Abstract

China has been trying assiduously, through a variety of means to assert greater control over the area encompassed by its so called ‘Nine-dash Line’ in the South China Sea. While it seeks to enforce its supposed rights in the area by deploying the Chinese Coast Guard (CCG) ships and maritime militia vessels for ‘grey zone’ warfare, the promulgation, in 2024, of China Coast Guard Regulation Number 3 (CCGR-3) legally empowers the CCG in execution of these aggressive tasks. However, certain ambiguous provisions related to geographical coverage, use of force methodology, arbitrary powers of detention and arrest of foreign ships accorded to the CCG, and omission of the status of warships with regard to their immunity from prosecution, have caused great concern to the global community. India’s interests could also be adversely impacted, since the Indian Navy ships which have been operating in the South China sea at an increased frequency, scale and intensity over the last decade, may also fall foul of this regulation. Therefore, all global stakeholders who value the ‘freedom, openness and security’ of the oceans as provided for under the existing rules-based order, must come together to challenge this Chinese propensity towards maritime expansion through promulgation of various domestic laws and regulations which do not conform to the customary international laws.

Keywords: China Coast Guard, CCGR-3, China Coas Guard Law-2021, Gray Zone warfare, Indian Navy, Indo-Pacific, Maritime Militia, Nine-Dash Lines, South China Sea

The South China Sea and the related contestation for various features and adjoining maritime zones therein, have found a lot of prominence in global media and strategic circles, of late. The last couple of years have witnessed particularly hectic jockeying for positions, influence, diplomatic and political brinkmanship by two major disputants — China and the Philippines —through various measures as per their respective capability and firmness of intent. The area has specifically witnessed aggressive employment of ‘grey zone’ tactics by the Chinese Coast Guard (CCG) ships and People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM) vessels to secure control over maximum maritime space around the disputed features, with the objective of eventually enforcing the Chinese jurisdiction over the entire area enclosed by the so called ‘nine/ten-dash lines’.

