Keywords: Critical Maritime Infrastructure, Telecommunication Bill 2022, Submarine Cables, Network Management Systems, Cable Landing Station

The Telecom Regulatory Authority of India’s (TRAI) recent recommendations on the licensing framework and regulatory mechanism for submarine cable landing in India signals the growing regulatory attention that the submarine cable system is receiving.[1] A key recommendation is to “include a section in the Indian Telecommunication Bill 2022 (“Telecom Bill 2022”) to promote, protect, and prioritise ‘Cable Landing Station’ and ‘submarine cable’ in India.”[2] The aim of this article is to highlight that legislation on communication cables must be comprehensive and holistic, particularly when viewed through the security lens. In order to be so, it must address the vulnerabilities of each layer of the cable system which, while not compartmentalised, do have distinct features. A manifestation of the vulnerability of any one layer can compromise the entire system and, therefore, it is necessary to ensure that legislation and its subordinate regulations plug all the holes. This article speaks to policymakers in India engaged in the protection of submarine cable, in particular the National Security Council Secretariat and the Department of Telecommunication. In its analysis the article first disaggregates the submarine cable system into three layers and highlights the vulnerabilities of each one. It then proceeds to analyse India-relevant protective measures that need to be undertaken so as to address each layer. The role that the law plays in both, creating vulnerabilities and plugging them, is then explored in reference to the legal systems of India, the United States of America, the United Kingdom, and the People’s Republic of China.

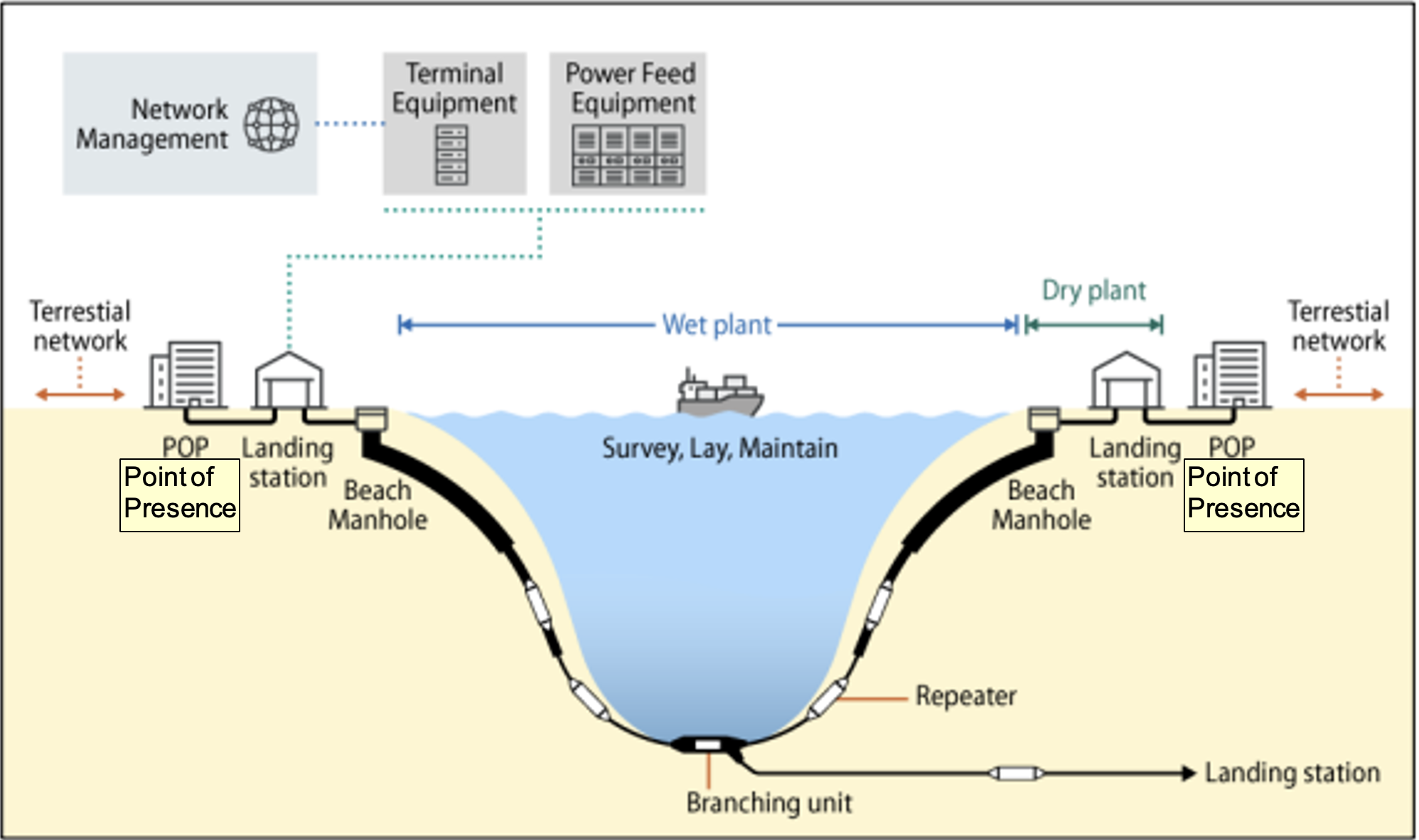

Fig 1: Submarine Communication Cable System and its Components

Source: Congressional Research Service, Undersea Telecommunication Cables: Technology Overview and Issues for Congress

The System and Its Layers

Submarine Communications Cable Systems, the backbone of the modern-day internet, like other telecommunication systems can broadly be categorised in three layers, viz., a ‘physical’ layer, a ‘logical’ layer, and an ‘information’ layer.[3] The physical layer consists of the hardware components of the system such as the fibre-optic cable, inbuilt repeaters as signal boosters, branching units to different terminals, and the submarine line terminal equipment (SLTE) housed in the onshore Cable Landing Stations (CLS) at both ends.[4] The SLTE receives signals from the undersea optic-fibre cable and transmits them further inland to terrestrial networks for transmission to the end-user.[5] In addition to the SLTE, the CLS houses the Power Feed Equipment which provides direct constant electric supply to power the repeaters (these repeaters are essential to ensure signal transmission across the entire length of the cable).[6] While the power feed can be single- or double-ended (current flowing from either one or both terminals), power feeds for branching units are generally single-ended.[7] In addition to the optical signal path, the cable also carries a power feeding path along the main cable and the branching units.

