Japan’s 25th Defence Minister, Mr Kihara Minoru, released the latest edition of the nation’s Defence White Paper, “Defence of Japan 2024”, marking the 50th issue since the first edition was published, in 1970.[1] This milestone coincides with the 70th anniversary of the establishment of the Ministry of Defence (MOD) and the Self-Defence Forces (SDF), which was founded on 01 July 1954. It is important to note that only a brief summary of the document, in the form of a ‘digest’, is currently available to the public. This will hereinafter be referred to as the ‘DOJ-24 Digest’.[2]

Historically, annual editions of Japan’s Defence White Papers have provided vital insights into the nation’s defence posture and evolving strategic priorities in consonance with the changing geopolitical environment. This document initially provides an overview of the challenges facing the international community, and significantly, notes that many States do not share universal values or political and economic systems. The inevitable interaction between such States with opposing worldviews, contrasting governance systems and differing international relations outlooks — which cannot be avoided because of the dynamics of an increasingly globalised environment — often presents grounds for increased global instability. The 2024 edition also emphasises the development of Integrated Air and Missile Defence (IAMD) as a critical component of Japan’s strategy to protect itself from missile threats, particularly from North Korea and China. Additionally, it addresses growing threats in cyberspace and other domains, alongside emerging global security issues, such as information warfare and climate change.

The major highlights concerning Japan’s national security, as discerned from the “DOJ-24 Digest”, have been analysed under the following heads:

- China as an adversary of Japan

- Japan’s Self-Defence Capability Assessment

- Threat-mitigating strategies, including collaboration with the US and like-minded countries

China as an adversary of Japan

The Japanese Defence Minister expressed particular concern over China’s growing missile capabilities, noting that Beijing was developing new-generation offensive weapons, including shore-launched anti-ship missiles with a range of 1,000 km, and hypersonic missiles with a range of 500 km. He specifically flagged the ongoing Chinese activities of establishing military bases to consolidate its territorial claims, and challenging international maritime laws, as “efforts to create a fait accompli” situation.[3]

In the same vein, the “DOJ-24 Digest” elaborates upon China’s growing military activities, particularly around the Senkaku Islands, the Sea of Japan, and the western Pacific Ocean. China’s extension of its influence beyond the First Island Chain, to the Second Island Chain, which includes Japan’s Ogasawara Islands (near Okinawa) and Guam, is also highlighted as a major concern.[4] The persistent militarisation by China and its hardline postures are noted as serious concerns for Japan, especially in ‘grey zone’ situations involving territorial disputes, particularly around the Senkaku Islands and the South China Sea.

The “DOJ-24 Digest” also accords considerable attention to Chinese coercive activities around Taiwan, as well as the PLA Air Force’s intrusions into Taiwan’s Air Defence Identification Zone (ADIZ). This emphasis may be attributed to Minister Kihara’s pro-Taiwan inclination and his background, which includes his participation in an unofficial Japanese delegation to Taiwan in 2022.[5] This delegation met with Taiwanese officials to discuss evacuation plans for Japanese citizens in the event of a Chinese invasion. The Digest also expresses concern over increasing military cooperation between China and Russia, highlighting recurring joint air force and naval exercises around Japan as implicit demonstrations of ‘force’.

Japan Self-Defence Capability-Assessment

The above comments of the Japanese Defence Minister, duly acknowledging China’s increased military capabilities, and expressing a willingness to address this challenge which includes the development of ‘stand-off defence capabilities, certainly signifies a shift away from Japan’s ‘exclusively defence-oriented’ post-World War II policy, towards a more assertive stance. While Japan’s pacifist Constitution limits the recourse to any direct military action, the country is exploring alternative strategies to enhance its defence capabilities without compromising its principles. Obviously, however, this is easier said than done.

