Abstract

Africa’s Integrated Maritime (AIM) Strategy, 2050, was promulgated by the African Union (AU) in 2012 as a pan-African maritime strategy document. The maritime outlook of Africa, as reflected in the 2050 AIM Strategy, spans a heterogeneous ocean territory that comprises the Atlantic Ocean to the continent’s west, the Mediterranean Sea to its north, the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean to its east, and the blending waters of the Atlantic and the Indian Ocean to its south. Metaphorically, it appears as a kaleidoscope of 54 strategies that constantly form patterns of solutions to the challenges faced by its varying actors on their respective maritime fronts. The vision statement adopted by the Strategy indicates that 2050 AIMS aims to “foster increased wealth creation from Africa’s oceans and seas by developing a sustainable, thriving blue economy in a secure and environmentally sustainable manner”. This must be viewed in the light of collective ‘Afro–optimism’ — envisioning a promising future catered by waters surrounding continental Africa. This paper seeks to explore and present lessons and intersecting solutions arising-from and lying-between the eastern shore of Africa and the broader Indo-Pacific. By synthesising the various elements of maritime security contained in this Strategy, the author hopes to create a cohesive picture of security imperatives present in east Africa’s Maritime Domain (AMD). As a result, a comprehensive yet Africa-centric account of ‘maritime security’ needs to first be established in order to understand the various forms of security practices being adopted in Africa’s Maritime Domain (AMD), which can contribute to the security of the Indo pacific.

Keywords

Africa’s Integrated Maritime (AIM) Security 2050; Indo-Pacific; Maritime Security, African Maritime Domain (AMD)

A nation’s maritime strategy may be described as a documented manifestation of the manner in which the nation concerned intends to pursue its interests and attain its stated as well as unstated policy-goals, contextualised to the maritime spaces that it views as being relevant to it. It is also a manner of strategic communication that lays down a broad course of action where the sea is a substantial factor.[1] A commonly followed trend of formulating these maritime strategies by nations is to explicitly state their geopolitical and politico-military goals within the narrative of the strategy. In such cases, their strategies are predominantly directed towards military objectives that the nation considers will facilitate the attainment of the economic goals that it strives to achieve from the ocean. In considering the 2050 AIM strategy it is important to bear in mind the caveat that the maritime strategy of a nation cannot be conflated with the maritime strategy of a continent! The latter will often reflect the minimum acceptable common features that define the strategy of the collective in question — the African Union in this case.

Africa’s Integrated Maritime (AIM) Strategy for 2050 was released by the African Union (AU) in 2012 as a pan-African maritime strategy document.[2] It covers the maritime outlook of Africa, which comprises a heterogenous oceanic space, incorporating the Atlantic Ocean to its west, the Mediterranean Sea to its north, the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean to its east, and the blended waters of the Atlantic and the Indian Ocean to the south. The strategy not only projects the AU’s perspective but also seeks to speak on behalf of the 54 African nations in a unified voice. Metaphorically, it may be seen as a kaleidoscope of 54 individual strategies, which form continuously changing patterns of solutions to address the challenges faced by the various actors on their respective maritime fronts. The vision statement enunciated in the Strategy is to “foster increased wealth creation from Africa’s oceans and seas by developing a sustainable thriving blue economy in a secure and environmentally sustainable manner”.[3] This must be viewed in the light of collective ‘Afro-optimism’ — envisioning a promising future shaped by the waters surrounding continental Africa. However, this optimism must necessarily be a guarded one, given the dire threats present around the continent. Consequently, if one is to even begin to understand the varied security practices being adopted in Africa’s Maritime Domain (AMD),[4] it is crucial to establish a comprehensive, Africa-centric account of ‘maritime security’.

This article focuses upon the ‘maritime security’ of the AMD and factors the various security stakeholders in the east African littoral space. Its purpose is to examine previously overlooked security perceptions by highlighting structures that have the potential to contribute to Africa’s aspirations in terms of maritime security. Within the complex network of non-African providers of security within the east African littoral space, it emphasises the critical need for the resident littoral States themselves to establish a sustainable response to the threats emanating from their territorial seas and exclusive economic zones.

Precepts of Africa’s Maritime Security – Securitization and Subsidiarity

‘Security’, ‘Securitization’, and ‘Subsidiarity’ are related concepts but with distinct and discrete applications. Within the broad sweep of the discipline of International Relations (IR), there has frequently been some contestation around the term ‘security’,[5] although it is now widely used across domains. ‘Maritime Security’, as highlighted by Christian Bueger, has become a ‘new buzzword’[6] but despite being viewed within a maritime context, it lacks a uniform definition. It is possible for security to be understood as the mere ‘absence of threats.’ However, this seems intuitively inadequate. In the maritime domain relevant to the eastern African littoral, security needs to be viewed in relation to maritime threats arising in the AMD. Within the 2050 AIM strategy, the segment relating to ‘maritime governance’ identifies ten maritime threats that afflict the AMD,[7] with several of them posing significant challenges within Africa’s eastern seaboard.