The logical layer of the cable system is responsible for the management of data transmission and ensures the routing of data to its destination. In a submarine communications cable system, this is in the form of a ‘network management system’ (NMS), which provides centralised, network-based control over the physical layer of the system.[8] Through the NMS, operators can remotely monitor and control the different components of the cable system, which includes not only the data transmission but also the power feed equipment. [9] Newer versions of NMSs can in fact manage multiple cable systems from a centralised platform, with unified management systems becoming the new norm.[10] Cost and operational effectiveness of networked, remote management systems has pushed private enterprises to adopt such systems despite the increased vulnerability due to centralisation.[11]

The information layer consists of the actual data packets being transmitted through the cable system, and includes the entire spectrum from personal communications, financial transactions, governmental data, and diplomatic communications. The information can be viewed as a distinct layer from the logical layer which concerns itself more with the management of data flow. While data security is an entire separate area of study, this paper focuses on the threat to the data at the point of the submarine cable system.

As would be evident, each segment of the cable system presents its own vulnerabilities that can be targeted either individually or in conjunction with one another. The future of warfare is ‘hybrid’ with both physical and cyber components, and submarine cable systems are vulnerable to both.

Vulnerabilities of the Physical Layer

The physical layer of the cable system faces broadly two types of threats, viz., natural, and anthropogenic. Natural threats emanate from natural disasters such as earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, etc. On the other hand, anthropogenic threats, i.e., threats from human activities, may be accidental or intentional. Accidental damage to cables stems predominantly from fishing and anchorage activities close to the coast. Intentional damage is one caused by non-State or State actors with the intention of either theft of the cable wires or sabotaging communications of a State. This threat is more sinister and needs particular attention by the State.[12]

Vulnerabilities in the Network Management System

An integrated, internet-connected NMS must contend with grave attendant operational and logical security risks to the communications cable system. Growing cable connections, data transmissions, and telecom players have all brought with them greater complexity in data management. Hence, NMS are equipped with Reconfigurable Optical Add/Drop Multiplexing technology, which allows for greater flexibility in the management of the data network and traffic, especially between the main cable and Branching Units (BU).[13] Each BU has a specific wavelength band in which data is transmitted, and which can be modified.[14] This allows an operator who has access to the NMS, to activate or block specific wavelengths which, if used with sinister intent, could completely disrupt the flow of data to a particular branching unit, and has the potential of isolating entire countries connected by the branching unit.[15]

Further, since even the monitoring of the cables is done through the NMS, a ‘hacker’ could prevent the system from displaying any faults that may have occurred, and temporarily disrupt data without the knowledge of the operator.[16] Moreover, such access could also enable the hacker to disrupt the power feeder equipment thus cutting off electricity supply to the repeaters, especially in a branching unit.

This can happen without physical proximity to the cable landing station, due to inbuilt remote access capabilities through the internet, making it easier and more cost-effective to undertake.[17] It is prudent to highlight that each NMS service provider may have different capabilities and security mechanisms in-built into its systems. It is indeed possible for systems to have secure networks running on a different protocol, which make them more secure from attempts to access and disrupt.[18] However, this is not standard industry practice. Rather, most NMS service providers use common operating systems such as Windows/Linux, and TCP/IP to connect to the network operation centre.[19] The vulnerabilities of these systems are already well understood and have a high probability of being successfully exploited. A lack of minimum standards, coupled with ownership by private industry that almost invariably has cost-effectiveness as its primary objective, increase the likelihood of the adoption of such insecure systems for this form of critical infrastructure.

Such attacks are not confined to the realms of science fiction or theory. As recently as 2022, a cyberattack on the network of a submarine communications cables operator was thwarted by the US Department of Homeland Security Investigations.[20] It was reported to have been from an international hacking group, the intentions of which were unclear. Further, the attackers were based overseas and help from multiple agencies of different States was required to make arrests.[21]

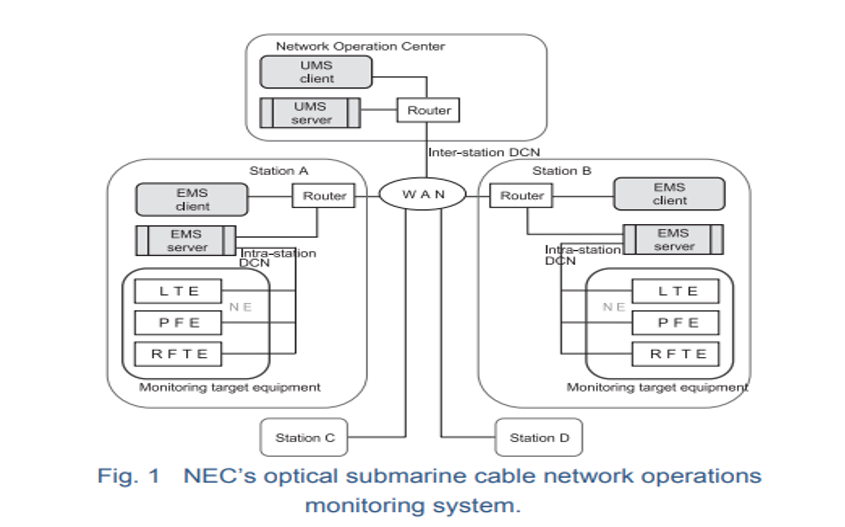

The following image is an example of the NMS deployed by the NEC (a Japanese submarine-cable manufacturer). It deploys an individual Element Management System (EMS) at each individual landing station, which is then connected to a Unified Management System (UMS) at a Network Operation Centre.[22]

