Abstract

After nearly four decades of acceding to the Antarctic Treaty,[1] the Parliament of India took a significant step on 06 August 2022, by passing the Indian Antarctic Act, 2022.[2] Last year, Dr Jitendra Singh, the Hon’ble Minister of State (Independent Charge) for Earth Sciences, introduced the Bill (No.95 of 2022) in the Parliament,[3] emphasizing its alignment with India’s commitment under the Antarctic Treaty, the Protocol on Environment Protection (Madrid Protocol), and the Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CAMLR).[4] Dr Singh also reiterated India’s dedication in promoting sustainability and protecting the Antarctic environment, whilst also highlighting the importance of creating Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) for preventing IUU fishing.[5] However, despite the sustainability and conservation focus of this national legislation, there are concerns about its actual impact due to the absence of national-level scientific studies identifying the consequences of non-native marine species (NNMS) introduced by Indian-flagged research vessels through biofouling and ballast water exchange.[6] This article aims to assess the potential impact of NNMS on the native biological diversity of Antarctic waters, whilst shedding light on the gaps in India’s role in the conservation of native marine life.

Keywords: ANTARCTIC TREATY, MADRID PROTOCOL, CAMLR, MARINE BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY, BIOFOULING, BIOINVASION

Biological Diversity of Antarctica

The economic exploitation of Antarctica’s marine resources can be traced back to the eighteenth century. However, scientific study of the region’s marine biological resources only gained momentum in the nineteenth and mid-nineteenth century. Expeditions such as those by the HMS Challenger (1872-1876),[7] the SY Belgica (1897-1899),[8] and the RRS Discovery (1901-1904),[9] played a pivotal role in cataloguing the modern taxonomy of these biological resources.[10] The marine biological diversity of Antarctica and its surrounding waters is remarkably varied and exhibits distinct biogeographical patters. Despite the challenging marine environment characterised by cold currents, icebergs, bergy bits, and growlers, the waters surrounding the continent are among the most productive of the world’s oceans.[11] With 44 per cent of species discovered within the Antarctic Specially Protected Areas (ASPAs),[12] recent years have witnessed a significant increase in scientific research focused on understanding species distribution.[13]

If one were to compare the World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS), which is the authoritative classification and catalogue of marine species names,[14] to the Register of Antarctic Species (RAS), it becomes apparent that the latter is specifically focused on capturing the native biological diversity of Antarctica.[15] Narrowing down one’s focus even further to marine species alone, it would be noted that the Register of Antarctic Marine Species (RAMS) has two primary objectives: (1) compiling and managing a comprehensive taxonomic list of species found in the Antarctic marine environment, and (2) establishing a standardised point of reference for marine biodiversity, conservation, and sustainable management.[16] The RAMS is published by the Antarctic Biodiversity Information Facility (ANTA´BIF), which strives to leverage the most advanced technology available to integrate, share, and disseminate all relevant information pertaining to Antarctic biodiversity.[17]

International Legal Instruments for Conservation

The Antarctic Treaty, 1959, which is the overarching legislation governing all activities in Antarctica,[18] has limited scope when it comes to the conservation and preservation of the continent’s living resources.[19] However, the Agreed Measures for the Conservation of Antarctic Fauna and Flora, 1964, enacted under the Treaty, recognises Antarctica as a ‘Special Conservation Area’. This instrument encompasses several important provisions,[20] amongst which are:

- A comprehensive set of rules for wildlife conservation.

- Measures to minimise disruptive impacts on the natural habitats of native birds and mammals.

- Safeguards against pollution of coastal areas.

- Strict prohibitions on the introduction of non-indigenous species, and

- The establishment of information exchange protocols to assess the need for biodiversity protection.

The Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Seals (CCAS), 1972, is a preferred legal instrument designed to foster and accomplish the goals of safeguarding, scientifically studying, and sustainably harvesting Antarctic seals, while maintaining a healthy ecological equilibrium. Recognising the need to prevent a rapid decline in the seal population (due to commercial hunting) through scientific harvesting, the Convention has implemented designated zones where hunting is strictly prohibited.[21] These measures are in place to ensure the long-term preservation and well-being of Antarctic seals, which is a generic term that incorporates the six species of seal (out of the 35 that are to be found worldwide) that live in Antarctica but make up the vast majority of all seals on earth. These six species are Antarctic Fur Seals, Leopard Seals, Ross Seals, Southern Elephant seals, Crabeater Seals and Weddell Seals.[22]