- From Securitization to Subsidiarity — Taking a Different Path to Security

‘Security’ is a handy term and is often misused without paying much heed to its applicability within a given context. In classical security approaches, the concept of ‘security’ encompasses the material and structural aspects of threats, including power distribution, military capabilities, and polarity. On the other hand, ‘securitization’ explores how an actor transforms a specific issue into a matter of security, frequently warranting the use of extraordinary measures. The concept of ‘securitization’ helps one to understand maritime threats by focusing on the ‘actors’ responsible for both insecurity and security. This is especially relevant to eastern African coastal and island States, where the maritime space is a fairly convoluted zone with a pervasive presence of a variety of actors, all seeking to ensure regional security.

- Africa’s Perception of Maritime Security and the Criticality of ‘Subsidiarity’

Section 8 of the 2050 AIM Strategy states that security is a subset of maritime governance and forms an indispensable component of the ‘blue-economy’.[8] Since the ‘blue-economy’ is the lynchpin of the strategy, the entire gamut of security has also been located within it. The 2050 AIM Strategy serves as a sort of Snell’s Window for maritime-security stakeholders, offering a perspective that seeks to eliminate deviation and promotes Africa-centricity. This notwithstanding, African centricity in terms building a security understanding also seems insufficient — it has to be brought to bear in terms of ‘security practice’, too. Security-driven maritime governance, then, is the key feature of the strategy, and to effectively implement it, past and existing approaches to Africa’s security need to be understood. This is where ‘subsidiarity’ plays an important role. ‘Subsidiarity’ is a principle according to which a “central authority should have subsidiary functions performing only those tasks which can’t be performed effectively at a more immediate or local level”.[9] While subsidiarity may well have remained understated in the AU’s charter, the Charter on Maritime Safety and Security and Development in Africa, the Lomé Charter is the only AU document that explicitly defines ‘subsidiarity.’[10] The Lomé Charter, by making subsidiarity a guiding principle, advocates freedom at the local level, thereby, implying the sharing of competence at different levels. The explicit acknowledgement and advocacy of the principle of subsidiarity makes Africa’s case unique and allows for the comprehensive evaluation of the contributions of Regional Economic Communities (RECs) to maritime security.

Understanding East Africa as a Risk-Prone Strategic Geography

Africa comprises 38 littoral States, with a combined coastline that stretches over 26,000 nm. The total area of the territorial seas and exclusive economic zones (EEZ) covers approximately 13 million square kilometres, while the consolidated legal continental shelf covers an area of approximately 6.5 million square kilometres.[11] These vast swaths of ocean endow Africa as a whole with very substantial wealth in terms of marine resources, diverse flora and fauna, fish stocks, minerals, and hydrocarbons. Africa’s seas and oceans are also conduits of vital trade, given that over 90% of its trade is seaborne. On the one hand, it is evident that this maritime posture of Africa serves it well in several ways. On the other, however, this vast oceanic exposure also makes it susceptible to a diverse yet substantive threats. Instability at sea could arise due to multiple factors, and to be able to successfully analyse these factors it is important to demarcate the maritime geography of the continent.

The maritime territory that falls under the purview of this paper is the eastern African littoral and the island States of the Indian Ocean, including the overseas territories of France (La Réunion and Mayotte). It stretches from Somalia to the southern tip of South Africa and encompasses Madagascar as well as the Small Island Developing States (SIDS) of Comoros, Mauritius, and Seychelles.[12] This littoral has a combined coastline of over 19,000 kilometres, dotted with a network of ports that act as trade gateways for both coastal and landlocked east African countries,[13] and generates significance geopolitical significance. While the Indo-Pacific as a strategic geography is recognised by an increasing number of States, not all of them include east Africa within its ambit. India, of course, has long been advocating that the expanse of its Indo-Pacific geography extends from the eastern shores of Africa to the western shores of the Americas.[14] Moreover, the entire lot of east African coastal States form a part of India’s ‘proximate maritime neighbourhood’ and are, therefore, an inherent part of New Delhi’s maritime security framework. India’s maritime security objectives, as outlined in its 2015 maritime security strategy entitled, “Ensuring Secure Seas: Indian Maritime Security Strategy”, encapsulate a set of objectives aimed at safeguarding the country’s principal maritime interest.[15] Amongst these several objectives, one that is quite explicitly stated is to “shape a favourable and positive maritime environment, for enhancing net security in India’s area of maritime interest.” India’s maritime interests are derived from the eight maritime objectives steered by its maritime policy, encapsulated by the acronym SAGAR, which expands to ‘Security and Growth for all in the Region’. Two of India’s prominent objectives are the imperative of stability in India’s maritime neighbourhood, and the promotion, protection, and preservation of India’s overseas and coastal seaborne trade and her Sea Lines of Communication (SLOCS). Therefore, stability in east African littoral- and island-States is of paramount importance to India.