Source: Nomura Kenichi et al, “Optical Submarine Cable Network Monitoring Equipment”

Data Disruption vs Data Tapping

Accessing the NMS can enable the accessor to undertake two activities. First, it may choose to disrupt the flow of data to cease communications. The second, which is more subtle and covert, is the interception of data flowing through the landing stations. So, while data continues to flow, the accessor is now privy to its contents. While data surveillance is not a new phenomenon, it has thus far focused upon the physical tapping of the cable or cable landing station with intercept probes capturing the light being sent across the cable.[23] This installation of probes could either be done covertly, or with permission from the host State/company as permitted/mandated by law.[24] Remote access may permit copying of data especially by remotely situated, non-friendly States and state-sponsored non-State actors who do not have the access required to place physical taps. This is a point of intersection between the security of the logic layer and data security.

Vulnerability of the Information Layer

Informational security may be breached at two points of the system, viz., either at the logical layer through the NMS, or through the physical layer either on the cable itself or at the Cable Landing Station.

Interception and accessing data flowing through the CLS has, in fact, received legal sanction. States can legally access data from the CLS on their home soil. Operation TEMPURA by the UK Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ), which involved mass surveillance by interception of submarine cables and cable landing stations in the UK, was justified under the 2000 Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act that allowed tapping of defined targets, including broad categories of material, as long as one end of the communication was from abroad.[25] This Act has since been replaced by the Investigatory Powers Act 2016 (IPA) for the interception (including equipment interference), acquisition, and retention of communications data. This 2016 Act creates an offence of “unlawful interception” of public and private telecommunication systems if carried out “in the UK” without “lawful authority” (s3 IPA). The two exceptions carved out are (a) if the interception is done with the express or implied consent of a person with a right to control the operation or use of the system, and (b) with a targeted or bulk interception warrant issued under the IPA.

Section 136 of the IPA, which governs bulk interception warrants, defines them as those that intercept “overseas-related communication” (sent or received by individuals who are outside the British Islands) and authorises or requires the person to whom it is addressed to secure the interception, examination, and disclosure of intercepted content (emphasis added). A submarine communication cable system falls neatly within this legal framework and enables the UK to intercept the communications data flowing through or stored within the system, either through operator consent or mandatorily through the issuance of bulk interception warrants.

This power is, however, regulated by IPA 2016 itself, which requires a host of conditions to be fulfilled before such a warrant can be issued. Section 138 of the IPA requires the Secretary of State (a high-ranking public official) to issue such warrant on application by or on behalf of a head of an intelligence service (initial access limited) for interception of overseas-related information if it is necessary in interests of national security, preventing or detecting serious crime, or interests of economic well-being of the UK (emphases added). This warrant then needs to be approved by a Judicial Commissioner who will gauge whether the requirements of necessity and proportionality have been met. Therefore, while bulk interception is permissible, a system of checks and balances has been created, at least theoretically, despite the use of the catch-all phrase of ‘national security.’ In practice, of course, it appears unlikely for a Judicial Commissioner not to approve such a warrant pertaining to overseas-based communications, especially on grounds of national security. Nevertheless, the Act may preclude a routine execution of such warrants, since the aim is to protect the privacy of British nationals.

While British law is well-structured with adequate checks and balances, other pieces of jurisdiction, such as those of the People’s Republic of China, do not have such mechanisms in place. The infamous National Intelligence Law of the PRC requires Chinese citizens and organisations to cooperate with state intelligence work.[26] The terms cooperation and intelligence work are vague and could compel Chinese companies to provide a whole range of data and information. This law is buttressed with other national and cybersecurity legislation, for example the Counterespionage Law and the Cybersecurity Review Measures, which provide the basis for defensive and protective action.[27] Thus, any Chinese cable operator or cable landing station owner, if so directed, would have to gather, and share with the Chinese government, any and all data that flows through that cable landing station, which may be China-bound or merely transiting China.

The US, on the other hand, adopts a contractual mechanism for data surveillance and protection.[28] A practice, which began as far back as 2003, involves signing of a Network Security Agreement which, though framed in terms purporting to protect telecommunication networks from foreign spying, also enables US government agencies to seek access to the data flowing through these networks. Licensing requirements are used as leverage to set up a corporate cell within the company, consisting of American nationals with government clearances, who facilitate consent for surveillance.[29] Moreover, even the Network Operations Centre is contractually mandated to be located in the US, thereby subjecting it to US law and enforcement.[30]

Naturally, the concentration of data servers will naturally lead to more cables and cable landing stations being stationed in that territory and will bring with it the application of that State’s domestic law. Consequently, the promotion of local data servers limit the data that flows outside the country, which is subject to foreign surveillance.

