The U.S. President Barack Obama made his maiden trip to Vietnam towards the end of his term in office in May 2016. The visit was to strengthen U.S.-Vietnam relations, as follow-on to the process of rapprochement between the two states, which began after the end of Cold War. Among the significant outcomes of the visit was lifting of the U.S. ban on sale of lethal weapons to Vietnam. A number of collaborative agreements were signed by both countries and a joint statement reaffirmed their obligations to observe the UN Charter and a commitment to respect “international law, their respective political systems, independence, sovereignty, and territorial integrity”. Further, both sides announced their commitment to enhance security in the maritime domain under the Maritime Security Initiative (MSI).

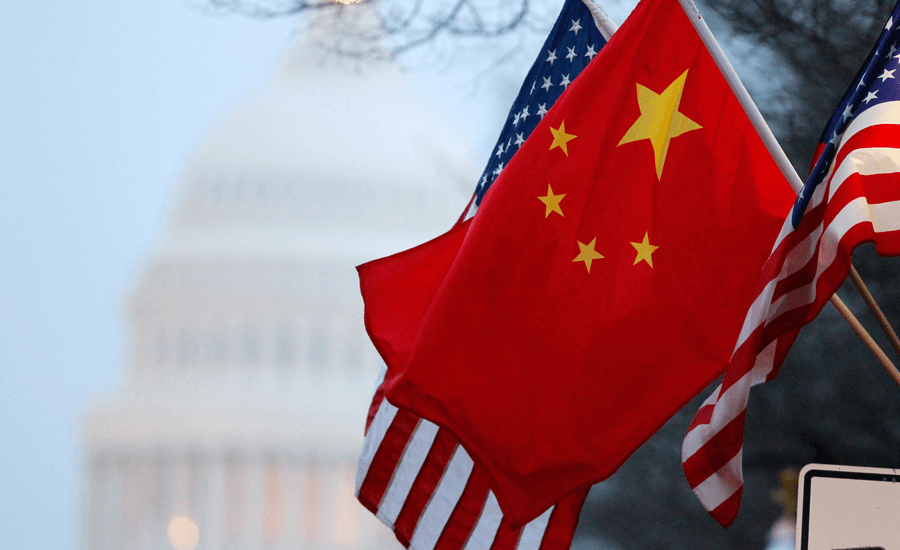

China’s growing assertiveness in the South China Sea (SCS) is a major concern for the Asia-Pacific countries and President Obama’s visit has generated many debates in the strategic circles for its implications on Sino-Vietnam relations. Though the visit was ostensibly aimed at normalization of relations with Vietnam, the ‘China containment’ angle can hardly be ignored.

China appears to be worried about the growing U.S.-Vietnam partnership and it has thus stepped up efforts to cooperate with Vietnam and improve bilateral relations. While Hanoi was under media glare following the visit of President Obama, another significant meeting was underway between the Vice Foreign Ministers of China and Vietnam to discuss the possibilities of cooperation. The above development raises an important question: Is it an indicator of the success of Vietnam’s ‘China strategy’? If so, does it have a takeaway for India?

It is pertinent to note that the Vietnam-U.S. rapprochement has culminated with several positive outcomes. Since 2015, China and Vietnam have been trying to strengthen Comprehensive Strategic Cooperative Partnership, and a joint communiqué was issued during President Xi Jinping’s visit to Vietnam, agreeing to enhance practical maritime cooperation and promote working groups for consultation on maritime joint development. The two countries agreed to manage the existing tensions in the SCS, and vowed to implement the Declaration on the conduct of parties in the SCS (DOC) for peaceful and durable solution of disputes as also undertake the signing of a full Code of Conduct (COC).

Towards Normalization

Asymmetry of power and history of conflict characterize Vietnam’s relations, with both China and the U.S. By the end of Cold-War, Vietnam had begun to normalize relations with both China and the U.S., and has made major strides since then. Given the ideological affinity, Sino-Vietnam relations have been traditionally marked by close camaraderie binding socialist countries, and they have been “credible friends and sincere partners” who established diplomatic engagement nearly six decades ago. Notwithstanding this, Sino-Vietnam relations have been unequal and non-reciprocal, whereas the U.S. rapprochement is a “step by step” approach; reciprocal, positive and mutually beneficial. In contrast, apart from the post-Cold War imperatives to normalize US-Vietnam relations, the bilateral ties are influenced by external factors, of which the strategic and economic partnership with the U.S. are major determinants.