East Africa’s Maritime Challenges

In the evolving maritime security paradigm, concerns over non-traditional maritime threats now match, if not exceed, anxieties over traditional ones. The seas are increasingly infested by a range of maritime threats that seriously threaten maritime stability and security. The waters off the coasts of east African States are, in fact, now plagued by a mix of both traditional and non-traditional threats, as a result of which any examination of the efficacy of the 2050 AIM strategy cannot be viewed through a monochromatic lens. The entire littoral stretch from Somalia to South Africa is embroiled in sporadic State-on-State violence characterised by diverse actors with varying degrees of agency, power, and tactical asymmetry. The ephemeral presence of violent non-State actors (VNSAs) such as the Al Shabab group in Somalia, compounds a danger that is fast spreading eastward, particularly in Kenya. Mozambique, too, is struggling with another Islamic insurgent group (the Ahlu Sunna Wal Jamaa [ASWJ] operating under the more generic name of Al-Shabab), whose modus operandi is quite similar to that of pirates. These ongoing State conflicts tend to spill into the maritime domain, creating rents in the security fabric of the east African littoral. In addition to State-on-State violence, the littoral also suffers from a variety of forms of transnational organised crime, including piracy, seaborne and coastal trafficking in narcotics, arms, and human beings, mixed migration, illegal oil bunkering, etc.[16]

The risk landscape of littoral east Africa has undergone significant changes since the year 2000. In 2009, piracy in the Horn of Africa, predominantly off the coast of Somalia, reached its peak. Although the severity of this threat has abated, its land-based origins remain unaddressed and, as a consequence, the threat still looms large.[17] The economic cost of piracy in 2017 amounted to $1.4 billion, resulting in a staggering cost having to be borne for the maintenance of for security, where almost $292.5 million went to privately contracted armed security personnel and almost $199.7 million was incurred as the cost of international naval activities.[18] Al Shabab, utilising a pirate-like revenue model, has been running an extortion and illicit taxation enterprise at the port of Mogadishu.[19] The “Stable Seas: Western Indian Ocean” report by One Earth has highlighted key findings from the region, categorising them into issue areas that accurately capture the threat spectrum of east Africa. According to this report, in 2022 large tracts of the east African shoreline were struggling with piracy and armed robbery at sea, drugs and wildlife trafficking, illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing, and climate change.

Due to the presence of a large number of fragile States along the east African belt, four primary migration routes exist in the region. As per the Fragile States Index Annual Report 2022 by the Fund for Peace, all east African littoral states come under one or another of the categories labelled ‘elevated warning’, ‘high warning’, ‘alert’ and ‘very high alert’.[20] Drugs and arms trafficking contribute significantly to the illicit trade network, further exacerbating endemic port vulnerability. According to the IUU-Fishing Index, overfishing, both leading to and resulting from IUU fishing, costs east African States up to approximately $19.8 billion, with Somalia and Seychelles being the worst-performing countries.[21] Yet, the 2050 AIMS is a ‘blue economy’ inclined document that aims to harness the region’s ocean potential to the fullest. The economic security of the region is not just hampered by terrorist activities in the region but also by climatic conditions. The stretch is experiencing severe climatic change, with the Horn (Somalia, Djibouti, Ethiopia, and Kenya) undergoing an unprecedented drought and harsh temperatures which, in 2022, affected nearly 13 million people by pulling them into a descending spiral of food insecurity.[22] Unfortunately, in any given situation, climate crises have snowballing effects, where one climate-led disruption leads to many consequent interventions that can create havoc in the area. In 2019, for example, the Indian Ocean experienced the largest number of cyclones on record, severely impacting Mozambique, and Madagascar. The cyclones did not just bring flooding in their wake, but the widespread and intense rainfall in hitherto dry areas such as the Empty Quarter (the Rub’ al Khali is the sand desert encompassing most of the southern third of the Arabian Peninsula) and Somalia brought about substantial increases in the number and density of swarms of desert locusts, which then ravaged crops on the land, adding to food insecurity.[23]

Assessing Foreign and Domestic Actors and their Agency

The persistent efforts of resident and non-resident navies are described in conceptual terms by Ken Booth in his book, “Navies and Foreign Policy,” where he has likened the functional roles of navies to the sides of a triangle incorporating military, diplomatic and policing (constabulary) roles.[24] This conceptual understanding adequately explains the presence of numerous navies or naval collaborations along the east African shoreline, as these navies perceive the maritime challenges faced by eastern African coastal States as being equally relevant to their own economic and non-geoeconomic maritime interests. To progress maritime connectivity in general and maritime merchandise trade in particular, International Shipping Lanes (ISL) — and their equivalent in times of international armed conflict, namely, ‘Sea Lines of Communication’ are crucial. Thus, the Western Indian Ocean (WIO), which is a geographically non-specific term often used to indicate the waters encompassing the east African littoral and the island States of Africa, is a theatre of geopolitics in which many actors have stakes.

