Introduction

Seeking to achieve initial operational capacity for seabed warfare by 2026, France is a nation putting in concerted effort to achieving competence in this domain. Beginning with a formalised public strategy, which lays out the ability that the French seek to achieve and the manner in which they seek to achieve it, to conducting seabed warfare deployments (Operation CALLIOPE),[1] the French seem to be leading the way in acquiring advanced seabed warfare capacities and capabilities. In fact, the French Navy has recently included a “seabed control serial” in their bilateral exercise with the Italian Navy where they utilised an Autonomous Underwater Vehicle and a Remotely Operated Vehicle to “counter malicious action on underwater infrastructure”.[2] Therefore, the French strategy offers a useful blueprint for India to formulate its own seabed warfare strategy or refine it if one already exists in the classified domain. It analyses the French seabed warfare strategy and extracts from it aspects that may inform India’s own strategy for the seabed.

France and Seabed Warfare

The Ministère des Armées (French Ministry of Armed Forces) in February 2022, released a Working Group Report entitled “Seabed Warfare Strategy” (hereinafter referred-to as the “Strategy”) to offer an ambition and a roadmap to meet the challenges in this “increasingly disputed area” as conflicts have “now effectively extended to the seabed”.[3] During a press conference, the ex-French Minister of Defence put the end-state of the new strategy as being to “equip the French military with the ability to reach depths of 6,000 meters, or nearly 20,000 feet…as this makes it possible to cover 97 per cent of the seabed and effectively protect our interests, including submarine cables.”[4]

Seabed Warfare Operations, according to the “Strategy”, include “implementing, deploying and utilising fixed, semi-fixed or mobile underwater capabilities able to operate towards, from, and on the seabed, either independently or in a network”.[5]

The geographical area on which the “Strategy” is primarily focused is divided into two subpoints: (i) the territorial sea and French EEZ, and (ii) any area of operational interest for the freedom of action of French armed forces and the protection of the country’s national interests.[6] Therefore, it is evident that the scope of the “Strategy” is not limited to areas within French jurisdiction and encompasses even those areas which lie beyond national jurisdiction as long as they are of operational and national interest. This is of significance as the total area of the French maritime zones, with the continental shelf extensions in force, is 10,911,921 sq km[7] Of this, the French EEZ in the Indian Ocean — which is 20% of its total EEZ (roughly 2,182,384 sq km) — is 10% of the total surface of the Indian Ocean.[8] Since the Indian Ocean is of particular interest to India, a strategy that aims to “control” 10% of it certainly needs careful study. Moreover, the inclusion of a catch-all geographic area with reference to “operational and national interests” makes the scope of the “Strategy” extraordinarily wide.

|

Source: https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2016/01/13/drops-in-the-ocean-frances-marine-territories |

A Coordinated Effort

The “Strategy” follows the “France 2030 Investment Plan” (unveiled by then-President Macron in 2021), which includes “explore the seabed” as an express objective of the plan. [9] In fact, the “Strategy” explicitly identifies itself to be “fully integrated” into an interagency dynamic, focusing upon the seabed, and leading from the “2015 National Strategy for The Security of Maritime Areas”, the “National Strategy on the Exploration and Exploitation of Deep Seabed Mineral Resources”, and the “France 2030 Investment Plan”.[10] Therefore, it is evident that there is significant attention being paid by France towards the seabed as a strategic domain. The “Strategy”, in fact, specifies that the “seabed is not a compartment or a field in its own right”[11] but is, nonetheless, a “new area of conflict”. Therefore, it needs to be read within the broader themes of ‘undersea warfare’ and ‘maritime security’. In fact, Rear Admiral Cédric Chetaille — the French Navy’s deputy chief for operations, and director of seabed capability development — has stated that such capability is to “multiply effects in naval warfare, better co-ordinate with anti-submarine warfare to ensure success in multi-domain and joint operations, recognising the specific nature of seabed warfare domain assets and command and control”.[12]

It is also pertinent to note the while an inter-agency dynamic certainly exists, given the vastly varying nature of activities related to the seabed, there is a difference in approach that the strategies of individual agencies have to the same domain. There may be complementarities as well as conflicts in these approaches, which may affect the implementation of these strategies. A key example is the “lead agency in-charge” of achieving these objectives. The “Strategy” which is one that has been promulgated and led by the Ministry of the Armed Forces, contextualises the seabed in terms of conflict and defence, while the “France 2030…” — which is a whole-of-government policy focused upon investment facilitation — entrusts the lead for the seabed objective to the Ministry for Marine Affairs, the Ministry of Higher Education and Research, and the Ministry for Industry.[13] 350 million euros have been allocated to develop scientific research programs to explore the deep sea and promote French manufacturers to provide the equipment required for such research. This, as will be dilated upon subsequently, overlaps with the stipulated aim of the “Strategy”, namely, to develop a ‘Defence Technological and Industrial Base’ for equipment necessary for seabed warfare. Therefore, coordination between these ministries to ensure directed, focussed, and consolidated effort acquires importance.