South China Sea as Core Chinese Interest

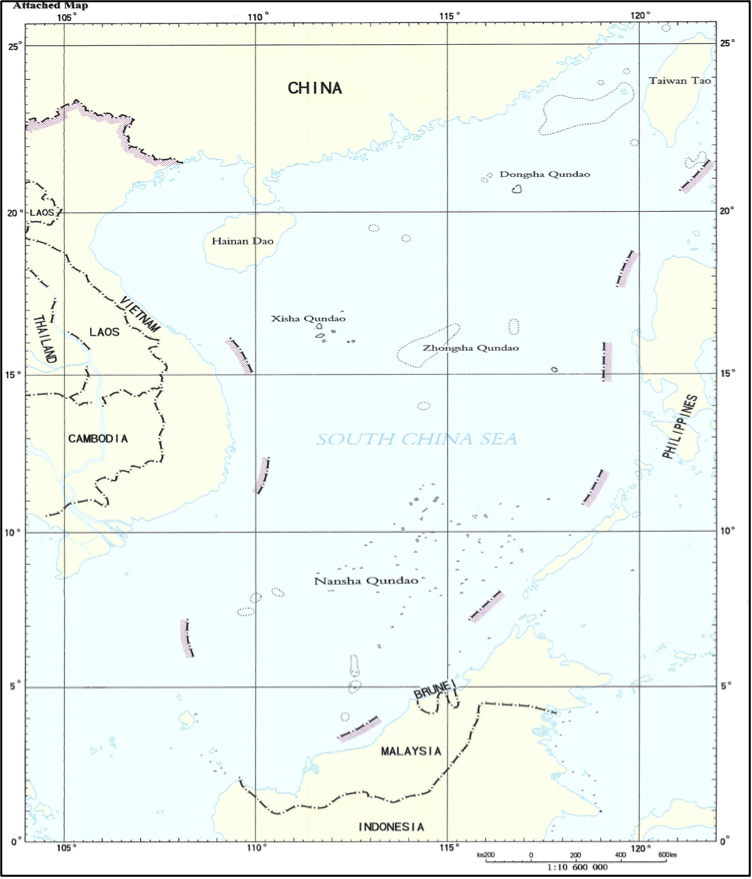

In this context, it would be instructive to recall that in March 2010, the then Chinese State Councillor, Dai Bingguo, conveyed to the visiting US Deputy Secretary of State, James Steinberg, that the South China Sea was part of the Chinese ‘core interests’ with regard to its sovereignty and territorial integrity.[1] This assertion followed an official note to the United Nations Commission on the Limits of Continental Shelf (UN CLCS) on May 7, 2009, wherein it was stated that China “enjoyed sovereign rights and jurisdiction over the islands in the South China Sea and the adjacent waters, as well as seabed and sub-soil thereof”.[2] A map of the region which was attached to this official note, showed the ‘nine-dash line’ marked therein. This map which formally illustrated the expansive limits of Chinese claim, is reproduced at Figure 1.

Figure 1: Map submitted to the UN by China on 07 May 2009, showing Nine-Dash Lines

Source: UN CLCS site

One must, however, remember that the South China Sea has always been of ‘core interest’ to China, but was not formally articulated to the world as such, until March of 2010. Various skirmishes that occurred between China and the other parties to the dispute in the region — be these with Vietnam in the 1970s or with the Philippines in the 1990s — have only reinforced this premise. A relatively overlooked fact is that internally, China has always regarded the South China Sea as part of its own territory and has ensured that this position permeates down to the lowest possible echelons of the Chinese governance and administration. This author has personally observed two specific instances of this persistent endeavour. The map of China printed inside the inflight magazine of ‘Air China’, the official Chinese civil-air carrier, depicted the entire South China Sea enclosed by dotted lines, and appended to the boundary of mainland Chinese. The same illustration was again observed in the elementary Chinese language textbook that the author happened to refer to, as part of his formal learning of the Chinese language in India.

Subsequent to taking an official position vis-à-vis ‘nine-dash lines’ with the May 2009 communication to the UN CLCS, Beijing has carried out several administrative reforms and enacted a number of laws and regulations to integrate various features and adjoining maritime areas lying within the so called ‘nine-dash line’ under its sovereignty and jurisdiction. China conferred the status of ‘prefecture’ to Sansha County on 21 June 2012 and tasked it with the administration of the Paracel and Spratly Island chains, in addition to that of Zhongsha Island (Macclesfield Bank).[3] In addition, the “Regulation for Management of Public Order for Coastal and Border Defense”, promulgated by the provincial Government of Hainan, took effect on 01 January 2013. This regulation authorised Hainan’s “Public Security Border Defense” units to board or detain foreign vessels, in case they were found to be “landing illegally on islands”, as also engaging in any one of five other misdemeanours in “waters under the administration of Hainan” — which presumably extended to sea areas well beyond the Chinese territorial waters of 12 nautical miles (NM).[4]

China Coast Guard Law (2021) and Regulation-3 (2024)

The CCG was brought under overall control of the Central Military Commission (CMC) in July of 2018 — as part of the wider reorganisation of the People’s Armed Police Force. The CCG was accorded additional (and quite wide-ranging) powers by promulgation of the Chinese Coast Guard Law in January 2021, so as to enable it to better “safeguard Chinese maritime rights and interests”.[5] That law caused serious concerns amongst the global community on account of its non-conformance with the provisions of the Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) 1982 and, more importantly, due to the lack of clarity over its geographical jurisdiction, its methodology in the use of force, and the linkage of the CCG’s role with that of “national security and defence”.[6]

Subsequently, CCG Regulation Number 3 (CCGR-3) was issued — on 15 May 2024 — which supposedly lays down detailed guidelines for implementation of that 2021 Law. The CCGR-3, spread over 16 chapters and encompassing 281 articles, came into force on 15 June 2024.[7] The regulation, by referring to the phrase “waters under the jurisdiction of our country” in Article 11, is as ambiguous on the specific geographical coverage as was the CCG Law of 2021 — and also uses the same terminology in its Article 25.[8] The most damning aspect of the CCGR-3 is contained in Article 105, which authorises the CCG to detain foreign ships that illegally enter “territorial waters” — a term not clearly defined either in the CCG Law-2021 or the CCGR-3. The fact that this detention — including that of personnel, too — can extend up to six months under the provisions of Article 257 of CCGR-3, makes it even more draconian.