As States — particularly those that have embraced independence relatively recently — wrestle with problems related to the manner in which maritime zones created by the UNCLOS (1982) ought best to be managed, a seemingly attractive option is the creation of Joint Management Zones. Thus the ‘Combined Exclusive Maritime Zones of Africa’ (CEMZA) represents the African vision of a common African maritime space — one without barriers. Although conceived as a ‘plan of action’ in the 2050 AIMS, this vision of African strategy does not align well with the maritime security practices being implemented by various actors in and off east Africa. Joint management zones present a paradox when it comes to militaries being deployed as an instrument for the eradication of seaborne threats. Since 2009, the WIO has seen a plethora of resident and non-resident navies, all determined to combat piracy and other forms of maritime crime, in the Gulf of Aden, as also in its proximity. This has led to the securitization of the Indian Ocean off the eastern African littoral. While the piracy and violent crime at sea validates the need for securitization, the persistence of suchlike threats indicates that this engagement is either insufficient or in need of structural updates.

Threats along and off the east African shoreline have not only diversified but have also shown tactical transformations, necessitating the mounting of an equally transformative defence. The geopolitics of security in the waters of east Africa has come to be defined by many disparate actors. France, with 20% of its EEZ located in the Southwestern Indian Ocean (SWIO), asserts that it is a resident Indian Ocean power.[25] Indeed, this is widely acknowledged as France is now a full-fledged member of all three major structural organisations of the Indian Ocean Region — the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA), the Indian Ocean Commission (IOC), and the Indian Ocean Naval Symposium (IONS). The USA and the EU, for their part, have created dedicated task forces and launched a number of naval operations to combat piracy and ensure more generalised good order at and stability across a swath from the Persian Gulf to the Arabian Sea extending to the waters off the Horn of Africa and southern Somalia. Combined Maritime Task Force 150, originally formed by the USA in 2006 to fight terrorism, remains in place to address contemporary and potential maritime instability, while Combined Task Force 151 and the EU Naval Forces ‘Operation ATALANTA’, which were originally sharply focused upon countering piracy in the Gulf of Aden and its maritime environs, have broadened their functional remit to one of ensuring stability and good order. India, too, has followed suit and, while maintaining its naval presence in the area that it first established in 2008, is no longer engaged solely in counter-piracy and escort missions through the internationally recognised transit corridor (IRTC) but instead, is contributing to maritime stability in the area by escorting ships of the World Food Programme and, as an ‘Associate Partner’ within the CMF, participates in CMF missions, including exercises involving the USA’s combatant command (COCOM) in Africa (‘AFRICOM’). Disconcertingly for many, China, too, is maintaining, without a break, the naval presence that it established in 2008 to combat piracy.[26] To logistically support these naval deployments, as also more land-centric ones, Djibouti has been selected by a number of countries (eight at last count!) as a support base. The securitization of the exclusive economic zones of a number of littoral States of eastern Africa, is quite evident — the current foreign maritime security architecture off the east African coast is spearheaded by a combination of intergovernmental and governmental organisations. These include, inter alia, the ‘Combined Maritime Forces’ (CMF), the ‘European Union Naval Force Somalia’ (Operation ATALANTA), the ‘European Union Capacity Programme in Somalia’ (EUCAP-Somalia), the Africa-centric ‘Intergovernmental Authority on Development’ (IGAD), the ‘Indian Ocean Commission’ (IOC), INTERPOL, INTERPORTPOLICE, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), the United Kingdom Marine Trade Operations (UKMTO), etc. — not to mention a slew of ‘maritime domain awareness’ (MDA) portals and programmes ranging from India’s MSIS, to the EU’s CRIMARIO-2, the USA’s MSSIS and CENTRIX, and a host of others.