The ‘DOJ-24 Digest’ reflects Japan’s commitment to increasing its defence expenditure to two per cent of its GDP, to generally align with NATO standards. Accordingly, the Japanese government’s plan to raise the defence budget to 43 trillion Yen (about US$ 273 billion) over five years, starting in Fiscal 2023, aims to bolster Japan’s defence posture. However, certain Japanese media reports, indicate that about 130 billion Yen (US$ 804 million) from the allocated fund, may have gone unspent in 2023.[6] This inability to expend the budgeted amount could suggest the existence of systemic problems with regard to budget utilisation and the related implementation plans.

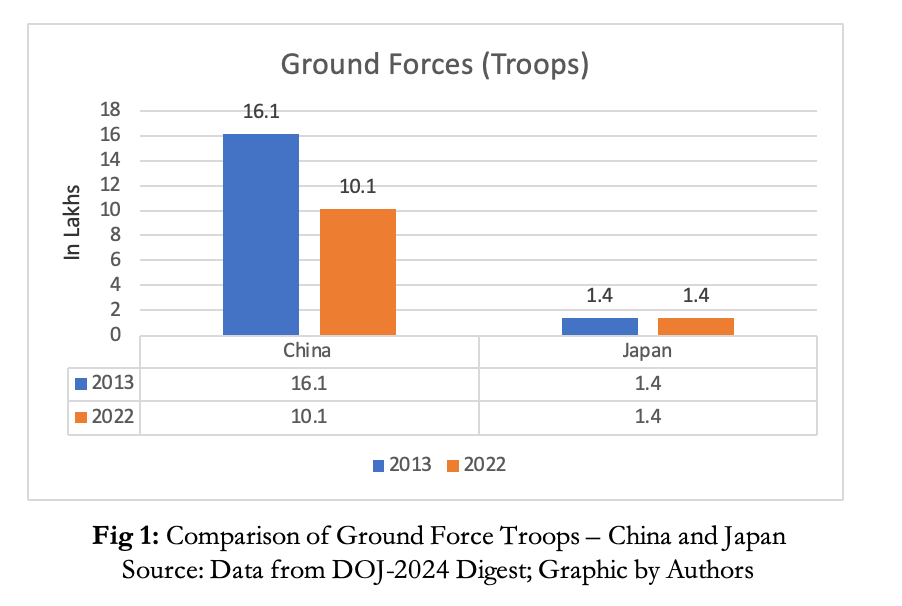

The ‘DOJ-24 Digest’ particularly focuses on several critical areas that need to be addressed, in order to bolster Japan’s national security. These include an urgent need to address the recruitment and staffing concerns for its SDF. This issue has gained prominence in view of Japan’s severe human resource shortage, exacerbated by an ageing population and declining birth rate. The resultant demographic crisis has led to fierce nationwide competition amongst various employers, for scarce human resources, making it extremely difficult for the SDF to attract and retain domain-specific talent. A comparative analysis of Japan’s and China’s military capabilities over a period of nine years from 2013 to 2022, specifically in terms of troop strength, is shown in Figure 1.

Even a perfunctory glance at the SDF’s current manpower situation vis-à-vis Japan’s envisioned military capabilities reveals a troubling trend. Japan’s ground force troop strength has remained virtually unchanged over the past nine years. It is also evident from Figure 1 that, in terms of ground force troops’ strength, while Japan has maintained 1.4 lakh troops, China, despite a reduction of close to 6 lakh army personnel as part of its ongoing reforms, still has a significantly larger number of approximately 10.1 lakh. When viewed through the lens of China being Japan’s primary adversary, this huge troop imbalance presents Tokyo with quite a dismal scenario — one with obvious and ominous portents. In terms of absolute numbers, the troop strength deficit works out to an astounding 8.7 Lakhs.

Even a perfunctory glance at the SDF’s current manpower situation vis-à-vis Japan’s envisioned military capabilities reveals a troubling trend. Japan’s ground force troop strength has remained virtually unchanged over the past nine years. It is also evident from Figure 1 that, in terms of ground force troops’ strength, while Japan has maintained 1.4 lakh troops, China, despite a reduction of close to 6 lakh army personnel as part of its ongoing reforms, still has a significantly larger number of approximately 10.1 lakh. When viewed through the lens of China being Japan’s primary adversary, this huge troop imbalance presents Tokyo with quite a dismal scenario — one with obvious and ominous portents. In terms of absolute numbers, the troop strength deficit works out to an astounding 8.7 Lakhs.