Interestingly, while the applicability of CCGR-3 to the foreign ships has been mandated vide Article 105 as mentioned above, the regulation per-se makes no mention of foreign ‘State-owned vessels and warships’. This might well imply that such ‘State-owned vessels including warships’ also fall within the purview of the CCGR-3, and thus enjoy no special status or immunity. This glaring omission — whether deliberate or otherwise — leaves room for troubling interpretations by a concerned global community. The most obvious concern emanates from the fact that the United Nations “Convention on Jurisdictional Immunities of States and Their Property” of 2004 asserts that “a State enjoys immunity, in respect of itself and its property, from the jurisdiction of the courts of another State…”[9] Article 16 of this Convention further clarifies that this immunity applies to “warships, naval auxiliaries, and other vessels owned or operated by a State and used, for the time being, on government non-commercial service”.[10]

A detailed reading of Article 35 of the CCGR-3 — which allows the CCG to promulgate “temporary maritime security zones”, either for security or military related reasons — and then ensure denial of access to others therein — lends further arbitrariness to the area under consideration, in addition to the undefined “territorial waters”. Yet another provision, which makes a broad-based assertion of “surveying and mapping” in “waters under China’s jurisdiction” as “grave and serious”, is Article 263 of CCGR-3. In effect, this provision seeks to curb the freedom of other States with regard to the conduct of marine scientific research (MSR) in the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) of coastal States, and is hence in direct contravention of the stipulations laid down in Part XIII of the UNCLOS 1982.[11]

Consequently, even a prima-facie perusal of this provision is sufficient to draw alarm from a variety of stakeholders who value the ‘freedom, openness, and security’ of the Indo-Pacific as part of customary international law. For instance, the military survey activities, hitherto carried out by the US Navy’s auxiliary vessels such USNS Impeccable (ocean surveillance) ship or the USNS Bowditch (hydrographic ship) in the Chinese EEZ, could earlier pass off under the claim of MSR in accordance with UNCLOS 1982 — even though such missions were objected to by China and often physically obstructed. [12] However, such activities would henceforth, be considered as “grave and serious” as per the provisions laid down in CCGR-3, and thus be liable to appropriate penal/administrative action by the CCG and the Chinese legal system.

Impact on India’s Maritime Interests

Insofar as India is concerned, the promulgation and enforcement of CCGR-3 points to a number of ominous portents. About 55 per cent of India’s trade by volume transits the South China Sea and the interconnected sea lanes of the western Pacific. Indian Naval ships are present in the South China Sea and the adjoining maritime areas for at least two months in a year as part of their overseas operational deployment (OOD). In the current year (2024), three Indian Navy ships, viz., the guided-missile destroyer INS Delhi, the ASW Corvette INS Kiltan, and the underway replenishment ship, INS Shakti, were present in that region for two months (May and June), during which they called at the port of Singapore and various ports in Malaysia, Brunei, Vietnam, Cambodia and the Philippines.[13] These ships also carried out bilateral exercises with the navies of some of these countries. In addition, INS Shivalik, the indigenously built missile frigate, transited through the area on its way to Hawaii for the Rim of the Pacific Exercise (RIMPAC)-2024, and will probably return through the same area.

The fact that both, the CCG Law-2021 and the recently promulgated CCGR-3, are silent on the exclusion of warships and ‘ships on formal government employment’ — unlike UNCLOS 1982, which specifically makes this distinction, and stipulates separate rules for them — naturally raises uncomfortable questions as to their status under these Chinese domestic legal instruments. In this context, a “non-incident” [14] of 2011 certainly merits a mention. In July of 2011, the PLA Navy allegedly challenged an Indian amphibious landing ship, the Airavat, in the South China Sea, while the ship was undertaking a legitimate passage between Nha Trong and Hai Phong ports of Vietnam.[15] The challenge, heard over the ship’s radio to the effect that “you are entering Chinese waters”, even though the Indian warship was just about 45 NM from the Vietnamese coastline — and thus, well within the Vietnamese EEZ — was quite a surprising occurrence. The Indian Ministry of External Affairs (MEA), of course, called out this “non-incident” by stating:

“India supports freedom of navigation in international waters, including in the South China Sea, and the right of passage in accordance with accepted principles of international law. These principles should be respected by all.”[16]

However, the geopolitical situation in the South China Sea has taken a decisive downturn in the intervening period of more than a decade. With Beijing clearly displaying a far more aggressive stance in the area, — including in the adjacent waters around Taiwan and the East China Sea — the ambiguous and draconian provisions of the domestic CCG Law-2021 and the CCGR-3 afford undesirable discretion to the CCG to engage in some sort of misadventure against warships operating in the region.