However, in several of these non-African maritime-security frameworks, east African coastal and/or island States have only token representation, and the active participation of their maritime security forces is minimal. This is not to say that the presence of foreign maritime security initiatives in the proximity has not positively contributed to the building of capacity and enhancement of capability within east African littoral and island States. The Maritime Security in Eastern and Southern Africa (MaSé) programme, which is solely funded by the EU but implemented by IGAD, COMESA, EAC, and the IOC, is intended to enhance the resilience of regional States and has certainly helped the latter prepare a strategy and action plans to improve their individual and collective maritime security. Nevertheless, it is clearly desirable for eastern Africa (and Africa more generally) to have an efficient maritime security architecture of its own in place. The Djibouti Code of Conduct (Jeddah Amendment) [DCoC (JA)] is a good example. Although it was conceptualised by the International Maritime Organisation (IMO), the DCoC-JA has a predominant presence of African States and has been instrumental in the maintenance of stability and good order at sea off the African coast. It, too, has revamped its functional structure in recognition of the fact that while piracy as the most immediate and visible threat the maritime security might well have been suppressed, other forms of maritime crime remain rampant. Thus, the 2017 Jeddah Amendment to the DCoC has included all contemporary maritime threats that are active (or could become so) along and off the coast of eastern Africa.[27] A major positive result of is that every DCoC (JA) signatory state has established (or is in the process of establishing) a ‘National Maritime Security Committee’ to oversee the operationalisation of a ‘National Maritime Information Sharing Centre’ (NMISC). Thus, in the heavily securitized maritime space off the east African coast, resident domestic State actors are, indeed, asserting that they do have agency. It is for the plethora of international actors to strengthen this African agency rather than simply imposing their own.

Maritime Security Governance Architecture of Africa

The focus of the 2050 AIM Strategy is to harness ocean wealth for the sustainable economic development of the African people. African States are acutely aware of the importance of the oceans, and the African Union has declared 2015-2025 to be the decade of “African Seas and Oceans”, with the objective of harnessing the ‘blue economy’ to achieve the African Union Agenda 2063. A range of African initiatives incorporate a clear maritime dimension. Similarly, Agenda 2063, a pan-African transformational vision adopted in 2013, aims to accelerate the economic growth in its ‘Goal 6’ through the blue economy by focusing on marine resources and energy, port operations, marine transport, and the sustainable management of natural resources along with conservation of Africa’s rich biodiversity — including its marine biodiversity. A number of African ‘Regional Economic Community’ (REC) structures have maritime security action plans nested within their agendas. Therefore, for the successful implementation of Africa’s ‘Blue Wall Initiative’ — “an Africa-led effort toward a nature-positive world that enhances the planet’s and societies’ resilience to halt and reverse nature loss by 2030. It aims to create interconnected, protected, and conserved marine areas to counter the effects of climate change and global warming in the Western Indian Ocean (WIO) region.”[28] — a process-based maritime-governance model must be put in place. The implementation plan for such a model of ocean governance) can be synthesised from the African Union’s ‘Agenda 2063’, ‘Africa’s Integrated Maritime Strategy’ (2050 AIMS) of 2012, the 2014 ‘Policy Framework and Reform Strategy for Fisheries and Aquaculture in Africa’ (PFRS), the 2015 ‘UN Agenda 2030’ (Sustainable Development Goals), and the 2016 ‘African Charter on Maritime Security and Safety and Development in Africa’ (Lomé Charter).[29]

