Abstract

Ballast water, crucial for safe maritime operations, poses significant risks by transporting various marine species, leading to ecological disruptions and bio-invasions. The inadvertent transfer of these species has caused widespread environmental degradation. However, the shipping industry faces significant challenges in respect of the technological, ecological, economic, and health impacts of using seawater as ballast. Consequently, much interest is being evinced within the shipping industry in the concept of ballast-free vessels as a promising solution to these challenges. A switch to ballast-free vessels offers a fascinating strategy to mitigate the adverse impacts associated with traditional ballast water management practices. This article is the first of a two-part series aiming to explore the IMO’s mandatory stipulations in respect of ballast water. It introduces the concept of ballast-free vessels, and touches upon their potential advantages and challenges. Part 2 of this series will delve into the details of ballast-free vessels and the experience of the shipping industry thus far in adopting this alternative solution to the problem of ballast water management. Designed as a “White Paper” under the L&T Fellowship at the National Maritime Foundation, this two-part document seeks to meaningfully contribute to the discourse on protecting our oceans and preserving its marine ecosystems.

Keywords

Ballast Water Management, Ecological Ramifications, Invasive Species, Ballast-free Vessel, Sustainable Maritime Practices.

***

The use of water as ballast in steel-hulled vessels has been a fundamental aspect of maritime operations, ensuring that ships maintain stability, manoeuvrability, and safety as they navigate the world’s oceans. This practice involves the periodic intake and pumping-out of seawater into ships’ ballast tanks to counterbalance weight changes due to variations in cargo load, fuel, and water consumption. While indispensable for the safe and efficient functioning of modern shipping, the ballasting process inadvertently serves as a conduit for the global translocation of a myriad of marine micro-organisms, ranging from microscopic bacteria and microbes to small invertebrates, eggs, cysts, and larvae of various species. As ships discharge ballast water in new ports, they can (and do) introduce non-native species into foreign ecosystems, where they may thrive, out-compete indigenous species, and precipitate ecological and economic disruptions.[1]

The ecological ramifications of ballast water-mediated bio-invasions first came to light following the mass occurrence of the Asian phytoplankton algae Odontella (Biddulphia Sinensis) in the North Sea in 1903, marking a pivotal moment in human understanding of these phenomena. However, it was not until the 1970s that the scientific community began to systematically address the issue, with significant concerns being raised by the late 1980s, particularly by countries such as Canada and Australia, which were directly affected by invasive species. These concerns were escalated to the International Maritime Organization’s “Marine Environment Protection Committee” (MEPC), emphasising the growing international alarm over the issue. Despite increased awareness and regulatory efforts, the problem of invasive species, facilitated by the burgeoning volumes of seaborne trade, continues to escalate, threatening biodiversity and human health in newly invaded areas. This ongoing crisis highlights the urgent need for innovative solutions, such as ballast-free vessels, to prevent further ecological damage while maintaining the global shipping industry’s operational requirements.[2]

Invasive Species and Ballast Water

The expansion of non-indigenous species beyond their natural habitats is driven by the increased movement of goods and people, which is itself facilitated by increasing globalization. This results in the inadvertent introduction of “non-indigenous aquatic species” (NIASs) into new environments through human activities. Some of these NIASs can establish populations that spread, posing potential risks to ecosystem integrity, biodiversity, socio-economic values, and human health. These invasive species, also generically referred-to as “harmful aquatic organisms and pathogens” (HAOPs), are widely acknowledged for the significant threat that they pose to biodiversity and economic interests. HAOPs possess the ability to disrupt ecosystem processes, devalue water resources for human use, and trigger various socio-economic repercussions. Consequently, the global management of HAOPs is critical, especially considering the escalating trends in global trade, which amplify the risks associated with the spread of these organisms.[3]

Invasive species pose a significant threat to the conservation and sustainable utilisation of global, regional, and local biodiversity, exerting considerable adverse impacts on the ecosystem services provided by natural habitats. This trend is rapidly breaching biogeographic barriers critical for the maintenance of global biodiversity, leading to increased homogenisation. The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) underscores the urgent need to identify and prioritise invasive alien species and pathways by 2020, with targeted efforts to control or eradicate priority species and implement measures to manage pathways, thereby preventing their introduction and establishment. For instance, in India’s historical context, the introduction of English Trout (Salmo Trutta Fario Linnaeus) in 1863 marked the beginning of a series of introductions of various alien species into the country’s aquatic ecosystems. This has culminated in a diverse array of alien species, enriching India’s aquatic resources but also necessitating vigilant management strategies.[4]