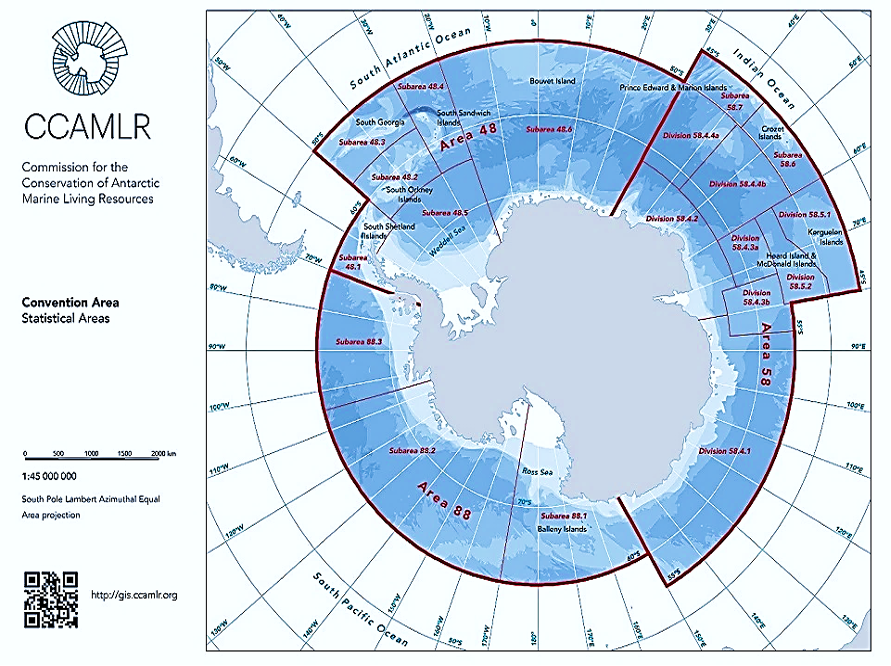

The Convention on Conservation of Marine Living Resources (CAMLR), 1980, represents a collective response to concerns over the increase in unregulated krill-fishing in the waters surrounding Antarctica and its potential detrimental effects on the Antarctic marine ecosystem.[23] The preamble of the Convention acknowledges the concentration of living resources in Antarctica and the growing interest in utilizing these resources as a source of protein. Consequently, it emphasises the importance of conserving marine living resources in Antarctica. To address the issue of illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing in Antarctic waters,[24] the Convention established the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR). The Commission has implemented measures to ensure the sustainable harvesting of target species, particularly the Antarctic toothfish (Although Antarctic fish species are rarely larger than 60 cm, these the Antarctic toothfish can grow in excess of two metres in length and more than 150 kg in mass. While most fish control their buoyancy with a swim bladder, toothfish actually use lipids or fats, adding to their popularity as a food for humans).[25] Amongst the various conservation measures, the Catch Documentation Scheme (CDS) has significantly enhanced the traceability of toothfish harvests from landing sites throughout the trade cycle.[26] Additionally, the Commission has entered into agreements with specific Regional Fisheries Management Organisations (RFMOs) to combat IUU fishing. These RFMOs also share their IUU-vessel lists with the Commission.[27] Further, in accordance with the ‘ecosystem approach’ outlined in Article II of the Convention, the Commission has established the CAMLR Ecosystem Monitoring Program (CEMP). The programme’s objectives include: (1) detecting and recording significant changes in critical components of the marine ecosystem within the Convention area (Fig 1 refers) to serve as a basis for conservation, and (2) distinguish between changes attributed to commercial species harvesting and those caused by environmental variability, encompassing both physical and biological factors.[28]

In order to mitigate the impact of anthropogenic activities on the Antarctic environment, the Protocol on Environment Protection, also known as the Madrid Protocol was established in 1991. The Protocol designates Antarctica as a “natural reserve, devoted to peace and science”, and identifies it as a ‘Special Conservation Area’. The Protocol’s preamble urges nations to collaborate and develop a comprehensive framework for safeguarding the Antarctic environment and its dependent and associated ecosystems, in the best interest of humanity as a whole. To fulfil its commitment to environment protection, the Protocol encompasses several crucial provisions,[29] amongst which the more significant ones are:

- Ban on mining and mineral exploration.

- Prohibition on the introduction of non-native species, and disturbance to the indigenous species.

- Proper waste-management and disposal, and

- Mandatory Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs).

Among the Protocol’s six annexes,[30] Annex V specifically focuses on Area Protection and Management, facilitating the creation of Antarctic Specially Protected Areas (ASPAs). The primary objective of ASPAs is to minimise the impact of anthropogenic activities on Antarctic ecosystems and biodiversity.[31] Additionally, Annex V emphasises that once an ASPA is adopted through consensus among the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Parties, it becomes the collective responsibility of all signatories to ensure the continued protection of the area’s environmental, scientific, historic, aesthetic, or wilderness values.[32]

Fig 1: CAMLR Convention Area

Source: Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources

https://www.ccamlr.org/en/system/files/CCAMLR-Convention-Area-Map.pdf

Antarctica also falls within the category of ‘Special Areas’ defined by the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL), 1973, ensuring the enforcement of the highest environmental protection standards.[33] In alignment with MARPOL’s provisions, the International Maritime Organisation (IMO) introduced the International Code for Ships Operating in Polar Waters, also known as the Polar Code in 2016 to safeguard the Antarctic environment. This comprehensive Code mandates that vessels operating in polar waters must obtain a Polar Ship Certificate, thereby ensuring compliance with stringent regulations.[34] Furthermore, the Polar Code highlights the importance of taking measures to minimise the risk of introducing invasive aquatic species through ships. It emphasises the need for practices such as ballast-water exchange and mitigation of biofouling, which are known pathways for the introduction of invasive marine species.[35] By regulating shipping in polar waters, the Code contributes to the protection and preservation of the unique Antarctic ecosystem.

In contrast to the aforementioned international legal instruments, the Southern Ocean Action Plan, 2021-30 serves as a framework specifically designated to advance the United Nations Agenda 2030 and its diverse array of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), within a polar context. The Plan astutely recognises that human activities such as transportation and infrastructure-development, combined with pollution and the heedless exploitation of living resources, coupled with the rapid acceleration of climate change in high altitudes, are collectively exerting pressure on the environment. By acknowledging these challenges, the Plan seeks to address and mitigate these multifaceted impacts and promotes sustainable practices in the region.[36]

Scientific Collaboration for Conservation

The Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR), a thematic organisation of the International Science Council,[37] has issued a recommendation (SCAR XXIV-3) entitled, “Concerning the Re-introduction of Indigenous Species”. This recommendation asserts that re-introducing indigenous species does not serve any conservation purpose and carries the potential risk of introducing pathogens. Consequently, it urges national committees to actively discourage such practices.[38] Moreover, SCAR conducted the pioneering Antarctic and Southern Ocean Horizon Scan, which examined the impact of invasive species on native Antarctic and Southern Ocean ecosystems.[39]

India in Antarctica

India’s interest in the ‘White Continent’ can be traced back to 1981 when the Indian Antarctic Programme was officially launched, under the guidance of Dr Sayed Zahoor Qasim.[40] The year 1982 marked a significant milestone in that this was when the first team of Indian scientists set foot on Antarctica.[41] This legacy lives on, with the 41st Expedition reaching the continent in 2022.[42] In 1983, the establishment of the Dakshin Gangotri Research Station provided a platform for scientific research and various activities — even though it is no longer functional.[43] Subsequently, in 1988, the Maitri Research Station was established, followed by the Bharati Research Station in 2012.[44] These research stations serve as vital bases for India’s scientific endeavours in the region.

