre will become fully functional in 2024. The new cultural centre in India’s commercial capital, will be a forum for enhancing financial and trade ties between the two countries, in addition to promoting cultural and economic exchanges.[21]

Even though both, India and Taiwan, recognise existing foreign policy constraints, they have, especially in recent years, shown the will to engage in preliminary discussions on the maritime security situation obtaining in the Indo-Pacific. Taiwan apparently identifies ‘think-tank diplomacy as the fifth pillar’ of its ‘New Southbound Policy (NSP)’ of 2016 for establishing regional connections. Accordingly, the Taiwan-Asia Exchange Foundation (TAEF), a think tank mandated to progress and publicise the vision of the NSP, entered into a three-year institutional partnership with India’s Observer Research Foundation in 2022.[22] The two think tanks also held the first Taiwan-India Dialogue in October 2022 to deliberate on the stability and security in the Indo-Pacific, the roles of Taiwan and India therein, and the prospects of their partnership.[23] TAEF also signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) on ‘maritime cooperation and regional development’ with the premier maritime security think tank of India, the National Maritime Foundation (NMF), in 2020.[24]

Taiwan has been offering language and academic fellowship courses in Taiwanese universities and other institutions to Indian students and scholars, thus preparing a ready pool of scholarly human resource, which can act as a vital geostrategic bridge between the two countries. Distinguished academics, geostrategic analysts, and senior retired service officers have occasionally been visiting Taiwan. Admiral Arun Prakash, former Chief of the Naval Staff and a renowned maritime strategist, avers that the recent visit of the three former Chiefs of Indian Armed Forces to Taiwan albeit in their individual capacities, and solely for academic deliberations, certainly signals mutuality of interest — though he hastens to add that this must not be overread.[25]

Conclusion

In recent years, growing Chinese assertiveness in the South China Sea has been a source of increasing discomfiture, particularly, for those Southeast Asian countries that have a long-standing dispute over territorial sovereignty and associated maritime claims in the region. Taiwan also grapples with an existential threat on account of increasingly tenuous situation in the Taiwan Strait. India, on its part, finds great commonality of interest with these countries over its long-held and consistent position on the ‘freedom, openness and inclusivity’ of the Indo-Pacific — of which the South China Sea forms a vital sub-region. Peace and stability in the area, as also in the Taiwan Strait, is essential for the unimpeded flow of seaborne energy and commerce, which in turn are so essential for the economic wellbeing of the world.

It is, therefore, high time that India, as an important stakeholder, as also a likely affected party by the possible disruption of its trade lifeline through the South China Sea and the Taiwan Strait, must look afresh at the maritime facets of its ‘Look East’ policy. It must accordingly ‘change tack’ and think of new and novel ways to promote engagement with other nations that stand to be similarly affected by the propensity of a revisionist power to unilaterally change the status quo in its favour; and to the consequent detriment of everyone else. And the subtle ‘change of tack’ — a sailing term that implies a decisive change of direction — on India’s part is indeed quite apparent from the few instances cited above.

Views expressed in this article are personal and attributable solely to the authors themselves.

*****

About the Authors:

Captain Kamlesh K Agnihotri, IN (Retd.) is a Senior Fellow at the National Maritime Foundation (NMF), New Delhi. His research concentrates upon maritime facets of hard security vis-à-vis China and Pakistan. He also focuses upon maritime security issues related to the Indo-Pacific Region. He can be reached at kkumaragni@gmail.com

Mr. Nirmal Shankar M holds a master’s degree in international relations from Pondicherry University. His areas of study include the power politics of West Asia and Israel. The traditional and non-traditional issues in the Indo-Pacific region also interest him. He has just completed a six-month research internship at the National Maritime Foundation (in August 2023). He may be reached at nirmalshankarmani04@gmail.com

[1]Lariosa, Aaron-Matthew. 2023. “India Revises Stance on China-Philippines Maritime Dispute as New Delhi Looks East”, USNI News, 05 July 2023, https://news.usni.org/2023/07/05/india-revises-stance-on-china-philippines-maritime-dispute-as-new-delhi-looks-east.

[2]India’s Ministry of External Affairs, “Joint Statement on the 5th India-Philippines Joint Commission on Bilateral Cooperation.” 29 June 2023, https://mea.gov.in/bilateral-documents.htm?dtl/36743/ Joint_Statement_on_the_5th_IndiaPhilippines_Joint_Commission_on_Bilateral_Cooperation.

[3]India’s Ministry of External Affairs, “Statement on Award of Arbitral Tribunal on South China Sea under Annexure VII of UNCLOS”, 12 July 2016, https://www.mea.gov.in/press-releases.htm?dtl/27019/ statement+on+award+of+arbitral+tribunal+on+south+china+sea+under+annexure+vii+of+unclos.

[4]Ibid.