India, too, has a mechanism in place to direct interception, monitoring, and decryption of information. The mechanism is regulated by the Indian Telegraph Act 1885 and the Information Technology Act 2000. The Indian Telegraph Act, applicable to any appliance capable of transmission or reception of signals by electro-magnetic emissions (this would bring a CLS within its ambit) gives the Central or State governments power to order the interception of messages (s5 Indian Telegraph Act) or to disclose transmission to the Government. This order can be made if it is deemed necessary or expedient to do so in the interest of the sovereignty and integrity of India, the security of the State, friendly relations with foreign States, public order, or preventing incitement to the commissioning of an offence. s69 of the Information Technology Act, which retains the bulk of the provisions of the Indian Telegraph Act, additionally includes “monitoring” of any information “generated, transmitted, received or stored in any computer resource”. Further, the provision also requires the subscriber, intermediary or any person in-charge of the computer-resource to extend facilities and technical assistance to provide or secure access to the computer resource, or intercept, monitor, decrypt, or provide information stored in the computer resource, the failure of which is a criminal offence. This is not a blanket power and is limited by the Information Technology (Procedures and Safeguards for Interception, Monitoring or Decryption of Information) Rules, 2009, which require a Secretary-level government official or senior police officer to authorise such interception. Hence, such directions shall be made at high levels of government authority. It is to be seen how these provisions will be modified with the introduction of the new Telecommunication Act and the Digital India Act. Care must be exercised to ensure that the provisions of these two acts do not conflict when applied to the submarine cable system which straddles telecommunication and cybersecurity.

Hence, it is very likely that data flowing in a submarine cable could be compromised. While these are mechanisms for lawfully authorising access to the data, such processes are restricted (largely) to companies/cable landing stations in the host State. However, unauthorised access to the NMS may allow both State and non-State actors to gain access to data flowing through the NMS between two different countries.

Another significant threat to data security is the inclusion of remote surveillance equipment in the cable by the cable manufacturer.[31] Hence, the use of foreign cable manufacturers, too, poses an inherent threat to the system. It is for this reason that the US has been using diplomatic tools to ensure that Chinese cable-manufacturers do not win consortium contracts to manufacture and lay cables, including those that do not necessarily land either in the US or China. For instance, the US State Department helped SubCom secure a deal for the SEA-ME-WE 6 Cable to connect Singapore to France by offering training grants to consortium telcos and threatening to impose sanctions on cable system operations.[32] In addition to the objective of restricting Chinese advances in emerging technologies, the US State Department seeks to counter the threat of HMN Tech placing surveillance equipment in the cable system that had Microsoft as a consortium member, and US tech companies as the biggest (likely) capacity buyers. China, similarly, has delayed granting a license to Japanese manufacturer NEC for laying a cable to pass through the South China Sea and land in Hong Kong and mainland China.[33] Just as cable manufacturers may insert surveillance equipment into the cable, it is foreseeable that NMS service providers may introduce backdoor entries into the system, which could make them accessible in times of need.[34]

Such methods may be preferred to traditional espionage or miliary activities due to low cost, difficulty in attribution of source, minimal escalation, asymmetric impact, and an underdeveloped legal framework to guide responses.[35] China is thought to be allocating very significant resources to computer network operations (CNO), including computer network attacks (CNA), computer network exploitation (CNE), and computer network defence (CND).[36] It is very probable that this ever-increasing threat will play a decisive role in any future conflict. Sabotage mechanisms are especially effective prior to kinetic attacks, as they tend to confuse and weaken the target.[37] Requisite focus must, therefore, be given to the logical and data layers as well.

PROTECTIVE MECHANISMS PER LAYER

Holistic security of a cable system can be ensured only if its constituent layers are effectively addressed. Measures will need to include a mix of operational and legal/regulatory mechanisms.

Physical Layer

Protection of the physical layer includes offshore patrolling, creation of cable protection zones, Faraday-caging the CLS, and adequate physical security measures for cable landing stations. States are increasingly adopting dedicated ships to their fleet for the protection of undersea infrastructure. For instance, the RFA Proteus, operated by the Royal Fleet Auxiliary of the United Kingdom, has been inducted specifically to protect undersea cables and infrastructure through underwater surveillance.[38] This mechanism is a response to the new front of ‘seabed warfare’ and designed primarily for the prevention of intentional sabotage.[39] There is also scope for regional collaboration in the form of joint patrols and exercises for undersea infrastructure protection. Cable Protection Zones, a concept adopted through Australian legislation, protect against accidental harm caused due to trawling and anchoring and also form the basis for legal action against persons charged with damaging cables in Australian waters. Ashore, protection of CLS is of paramount importance due its nature as a node in the system as well as relative ease in its access.

Logical Layer

Threats to the logical layer of the system seldom receive the attention that is necessary, given that the growing cyber capabilities of both State and non-State actors could enable them to hold an entire infrastructure system hostage. Currently, logical-layer security has been left almost entirely to the private sector. A glaring example of the neglect of security for this layer may be seen in the recent French Seabed Warfare Strategy, which while including within its ambit the protection of submarine communication cables, limits its focus to the protection of the physical and informational layer, with no mention at all of protection to the logical layer. Such neglect constitutes the Achille’s Heel of cable protection measures. There is, however, a growing recognition of this threat and the “Enhanced EU Maritime Security Strategy for Evolving Maritime Threats” is a welcome initiative that acknowledges the increased likelihood of hybrid and cyber means to target maritime infrastructure such as undersea cables and pipelines.[40]

It is important for the State to establish minimum standards for equipment, software, and best network-security practices. Owners of CLS must, as a prerequisite for obtaining a cable license, demonstrate that adequate security practices are being adhered-to, with periodic review mechanisms to ensure that these security practices remain up to date with concomitant advances in cyber capabilities. These requirements must be established by law or, at the very least, by regulations.

Indian practice currently involves using the contractual mechanism by incorporating within the license agreement concluded between the International Long-Distance Operator (cable or CLS operator) and the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India, obligations to ensure network security.[41] The license terms require the licensee to:

- have a well outlined organisational policy on security and security management of their networks, for which they are totally responsible.

- perform network forensics, network hardening, network penetration test, risk assessment, actions.

- conduct a third-party audit to core equipment such as routers, switches, firewalls, IDS, IPS, VOIP and software associated with all the Telecom operations and services.

