A historical climate deal was reached in Paris on 12 Dec 2015. The legally binding agreement which has been touted as differentiated, balanced, durable and ambitious aims to limit the increase in the global average temperature to “well below 2 degree C”, above pre-industrial levels while “pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 degree C”. But what if any, are the implications of the agreement for international shipping? And, how can the maritime sector contribute to mitigating global GHG emissions?

International Shipping and CO2 Emissions

If international shipping was a country it would be the seventh largest GHG emitter in the world, in the year 2014. However, international shipping which contributes to 2-3 per cent and the aviation sector which contributes to approximately 2 per cent of the global carbon emissions were omitted from national commitments under the 1997 Kyoto Protocol. For the shipping sector, ships have different port of origin, destination port, intermediate ports of call, flag state of the ship (country where the ship is registered) and there are other actors in the industry such as private owners and operators of ships which have registered offices in all countries. Hence these sectors were excluded due to the complexity of accounting and appropriating emissions to countries. Nevertheless, due to environmental concerns on growing emissions the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) and the International Maritime Organization (IMO) were mandated to frame and implement laws to control the emissions from these sectors.

Despite steps taken by the organizations, there was an 80 per cent increase in CO2 emissions from these sectors between 1990 and 2010, as compared to a growth of 40 per cent from other activities across the globe. Further, according to the third IMO GHG study, it is estimated that the GHG emissions from international shipping are projected to grow to 6-14 per cent by 2050, an increase of 50-250 per cent from the business as usual (BAU) scenario due to increase in demand for seaborne transportation.

At the start of the negotiations the draft text of the Paris agreement had an explicit paragraph to control emissions from aviation and international shipping. However, during the course of the negotiations, the optional paragraph was omitted and these sectors are not included in the current climate deal. Therefore the responsibility to control GHG emissions from the shipping sector continues to rest with the IMO and there would be no national effort to regulate emissions from international shipping.

IMO’s Leadership Role

While the nature of activities and the non-homogeneity of the actors was an impediment in including international shipping in any country based GHG accounting framework, the sector, under the guidance of the IMO was able to successfully negotiate and adopt a model for controlling emissions. Three key agreements have been evolved by the IMO since 2010 under a sectoral framework, and these will continue to be implemented by the Marine Environment Protection Committee (MEPC) in a phased manner. These are:

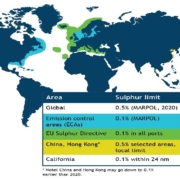

- Adoption of NOx Emission Standards for engines

- Reduction in sulfur content of fuel to contain SOx emissions

- Mandatory mechanisms aimed at reducing GHG emissions from ships such as Energy Efficiency Design Index (EEDI) and implementation of Ship Energy Efficiency Management Plan (SEEMP)

Not undermining the efforts of the IMO to regulate emissions from international shipping within the overarching framework supported by UNFCCC, much more still remains to be done. An overall cap on emissions was resisted by the IMO in the run up to the Paris meeting on the plea that it would restrict the profitability of shipping and would compromise on the industry’s ability to meet the growing demand of the world’s economy. However, the IMO expressed its solidarity with the global goal and has vowed to continue efforts to curb emissions from the sector.

An overall CO2 emissions cap for the sector has to be implemented equally across all countries for reductions of aggregate GHG emissions. Such an initiative has to be global and flag neutral and can be best delivered and implemented under the guidance and leadership of the IMO. Considering that the shipping sector continues to be ‘a servant of the world economy’ and that there are no overall caps which have been agreed in the Paris climate deal, the IMO is doing a decent job of driving the shipping industry on the path of lower CO2 emission intensity. The sectoral model which is applicable to all countries has triggered the growth of clean shipping and has the potential to reduce emissions of CO2 per tonne-km by 50 per cent by 2050. While an absolute cap may not be feasible as it is incident on the quantum of world trade, deeper emission intensity cuts which are in the range of 80-90 per cent have been suggested by 2050 if a 2 degree centigrade goal has to be met. An aggressive approach to meet this goal would also require that emissions from international shipping have to peak by 2020 and need to fall thereafter at a drastic pace. A CO2 neutral shipping industry by its own would be expensive to deliver and hence IMO must work towards offsetting these emissions by investing in carbon sinks in other sectors. Alternate options and other measures to reduce emissions would be discussed in the forthcoming 69th session of the MEPC meeting in April 2016.

Conclusion

While the global climate deal can be considered as a diplomatic success, it has left the maritime sector out of its ambit. This implies that the international shipping industry led by the IMO needs to demonstrate continued leadership for evolving binding agreements and for adopting targets which are consistent with the goal 1.5-2 degree C rise. The IMO is in a position to deliver a win-win arrangement as it can guide the sector to regulate itself while contributing to the global goal of attaining carbon neutrality. It can do this at a pace which is technologically feasible while maximizing profits and contributing to the growth of the world economy.

********************************

About the Author:

Kapil Narula is a Research Fellow, National Maritime Foundation, New Delhi. The views expressed are his own and do not reflect the official policy or position of the NMF, the Indian Navy or the Government of India. He can be reached at kapilnarula@yahoo.com

Image Credits: gCaptain

Image Credits: gCaptain cambiaso risso group

cambiaso risso group

Image Credit - International Register of Shipping

Image Credit - International Register of Shipping

Image Credits: Deltamarin Ltd

Image Credits: Deltamarin Ltd  Image Credit- United Nations Development Programme

Image Credit- United Nations Development Programme  Image Credits: The Brookings Institution

Image Credits: The Brookings Institution Image Credits: Allianz Global Corporate & Specialty

Image Credits: Allianz Global Corporate & Specialty

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!