At the international level, India considers Antarctica as a “natural reserve, devoted to peace and science”.[45] On 19 August 1983, India acceded to the Antarctic Treaty and obtained ‘consultative status’ on 12 September of the same year, enabling its participation in the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meetings (ATCMs).[46] Additionally, India became a full member of the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR) on 01 October 1984.[47] In 1986, India joined the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) and the Committee for Environment Protection.[48] In alignment with the CCAMLR, India has actively supported the protection of the Antarctic environment and co-sponsored the EU’s proposal to designate East Antarctica and the Weddell Sea as Marine Protected Areas (MPAs).[49] India also ratified the Madrid Protocol on 14 January 1988, and accepted the Agreed Measures for the Conservation of Antarctic Fauna and Flora on 07 March of the same year.[50] Regarding India’s responsibilities under the Madrid Protocol,[51] during the international conference commemorating the 30th anniversary of its signing,[52] Dr Jitendra Singh, the Hon’ble Minister of Earth Sciences, highlighted India’s adoption of green initiatives, such as wind-energy production and the use of combined heat and power to reduce carbon emissions at the Bharati Station. Dr Singh also acknowledged the troublesome anticipated growth in Antarctic tourism and the deeply disturbing issue of IUU fishing.[53] He emphasised the challenge of climate-induced carbon dioxide uptake by polar oceans, leading to acidification that gradually destroys marine environments and ecosystems, ultimately affecting fisheries and promoting biome shifts. Dr Singh expressed India’s commitment to contributing to the evolving Climate Change Response Work Programme of the Committee for Environment Protection. In 2010, India successfully completed the environmental impact assessment (EIA) initiated in 2006 for the establishment of a new research station at Larsemann Hills, East Antarctica.[54] (This is, today, the Bharati Research Station). This 2006-2010 EIA is emblematic of India’s dedication to responsible and sustainable practices in Antarctica.

At the regional level, India holds membership of the Asian Forum for the Polar Sciences (AFOPS), an NGO founded in 2004. The primary objective of AFOPS is to promote and facilitate collaboration in polar sciences among Asian countries. It serves as a platform for fostering partnerships and advancing scientific research among the Asian countries in the polar regions.[55]

At the national level, the Ministry of Earth Sciences (MoES) has established the National Centre for Polar and Ocean Research (NCPOR), formerly known as the National Centre for Antarctic and Ocean Research (NCAOR). The NCPOR serves as the leading institute for research activities in the polar regions and holds membership in the Council of Managers of the National Antarctic Programme (COMNAP). The COMNAP is dedicated to developing and promoting best practices for managing and supporting scientific research in Antarctica.[56] To safeguard the Antarctic environment, the NCPOR has implemented regulations aimed at preventing the introduction of non-native species. These regulations draw upon the ‘biosecurity guidelines’ jointly issued by the Committee for Environment (CEP) and COMNAP, as well as the ‘Guidelines for Boat, Clothing, and Equipment Decontamination’ provided by the International Association of Antarctic Tour Operators (IAATO).[57] By adhering to these guidelines, the NCPOR ensures that appropriate measures are taken to maintain the pristine nature of the Antarctic ecosystem.

Similarly, the MoES has established the Centre for Marine Living Resources and Ecology (CMLRE),[58] which serves as the central institute responsible for organising, coordinating and promoting ocean-development activities. These encompass a variety of activities such as mapping living resources, creating an inventory of commercial exploitable marine life, ensuring optimal utilisation through ecosystem management, and conducting research and development in the field of marine living resources and ecology.[59] Since 2011, the CMLRE has undergone a transformative process, evolving into a regional Ocean Biodiversity Information System (OBIS) known as the Indian Ocean Biodiversity Information System (IndOBIS). It actively contributes to the extensive OBIS database, enriching global understanding of the biodiversity found in the Indian Ocean. Through its participation, the CMLRE plays a crucial role in enhancing knowledge and awareness of the diverse marine ecosystems in the region.[60]

National Legal Framework

The Indian Antarctic Act, 2022, aims to provide national measures that would protect the Antarctic environment and its dependent and associated ecosystems, thereby giving effect to the Antarctic Treaty, the Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources, and the Madrid Protocol.[61] As per this law , the term ‘Antarctic Environment’ incorporates the ecosystems dependent-on and associated-with the Antarctic environment, the intrinsic value of its wilderness and aesthetics, and its values as an area for the conduct of scientific research or research that is essential to understand the global environment, the climate and the composition of the atmosphere.[62] The law further defines terms including ‘native bird’, ‘native invertebrate’, ‘native mammal’, ‘native plant’, and ‘specially protected species’.[63] To preserve and conserve the environmental and wilderness value of Antarctica, the law specifies that, without proper authorisation or permit:

- No person shall engage in activity that results in the significant change of the habitat of any specially protected species or population of any native biodiversity.[64]

- No person, or vessel or aircraft shall introduce any animal or species that is not indigenous to Antarctica.[65]

- No person shall introduce into any part of Antarctica any microscopic organism of a species which is not indigenous.[66]