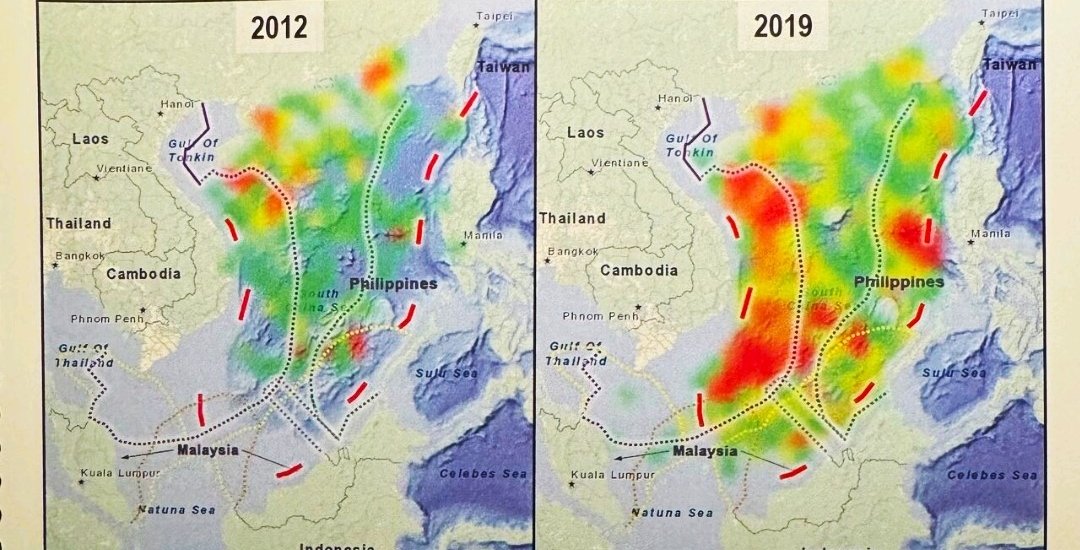

The Indian Naval ships’ deployments in the South China Sea and beyond — as part of India’s ‘Look East’ policy — have become more institutionalised over the last decade and half, with their activities, including port calls and exercises with the Southeast Asian countries, having increased in scale, scope and frequency. These interactive efforts require the Indian Naval ships to criss-cross the South China Sea across the so called ‘nine-dash line’ over which Beijing aims to exert greater control through the promulgation of domestic laws and regulations. It is, thus, entirely feasible that the CCG’s actions — duly empowered by statutes like the CCG Law-2021 and the CCGR-3 — will hereinafter be much more aggressive, if a situation similar to the one in 2011 (as described above) were to repeat itself.

Multilateral approach to check the Chinese Expansionist Agenda

It has been observed that long-drawn dialogue and discussions — particularly of the bilateral kind — with China rarely yield any results to the satisfaction of both the parties. India’s experience of the prolonged bilateral negotiations post-Galwan skirmish to convince China to revert to the status quo ante of April 2020 along the Line of Actual Control (LAC) in eastern Ladakh — with the 30th meeting on India-China border talks recently concluding with no tangible outcome[17] — bears testimony to this assertion. For the global community operating within the Indo-Pacific, the only course of action that has a reasonable chance of success against the ‘illegal and unlawful’ Chinese agenda of maritime expansionism through the empowerment of its maritime law and order agencies through overarching domestic regulations like the CCG Law-2021 and CCGR-3 region, is to vehemently oppose it in unison.