- monitor all intrusions and frauds, report the same to TRAI and/or to CERT-IN

- have a well-articulated policy for disaster recovery.

- ‘endeavour’ to create a forum such as a “Telecom Security Council of India” on a voluntary basis with part government funding to “increase security assurance levels and share common issues.”

- Enable the licensee and TRAI/DoT to carry out inspections of the vendor/supplier. The inspection can cover the hardware, software, design, development, manufacturing facility, supply chain, and all software to a security/threat check at the time of procurement of equipment, and at least one more time in year of procurement, and every two years thereafter at the time of discretion of the provider.

Thus, there exists a contractual obligation on the ILD license holder to take into account network security by testing the network, the equipment, and enabling the license holder and TRAI to inspect even the vendors involved. Penalties for any breach in the equipment will be imposed on the licensee thus making the licensee wholly responsible for network and equipment integrity.

However, beyond the contractual mechanism, the existence of minimum security-standards introduced through legislation/delegated legislation tailored to NMS remains essential, considering their criticality to the entire system. ‘Generalised’ obligations to maintain network security may well afford protection against ordinary ransomware or malicious actors but not against State or State-sponsored non-State actors. An example is the requirement for the NMS to use secure protocols for data transfer. Given multiple private players in this industry, statutory obligations would ensure that baseline standards are adhered-to by all industry players. As things stand, statutory obligations tend to have better compliance in India as opposed to purely contractual obligations (not least because of the ‘standard-form’ nature of government contracts). Contractual obligations enable ‘reaction’ by pursuing contractual damages when an incident occurs rather than ensuring ‘prevention’ and are enforceable only by and against contracting parties, while other stakeholders and actors fall outside its scope. The ‘standard form’ contract seeks to exact a penalty from the licensee for any discovery in breach after installation. Moreover, the principles upon which contract law in India is founded, permit liquidated damages to be awarded but do not permit the award of penalties in the contract.[42] Regulations are likely to overcome such infirmities.

Furthermore, the Telecom Bill 2022, requires registration of telecommunication infrastructure as opposed to a license needed for telecommunication services and telecommunication networks. While it is unclear as to whether a CLS is a ‘telecommunication infrastructure’ or ‘telecommunication network’ (not included in either definition), it is nevertheless prudent for the Central Government to utilise the powers provided in s23 of the Telecom Bill to establish standards of the NMS that may be acquired. The powers under s23 are wide-ranging and cover telecommunication equipment, services, network, infrastructure, and even the manufacturers, importers, and distributors of telecommunication equipment. Best practices too, should be incorporated within these regulations.

It is important that these practices are adhered to in spirit and not merely given lip-service. Thus, the conduct of best practices must be communicated to TRAI even before there is any intrusion into the system.

In this regard, Chinese State practice merits mention. The Critical Information Infrastructure Security Protection Regulations[43] explicitly includes within its scope network infrastructure in public telecommunications (Article 2) and mandates the State to deal with cybersecurity risks and threats from attacks, intrusions, interference, and destruction, emerging from inside and outside PRC (Article 5). Operators are mandated to adopt requirements of national standards, respond to, and prevent cyberattacks to critical information infrastructure (Article 6). They are required to conduct cybersecurity survey and risk assessments at least once a year (Article 17) and “shall prioritise the purchasing of secure and reliable network products and services which shall undergo a security review according to national cybersecurity regulations” (Article 19). Guidelines for network security review measures, too, have been adopted.[44] Information infrastructure operators are required to predict the risks to national security emanating from network products and services and submit these to a network security review if they affect or may affect national security (Article 5 of Measures). Thus: Article 10: Cybersecurity review focuses on assessing the following national security risk factors of relevant objects or situations:

(1) The risk of key information infrastructure being illegally controlled, interfered with, or destroyed after the use of products and services;

(2) The disruption of product and service supply to the business continuity of critical information infrastructure;

(3) The safety, openness, transparency, and diversity of sources of products and services, the reliability of supply channels, and the risk of supply interruption due to political, diplomatic, trade and other factors;

(4) Product and service providers’ compliance with Chinese laws, administrative regulations, and departmental rules;

(5) Risks of core data, important data, or a large amount of personal information being stolen, leaked, damaged, illegally used, or illegally exported;

(6) There are risks of key information infrastructure, core data, important data, or a large amount of personal information being influenced, controlled, or maliciously used by foreign governments, as well as network information security risks;

(7) Other factors that may endanger the security of critical information infrastructure, network security, and data security.

As may be observed, the Chinese model covers both the logical layer and the informational layer at their intersection, providing more holistic security which is linked to the broader data and cyber security architecture within China.

The American system, on the other hand, requires only federal agencies to implement security controls under the Federal Information Security Modernisation Act 2002 and adopts a voluntary approach for private players under the Cybersecurity Information Sharing Act 2015. It allows companies to share cyber threats information with the Department of Homeland Security which is responsible for protecting US critical infrastructure.