- No person, or vessel or aircraft shall enter any Antarctic Specially Protected Area or a marine protected area.[67]

- No vessel shall, while in Antarctica, discharge into the sea any oil or oily mixture, effluent, bilge water or any food waste.[68]

- No person shall undertake commercial fishing in Antarctic waters without permit from the Secretariat of the CCAMLR.[69]

- No vessel shall, while in Antarctica, discharge into the sea any garbage, plastic or other product or substance that is harmful to the marine environment.[70]

Threats to Antarctic Marine Biological DiversityFor centuries, Antarctica has been revered for its pristine marine environment, which fostered flourishing biological diversity in the surrounding waters. However, the dynamics have shifted over time, and with the rise of anthropogenic activities on the continent, new threats have emerged:

- Reverse Zoonosis Transmission of Diseases: The term ‘reverse zoonosis’ pertains to the transmission of infections or diseases from humans to animals in natural conditions.[71] Until mid-March 2020, Antarctica was widely regarded as the only continent free from SARS-CoV-2. However, this changed when 128 out of 217 passengers aboard a cruise ship visiting the continent tested positive for the virus and were isolated in the open ocean.[72] This incident raised concerns about the potential introduction of the virus to the native biological diversity.[73] In response, a preliminary study was conducted to assess the impact of reverse zoonosis transmission of diseases.[74] The study revealed that –

- The environmental conditions in Antarctica favour the SARS-CoV-2 virus, and that cetaceans are more vulnerable than avian fauna.[75]

- Tourists and wildlife researchers/scientists could be the possible carriers of the virus.[76]

- Wildlife migration could also be a means of spreading the virus throughout the migratory route.

- No proper study or information is available regarding the presence of deadly viruses in Antarctic biological diversity.[77]

- Marine Bioinvasion. The term ‘bioinvasion’ refers to the introduction of alien species into an environment, which can lead to extensive destruction by rapidly colonising an area or displacing native species.[78] Extensive hull studies conducted by various international authorities have revealed that bioinvasion is a significant problem in Antarctic waters.[79] A specific study identified the presence of four non-native species and one cryptogenic species in Antarctic waters, along with six species in the pathways to the continent that have the potential to become invasive. Additionally, research suggests that rising water temperatures,[80] decreasing ice cover,[81] and ocean acidification may create favourable conditions for non-native species to thrive in Antarctic waters.[82] With over 500 voyages occurring annually to Antarctica, bioinvasion poses a serious threat. Moreover, the violation of international biofouling guidelines and ballast water norms by numerous IUU vessels could further contribute to the introduction of non-native marine species. The ship-routes that lead to Antarctica and the duration spent in ports enroute also play a role in determining the types of non-native species being transported, whether on the hull or in the ballast water tanks.[83]

- Marine Environment Pollution. The presence of microplastics in the Weddell Sea, a marine protected area, poses a significant threat to marine biodiversity.[84] Shipping activities are considered as the primary source of microplastic pollution in Antarctic waters. Additionally, the contamination of Antarctica’s shoreline with heavy metals could also jeopardise the marine environment and its biological diversity.[85]

- Threats to Marine Living Resources. The marine biological diversity of Antarctica and its surrounding waters faces significant threats from IUU fishing,[86] overfishing,[87] as well as poaching activities.[88] These destructive practices not only deplete the ocean’s resources but also disrupt the delicate ecological balance.

India’s Antarctic-Conservation Challenges

Even though India has maintained a presence in Antarctica since 1983, it was not until last year (2022) that the Indian Parliament passed a national law for protection of the Antarctic environment and its biological diversity. Until the passage of the Indian Antarctic Act of 2022, India had no national policy to regulate activities on the continent, giving rise to certain challenges:

- Omission of Marine Environment Impact Studies. Data derived from numerous environmental impact assessments reveals the presence of environmental pollutants around Indian research stations, and heavy-metal pollution along the shoreline of Antarctica.[89] There is a high chance of these pollutants entering the marine environment, either by anthropogenic activities, or by natural means, thereby threatening Antarctica’s marine biological diversity. Article 3(2)(b) of the Madrid Protocol specifies that activities in the Antarctic Treaty area shall be planned and conducted so as to avoid (i) significant changes in the atmospheric, terrestrial (including aquatic), glacial or marine environments, (ii) detrimental changes in the distribution, abundance or productivity of species or populations of fauna and flora, (iii) endangerment of such species or populations of such species already threatened, and (iv) degradation of the areas with biological and wilderness significance.[90] Annex I of the Protocol also specifies that if an activity is likely to have more than a minor or transitory impact, a Comprehensive Environmental Evaluation shall be prepared, and such evaluation should (i) consider the possible indirect or second order impacts of the proposed activity, and (ii) consider the cumulative impacts of the proposed activity in light of existing activities and other known planned activities.[91] Article 5 of Annex I further stipulates that procedures shall be put in place, including the appropriate monitoring of key environmental indicators, so as to assess and verify the impact of any activity.[92] Article 4 of Annex V states that in order to minimise environmental impacts in any area, including any marine area, where activities are being conducted or may be conducted, such an area could be designated as an Antarctic Specially Protected Area.[93] The lack of any national level environmental impact studies for the Antarctic marine environment identifying the impact of environmental pollutants and heavy metal pollution on the native biological diversity, and the omission of such studies by the relevant authorities, is ultra vires the Madrid Protocol and its annexures.