Ballast water serves as a critical element in ensuring the safe operation of ships by facilitating stability and manoeuvrability. Historically, solid materials like rocks and sand were used. However, the adoption of water as ballast material became prevalent due to its convenience and accessibility. Annually, approximately 10 billion tons of ballast water are discharged globally. Nevertheless, the discharge of untreated ballast water poses significant environmental and economic risks as sediment and various organisms, including bacteria, microbes, and larvae, are carried within it.[5] Upon discharge, these organisms may thrive in new environments, potentially becoming invasive species. Consequently, ballast water discharge from ships on international voyages has caused the invasion of alien organisms and has been listed as one of the four major hazards of the ocean by the Global Environmental Protection Fund (GEF).[6]

The introduction of invasive species through ballast water discharge has led to substantial ecological and economic damage worldwide. Notable examples include the zebra mussel invasion in the Great Lakes and the introduction of the European Green Crab to Canadian waters.[7] These invasions disrupt local ecosystems, damage infrastructure, and incur considerable cleanup and repair costs.[8]

Ballast Water Management (BWM)

To address the risks associated with ballast water discharge, stringent regulations and management protocols have been implemented globally. For instance, Canada enacted “Ballast Water Regulations” under the Canada Shipping Act, 2001, and ratified the International Maritime Organization’s Ballast Water Management Convention (BWMC). These regulations mandate the installation of ballast water management systems on ships and adherence to specific standards for ballast water treatment and discharge.[9]

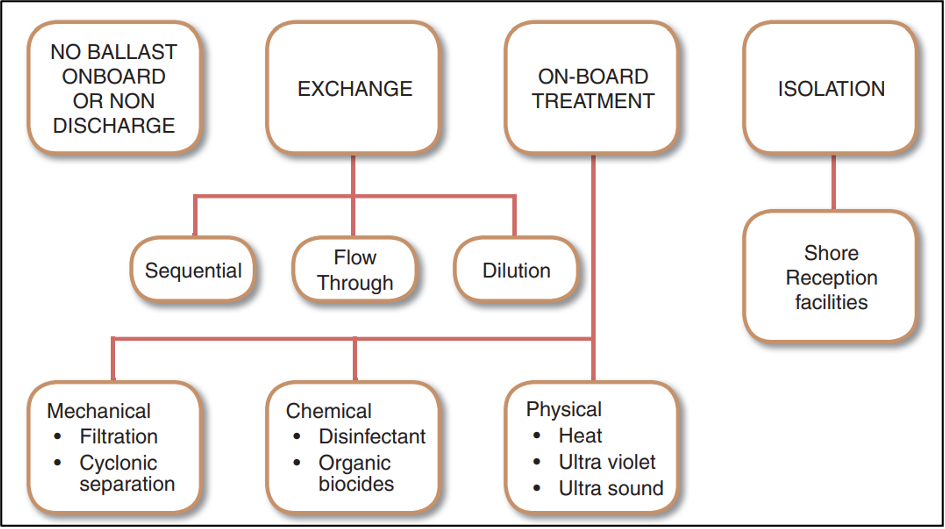

BWM plans play a pivotal role in ensuring compliance with regulations. These plans delineate procedures for the safe management of ballast water and necessitate record-keeping to monitor ballast water exchange and treatment. BWM systems utilise diverse technologies such as filters, chemicals, and ultraviolet light to eradicate harmful organisms from ballast water before discharge. Through a comprehensive two-stage treatment process, solid particles are removed, and potentially harmful marine organisms are destroyed, effectively mitigating the spread of invasive species, and safeguarding marine ecosystems and economies.