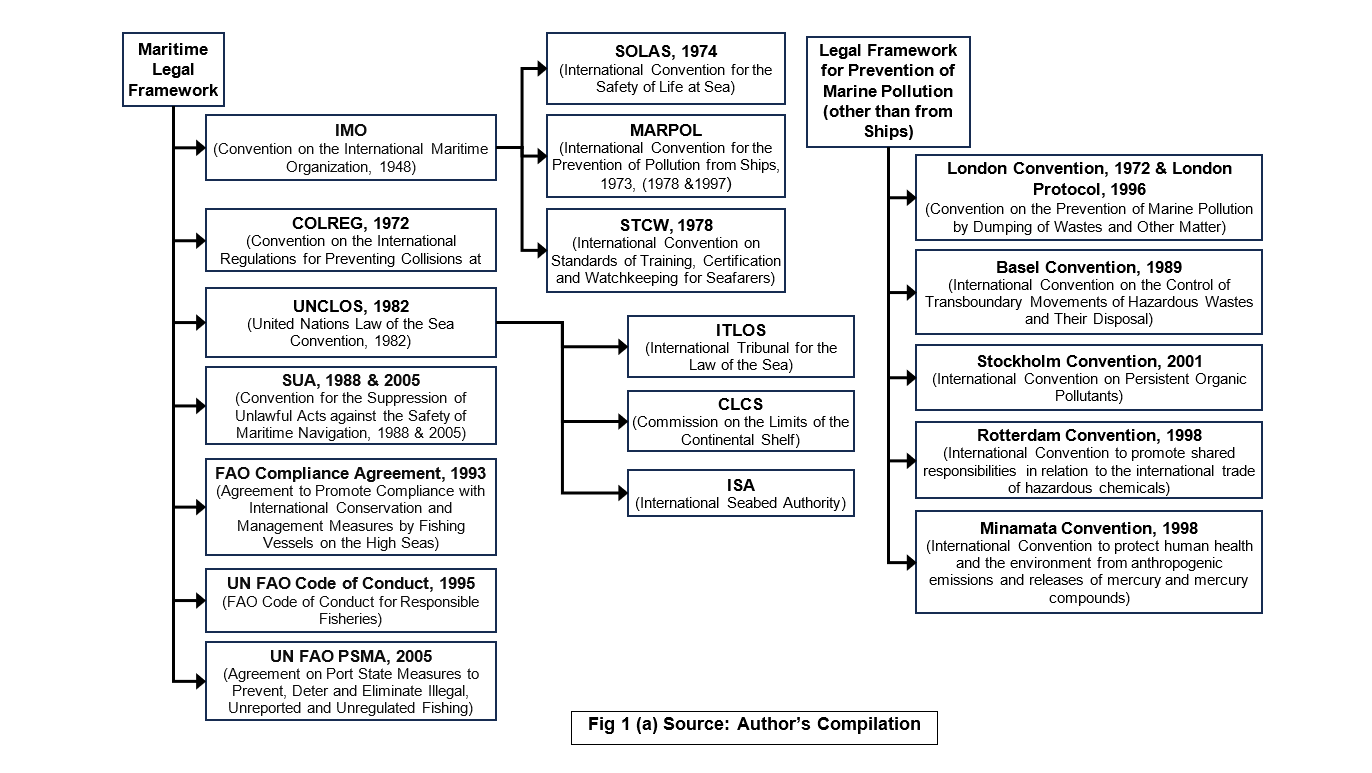

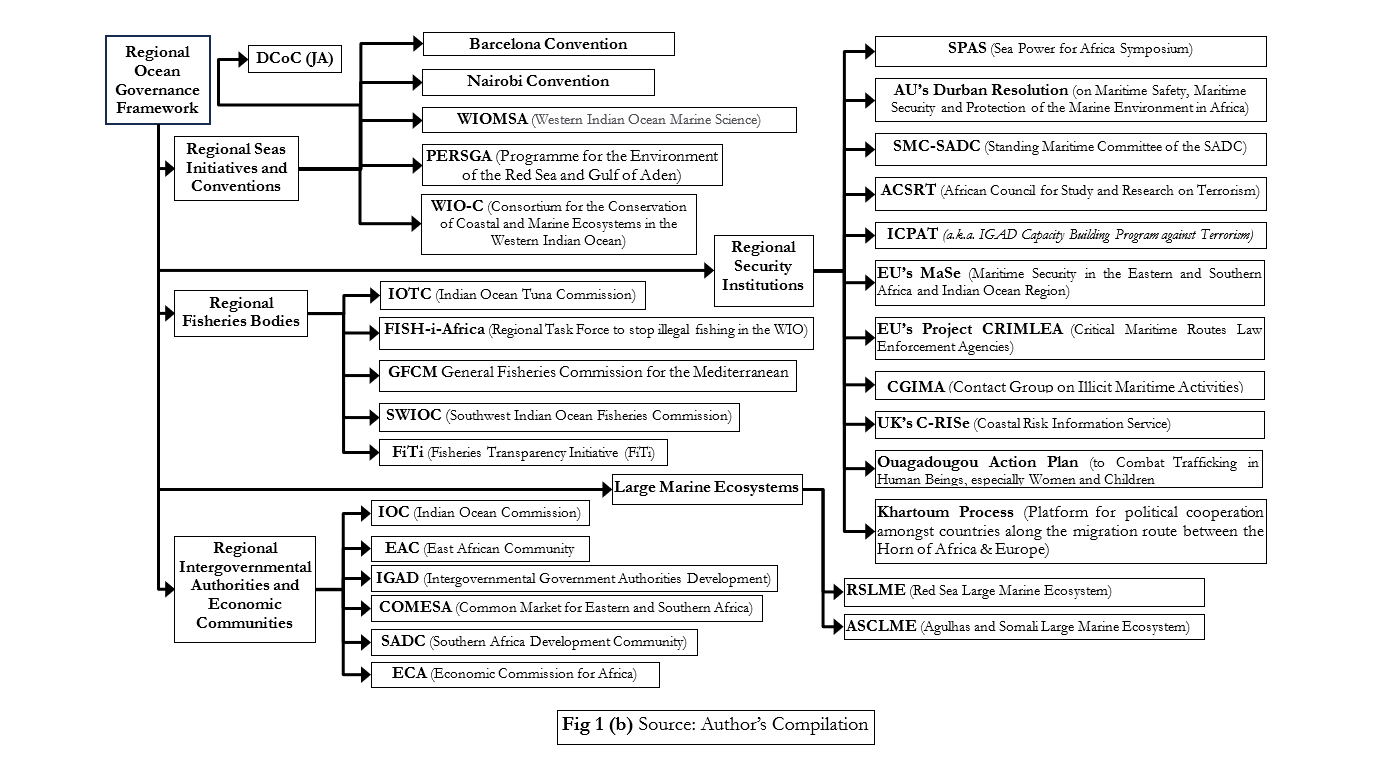

East Africa’s integrated maritime orientation and national policy goals provide space for both resident and the non-resident geopolitical actors. Stability in the region is crucial for the blue-economy development goals of the populace, necessitating the establishment of an overarching security-governance model. Moreover, it is also important to take cognisance of the fact that there are significant differences amongst States of the east African littoral in terms of both, capacity (material wherewithal) as well as capability (human skills and organisational structures that could maximise the effect of whatever capacity does exist). While most navies (though not all) of these States have navies or maritime-security forces that are capable of controlling their respective Territorial Sea, this is seldom true of their EEZs and their Legal Continental Shelves. South Africa was considered to be anchor State in this regard, given that it has the strongest navy in this subregion. However, the State is in a state of societal transformation and South Africa’s navy, like all its other national institutions, is wrestling with the socio-political transition in which the nation currently finds itself. Kenya has a navy that has a reasonable ability to operate within and control its EEZ. However, the maritime forces of other States of the littoral are severely lacking in terms of their capacity and capability to operate meaningfully within and beyond their EEZs.[30] The question that then arises is whether maritime security could in fact be achieved not by relying solely upon the prowess of navies, but rather by synergising the efforts of national and subregional institutions, civilian and/or commercial maritime stakeholders, and civil society as a whole. Could such an amalgam generate the sort of ‘holistic’ maritime security envisaged by the ‘2050 AIMS’? What sets 2050 AIMS apart from other maritime strategies is its emphasis on governance-induced security mechanisms. The strategy urges the utilisation of relevant global and regional legal and institutional structures to build a maritime security-governance mechanism for Africa. Weaving together diverse elements of the strategy, the author has prepared a schematic presenting a coherent global, regional, and sub-regional governmental network of initiatives and partnerships which, taken in aggregate, could yield an effective model of security-governance within the maritime domain of eastern Africa. (Figures 1 (a) and 1 (b) refer)