- Omission of Research on Bioinvasion. Biofouling and ballast-water exchange are widely considered as major sources of bio-invasion of the marine environment. These non-native marine species, often referred to as ‘invasive species’, could disrupt the entire Antarctic marine environment and threaten native biological diversity. At the international level, the application of the ‘Intercontinental Checklists’, prepared by the SCAR and COMNAP in 2019, is limited to biofouling of rigid-hull inflatable-collar craft (such as Zodiacs), barges, ship-tenders, and other small watercraft.[94] In India, there are no scientific studies identifying (i) the native species already thriving in the Antarctic marine environment, (ii) the possibility of such native species becoming ‘invasive’, and (ii) the impact of such invasive species on the native biological diversity. These omissions by the relevant authorities are, likewise, ultra vires the provisions of the Polar Code and the Annex II of the Madrid Protocol,[95] and violate the essence of environment protection envisaged in the Antarctic Treaty.

Policy Recommendations

To address the above-mentioned challenges and abide by the provisions of the Indian Antarctic Act, 2022, which now regulates all activities in the continent, it is important that the Ministry of Earth Sciences consider the following recommendations for conservation of the native marine biological diversity in Antarctica:

- Ministry of Earth Sciences. The Ministry must formulate a national level comprehensive ‘Antarctic Policy’, factoring India’s interests in the continent, designed to improve national and regional cooperation necessary to protect the Antarctic environment.

- National Centre for Polar and Ocean Research (NCPOR). The NCPOR must collaborate with shipbuilding companies to ensure that the latter incorporate various aspects of ‘green shipping’ in their ocean-going research vessels, including the prevention of bioinvasion through the application of ‘green norms’ in shipbuilding and ship-repair practices, while also analysing sustainable trends in respect of underwater-hull protection practices and the production of ballast-free vessels.

- National Institute of Ocean Technology (NIOT). The NIOT must expeditiously:

- Undertake ‘hull studies’ of Indian-flagged research vessels, so as to identify the impact of biofouling and bio-invasion.

- Undertake scientific studies to identify the impact of ballast-water exchange in consideration of its high potential of introducing non-native marine species into Antarctic waters.

- Formulate national policies derived from the IMO Resolution MEPC.207 (62), Annex 26 – “Guidelines for the Control and Management of Ships Biofouling to Minimise the Transfer of Invasive Aquatic Species”, adopted on 15 July 2011.

- Centre for Marine Living Resources and Ecology (CMLRE). The CMLRE must undertake research studies to identify native species that have already been introduced into the Antarctic marine environment and in the pathways to the continent, which have the potential of becoming ‘invasive’, and the impact of such species on the marine biological diversity native to Antarctica.

The Way Forward

Although the Indian Parliament has acted commendably in passing a national law to regulate activities in Antarctica, it is almost certain that the authorities remain largely unaware of the impact of bioinvasion on the native marine biological diversity of the continent. There is, therefore, an urgent need to fill this gap in order to conserve and protect the Antarctic environment and to maintain the ecological balance. Having played a key role in the formulation of the Southern Ocean Action Plan,[96] (even though India — like the International Hydrographic Organisation [IHO] itself does not as yet officially recognise the ‘Southern Ocean’) undertaking conservation measures would help India achieve the targets of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 14 in a polar context. To prevent wildlife crimes, inclusive of IUU fishing and poaching of marine life in Antarctic waters, India should join hands with the regional organisations working towards that end. The nodal agencies should approach the National Maritime Foundation (NMF), India’s foremost maritime think-tank for further research in this domain to overcome the challenges.

To ensure that India is working towards creating a ‘Sustainable Antarctic Environment’ it is imperative that the MoES and the NMF collaborate to formulate and a comprehensive ‘Antarctic Policy’.

*****

About the Author

John J Vachaparambil is an Associate Fellow at the National Maritime Foundation and meaningfully contributes to the Foundation’s ‘Public International Maritime Law’ (PIML) Cluster. His current research focuses on the legal aspects of IUU fishing, and the conservation of the marine biological diversity beyond areas of national jurisdiction (BBNJ). He may be contacted at law5.nmf@gmail.com.

Acknowledgement

The author wishes to acknowledge the valuable suggestions provided by Ms Ayushi Srivastava, Research Associate, Multi-Disciplinary Technical Cluster (MDTC), NMF.

[1] Secretariat of the Antarctic Treaty, “Parties”, https://www.ats.aq/devAS/Parties?lang=e.

[2] Ministry of Law and Justice, “The Indian Antarctic Act, 2022”, 06 August 2022, The Gazette of India, https://prsindia.org/files/bills_acts/acts_parliament/2022/The%20Indian%20Antarctic%20Act,%202022.pdf.

[3] The Indian Antarctic Bill 2022, Bill No. 95 of 2022, http://164.100.47.4/BillsTexts/LSBillTexts/Asintroduced/95_2022_LS_ENG.pdf.

[4] Ministry of Earth Sciences, “Parliament passes the Indian Antarctic Bill, 2022 aimed at having India’s own national measures for protecting the Antarctic environment and dependent and associated ecosystem”, 01 August 2022, Public Information Bureau, https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1847047.

[5] Ministry of Earth Sciences, “India extends support for protecting the Antarctic environment and for designating East Antarctica and the Weddell Sea as Marine Protected Areas”, 30 September 2021, Public Information Bureau, https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1759694.

[6] D Rajasekhar, et.al “Indian Research Ships Features and Future”, August 2014, https://nopr.niscpr.res.in/bitstream/123456789/29276/1/SR%2051(8)%2032-37.pdf.

[7] The Challenger Expedition (1872-76), https://antarcticguide.com/about-antarctica/antarctic-history/early-explorers/14the-challenger-expedition-1872-76/#:~:text=On%2016%20February%201874%2C%20Challenger,Circle%2C%20was%20conducted%20under%20sail.

[8] The Voyage of the Belgica to the Antarctic (1897-1899), https://www.discoveringbelgium.com/voyage-of-the-belgica/.