The US has certainly been challenging these excessive Chinese claims and assertions in the South China Sea and the Taiwan Strait, which tend to restrict the internationally recognised ‘freedom of the seas’ as afforded by UNCLOS 1982. It has, therefore, been mounting Freedom of Navigation operations (FONOP) to “uphold the rights, freedoms, and lawful uses of the sea recognized in international law” — the most recent one having been conducted by the guided-missile destroyer USS Halsey (DDG-97) on 10 May 2024.[18] Some European countries, as also Canada, too, have carried out joint transits through the Taiwan Strait. In fact, a Canadian frigate, HMCS Montreal (FFH-336) undertook a transit through the Taiwan Strait as recently as end-July 2024. While the Canadian Joint Operations Command termed the passage of its frigate “in accordance with international law”, China’s Eastern Theatre Command expressed its displeasure by stating that the event had created instability in the Taiwan Strait and had also undermined peace in the region.[19]

Over last couple of years, Philippines, for its part, has shown great courage and gumption in standing up to the blatantly offensive tactics of the CCG and the PAFMM vessels. Manila has brought Chinese efforts to capture various features in the Spratly chain of islands by use of strong-arm ‘grey zone’ tactics, to the notice of the world at large, through a sustained press and social media campaign. India, on its part, has also nuanced its position vis-à-vis the July 2016 ruling of the Permanent Court of Arbitration in favour of Philippines, by “underlining the need for peaceful settlement of disputes and for ‘adherence’ to international law, especially the UNCLOS and the 2016 Arbitral Award on the South China Sea.”[20]

Final Thoughts

The bottom line is that the Chinese hegemonic agenda of unilaterally changing the status quo in the South China Sea and its adjoining areas, as also by way of forcing stakeholders to accept the ‘new normal’ that it seeks to establish by overtly aggressive ‘grey zone’ warfare, implied muscle flexing through the PLA Navy and enacting wholly unacceptable domestic laws which are in contravention to the established global conventions, must not be allowed to gain traction.

Towards that objective, the adoption of a multilateral approach and presentation of a unified front to oppose the Chinese expansionist mindset by calling out the restrictive provisions of each and every domestic Chinese Law and regulation that seeks to challenge the extant rules-based order, and threatens the freedom of navigation and overflight, merits serious consideration. A fleeting glimpse of this front taking shape was somewhat apparent when eight countries — including India, Malaysia, Vietnam, the Philippines, Russia and Taiwan — officially called out the Beijing’s endeavour to reappropriate greater areas under its control through unilateral cartographic overreach of promulgating a ‘ten-dash line’ in August 2023.[21]

It is, therefore, in the interest of all States that have a stake in upholding a “free, open, secure, and inclusive” Indo-Pacific and other parties across the globe, and who would be adversely impacted by such Chinese revisionist propensities, to come together and act in unison with greater intensity and visibility. The promulgation of CCGR-3 presents just the right opportunity for the global strategic, legal and maritime community to do just this — as an immediate measure.

******

About the Author:

Captain Kamlesh K Agnihotri, IN (Retd) is a Senior Fellow at the National Maritime Foundation (NMF), New Delhi. His research concentrates on the manner in which the maritime ‘hard security’ geostrategies of India are impacted by those of China, Pakistan, Russia, and Turkey. He also delves into holistic maritime security challenges in the Indo-Pacific and their associated geopolitical dynamics. Views expressed in this article are personal. He can be reached at kkumaragni@gmail.com

Endnotes:

[1] National Institute of Defense Studies, Japan, “East Asian Strategic Review 2011”, 111-112, https://www.nids.mod.go.jp/english/publication/east-asian/pdf/2011/east-asian_e2011_04.pdf

[2] The Chinese Letter CML/18/2009 of 07 May 2009 in response to Vietnam’s submission dated 07 May 2009, to the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf. https://www.un.org/depts/los/clcs_new/submissions_files/vnm37_09/chn_2009re_vnm.pdf

[3] The Global Times, “Sansha new step in managing S. China Sea”, July 18, 2012, https://www.globaltimes.cn/content/717193.shtml

[4] Reuters, “China says “board and search” sea rules limited to Hainan coast”, December 31, 2012, https://www.reuters.com/article/world/china-says-board-and-search-sea-rules-limited-to-hainan-coast-idUSDEE8BU04I/

[5] Xinhua, “Coast Guard Law of the People’s Republic of China”, January 22, 2021”, http://www.xinhuanet.com/2021-01/23/c_1127015293.htm. English translation of this Law is available at https://demaribus.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/2021-02_11_china_coast_guard_law_final_english_changes-from-draft.pdf

[6] Gateway House, “China’s worrisome Coast Guard laws”, Feb 11, 2021, https://www.gatewayhouse.in/china-coast-guard-laws/. Also see Raul (Pete) Pedrozo, “Maritime Police Law of the People’s Republic of China”, U.S. Naval War College, https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/ils/vol97/iss1/24/

[7] Lawyers’ Web portal m.055110.com, “(2024) Provisions on Administrative Law Enforcement Procedures for Coast Guard Agencies”, May 16, 2024, https://m.055110.com/law/1/31824.html. English translation by Google. Henceforth be referred to as ‘CCGR-3’.