It is evident from the foregoing figures and the arguments presented in this paper that coastal- and island-States of the eastern African littoral have, indeed, come a long way in developing structures to counter the challenges and maritime threats that they perceive. Unfortunately, the attained capacity and capability, that is, the agency of these States, is not as yet sufficient for them to play a leading role in their own affairs in their coastal waters, their EEZs and their LCS, leave alone challenges that emanate from the high seas themselves.

The Indo-Pacific Oceans’ Initiative (IPOI), whose launch was enunciated by Prime Minister Narendra Modi on November 4, 2019, at the East Asia Summit held in Bangkok, Thailand, holds out enormous promise for all States of the Indo-Pacific, but especially for those States whose shores are lapped by the warm waters of the Indian Ocean. To deliver on this promise that the IPOI holds, India must look as keenly westward towards the shores of East Africa as it does eastward towards those of Southeast Asia and East Asia. There is considerable evidence that the present government in New Delhi is doing just that. It is time for one of more States of the eastern Africa littoral to step up to take a joint lead in one or more of the spokes of the IPOI, leveraging the impressive and entirely commendable structures and legal frameworks that have been put in place.

Now is the time of Africa. Is India ready?

*****

About the Author

Ms Anum Khan is an Associate Fellow at the National Maritime Foundation. Her current research is centred upon the multiple maritime facets of the eastern African littoral, about which she is discernibly passionate. She may be contacted at amgs2.nmf@gmail.com

Acknowledgment

The author would like to express sincere gratitude and appreciation for the invaluable efforts and unwavering guidance provided by Vice Admiral Pradeep Chauhan, AVSM & Bar, VSM (Retd), Director General, NMF. His expertise and assistance played a pivotal role in factually shaping this article and bringing it to its present form.

[1] Kivette, F. N. “MARITIME STRATEGY.” Naval War College Information Service for Officers 4, no. 2 (1951): 27–49. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44794474.

[2] African Union, 2050 Africa’s Integrated Maritime Strategy (AU Version: 1.0), 2012. https://au.int/sites/default/files/documents/30929-doc-2050_aim_strategy_eng_0.pdf.

[3] Ibid, 11.

[4] Africa’s Maritime Domain – Africa’s maritime domain can be understood as anything and everything that is related to sea including ports, coastal infrastructure, shipping, fishing, seaborne trade, offshore energy assets, undersea pipelines and cables, and seabed resources.

[5] David A. Baldwin, “The Concept of Security,” Review of International Studies 23 (1997): 5-26.

[6] Christian Bueger, “What is Maritime Security?” Marine Policy 53 (March 2015): 159-164. DOI:10.1016/j.marpol.2014.12.005.