[5] Permanent Court of Arbitration, “PCA Case No. 2013-19 In the matter of the South China Sea Arbitration”, 12 July 2016, pp. 473-76, https://docs.pca-cpa.org/2016/07/PH-CN-20160712-Award.pdf

[6] James R. Holmes, “The Commons: Beijing’s ‘Blue National Soil”, The Diplomat, 03 January 2013. https://thediplomat.com/2013/01/a-threat-to-the-commons-blue-national-soil/#:~:text=Beijing%20defines%20offshore%20waters%20as,exercise%20within%20their%20land%20frontiers..

[7] Japan Ministry of Defence, Presentation on “China’s Activities in the South China Sea (China’s development activities on the features and trends in related countries)”, 08 February 2023, https://www.mod.go.jp/en/d_act/sec_env/pdf/ch_d-act_b_e_230208.pdf

[8] Press Information Bureau, “BrahMos Signs Contract with Philippines for Export of Shore Based Anti-Ship Missile System.” 28 January 2022, https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1793209.

[9] Press Information Bureau, “Sea Phase of ASEAN-India Maritime Exercise – 2023, 09 May 2023, https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1922815#:~:text=The%20inaugural%20ASEAN%20India%20Maritime,of%20the%20multilateral%20naval%20exercise.

[10] The Author has used this phrase to connote the fact that no Chinese ship was seen in the vicinity, and the Indian Navy ship continued on its pre-scheduled route without any hindrance.

[11] Ministry of External Affairs, “Incident involving INS Airavat in South China Sea”, 01 September 2011, https://www.mea.gov.in/media-briefings.htm?dtl/3040/Incident+involving+INS+Airavat+in+South+China+Sea

[12] The EurAsian Times, “Vietnam Cautions India on Chinese Disruption of ONGC’ Oil Exploration Projects in South China Sea”, 30 July 2019, https://www.eurasiantimes.com/vietnam-cautions-india-on-chinese-disruption-of-ongc-oil-exploration-projects-in-south-china-sea/

[13] Press Information Bureau, “Handing Over of Ins Kirpan to VPN”, 22 July 2023, https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1941807

[14] Kamlesh K Agnihotri, Apila Sangtam, Khath Bunthorn, “Ream Naval Base Upgrade Project in Cambodia: New Point for Geopolitical Contestation in the Indo-Pacific”, National Maritime Foundation Website, 08 October 2022, https://maritimeindia.org/ream-naval-base-upgrade-project-in-cambodia-new-point-for-geopolitical-contestation-in-the-indo-pacific/

[15] Malaysia Military Times, “Chinese Research Vessel, Haiyang Dizhi 8 is in Malaysia’s EEZ Waters for Two Weeks”, 06 July 2023, https://mymilitarytimes.com/index.php/2023/07/06/chinese-research-vessel-haiyang-dizhi-8-is-in-malaysias-eez-waters-for-two-weeks/

[16]Emirza Adi Syailendra, “China, Indonesia, and Malaysia: Waltzing around Oil Rigs”, The Diplomat, 18 August 2022, https://thediplomat.com/2022/08/china-indonesia-and-malaysia-waltzing-around-oil-rigs/.

[17]Granados, Ulises, “India’s Approaches to the South China Sea: Priorities and Balances”, Asia & the Pacific Policy Studies, Vol. 5, Issue 1, 122–137, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/app5.223

[18] Press Information Bureau, “Sea Phase of ASEAN-India Maritime Exercise – 2023 ibid.

[19] Press Information Bureau, ‘Text of Prime Minister’s Keynote Address at Shangri La Dialogue’, 01 June 2018, https://pib.gov.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=179711

[20] Invest India, “India-Taiwan Relations”, https://www.investindia.gov.in/country/taiwan-plus.

[21] Taipei Economic and Cultural Center in India, “Republic of China (Taiwan) to Establish Taipei Economic and Cultural Center in Mumbai to Further Advance Substantive Ties with India,” 05 July 2023, https://www.roc-taiwan.org/in_en/post/6311.html.

[22] Alan Yang, Sana Hashmi, “Think tanks are leading Taiwan’s overseas outreach from the front,” The Sunday Guardian, 02 October 2022, https://sundayguardianlive.com/news/think-tanks-leading-taiwans-overseas-outreach-front

[23] The Yushan Forum, “Inaugural Taiwan-India Dialogue, Exploring Avenues for Deepening Bilateral Ties”, Press Release, 11 October 2022, https://www.yushanforum.org/news.php?id=1082

[24]Lu Yi-hsuan and Jake Chung “Taiwan, Indian Think Tanks Sign Cooperation Deal.” Taipei Times, 09 October 2020. https://www.taipeitimes.com/News/taiwan/archives/2020/10/09/2003744869.

[25] Arun Prakash, “Delhi and Taipei, just friends”, The Indian Express, 14 August 2023, https://indianexpress.com/ article/opinion/columns/india-taiwan-relation-military-operations-chinese-domination-us-confrontation-with-beijing-8891136/

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!