[8] Article 25 of Coast Guard Law 2021 uses the phrase “…waters under my country’s jurisdiction…” while explaining the authorization provided to the provincial Coast Guard Bureau to delimit temporary maritime security zones. Supra note 5.

[9] United Nations Treaty Collections, “United Nations Convention on Jurisdictional Immunities of States and Their Property”, December 2004, https://treaties.un.org/doc/source/recenttexts/english_3_13.pdf, Article 5.

[10] Ibid, Article 16. Para 2 has been paraphrased by the Author to impart better clarity.

[11] UNCLOS 1982 provides the legal umbrella for MSR, wherein Part XIII, comprising articles 238 to 265, lays down the rights of other states to conduct MSR for peaceful purposes in the EEZ of coastal states, as also the rights of coastal states to regulate MSR in their EEZ.

[12] For an overview of incidents involving the UN Navy Auxiliary ships, the Impeccable and the Bowditch, see Pedrozo Raul, “Close Encounters at Sea: The USNS Impeccable Incident”, Naval War College Review, Summer 2009, Vol. 62, No. 3, 101, https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/ADA519335

[13] Press Information Bureau, “Indian Naval Ships Delhi, Shakti, and Kiltan Arrived at Singapore, as a part of Eastern Fleet Deployment to South China Sea”, 07 May 2024, https://pib.gov.in/ PressReleseDetail.aspx?PRID=2019815.

Also see: “Visit to Cam Ranh Bay, Vietnam by Indian Naval Ship Kiltan”, https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=2020379; “Indian Naval Ships Delhi, Shakti, and Kiltan Complete their Visit to Manila, Philippines as part of the Operational Deployment of the Eastern Fleet to the South China Sea”, https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=2021395

[14] The phrase, “non-incident” is the author’s own creation to refer an event, a serious doubt about the occurrence of which continues to persist, but it nevertheless, still managed to draw significant publicity.

[15]Indian Ministry of External Affairs, “Incident involving INS Airavat in South China Sea”, 01 September 2011, https://www.mea.gov.in/media-briefings.htm?dtl/3040/Incident+involving+INS+Airavat+in+South+China+Sea

[16] Ibid.

[17] Indian Ministry of External Affairs, “30th Meeting of the Working Mechanism for Consultation & Coordination on India-China Border Affairs”, 31 July 2024, https://www.mea.gov.in/press-releases.htm?dtl/38052/30th+ Meeting+of+the+Working+Mechanism+for+Consultation++Coordination+on+IndiaChina+Border+Affairs

[18] The US Navy, “U.S. Navy Destroyer Conducts Freedom of Navigation Operation in the South China Sea”, 10 May 2024. https://www.navy.mil/Press-Office/News-Stories/Article/3771407/us-navy-destroyer-conducts-freedom-of-navigation-operation-in-the-south-china-s/

[19] Heather Mongilio, “Canadian Frigate Transits Taiwan Strait, Chinese Forces Monitor Operation”, USNI News, 01 August 2024. https://news.usni.org/2024/08/01/canadian-frigate-makes-taiwan-strait-transit-as-china-forces-monitor#:~:text=Canadian%20frigate%20HMCS%20Montreal%20(FFH,in%20accordance%20with%20international%20law.

[20] Government of India, Ministry of External Affairs, “Joint Statement on the 5th India-Philippines Joint Commission on Bilateral Cooperation.” 29 June 2023. https://mea.gov.in/bilateral-documents.htm?dtl/36743/ Joint_Statement_on_the_5th_IndiaPhilippines_Joint_Commission_on_Bilateral_Cooperation.

[21] Ma Zhenhuan, “2023 edition of national map released”, China Daily, 28 August 2023. https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202308/28/WS64ec91c2a31035260b81ea5b.html

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!