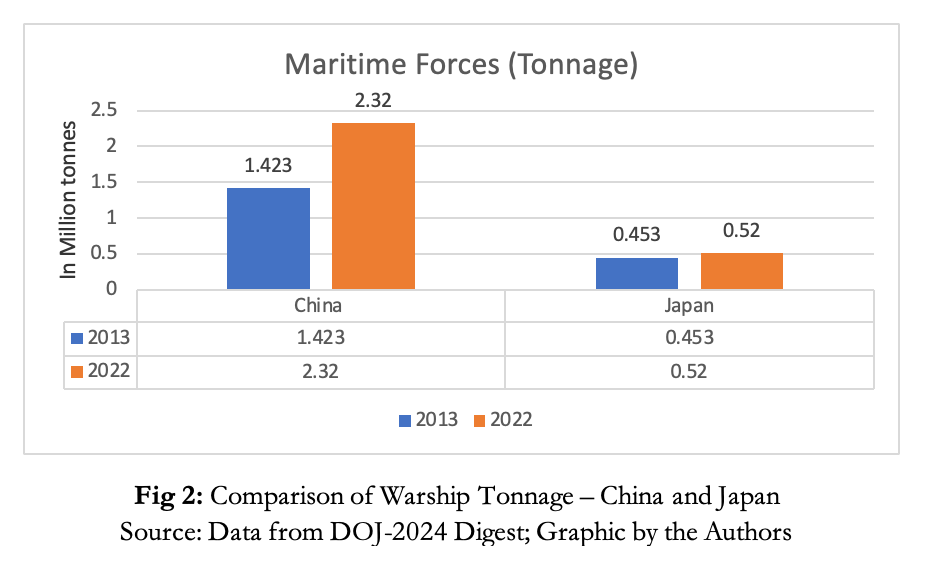

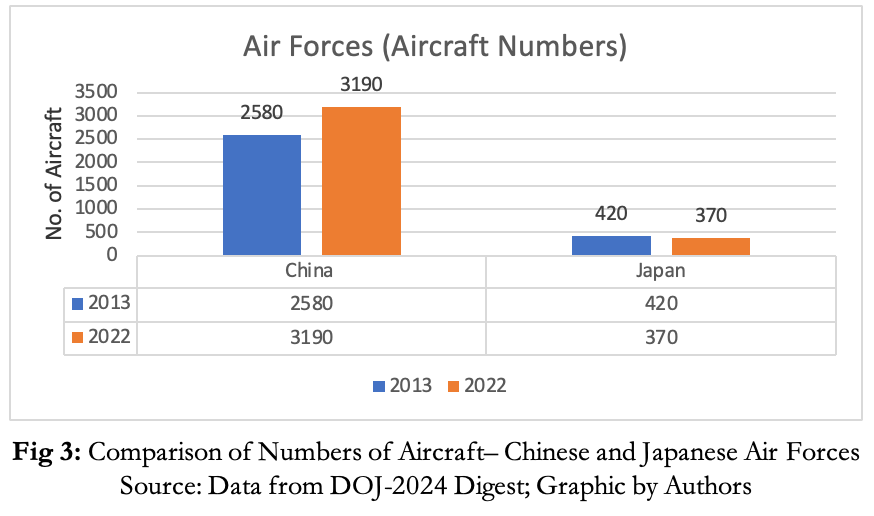

Further, a comparison of two specific parameters — naval ship tonnage and the number of aircraft in their air forces — between Chinese and Japanese military capabilities is presented in Figures 2 and 3 respectively.