[7] The ten mentioned maritime threats in 2050 AIM Strategy are Illegal Oil Bunkering/Crude Oil Theft; Money Laundering, Illegal Arms and Drug Trafficking; Environmental Crimes; Piracy and Armed Robbery at Sea, Maritim Terrorism; Human Trafficking, Human Smuggling and Asylum Seekers Travelling by Sea.

[8] Hamad B. Hamad, “Maritime Security Concerns of the East African Community (EAC),” Western Indian Ocean Journal of Marine Science 15, No 2 (2016): 83.

[9] W Andy Knight, “Towards a Subsidiarity Model for Peace making and Preventive Diplomacy: Making Chapter VIII of the UN Charter Operational,” Third World Quarterly 17, No 1 (March 1996): 39.

[10] Extraordinary Session of the Assembly, “African Charter on Maritime Security and Safety and Development in Africa,” African Union (Lome: Togo), October 15, 2016. https://au.int/sites/default/files/treaties/37286-treaty-african_charter_on_maritime_security.pdf.

[11] Economic Commission for Africa (UN), “Africa’s Blue Economy: A Policy Handbook,” (March 2016): 4.

[12] SIDS list given by the United Nations in the Indian Ocean includes Comoros, Mauritius, and Seychelles. https://www.un.org/ohrlls/content/list-sids.

[13] “Ports in Africa, seaports: info, marketplace”. Ports.com. http://ports.com/browse/africa/#/?cf=TZ,MG,KE,MZ,ZA,KM,SO,RE,SC,DJ,MU,YT&df=&tf=&view=list&page=false

[14] Press Information Bureau (GOI), “Text of Prime Minister’s Keynote Address at Shangri La Dialogue,” (June 1, 2018). https://pib.gov.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=179711.

[15] Sanjay J Singh, et al, “Ensuring Secure Seas: Indian Maritime Security Strategy”, New Delhi: Indian Navy, October 2015, https://www.indiannavy.nic.in/sites/default/files/Indian_Maritime_Security_Strategy_Document_25Jan16.pdf.

[16] Africa Centre for Strategic Studies, “Maritime Safety and Security: Crucial for Africa’s Strategic Future”, March 4, 2016. https://africacenter.org/spotlight/maritime-safety-security-crucial-africas-strategic-future/.

[17] Africa Centre for Strategic Studies, “Trends in Africa Maritime Security”, March 15, 2019. https://africacenter.org/spotlight/trends-in-african-maritime-security/

[18] Editorial Team, “Piracy events off East Africa doubled during 2017”, Safety 4 Sea, May 22, 2018. https://safety4sea.com/piracy-events-off-east-africa-doubled-during-2017/.

[19] Press Releases, “Treasury Sanctions Terrorist Weapons Trafficking Network in Eastern Africa”, U.S. Department of the Treasury, November 1, 2022. https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy1066.

[20] Fragile States Index, “Fragile States Index Annual Report 2022” Washington: The Fund for Peace, 2022. https://fragilestatesindex.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/22-FSI-Report-Final.pdf.

[21] The Global Initiative against the Transnational Organised Crime, “The Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing Index”, January 2019. https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/IUU-Fishing-Index-Report-web-version.pdf.

[22] “Story,” Climate Action, “On verge of record drought, East Africa grapples with new climate normal,” UN Environment Programme, March 28, 2022. https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/verge-record-drought-east-africa-grapples-new-climate-normal.

[23] Maoranjan Srivastava, “India’s Food Security and the Maritime-Impacts of Climate Change — The Locust-Intermediaries”, https://maritimeindia.org/indias-food-security-and-the-maritime-impacts-of-climate-change-the-locust-intermediaries/

[24] Ken Booth, Navies and Foreign Policy (New York: Routledge, 2014), 16.

[25] “Country Files> Africa”, France Diplomacy, Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs. https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/en/.

[26] Alison A. Kaufman, “China’s Participation in Anti-Piracy Operations off the Horn of Africa: Drivers and Implications,” Conference Report, CNA, July 2009. https://www.cna.org/reports/2009/D0020834.A1.pdf

[27] “Maritime Security – DCoC”, International Maritime Organisation. https://www.imo.org/en/OurWork/Security/Pages/DCoC.

[28] UNECA, “Global leaders urged to scale up support for the Great Blue Wall initiative”, Africa Renewal: November 2022, https://www.un.org/africarenewal/topic/great-blue-wall-initiative

[29] Pierre Failler et.al, “Africa Blue Economy Strategy Implementation Plan 2021 -2025”, African Union, (December 2020).

[30] Ministry of External Affairs (MEA), “Indo-Pacific Division Briefs,” https://mea.gov.in/Portal/ForeignRelation/Indo_Feb_07_2020.pdf.

Ships Could Bring Invasive Species to Antarctica, Study Warns - EcoWatch

Ships Could Bring Invasive Species to Antarctica, Study Warns - EcoWatch

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!