Also see: Adrien de Gerlache – Belgica Belgian Antarctic Expedition 1897-1899, https://www.coolantarctica.com/Antarctica%20fact%20file/History/antarctic_whos_who_belgica.php.

[9] Dundee Heritage Trust, “The Story of RRS Discovery”, https://www.rrsdiscovery.co.uk/exploration-article/the-story/.

[10] Huw J Griffiths, “Antarctic Marine Biodiversity – What Do We Know About the Distribution of Life in the Southern Ocean?”, 2010, PLoS ONE, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0011683.

[11] Antarctic Marine Life and Adaptations, https://www.coolantarctica.com/Antarctica%20fact%20file/wildlife/antarctic_animal_adaptations2.php.

[12] The National Centre for Polar and Ocean Research, “Antarctica Specially Protected Areas”, https://ncpor.res.in/antarcticas/display/412-antarctica-specially-protected-area.

[13] Hannah S Wauchope, et.al “A Snapshot of biodiversity protection”, 2019, https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-019-08915-6.

[14] World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS), https://marinespecies.org/.

[15] The Register of Antarctic Species (RAS), https://ras.biodiversity.aq/.

[16] The Register of Antarctic Marine Species (RAMS), https://www.marinespecies.org/rams/.

Also see: The Register of Antarctic Marine Species, “Metadata Dataset”, https://www.gbif.org/dataset/e9c227e0-adea-4530-8b2c-e16b06553b6d#description.

[17] Anton P Van De Putte, et.al “The Antarctic Biodiversity Information Facility (ANTA´BIF) Final Report – SD/BA/856”, Science for a Sustainable Development (SSD), https://orfeo.belnet.be/bitstream/handle/internal/4239/AntaBIF_FinRep.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

[18] Secretariat of the Antarctic Treaty, “The Antarctic Treaty”, https://www.ats.aq/e/antarctictreaty.html.

[19] Article IX 1(f) of the Antarctic Treaty, https://documents.ats.aq/keydocs/vol_1/vol1_2_AT_Antarctic_Treaty_e.pdf.

[20] Agreed Measures for the Conservation of Antarctic Fauna and Flora, https://www.ecolex.org/details/treaty/agreed-measures-for-the-conservation-of-antarctic-fauna-and-flora-tre-000079/.

[21] Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Seals (CCAS), https://atcm44-berlin.de/en/0_atcm-xliv-english/1-the-antarctic-treaty-consultative-meetings/1_2-a-success-story-of-international-cooperation/1_2_3-ccas/.

[22] Antarctica Seals: Pictures, Facts and Information, https://www.antarcticaguide.com/antarctica-wildlife-2/antarctica-seals.

[23] Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR), “CAMLR Convention”, https://www.ccamlr.org/en/organisation/camlr-convention.

[24] IUU Fishing was prevalent in Antarctica from the 1990s and it is estimated to be six times the catch reported by the authorised fishing vessels.

[25] The Last Ocean, http://www.lastocean.org/commercial-fishing/about-toothfish/all-about-antarctic-toothfish-__I.2445

[26] Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR), “Catch Documentation Scheme (CDS)”, https://www.ccamlr.org/en/compliance/catch-documentation-scheme.

[27] CCAMLR Conservation Measures, “Measures and Resolutions”, https://cm.ccamlr.org/.

Also see: South Pacific Regional Fisheries Management Organisation (SPRFMO), “SPRFMO IUU LIST”, http://www.sprfmo.int/measures/iuu-lists/.

Also see: South East Atlantic Fisheries Organisation (SEAFO), “IUU”, http://www.seafo.org/Management/IUU.

Also see: Southern Indian Ocean Fisheries Agreement (SIOFA), “IUU vessels”, http://www.apsoi.org/mcs/iuu-vessels.

[28] CCAMLR Ecosystem Monitoring Program (CEMP), https://www.ccamlr.org/en/science/ccamlr-ecosystem-monitoring-program-cemp.

Also see: IUCN Red List, “Countries and Regions used in the Red List”, https://www.iucnredlist.org/resources/country-codes#Antarctica.

[29] Ibid.13, Hannah S Wauchope, et.al “A Snapshot of biodiversity protection”.

[30] National Centre for Polar and Ocean Research, “Madrid Protocol”, https://ncpor.res.in/antarcticas/display/411-madrid-protocol#:~:text=The%20Protocol%20on%20Environmental%20Protection,2.

[31] Annex V to the Madrid Protocol, 1991, “Area Protection and Management”, https://ncpor.res.in/files/Antarctic_treaty/ANNEX%20V.pdf.

[32] Ibid.13, Hannah S Wauchope, et.al “A Snapshot of biodiversity protection”.

[33] International Maritime Organisation, “Special Areas under MARPOL”, https://www.imo.org/en/OurWork/Environment/Pages/Special-Areas-Marpol.aspx.

[34] International Maritime Organisation, “Shipping in Polar Waters”, https://www.imo.org/en/MediaCentre/HotTopics/Pages/polar-default.aspx.

[35] How the Polar Code Protects the Environment, https://wwwcdn.imo.org/localresources/en/MediaCentre/HotTopics/Documents/How%20the%20Polar%20Code%20protects%20the%20environment%20(English%20infographic).pdf.

[36] Janssen AR, et.al “Southern Ocean Action Plan (2021-30) in support of the United Nations Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development”, 2022, https://zenodo.org/record/6412191#.Y1IelvxBzrc.

[37] The Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research, https://www.scar.org/.

[38] Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR), “Recommendation SCAR XXIV-3 Concerning the Re-introduction of Indigenous Species”, https://scar.org/library/policy/codes-of-conduct/3410-recommendation-scar-re-introduction-of-indigenous-species/.

[39] Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR), “The 1st SCAR Antarctic and Southern Ocean Science Horizon Scan – Final List of Questions”, https://www.scar.org/scar-library/other-publications/horizon-scan/3348-hs-final-list-of-questions/file/.