Vietnam’s Hedging Strategy

Vietnam has historically adopted a hedging strategy against China which characterizes a relationship between a small and a big power. This indicates that while collaborating with China to attain domestic political and economic gains, Vietnam also attempted to build extensive foreign relations with extra regional powers.

In the light of growing U.S.-Vietnam ties, cooperative and competitive outcomes vis-à-vis the U.S. and China emerge. Cooperative outcomes are derived when Vietnam capitalizes on economic and strategic assistance provided by the U.S., whereas competitive outcomes emerge from Vietnam’s relations vis-à-vis China in the context of competitive interests in the SCS. Concerned about China’s expansion, Vietnam engages in external balancing with the U.S. with favorable outcomes such as maritime security capability building and strengthening of maritime infrastructure through the MSI. This leads to shifts in the hedging strategy practiced by Vietnam against China, and further complicates the existing policy options available for it to uphold regional stability.

Standing at an inflection point where Vietnam must make a trade-off between the MSI of the U.S. and the MSR of China, within an overarching strategic context of the U.S. rebalance to Asia, Vietnam faces a dilemma in its policy formulations. The U.S. security assistance to Vietnam in the backdrop of SCS disputes is bound to create an unfavourable response in China, and stand in the way of harmonious Sino-Vietnam relations. The dilemma is to strike a balance between strategic objectives of maintaining favourable relations with China without destabilizing or derailing cooperative outcomes in the background of growing American strategic assistance. Vietnam is also reaching out for military assistance aimed at balancing China, which is perceived as an additional strand of its hedging strategy.

Vietnam can draw lessons from India’s experience of handling similar dilemma. India professes strategic autonomy, but also engages in strategic partnership with the U.S. This, along with the economic interdependence with China, creates a dilemma for India. However, there is a difference. Since both China and India are major regional powers, Sino-Indian relations are far more competitive than the Sino-Vietnam relations. Therefore, India’s approach to the U.S. and China is one of ‘balancing’ rather than ‘hedging’. India’s relations with Vietnam may be among the ‘tools’ of such ‘balancing’. Stronger ties with Vietnam result in greater advantage for Indian and the U.S., since it acts as leverage against the growing Chinese assertiveness. This also accrues a major dividend for Hanoi since it offsets Sino-Vietnam strategic asymmetry.

Given the ongoing disputes in the SCS which evade a clear resolution, and the U.S.’s greater visibility in the region, it remains to be seen whether Vietnam would adopt a balancing strategy against China or continue its hedging strategy. It is also difficult for Vietnam to assume an accommodating posture or bandwagon with China, as it has proved ineffective in the past. This results in dilemma in policy formulations.

The lack of an immediate threat from the American side, besides the US willingness and potential to counter China’s growing assertiveness in the SCS are factors that strengthen US-Vietnam ties. Will it lead to strengthening or breakdown of cooperative mechanisms between China and Vietnam is another moot issue. Vietnam is also careful not to antagonize China as it may jeopardize the development of a legallybinding China-ASEAN Code of Conduct (COC) for the SCS.

It is fair to argue that the current strategy of Vietnam underlines maritime cooperation with both China and the U.S. to utilize the benefits of the MSI and MSR. A more pragmatic policy and strategic vision to accommodate both Chinese and U.S. interest in the SCS issue as well as maintaining a balance in the relations between the two powers would be favorable for Vietnam.

********************************

About the Author:

Shereen Sherif is a Research Associate at the National Maritime Foundation (NMF), New Delhi. The views expressed are his own and do not reflect the official policy or position of the NMF, the Indian Navy, or the Government of India. She can be reached at shereensher@gmail.com

Image Credits: Council on Foreign Relations

Image Credits: Council on Foreign Relations Image Credits: Council on Foreign Relations

Image Credits: Council on Foreign Relations  Image Credits: Permanent Court of Arbitration

Image Credits: Permanent Court of Arbitration  Image Credits: DNA India

Image Credits: DNA India  Voice of america

Voice of america  Image Credits: The Quint

Image Credits: The Quint

Image Credits: Avenue Realty

Image Credits: Avenue Realty Image Credits: Vivekananda International Foundation

Image Credits: Vivekananda International Foundation

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!