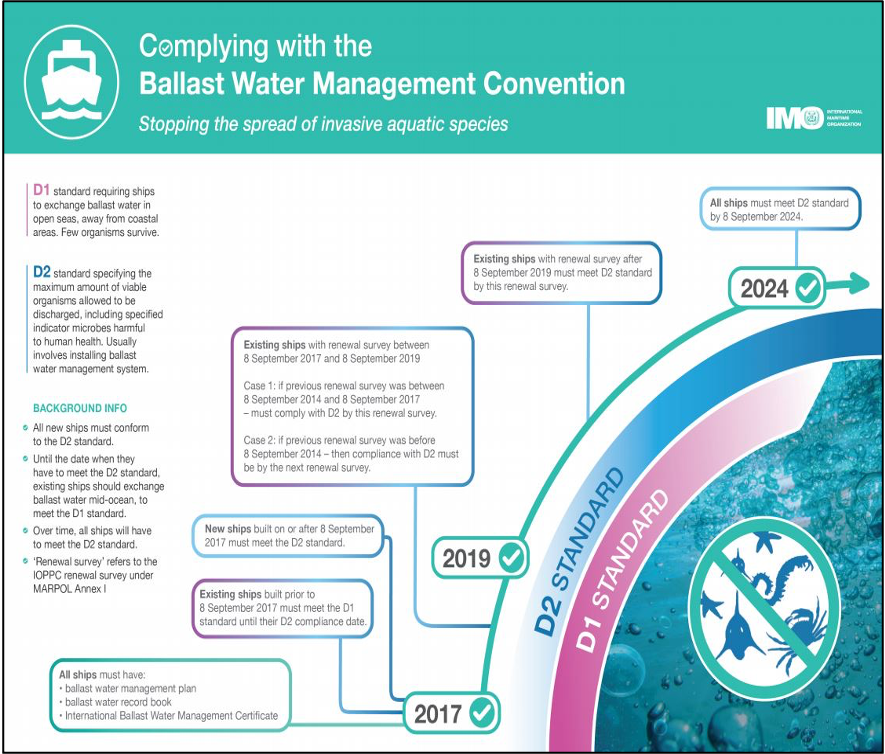

“The International Convention for the Control and Management of Ships’ Ballast Water and Sediments”, which was adopted on 13 February 2004 and entered into force on 08 September 2017, mandates that all vessels engaged in international traffic adhere to specific standards for managing their ballast water and sediments, as stipulated in a vessel-specific ballast water management plan. Additionally, every vessel requires to carry a ‘ballast water record book’ and an ‘international ballast water management certificate’. Thus, all new-build vessels will need to incorporate an on-board ballast water treatment system, while existing vessels will need to have one retrofitted on board. As an interim measure, however, vessels are permitted to conduct mid-ocean “ballast water exchanges”, denoting the flushing-through of their ballast tanks multiple times in deep water and at distances well removed from the coast. The International Maritime Organization (IMO) outlines two primary standards:[10]

- “D1 Standard”. The “D1 Standard” involves a process called Ballast Water Exchange (BWE), where ships are required to achieve a minimum of 95% volumetric exchange of ballast water. This means that at least 95% of the ballast water on board needs to be replaced. Achieving this efficiency involves a method called ‘pumping through’, which requires the ship to pump out and replace the ballast water three times in succession. Moreover, for this operation to be considered compliant, it must occur at least 200 nautical miles away from the shore, and the water depth should be a minimum of 200 metres. While there is some relaxation available for the distance from shore at which compliant ‘pumping through’ needs to occur (a minimum distance of 50 nautical miles appears to be acceptable), there is no relaxation to the minimum depth (which must be 200 metres or more). This notwithstanding, vessels are nevertheless required to communicate with Port State authorities to understand any specific requirements for BWE in local waters.[11]

- “D2 Standard”. The “D2 Standard” (as amended by the 72nd session of the Marine Environment Protection Committee [MEPC 72]) focuses upon the performance of ballast water in terms of its chemical composition and the presence of organisms. To comply with the D2 standard, ships need to obtain a report from an accredited laboratory, confirming compliance with D2 Ballast Water Performance Testing. The aim of this standard is to establish acceptable levels of organisms present in discharged ballast water. The acceptable levels include:

- Discharge fewer than 10 viable organisms per cubic metre, with dimensions equal to or greater than 50 micrometres, and fewer than 10 viable organisms per millilitre, with dimensions less than 50 micrometres but equal to or greater than 10 micrometres.