It may be seen from Figure 2 that Japan’s warship tonnage has increased slightly, from 0.453 million tonnes in 2013 to 0.52 million tonnes in 2022 — an increase of 14.8 per cent. In contrast, China’s maritime forces have expanded by 63 per cent in total tonnage in conformance with Beijing’s extensive naval build-up. When seen in terms of absolute numbers, an increase of 897,000 tonnes (0.897 million tonnes) in the PLA navy as against a modest increase of 67,000 tonnes (0.067 million tonnes) in the JMSDF — a quantitative differential of more than 13 times — the comparison presents quite a telling picture. This rapidly widening trend, when dovetailed into the holistic ongoing expansion of China’s military capabilities and commensurate manpower and viewed against the backdrop of assertive military and grey zone tactics employed by the Chinese maritime forces in the areas of mutual disputes, assumes disconcerting dimensions.

As regards their respective air forces, Japan has in fact, seen a decline in the number of aircraft, reducing from 420 in 2013 to 370 in 2022. On the other hand, China’s Air Force aircraft numbers have grown from 2580 in 2013 to 3190 in 2022, an increase of 23.64 per cent. In terms of absolute numbers, an increase of 610 aircraft in the PLA Air Force against a decrease of 50 aircraft in the JASDF, shows an alarmingly widening gap in their respective inventories. This reflects the PLA Air Force’s focus on enhancing its aerial combat capabilities, while those of the JASDF are clearly diminishing. This decline may point to challenges in maintaining or upgrading Japan’s aerial capabilities, possibly influenced by budgetary limitations, or shift in strategic priorities.

It is fairly evident from the above indicative comparison of just three key parameters mentioned in the ‘DOJ-24 Digest’ — strength of ground troops, tonnage of warships, and numbers of Air Force aircraft — that there is growing disparity between the military capabilities of China and Japan. While the quality of certain Japanese military hardware may well be better than that of China, the ever-increasing quantitative gap will probably make up for any relative qualitative differential. If this statement is considered to be a ‘given’, then Japan surely must have other viable strategies to mitigate the threat that China — and possibly North Korea or even Russia in tandem — may pose to its national security.

Threat-Mitigating Strategies

While the ‘DOJ-24 Digest’ outlines some Japanese responses to a potential Chinese aggression, including the development of “counter-attack capabilities” — which suggests a more assertive posture under new Defence Minister Kihara’s leadership — Japan ultimately appears to rely rather heavily on the United States for strengthening its national defence through joint deterrence and response capabilities. At the same time, it seeks collaboration with “likeminded countries and others”, although this is seen as a secondary line of action.

Japan-US Defence Collaboration Arrangement

The ‘DOJ-24 Digest’ emphasises the critical importance of the US-Japan alliance, describing it as the cornerstone of Japan’s national security strategy. This enduring alliance has been instrumental in shaping Japan’s defence policies and providing a viable response to regional threats. At the recent US-Japan Security Consultative Committee (SCC) meeting in Tokyo in July 2024, Japan’s Minister for Foreign Affairs, Yoko Kamikawa, and the Minister of Defence, Minoru Kihara, along with their American counterparts, Antony Blinken and Lloyd Austin, emphasised the vital role of the US-Japan alliance in maintaining peace, security and prosperity, not only in the Indo-Pacific, but globally as well. The discussions involved intensive consultations on the roles and missions of the alliance to enhance deterrence and response capabilities.[7]

The US officials acknowledged the increasingly tenuous security environment in the western Pacific, caused by the actions of certain regional actors, and reiterated the United States’ unwavering commitment to Japan’s defence under Article V of the US-Japan “Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security”, which includes the provision of a nuclear umbrella for Japan’s defence, if necessary.[8] The interlocutors also highlighted Japan’s ongoing efforts to bolster its defence, including the increase in its defence budget, the establishment of a “Japan Self-Defence Forces’ Joint Operations Command” (JJOC), a manifestly increased focus upon cybersecurity, and the development of counterstrike capabilities.

Collaboration with Likeminded Countries

The strategy of collaborating with “likeminded countries and others” towards the achievement of Japan’s defence objectives — when compared to its holistic and all-encompassing security arrangements with the US — appears to have been included in the ‘DOJ-24 digest’ as an afterthought. This broad assertion stems from the fact that South Korea is the only country mentioned as a ‘likeminded’ one.

