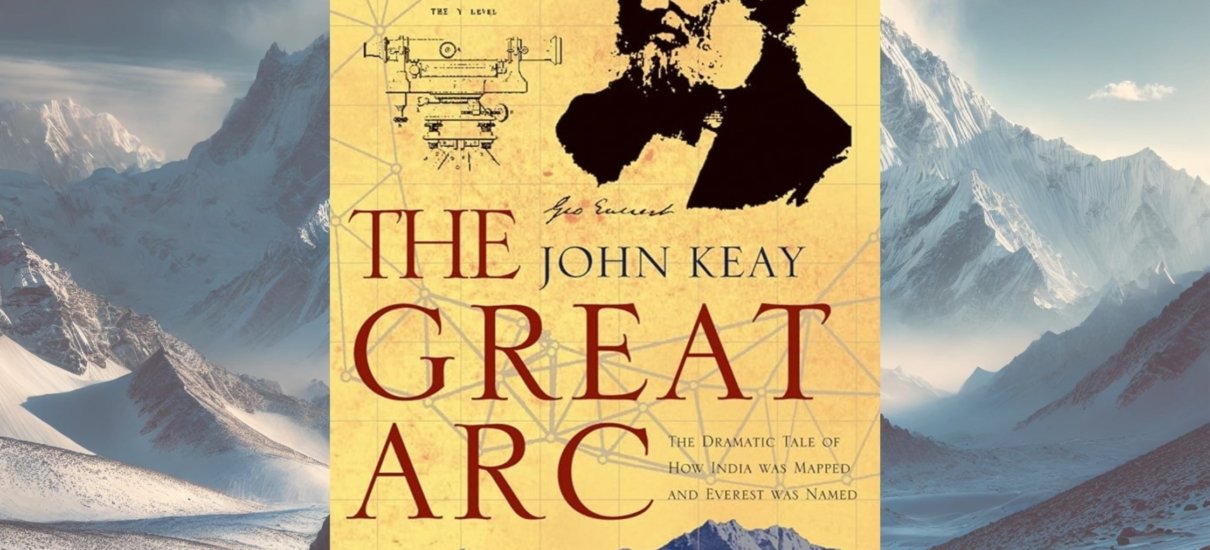

John Keay, London: HarperCollins, 2000. 276 pages ISBN 9780002570625.

John Keay is a distinguished British historian, journalist, and author. He is recognised for his extensive work on the history of India and geographical exploration. Over a career spanning more than four decades, Keay has established himself as a leading authority on the history of the British Empire, particularly in South Asia. His notable works, including “India: A History and The Honourable Company: A History of the English East India Company”, garnered widespread acclaim for their meticulous research and engaging narrative style. The author’s strength lies in his ability to weave complex historical narratives with clarity and insight, making intricate subjects accessible to a broad audience.

In “The Great Arc: The Dramatic Tale of How India Was Mapped and Everest Was Named”, Keay turns his attention to one of the 19th century’s most ambitious scientific undertakings — the Great Trigonometrical Survey of India (GTS). This monumental project — led by British officers William Lambton and George Everest — sought to map the Indian subcontinent with great accuracy. The survey not only revolutionised cartography and geodesy but also played a crucial role in the expansion of British imperial control, thereby providing the detailed maps necessary for administration, taxation, and military usage.

Keay’s treatment of “The Great Arc” reflects his deep understanding of the historical, scientific, and imperial contexts that shaped the GTS. He vividly highlights the challenges faced by the surveyors (from traversing hostile terrain to battling tropical diseases), while also delving into the personal sacrifices and motivations of key figures like Lambton and Everest. By exploring the human element behind the scientific rigour, Keay effectively captures the intersection of science, exploration, and empire by offering readers a nuanced account of this extraordinary achievement.

Central to Keay’s narrative is his portrayal of the GTS as more than just a technical feat; it is presented as a testament to human perseverance in the pursuit of knowledge. The unwavering commitment to precision on the part of the surveyors, despite enormous challenges, is a recurring theme of the book. Keay’s detailed descriptions of the methods employed —triangulation and the use of theodolites — underscore the scientific rigour that underpinned the GTS. This achievement holds significance not only for cartographers but also for the broader field of scientific exploration, as the GTS set new standards for accuracy and influenced future surveys worldwide.