- Additionally, the discharge of indicator microbes, as a human health standard, must not exceed specified concentrations.[12]

|

Source: International Maritime Organisation[1] |

Shipowners and business managers primarily depend on various ballast water treatment technologies, including heating, electrolysis, and UV treatment, to ensure compliance with regulations. However, there are challenges to be faced. These technologies not only consume significant time and labour but also escalate operational expenses for shipowners and operators. As a result, while addressing the pressing issue of the spread of invasive species, the implementation of ballast water treatment technologies necessitates a careful balance to be struck between regulatory compliance and the economic sustainability of maritime operations.[13] The Group of Experts on the Scientific Aspects of Marine Environmental Protection (GESAMP) has recognised that “the emission of [chlorination related] chemicals coming from ballast water management systems is a rather new potential threat to marine environment”. Consequently, within the framework of the procedure for approval of ballast water management systems utilising active substances (G9), the GESAMP Ballast Water Working Group is actively engaged in assessing systems employing active substances. During this assessment, various models are being applied and tested to evaluate the impact of residual chemicals present in ballast water discharges.[14] Both BWE and Ballast Water Management Systems (BWMS) necessitate the utilisation of robust equipment, leading to the substantial consumption of electricity. This heightened demand for electrical power, in turn, escalates the consumption of heavy fuel oil (HFO) and leads to the additional emissions of pollutants into the atmosphere.[15] Additionally, Class NK has observed several common problems associated with BWMS. These include malfunctions in highly turbid waters, issues with BWMS-related parts, limited lifespan of consumables, and clogging of the ‘total residual ‘oxidants sampling line. Addressing these challenges is essential for ensuring the effective implementation and operation of BWMS to mitigate the spread of invasive species in

|

Source: GloBallast Partnerships[1] marine environments.[16] |

Innovations in Ship Design

The conventional practice of configuring ballast tanks, mainly aimed at enhancing navigational safety and stabilising ships during light loads, has been reevaluated. This reassessment has led to the possibility of innovation in ship design to achieve a higher centre of buoyancy while lowering the centre of gravity, thereby making the ship stable in varying conditions of loading. One such innovation in ship design pertains to the concept of ballast-less tanks (US patent #6694908, 2004), pioneered by Dr Michel Parsons of the University of Michigan, USA. Dr Parsons presented his groundbreaking findings at the annual meeting of the American Society of Shipbuilding and Marine Engineering in 2004, focusing on the design of non-ballasted tanks and the specifics of through-flow system hull technology.[17]

Another innovative ship-design has been propounded by the Shipbuilding Research Centre of Japan (SRC) which, in 2003, introduced a concept known as the “storm ballast ship”, primarily for tankers. This entails a V-shaped hull form with optimised buoyancy distribution. By altering the vertical distribution of hull buoyancy and widening the beam, this design ensures a deeper draught even in light conditions, thereby maintaining stability. The incorporation of a V-shape cross-section minimises the need for ballast water exchange, thereby reducing the risk of introducing invasive species.[18]

Yet another significant innovation is the “Flow System Hull”, which replaces the longitudinal structure below the cargo waterline by a pressurised water tank system. This design feature converts the original closed system to a front and rear open configuration, allowing seawater to flow continuously from the bow inlet to the stern outlet. This flow-through mechanism effectively minimises or eliminates altogether the need for static ballast water tanks. Moreover, the design complies with IMO regulations on marine environmental protection by utilising local seawater and avoiding the transfer of seawater between locations.[19]

Researchers at the University of Michigan have conducted extensive tests on vessels equipped with the “Flow System Hull”. The results demonstrate that these ships maintain stability while utilising seawater flow to additionally enhance propulsion efficiency. With seawater flowing from the front to the rear through large pipes installed at the bottom of the ship, the propeller can accelerate rotation, increase speed, and significantly reduce fuel consumption and emissions. Test results indicate potential fuel savings of up to 7.3%, highlighting the efficiency and environmental benefits of innovative ship design approaches in addressing bio-invasion risks associated with ballast water exchange.[20]

There are clearly exciting times ahead as ship designers attempt to offer alternatives to the standard methods and processes of ballast water management. The central question, of course, is whether the various alternatives being offered by a growing number of ship design firms will in fact be economically viable or whether they will be mere curiosities for history to smile at. Here, as indeed, in every other innovation, the devil lies in the details. It is these details that Part 2 of this article will address.