The “Strategy”

The “Strategy” represents an ambition. France has identified the ever-increasing strategic and economic importance of the seabed and seeks to prepare itself to capitalise upon the opportunities that arise once technological advances make the seabed more accessible. The “Strategic Update” of 2021 had stated that the seabed is increasingly becoming the setting for power struggles.[14] Therefore, while protection of submarine installations, such as communication cables and pipelines, is an important aspect of the seabed effort, the broader ambition of the Strategy is to “control” the seabed.[15] This comes from a reading of the seabed as an “Undersea Far West” subject to “strategic piracy” due to the increasing competition for resources, heightened military activity, the territorialisation of the seabed, increasing sensitive seabed installations, and the adoption of aggressive fait accompli policies by States.[16] The disputed international status of the seabed, weak international institutions (which the “Strategy” calls the “lost gamble of global governance”), the hybrid nature of submarine activity, and the use of the law as a tool to secure claims, all taken in aggregate, have prompted France to assert “strong national policies” vis-à-vis the seabed.[17]

The key end-objectives of the Strategy have been outlined as:

- Guarantee freedom of action for our armed forces in the air-maritime environment

- Contribute to the protection of our underwater installations (including submarine communication cables)

- Guarantee French interests in the exploration and exploitation of mineral and energy resources, in particular in areas under national jurisdiction

- While being capable of posing a credible threat to the interests or forces of a potential enemy tempted to attack the interests of France or its strategic partners[18]

Interestingly, the “Strategy” does not focus on protecting the seabed but rather on controlling it. The control of the seabed is to ensure both offensive and defensive action not only on the seabed but also in the broader “air-maritime environment”. This includes protecting underwater infrastructure and the economic interests of France underwater.

The strategic lines of effort to achieve the end objectives are two-fold: (1) “extend control of maritime areas to the seabed to guarantee our freedom of action” and (2) “strengthening our strategic autonomy”. [19] The “Strategy” seeks to preserve and bolster capacity for anticipation and freedom of action in underwater areas to contribute to national resilience.[20]

Each strategic line of effort is, in turn, supported by one or more operational lines of effort. The first strategic line of effort, i.e., the extension of control is sought in four ways:[21]

- Develop knowledge of the seabed. This step acquires significance due to the current lack of knowledge of the undersea environment. Such knowledge not only supports France’s nuclear posture of deterrence at sea (conducted by the ballistic missile submarines of the French Strategic Ocean Forces) but also assists in assessing threats, establishing modes of action, and optimising the performance of sensors.[22] This involves a deep understanding of bathymetry and gravimetry to allow for the use of inertial navigation systems to ensure safer and more precise navigation. Additionally, it provides for greater autonomy as it reduces reliance on external positioning systems such as GPS, Galileo, etc.[23] Further, understanding sediment properties is important for underwater detection using ultra-low frequencies as they affect acoustic propagation. This requires innovation in acoustic, optical, and magnetic or electromagnetic technologies. The focus is on innovation and the development of mobile underwater systems equipped with onboard sensors with operating capacity at a depth of 6,000 metres in synergy with the current “Hydrographic and Oceanographic Capacity of the Future Program” (CHOF) of the French Hydrographic and Oceanographic Office (SHOM).[24]