While the ‘DOJ-2024 digest’ does refer to Tokyo engaging with many other countries in “… multilateral and multi-layered defense cooperation…” with an aim to “… create a security environment that does not tolerate unilateral changes to status quo …”[9]— without specifically naming China — it does not make any mention of multilateral fora such as the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) or the ASEAN Defence Ministers Meet Plus (ADMM+). There is just a passing mention of its ‘Free and Open Indo-Pacific’ (FOIP) construct, with the assertion that the Japanese SDF has been contributing towards multilateral anti-piracy measures to ensure maritime security.

India’s Standing in Japan’s National Security Calculus

As indicated earlier, the ‘DOJ-2024 Digest’ mentions only South Korea by name but is silent in terms of specifying other “likeminded countries”. Further, while the QUAD is mentioned in the context of the US playing a stellar role therein, the omission of India and Australia — which are the other two poles in the QUAD construct — is quite conspicuous. Consequently, it does leave the Indian strategic community more than a little perplexed about the possible enabling role that Japan envisages for India, as regards regional security in general, and its national security calculus in particular. In fact, the Indian Ocean — where India, as a resident power of consequence, considers itself to be the preferred maritime security partner and first responder — finds no mention at all in the ‘DOJ-2024 Digest’. To extend this observation further, there is only a single mention of the Gulf of Aden and the Somali offshore area in the context of ongoing counter-piracy operations. This tends to give the impression that the Indian Ocean itself forms just a minuscule part, if any, of Japan’s maritime security concerns.

To be fair, the ‘Defence of Japan-2023’ White Paper did mention India as an important country with whom Japan was progressing substantive defence cooperation activities.[10] Additionally, Japan also considered “defence equipment and technology cooperation” as an important facet of its “special strategic and global partnership” with India.[11] A joint statement issued after the conclusion of the third India-Japan 2+2 (Foreign and Defence Ministers) meeting on 20 August 2024, in fact, noted the satisfactory progress of various ongoing bilateral multi-layered forums — Defence Policy Dialogue, Foreign Office Consultations (FOC), Vice Minister/Foreign Secretary level Dialogue, the Disarmament and Non-Proliferation Dialogue, the Cyber Dialogue, the India-Japan Joint Working Group on Counter-Terrorism, being some of them.[12] Further, the Foreign and Defence Ministers of both sides “… expressed their satisfaction with the seventh India-Japan Joint Working Group on Defence Equipment and Technology Cooperation” and also “… concurred on accelerating future cooperation in defence equipment and technology.”[13]

However, there is very little information on specific cooperative activities being pursued within the above bilateral mechanisms. While participation in some combined air Force exercises like the ‘TARANG SHAKTI-2024’ and combined naval exercises such as ‘JIMEX’ and ‘MALABAR’, mentioned in the ‘Joint Statement’ do appear in the public domain, the much-required acceleration in “defence equipment and technology cooperation”, has still not acquired any significant momentum. Notwithstanding the mention of India in the ‘Defence of Japan-2023’ White Paper in positive terms, and similar thought-process discernible from the ‘Joint Statement’ post the just concluded India-Japan 2+2 Foreign and Defence Ministerial Meet, Indian strategic analysts often wonder as to why the commitments mentioned on paper so unequivocally do not translate into any substantial and meaningful practical defence cooperation on the ground.

Conclusion

The ‘DOJ-24 Digest’ presents a bird’s eye view of the challenges that Japan faces, and its defence strategies in an increasingly complex regional security environment. It highlights the threats posed by China, North Korea, and Russia, underscores the importance of the US-Japan alliance, and outlines Japan’s own efforts to enhance its defence capabilities. The extensive attention given to the US partnership — especially the reliance on the US nuclear umbrella as a key deterrent — highlights Japan’s dependence on American military power and support. This reliance contrasts with the symbolic ‘Swordsmith’ image depicted on the cover page of the ‘DOJ-2024 Digest’ that tacitly implies a more autonomous approach to its national security. This contradiction raises doubts about the coherence of Japan’s defence narrative and appears to potentially overshadow the country’s own initiatives and contributions in this direction. The document nevertheless reveals areas where Japan needs to strengthen its internal governance, and address systemic human resource issues within the Defence Ministry and SDF. Japan well realises that as it navigates these challenges, it will need to balance its present overreliance on US support and will have to make strenuous efforts to bolster its own indigenous defence capabilities so as to ensure a coherent and sustainable defence strategy for the future.