To be continued in Part 2…

******

About the Author

Ayushi Srivastava is a Research Associate at the National Maritime Foundation (NMF). She holds a BTech degree from the APJ Abdul Kalam Technical University, UP, and an MTech degree in naval architecture and ocean engineering from the Indian Maritime University (IMU), Visakhapatnam Campus. Her current research is focused upon the intersection of technology and shipping, and especially those aspects that support India’s ongoing endeavour to transition from a ‘brown’ model of economic development to a ‘blue’ one. She can be reached at ps1.nmf@gmail.com.

Endnotes:

[1] “Ballast Water Management”, International Maritime Organisation https://www.imo.org/en/ourwork/environment/pages/ballastwatermanagement.aspx

[2] Ibid

[3] Yung-Sheng Chen, Kang Chao-Kai, and Liu Ta-Kang, “Ballast Water Management Strategy to Reduce the Impact of Introductions by Utilizing an Empirical Risk Model” Water 14, No 6: 981, 2022, https://doi.org/10.3390/w14060981

[4] Ramakrishna, “Bio-invasion of Aquatic Invasive Species in India”, in Invasive Alien Species: Observations and Issues from Around the World eds T Pullaiah and Michael R Ielmini, (John Wiley & Sons Ltd., 2021), Volume 2, 38-72

[5] P Ramani and V Sasirekha, “Management of Ballast Water – Ballast Free Shipping – The Way Forward”, AMET International Journal of Management, ISSN 2231-6779, June 2014

[6] Wang Hong and Li Huabin, “Comment on Ballast Free Ship”, International Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences (IJEAS) ISSN: 2394-3661, Volume-5, Issue-12, December 2018 Comment on Ballast Free Ship (researchgate.net)

[7] Markus Frederich and Emily R Lancaster, “The European Green Crab, Carcinus Maenas: Where did they Come from and Why are they Here?”, in Ecophysiology of the European Green Crab (Carcinus Maenas) and Related Species, eds Dirk Weihrauch and Iain J McGaw, United States: Academic Press, 2024, 1-20

[8] Ballast Water Management, International Maritime Organization, https://www.imo.org/en/ourwork/environment/pages/ballastwatermanagement.aspx

[9] Ballast Water Regulations, Transport Canada, Government of Canada, Ballast Water Regulations – Canada.ca

[10] “Ballast Water Management Convention Aims to Stop the Spread of Potentially Invasive Aquatic Species in Ships’ Ballast Water”, International Maritime Organisation, 08 September 2017

https://www.imo.org/en/MediaCentre/PressBriefings/Pages/21-BWM-EIF.aspx

[11] International Convention for the Control and Management of Ships’ Ballast Water and Sediments (BWM), International Maritime Organisation,

[12] Ibid

[13] Wang Hong and Li Huabin, “Comment on Ballast Free Ship”, International Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences (IJEAS). 5. 10.31873/IJEAS.5.12.05

[14] Ballast Water Working Group, Joint Group of Experts on the Scientific Aspects of Marine Environmental Protection (GESAMP), http://www.gesamp.org/work/groups/34

[15] Identifying and Managing Risks from Organisms Carried in Ships’ Ballast Water, GloBallast Monograph Series Nov 21, GloBallast Partnerships Project Coordination Unit, International Maritime Organization and World Maritime University (WMU), 2013, https://wwwcdn.imo.org/localresources/en/OurWork/PartnershipsProjects/Documents/Mono21_english.pdf

[16] Ballast Water Management Convention, Class NK, https://www.classnk.or.jp/hp/en/activities/statutory/ballastwater/index.html

[17] Michael G Parsons, Miltiadis Kotinis, Thomas Lamb, and Ana Sirviente, “Development and Investigation of the Ballast-Free Ship Concept”, Transactions of SNAME, Vol 112 (2004): 206-240

[18] Avinash Godey, SC Misra, and OP Sha, “Development of a Ballast Free Ship Design”, International Journal of Innovative Research & Development, Vol 1 Issue 10, December 2012

[19] Wang Hong and Li Huabin, “Comment on Ballast Free Ship”, International Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences (IJEAS), DOI: 10.31873/IJEAS.5.12.05

[20] Ibid

Fig 1. IMO Ballast Water Management Convention

Fig 1. IMO Ballast Water Management Convention Fig 2. Ballast Water Management Options

Fig 2. Ballast Water Management Options

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!