Informational Security

Informational security in the context of submarine cable systems needs to be ensured at two points, viz., at the physical level and the logical one. Resilience in the NMS, supported by periodic monitoring, would safeguard both the logical layer and the associated flow of information. The threat to informational security from the physical layer predominantly emanates from the involvement of foreign service providers either in the manufacture, laying, or repair stage. Additionally, even the use of cables owned/operated by foreign firms presents a threat to data security, which, of course, has prompted States to lay their own cables.[45]

The United States, for example, has sought to counter this threat in two ways. The first involves scrutiny of foreign participation in the US telecom sector, while the second is seeks to restrict the growth of foreign cable manufacturers by preventing the sale of cable technology and access to business. Vide an Executive Order, the erstwhile-unofficial inter-agency ‘Team Telecom’, which played a key role in the negotiations of the Network Security Agreements, was officially established as the Committee for the Assessment of Foreign Participation in the United States Telecommunications Services Sector (Committee), to advise the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) on ‘public interest’ review of foreign participation in the telecom sector.[46] In addition to the requirements in the Cable Landing License Act 1921, any new application which involves 10% or greater direct or indirect ownership may be sent for review to the Committee, which may advise the FCC to either reject the application, accept it, or grant approval contingent to compliance with mitigation agreements negotiated by the Committee. The Committee generally asks questions that include how call data and other information will be stored, how data will be secured, and who will have access to the applicant’s network and data.[47] Provision of international telecommunication services to and from the United States, and permission to land and operate an international undersea cable that touches a US territory are applications that fall within the scope of Committee review.[48] It is important to highlight that the term ‘public interest’ has not been defined and the scope of the review would include conciliation with not only national security and law enforcement but also foreign or trade policy of the US and is therefore, wide in scope. The applicant is any entity which either owns or operates a cable landing station in the US or own or control 5% or greater interest in the cable system.[49] The foreign ownership is gauged of the applicant(s) and not necessarily of the cable manufacturer or any other service provider. Therefore, the threat of surveillance would remain even if the applicant were a US national. However, the FCC retains discretion to determine which applications are sent for review and may leverage this power to push applicants to engage US or allied service providers. Further, each committee review will include a threat analysis by the Director of National Intelligence who may also be required to report on compliance and enforcement of mitigation measures imposed. Such scrutiny has resulted in Chinese players being denied access to the telecom sector in the United States due to high threat perception.[50] This restriction is primarily for the US market. For global markets and cables not landing in US territory, diplomatic pressure and the carrot-and-stick strategy has been used to deny market access to Chinese players and ensure that contracts to manufacture and lay cables are placed with US companies, giving the United States greater control over the global flow of information.[51]

This brings to fore the geopolitical interests in controlling global communications accentuated by the lack of players in this industry. SubCom (United States), Alcatel (France), and NEC (Japan) are the three major players with HMN Tech (China- Formerly a subsidiary of Huawei) an emerging player. In order to prevent further growth of private players especially from China, the US House of Representatives have passed the Undersea Cable Control Bill[52] to “require the development of a strategy to eliminate the availability to foreign adversaries of goods and technologies capable of supporting undersea cables, and for other purposes.” It seeks to place a statutory obligation on the President of the United States to identify:

- goods and technology capable of supporting construction, maintenance, or operation of undersea cable project,

- unilateral and multilateral export controls and licensing policy for such goods and technology

- existing share of global market of US and allies

- existing market share of adversaries

- seek unified export controls and licensing polices to eliminate the availability of such goods and technology to foreign adversaries.

The term ‘adversary’ has been taken to be that defined in the Secure and Trusted Communications Networks Act 2019 and, as such, includes the People’s Republic of China. However, given the shifting dynamics of international relations, the terms ‘allies’ and ‘adversaries’ acquire a fluid and dynamic definition creating a potential threat to both allies and adversaries alike. Therefore, the promotion of domestic and regional capacity for cable construction, maintenance, and operation acquires even greater significance.

The practice within India has evolved to protect informational security at its intersection with the physical layer of the cable system. The Cabinet Committee on Security recently approved the National Security Directive on Telecommunication Sector, which came into effect after the launch of ‘The Trusted Telecom Portal’ in 2021.[53] It is only ‘Trusted Products’ procured from ‘Trusted Sources’ listed on the portal that may be connected to the network.[54] This list seeks to ensure that compromised hardware is not connected to the network. The National Cyber Security Coordinator is the ‘designated authority’ to determine the inclusion of a particular source or product within the list. The process allows for non-India-registered Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs) to be included on application by either the telecom provider or via an India-registered subsidiary.[55]

India, therefore, adopts an exclusionary approach to foreign participation whereby only a select few are allowed to supply equipment. This, combined with ILD licenses only being available to Indian telecom providers, makes the telecom sector less competitive but, since the introduction of the National Security Directive, has a lower risk of foreign surveillance through hardware equipment.

This process needs to be reconciled with the power that the Central Government wields under the Telecom Bill 2022 to establish standards. These processes need to be linked and must be used to establish best practices even beyond minimum standards. Explicitly identifying what the best practices are in the acquisition of trusted products and in terms of attaining recognition of being a trusted source will improve ease of doing business, and is more likely to improve compliance with the best practices.

Recommendations

Essentially, any holistic and comprehensive plan for the protection of submarine communication cables must account for all its layers. While the Indian regulatory system is evolving to address the threats that may arise in each layer, with progress being made in the Telecom Bill 2022, it is still fragmented. TRAI’s recommendation that a chapter on ‘cable landing stations’ and ‘submarine cables’ be included in the Telecom Bill 2022 is a step in the right direction. Such a chapter must explicitly identify the status of the cable landing station and its associated software, and lay emphasis on the physical, logical, and informational security of the cables. The power to establish standards must include best practices for network security and introduce a mandatory periodic reporting requirement through regulation and not merely as a contractual obligation. Further, India must promote local cable manufacturing capabilities and promote local data centres to better safeguard our systems. Further, there must be a reconciliation in the mandate of the Central government rules/standards, the Trusted Telecom portal by the National Cybersecurity Coordinator, and the National Critical Information Infrastructure Protection Centre as and when it is notified. Reconciliation must also be made between the cyber security provisions in the Telecom Bill to those in the proposed Digital India Act.

India is definitely moving in the right direction with respect to submarine cable protection and the introduction of comprehensive and focused legislation on submarine cables will certainly make India a pioneer in cable protection.