It is felt that the ‘DOJ-2024 Digest’ could have better aligned its thematic elements to reflect a more balanced portrayal of Japan’s defence strategy and its partnership with the US. One must of course, be mindful of the fact that this document is only a brief summary of the main “Defence of Japan-2024” White Paper which, as seen from the previous editions, often runs into 700-800 pages, is likely to cover these critical issues in far greater detail. Consequently, this article, which offers a critical review of the ‘DOJ-24 Digest’ alone, can, at best, be taken as an initial indicative piece. There would, of course, be a need for an updated and comprehensive review once the entire text of the “Defense of Japan-2024” White Paper is placed in the public domain.

******

About the Authors

Captain Kamlesh K Agnihotri, IN (Retd) is a Senior Fellow at the National Maritime Foundation (NMF), New Delhi. His research concentrates on the manner in which the maritime ‘hard security’ geostrategies of India are impacted by those of China, Pakistan, Russia, and Turkey. He also delves into holistic maritime security challenges in the Indo-Pacific and their associated geopolitical dynamics. Views expressed in this article are personal. He can be reached at kkumaragni@gmail.com

Ms Aashima Kapoor is a Junior Research Associate at the National Maritime Foundation. Her research focuses on the manner in which the maritime geostrategies of India are impacted by those of Japan. In addition to her research expertise, she is proficient in the Japanese language. She can be reached at ea2.nmf@gmail.com

Endnotes:

[1] Japan Ministry of Defence, “DEFENCE OF JAPAN-2024 Digest (Annual White Paper)”, https://www.mod.go.jp/en/publ/w_paper/index.html

[2] Japan Ministry of Defence, “2024 DEFENCE OF JAPAN Pamphlet”, https://www.mod.go.jp/j/press/wp/wp2024/pdf/DOJ2024_Digest_EN.pdf

[3] Japan Ministry of Defence, “DEFENCE OF JAPAN-2024 Digest (Annual White Paper)”, https://www.mod.go.jp/en/publ/w_paper/index.html

[4] Dzirhan Mahadzir. “Japanese Defence White Paper Warns Pacific at Greatest Risk Since WWII” USNI News, https://news.usni.org/2024/07/12/japanese-defense-white-paper-warns-pacific-at-greatest-risk-since-wwii.

[5] Agence France-Presse (AFP) and Kyodo “Japan’s Kishida Taps Pro-Taiwan MP as New Defence Minister in Cabinet Shake-Up” South China Morning Post, September 13, 2023, https://www.scmp.com/news/asia/east-asia/article/3234364/japans-kishida-taps-pro-taiwan-mp-new-defence-minister-cabinet-shake.

[6] The Asahi Shimbun, “Unspent defence funds will total 130 billion yen for fiscal 2023”, July 11, 2024, https://www.asahi.com/ajw/articles/15341893

[7] U.S. Department of Defence, “Joint Statement of the Security Consultative Committee (2+2)”, July 28, 2024, https://www.defense.gov/News/Releases/Release/Article/3852169/joint-statement-of-the-security-consultative-committee-22/.

[8] Ibid

[9] ‘DOJ-2024 Digest’ ibid, p.26.

[10] Japan Ministry of Defence, “DEFENCE OF JAPAN-2023 Digest (Annual White Paper)”, p. 410, https://www.mod.go.jp/en/publ/w_paper/wp2023/DOJ2023_EN_Full.pdf

[11] Ibid, p. 480.

[12] Ministry of External Affairs, “Joint Statement: Third India-Japan 2+2 Foreign and Defence Ministerial Meeting”, August 20, 2024, https://www.mea.gov.in/bilateral-documents.htm?dtl/38190/

[13] Ibid.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!