However, Keay’s narrative is not without critical undertones. He acknowledges the GTS’s role within the broader context of British imperialism, wherein detailed maps produced after the survey were instrumental in solidifying colonial rule in South Asia. Keay does not shy away from exploring the darker aspects of this enterprise, raising important questions about the relationship between science and empire. The GTS, while a monumental scientific accomplishment, also served as a tool of imperial domination, facilitating the exploitation of India’s resources and the oppression of its population.

A notable criticism of the book is the narrow focus on the British perspective, with insufficient attention given to the Indian assistants and labourers who played critical roles in the GTS. These individuals, who often faced the greatest dangers and endured gruelling work environment, are invisible in the narrative. This oversight continues to perpetuate a colonial narrative that credits only the British with the success of the survey, overlooking the contributions of the Indian workers. Moreover, Keay occasionally romanticises the survey and its leaders, glossing over problematic aspects of their survey, particularly in consolidating British colonial rule in India. A critical examination of the ethical implications of the survey, and its impact on the Indian population, would have added the much-needed depth to the narrative.

Additionally, while Keay’s detailed descriptions of the technical aspects of the GTS are essential to understand its significance, they may overwhelm readers unfamiliar with geodesy and the related terrestrial survey tools and instruments. The dense technical details, while informative, could detract from easy assimilation of the book’s context to a general audience. When situating “The Great Arc” within the broader context of maritime and imperial studies, it becomes pertinent to compare it with similar works that examine the relationship between scientific advancement, territorial discovery, and colonial expansion. This book distinguishes itself through its engaging narrative and thorough historical analysis, while also resonating with broader scholarly critiques of how scientific endeavors have been used to further imperial control.

Even in the era of GPS and advanced navigation tools like Google Maps, it is useful to reflect upon the transformative journey of mapping and navigation technologies. Today’s generation has grown up relying on satellite-based systems that provide instantaneous location data, significantly simplifying navigation; and they seldom have background knowledge about the labour-intensive surveying and mapping methods employed during the Great Trigonometrical Survey era of yore. The earlier tools, which included theodolites, triangulation methods, and manual cartographic techniques, demanded immense manpower and meticulous effort to achieve even a fraction of the precision that modern computational software offers. These older practices not only required skilled surveyors to traverse challenging terrains but also embodied a deep understanding of geography and mathematics that has largely been automated in contemporary systems. This evolution highlights the remarkable advancements in technology and the ways in which the foundations laid by historical surveys, like the GTS, have paved the way for today’s sophisticated mapping capabilities, fostering an appreciation for the dedication and ingenuity of those who came before us.

In conclusion, “The Great Arc” is a significant contribution to the literature on the history of cartography, the British Empire, and the interplay of science and imperialism. Keay’s meticulous research and captivating storytelling bring to life the challenges and triumphs of the GTS, offering readers a balanced perspective on both its scientific achievements and its role in British colonialism. However, the book’s shortcomings—its limited focus on the Indian perspective and its occasional romanticisation of the British surveyors—suggest that it does not provide a complete picture of the GTS. Despite this criticism, “The Great Arc” remains an important work, ensuring that the story of this remarkable achievement is not forgotten. For those interested in the intricate connections between scientific progress, exploration, and imperial expansion as well as the linkages between modern and older concepts of cartography, mapping and terrain depiction, Keay’s book offers both insight and appreciation for these former technological frontiers, compelling readers to consider the broader implications of scientific endeavours within the context of imperial history.

******

About the Reviewer:

Ms Muskan Rai is a Junior Research Associate at the National Maritime Foundation (NMF). She graduated in History from Ramjas College, University of Delhi, and completed her post graduation in “International Relations, Security and Strategy” from the OP Jindal Global University. Her research interests include maritime history, multi-disciplinary maritime studies and India’s maritime relations with East Asia. She can be reached at rsf3.nmf@gmail.com.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!