*****

About the Author:

Soham Agarwal, a Delhi-based lawyer holds a Bachelor of Law (Honours) degree from the University of Nottingham, UK. He is currently an Associate Fellow with the Public International Maritime Law Cluster of the National Maritime Foundation, New Delhi. His research areas include the seabed, maritime infrastructures and seabed warfare. He may be contacted at law10.nmf@gmail.com

[1] Telecom Regulatory Authority of India, Recommendations on Licensing Framework and Regulatory Mechanism for Submarine Cable Landing in India, New Delhi, June 2023. https://www.trai.gov.in/sites/default/files/Recommendation_19062023.pdf

[2] Ibid p 68

[3] David Clark, “Characterizing Cyberspace: Past, Present, and Future” ECIR Working Paper, 12 March 2010 https://ecir.mit.edu/sites/default/files/documents/%5BClark%5D%20Characterizing%20Cyberspace-%20Past%2C%20Present%20and%20Future.pdf

[4] Congressional Research Service, Undersea Telecommunication Cables: Technology Overview and Issues for Congress, Jill C Gallagher. R47237, Washington DC: September 2022. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R47237 p 5

[5] Ibid

[6] Kaneko Tomoyuki, Chiba Yoshinori, Kunimi Kaneaki, Nakamura Tomotaka, “Power Feeding Equipment for Optical Submarine Cable Systems”, NEC Technical Journal, Vol 5, No. 1 (2010): 28-32 https://www.nec.com/en/global/techrep/journal/g10/n01/pdf/100107.pdf?nid=gihoEN017 1

[7] Inoue Takanori, Aida Ryuji, Yamaguchi Katsuji, “Enabling International Communications – Technologies for Capacity Increase and Reliability Improvement in Submarine Cable Networks” NEC Technical Journal – Special Issue on Solving Social Issues Through Business Activities 8, No. 1 (2013): 19-22 https://www.nec.com/en/global/techrep/journal/g13/n01/pdf/130104.pdf

[8] Doug Brake, “Submarine Cables: Critical Infrastructure for Global Communications,” Information Technology & Innovation Foundation, April 2019. https://www2.itif.org/2019-submarine-cables.pdf

[9] “Network Management System – NMS,” HMN Technologies, 2023 https://www.hmntechnologies.com/enDryPlants/37415.jhtml

[10] Open Cable Solution: System More Open, Networks More Flexible, HMN Tech, 2023 https://www.hmntechnologies.com/enjsrdA.jhtml;

This tech is also offered by NEC. See Nomura Kenichi, Takeda Takaaki, “Optical Submarine Cable Network Monitoring Equipment”, NEC Technical Journal 5, No. 1, (2010): 33-37 https://www.nec.com/en/global/techrep/journal/g10/n01/pdf/100108.pdf

[11] Justin Sherman, “Trend 2: Companies Using Remote Management Systems for Cable Networks.” Cyber Defense Across the Ocean Floor: The Geopolitics of Submarine Cable Security. Atlantic Council, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep35117.7

[12] The physical layer, its vulnerabilities, and legal and policy measures are elucidated in more detail in Soham Agarwal & VAdm Pradeep Chauhan, “Underwater Communication Cables: Vulnerabilities And Protective Measures Relevant To India” National Maritime Foundation, 2021 https://maritimeindia.org/underwater-communication-cables-vulnerabilities-and-protective-measures-relevant-to-india-part-1/

[13] Inoue Takanori et al, “Enabling International Communications,” 5.

[14] Ibid

[15] Michael Sechrist, “Vulnerabilities in Undersea Communications Cable Network Management Systems,” New Threats, Old Technology. Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Harvard Kennedy School (2012) https://www.belfercenter.org/sites/default/files/files/publication/sechrist-dp-2012-03-march-5-2012-final.pdf

[16] Ibid

[17] Justin Sherman, “Cyber-Security Across the Ocean Floor,” p19

[18] Ibid p18

[19] Nomura Kenichi et al, “Optical Submarine Cable Network Monitoring Equipment,” 5. and Michael Sechrist, “Vulnerabilities in Undersea Communications Cable Netwok”

[20] Peter Boylan, “Cyberattack on Hawaii undersea communications cable thwarted by Homeland Security” Star Advertiser, April 12, 2022. https://www.staradvertiser.com/2022/04/12/breaking-news/cyberattack-on-hawaii-undersea-communications-cable-thwarted-by-homeland-security/

[21] Ibid

[22] Nomura Kenichi et al, “Optical Submarine Cable Network Monitoring Equipment,” 5

[23] Olga Khazan, “The Creepy, Long-Standing Practice of Undersea Cable Tapping,” The Atlantic, July 2013. https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2013/07/the-creepy-long-standing-practice-of-undersea-cable-tapping/277855/

[24] Ibid

[25] Ewen MacAskill, Julian Borger, Nick Hopkins, Nick Davies, and James Ball, “GCHQ taps fibre-optic cables for secret access to world’s communications,” The Guardian, 21 June 2013. https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2013/jun/21/gchq-cables-secret-world-communications-nsa

[26] Anushka Saraswat, “Understanding the National Intelligence Law of China: Why India banned Tik Tok?”, Diplomatist, 5 September 2020. https://diplomatist.com/2020/09/05/understanding-the-national-intelligence-law-of-china-why-india-banned-tik-tok/

[27] Michael K Atkinson, Caroline E Brown, Evan Y Chuck, Kelsey Clinton, and Jeremy Iloulian, “China’s Revised Counterespionage Law and Recent Actions Highlight Challenges for U.S. Companies Operating in China”, Lexology, 10 May 2023. https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=629864e4-351e-4831-a98f-fa08cb2924fa

[28] Craig Timberg and Ellen Nakashima, “Agreements with private companies protect US access to cables’ data for surveillance”, The Washington Post, July 6 2013 https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/technology/agreements-with-private-companies-protect-us-access-to-cables-data-for-surveillance/2013/07/06/aa5d017a-df77-11e2-b2d4-ea6d8f477a01_story.html