[40] Ministry of Earth Sciences, “India launches the 41st Scientific Expedition to Antarctica”, 15 November 2021, Public Information Bureau, https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1771934#:~:text=The%20Indian%20Antarctic%20program%2C%20which,and%20Bharati%20are%20fully%20operational.

Also see: Ministry of Science and Technology, Department of Biotechnology, “Syed Zahoor Qasim”, http://nobelprizeseries.in/tbis/sz-qasim.

[41] National Centre for Polar and Ocean Research (NCPOR), “India in Antarctica”, https://ncpor.res.in/antarcticas/display/166-india-in-antarctica.

[42] Ibid.40, Ministry of Earth Sciences, “India launches the 41st Scientific Expedition to Antarctica”.

[43] Ibid.41, National Centre for Polar and Ocean Research (NCPOR), “India in Antarctica”.

[44] NCPOR, “India Antarctic Station Catalogue”, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/61073506e9b0073c7eaaf464/t/61562e98a0d93440eb86ef17/1633037978604/India_Antarctic_Station_Catalogue_Aug2017.pdf.

[45] Ministry of Science and Technology, “Union Minister Dr Jitendra Singh says, India is committed to curtail carbon emissions in the Antarctic atmosphere”, 04 October 2021, Public Information Bureau, https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1760870#:~:text=With%20Himadri%20station%20in%20Ny,entered%20into%20force%20in%201998.

[46] Ibid.1, Secretariat of the Antarctic Treaty, “Parties”.

[47] Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR), “Overview of SCAR Members”, https://www.scar.org/about-us/members/overview/#:~:text=Union%20members%20are%20International%20Astronomical,Geological%20Sciences%20(IUGS)%2C%20International.

[48] Centre for Marine Living Resources and Ecology (CMLRE), “International Collaborations”, https://www.cmlre.gov.in/collaborations/international.

[49] Ibid.5, Ministry of Earth Sciences, “India extends support for protecting the Antarctic environment and for designating East Antarctica and the Weddell Sea as Marine Protected Areas”.

[50] Protocol on Environment Protection to the Antarctic Treaty, https://treaties.un.org/Pages/showDetails.aspx?objid=080000028006ab63&clang=_en.

[51] Ibid.20, Agreed Measures for the Conservation of Antarctic Fauna and Flora.

[52] Commemoration of the 30th Anniversary of the Madrid Protocol, “Antarctica, Present and Future”, 04 October 2021, https://www.miteco.gob.es/es/biodiversidad/formacion/informefinal_protocolodemadrid_ingles_tcm30-533003.pdf.

[53] Ibid.45, Ministry of Science and Technology, “Union Minister Dr Jitendra Singh says, India is committed to curtail carbon emissions in the Antarctic atmosphere”.

[54] Environmental Impact Assessments in Antarctica, Earthstar Geographics, https://antarctictreaty.maps.arcgis.com/apps/webappviewer/index.html?id=967e09935fae4cb891bcc193a2957357.

Also see: Ministry of Earth Sciences, Government of India, “New Research Centre in Antarctica”, 03 March 2010, https://www.moes.gov.in/sites/default/files/LU924_4_15_2010.pdf.

Also see: Secretariat of the Antarctic Treaty, “Draft Comprehensive Environmental Evaluation (CEE) of New Indian Research base at Larsemann Hills, East Antarctica”, https://www.ats.aq/devAS/EP/EIAItemDetail/954.

[55] Asian Forum for Polar Sciences, “About AFOPS”, https://afops.org/home/about#A.

[56] Council of Managers of the National Antarctic Programme (COMNAP), “Our Members”, https://www.comnap.aq/our-members.

[57] The National Centre for Polar and Ocean Research (NCPOR), “Non-Native Species”, Non-Native Species: Non-Native Species (ncpor.res.in).

[58] Centre for Marine Living Resources and Ecology (CMLRE), https://www.cmlre.gov.in/#.

[59] Centre for Marine Living Resources and Ecology (CMLRE), “About CMLRE”, https://www.cmlre.gov.in/about-us/about-cmlre.

[60] Ibid.48, Centre for Marine Living Resources and Ecology (CMLRE), “International Collaborations”.

Also see: IOC-UNESCO “International Oceanographic Data and Information Exchange (IODE)”, https://www.iode.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=373&Itemid=100089.

[61] Ibid.2, Ministry of Law and Justice, “The Indian Antarctic Act, 2022”.

[62] §3(1)(f), The Indian Antarctic Act, 2022.

[63] §8, The Indian Antarctic Act, 2022.

[64] §8(g), The Indian Antarctic Act, 2022.

[65] §9, The Indian Antarctic Act, 2022.

[66] §10, The Indian Antarctic Act, 2022.

[67] §11, The Indian Antarctic Act, 2022.

[68] §13, The Indian Antarctic Act, 2022.

[69] §16, The Indian Antarctic Act, 2022.

[70] §22, The Indian Antarctic Act, 2022.

Also see: The term ‘garbage’ in respect of a vessel means all kinds of victual, domestic and operational waster, generated during the normal operation of the ship and has to be disposed of continuously or periodically.

Also see: The term ‘waste’ means unusable unserviceable movable property, including solid, liquid, and gaseous matter, which the possessor or generator wants to discharge, or the controlled disposal of which is called for.

[71] Merriam Webster, “reverse zoonosis”, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/reverse%20zoonosis.

[72] Alvin J Ing, et al “COVID-19: in the footsteps of Ernest Shackleton”, 27 May 2020, Thorax, http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-215091.

[73] Alexander J Keeley, et al “Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection: the tip or the iceberg?”, 24 June 2020, Thorax, http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-215337.