[29] Ibid

[30] Ibid

[31] Joe Brock, “US and China wage war beneath the waves- over internet cables”, Reuters, March 24, 2023 https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/us-china-tech-cables/

[32] Ibid

[33] Ibid

[34] Lane Burdette, “Leveraging Submarine Cables for Political Gain: US Responses to Chinese Strategy” Journal of Public & International Affairs, (May 2021) https://jpia.princeton.edu/news/leveraging-submarine-cables-political-gain-us-responses-chinese-strategy

[35] US-China Economic and Security Review Commission, “2008 Annual Report to Congress”, Washington DC, (November 2008) https://www.uscc.gov/annual-report/2008-annual-report-congress

[36] Ibid

[37] Jon R Lindsay and Kello Lucas, “Correspondence: A Cyber Disagreement.” International Security 39 (2): 181–88.

[38] Ministry of Defence, United Kingdom, “New UK subsea protection ship arrives into Meseyside,” Press Release, 19 January 2023. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/new-uk-subsea-protection-ship-arrives-into-merseyside

[39] Louisa Brooke-Holland, “Seabed Warfare: Protecting the UK’s undersea infrastructure” House of Commons Library, 24 May 2023 https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/seabed-warfare-protecting-the-uks-undersea-infrastructure/

[40] High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, European Commisssion, An enhanced EU Maritime Security Strategy for evolving maritime threats. Brussels (March 2023) https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:9e3d4557-bf39-11ed-8912-01aa75ed71a1.0001.02/DOC_1&format=PDF

[41] Department of Telecommunications, Ministry of Communications and IT, Government of India, “Amendment to the International Long Distance Service License Agreement for security related concerns for expansion of Telecom Services in various zones of the country.” Letter No. 10-54/2010-CS.III (ILD), New Delhi (August 2010) https://dot.gov.in/sites/default/files/2-ILD_11.08.2010.pdf?download=1

[42] Karun Mehta and Shreyas Edupuganti, “Curious Case of Section 74 of the Indian Contract Act”, Mondaq, 10 June 2020. https://www.mondaq.com/india/contracts-and-commercial-law/950450/curious-case-of-section-74-of-the-indian-contract-act

[43] Rogier Creemers, Samm Sacks, Graham Webster, “Translation: Critical Information Infrastructure Security Protection Regulations,” Stanford Cyber Policy Center, (August 2021). https://digichina.stanford.edu/work/translation-critical-information-infrastructure-security-protection-regulations-effective-sept-1-2021/

[44] “Measures for Cybersecurity Review” (December 2021) http://www.cac.gov.cn/2022-01/04/c_1642894602182845.htm

[45] Robin Emmott, “Brazil, Europe plan undersea cable to skirt US spying”, Reuters, 24 February 2014 https://www.reuters.com/article/us-eu-brazil-idUSBREA1N0PL20140224

[46] Federal Communications Commission, Process Reform for Executive Branch Review of Certain FCC Applications and Petitions Involving Foreign Ownership, FCC 20-133, 01 October 2020 https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/FCC-20-133A1.pdf

[47] Andrew D Lipman and Nguyen T Vu, “Building a Submarine Cable: Navigating the Regulatory Waters of Licensing and Permitting” Submarine Telecoms Forum, March 2011. https://www.morganlewis.com/-/media/files/docs/archive/stf_56_6196pdf.pdf

[48] US Department of Justice, The Committee for the Assessment of Foreign Participation in the United States Telecommunications Services Sector – FAQs https://www.justice.gov/nsd/committee-assessment-foreign-participation-united-states-telecommunications-services-sector#2

[49] Emmott, “Brazil, Europe plan undersea cable to skirt US spying” Reuters, 24 February 2014

[50] Farhad Jalinous, Karalyn Mildorf, Keith Schomig, “Team Telecom Formalised into New Committee: Increased Scrutiny of Chinese Involvement in US Telecommunications Services Continues” White & Case, 15 April 2020 https://www.whitecase.com/insight-alert/team-telecom-formalized-new-committee-increased-scrutiny-chinese-involvement-us

[51] Joe Brock, “US and China wage war beneath the waves- over internet cables,” Reuters, March 24, 2023

[52] Undersea Cable Control Act, H.R. 1189 (February 24, 2023) https://mast.house.gov/_cache/files/f/2/f2428b4c-4d67-40cf-8103-16fb6c8c2b54/53191D5D3502F2288468E25DEB68F433.bills-118hr1189ih.pdf

[53] National Security Council Secretariat, Launch of the ‘Trusted Telecom Portal for implementation of the National Security Directive on Telecommunication Sector https://dot.gov.in/sites/default/files/Brief%20on%20launch%20of%20Trusted%20Telecom%20Portal-1.pdf?download=1

[54] Department of Telecommunications, Ministry of Communications, Government of India, Compliance to the amendment to license conditions on National Security Directive on the Telecommunication Sector (NSDTS)- Actions to be taken by Licensees, File No. 820-01/2006-LR(Vol-II)(Pt.3), 17 June 2021 https://dot.gov.in/sites/default/files/Compliance%20to%20the%20amendment%20to%20license%20conditions%20on%20National%20Security%20Directive%20on%20the%20Telecommunication%20Sector%20%28NSDTS%29-Actions%20to%20be%20taken%20by%20Licensees.pdf?download=1

[55] Director, Trusted Telecom Cell, National Security Council Secretariat, Trusted Telecom Portal: Policy regarding input of data pertaining to Non-India Registered OEMs, 06 July 2021 https://dot.gov.in/sites/default/files/Trusted%20Telecom%20Portal.pdf?download=1

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!