[74] Andrés Barbosa, et al “Risk assessment of SARS-CoV-2 in Antarctic wildlife”, 10 February 2021, Science of the Total Environment, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.143352.

[75] H. Schütze, “Coronaviruses in Aquatic Organisms”, 09 September 2016, Aquaculture Virology, Chapter 20, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-801573-5.00020-6.

[76] Joana Damas, et al “Broad host range of SARS-CoV-2 predicted by comparative and structural analysis of ACE2 in vertebrates”, 21 August 2020, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2010146117.

[77] Ibid.74, Andrés Barbosa, et al “Risk assessment of SARS-CoV-2 in Antarctic wildlife”.

[78] Dr Chetan A Gaonkar, “Marine Bio-invasion”, 11 February 2017, TERI, https://www.teriin.org/opinion/marine-bioinvasion#:~:text=Introduction%20of%20an%20alien%20species,or%20by%20eliminating%20native%20species.

[79] Ibid.74, Andrés Barbosa, et al “Risk assessment of SARS-CoV-2 in Antarctic wildlife”.

[80] Arlie H McCarthy, “Antarctica’s unique ecosystem is threatened by invasive species ‘hitchhiking’ on ships’, 11 January 2022, The Conservation, https://theconversation.com/antarcticas-unique-ecosystem-is-threatened-by-invasive-species-hitchhiking-on-ships-174640.

Also see: Yves Frenot, et.al “Biological invasions in the Antarctica: extent, impacts and implications”, 11 June 2004, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1017/S1464793104006542.

[81] Peter Convey & Tom Hart, “Polar invasion: how plants and animals would colonise an ice-free Antarctica”, 15 September 2015, https://theconversation.com/polar-invasion-how-plants-and-animals-would-colonise-an-ice-free-antarctica-47369.

[82] Arlie H McCarthy, “The final frontier for marine biological invasions”, 13 February 2019, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/gcb.14600.

Also see: British Antarctic Survey, “Changing Biodiversity”, 01 July 2012, https://www.bas.ac.uk/project/changing-biodiversity/.

Also see: Kathryn Smith, “The march of the king crabs: a warning from Antarctica”, 20 July 2015, https://theconversation.com/the-march-of-the-king-crabs-a-warning-from-antarctica-43062.

[83] Arlie H McCarthy, et.al “Ship traffic connects Antarctica’s fragile coasts to worldwide ecosystems”, 01 November 2021, https://www.pnas.org/doi/epdf/10.1073/pnas.2110303118.

[84] Clara Leistenschneider, et.al “Microplastics in the Weddell Sea (Antarctica): A Forensic Approach for Discrimination between Environmental and Vessel-Induced Microplastics”, 29 November 2021, https://pubs.acs.org/doi/pdf/10.1021/acs.est.1c05207.

[85] Wan-Loy Chu, et.al “heavy metal pollution in Antarctica and its potential impacts on algae”, June 2019, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polar.2018.10.004.

[86] Mary Lack, “Continuing CCAMLR’s Fight Against IUU Fishing for Toothfish”, 2008, WWF Australia and TRAFFIC, https://www.traffic.org/site/assets/files/5463/traffic_species_fish31.pdf.

Also see: IUU Fishing of the Patagonian Toothfish in the Southern Ocean, The Fish Project, http://thefishproject.weebly.com/iuu-fishing-of-the-patagonian-toothfish.html.

[87] Richa Syal, “License to Krill: The destructive demand for a better fish oil”, 07 September 2021, The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/sep/07/license-to-krill-the-destructive-demand-for-a-better-fish-oil.

[88] Remarkable Numbers of Antarctic Blue Whales Sighted in South Georgia, WWF, https://www.wwf.org.uk/success-stories/antarctic-blue-whales.

Also see: Human Impacts on Antarctica and Threats to the Environment – Whaling and Sealing, Cool Antarctica, https://www.coolantarctica.com/Antarctica%20fact%20file/science/threats_sealing_whaling.php.

[89] Ibid.54, Secretariat of the Antarctic Treaty, “Draft Comprehensive Environmental Evaluation (CEE) of New Indian Research base at Larsemann Hills, East Antarctica”.

[90] Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty, https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwjz94_pxKP-AhUVh1YBHQ7RB04QFnoECBcQAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fdocuments.ats.aq%2Frecatt%2Fatt006_e.pdf&usg=AOvVaw38MFwPhWexC6Ug0fHdh5i2.

[91] Article 3, Annex I to the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty, “Environmental Impact Assessment”, https://ncpor.res.in/files/Antarctic_treaty/ANNEX%20I.pdf.

[92] Ibid.91, Annex I to the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty.

[93] Ibid.31, Annex V to the Madrid Protocol, 1991.

[94] Checklist for supply chain managers of National Antarctic Programmes for the reduction in risk of transfer of non-native species, https://ncpor.res.in/files/non%20native%20species/COMNAP-SCAR_Checklist%20for%20Supply%20Managers%20%20Poster.pdf.

Also see: Inter-continental Checklists for supply chain managers of the National Antarctic Programmes for the reduction in risk of transfer of non-native species, May 2019, https://ncpor.res.in/files/non%20native%20species/SCAR-COMNAP-Inter-continental%20Checklist%20for%20Supply%20Managers.pdf.

[95] Article 4, Annex 4 to the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty, “Introduction of Non-Native Species and Diseases”, https://ncpor.res.in/files/Antarctic_treaty/ANNEX%20II.pdf.

[96] Ibid.53, Asian Forum for Polar Sciences, “About AFOPS”.

Ships Could Bring Invasive Species to Antarctica, Study Warns - EcoWatch

Ships Could Bring Invasive Species to Antarctica, Study Warns - EcoWatch

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!