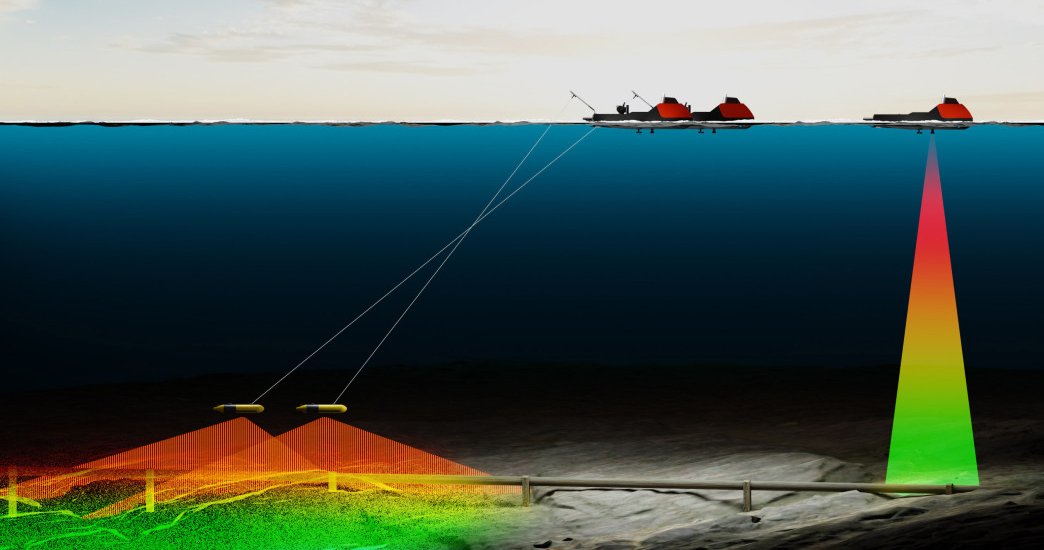

- Monitor the seabed and submarine area. This objective is to be achieved by monitoring the seabed, as also monitoring ‘from’ the seabed. Described as an activity to be undertaken during peacetime, it seeks to ensure the ability to autonomously monitor, detect, classify, and even search for objects or any potential threats that could impede freedom of action for the French armed forces and the integrity of French submarine installations. It is recognised that such threats could exist both on the seabed and the water column above it.

With regard to monitoring the water column ‘from’ the seabed, the objective is the protection of approaches, supporting a force projection operation, or discouraging a potential enemy.[25] Ensuring the security of approaches is essential to “deploy air-maritime forces far from their bases” and has been explicitly linked to nuclear deterrence operations at sea, and ballistic missile submarines operating from the Ile Longue base and the French aircraft carrier, the Charles de Gaulle, from Toulon.[26] While both these bases are in ‘Metropolitan France’, it is foreseeable that surveillance systems may be placed in the Indian Ocean to ensure safe passage of these French assets, and eventually, such vessels may well be bases in French Overseas Territories within the Indian Ocean.

The “Strategy” stresses the role of underwater vehicles (AUVs, ROVs) equipped with complementary sensors that are compatible with naval or possibly even civilian platforms to carry out search missions discreetly and in semi-permissive or non-permissive environments.[27] Underwater vehicles, in combination with other fixed, semi-fixed or mobile platforms, are envisaged to be networked with one another so as to allow for sensor-complementarity, rationalisation, and comprehensive coverage ‘of’ and ‘from’ the seabed.[28]

- Take action ‘on’, ‘from’ and ‘towards’ the seabed. Characterising the seabed as “an extended field of action”, the ambition relates to being able to conduct operations such as targeted investigations, neutralisation, destruction, and recovery of sensitive objects, and the restoration of an underwater asset in deep waters.[29] Towards these ends, France seeks to acquire the capability to operate in deep water conditions of depths up to 6000 m which makes 97% of the seabed accessible. It is felt that French undersea warfare actions and capabilities need to extend deeper as there is going to be greater recourse to subaquatic courses of action. As such, they aspire to acquire the ability to “horizontally” enter complex and disputed areas where the operation can be launched and executed in the deep sea/seabed domain. Here, the French seek to develop a tactical advantage in depth through which they could access environments which otherwise may be difficult to access. French assets could go deeper to avoid any obstacles and more effectively either attack or defend infrastructure at depths.

The “Strategy” identifies that current French ability is limited to 2000 m by the ‘Human Diving and Underwater Intervention Unit’ (CEPHISMER).[30] Deeper access up to 6000 m can be achieved in very limited numbers by IFREMER which is the French National Institute for Ocean Science, i.e., in a civilian capacity for deep-sea resource exploration. Therefore, the ambition to move from 2000 m to 6000 m is steep or requires a repurposing of IFREMER assets for military purposes.

- Make further use of opportunities arising in the current legal framework. The French seek to use the law – both national and international – to consolidate their “Strategy”. Interestingly, the “Strategy” seeks to adopt a legal posture that “integrate[s] compliance with international law by maritime powers” (emphasis added).[31] On the international law front, the French position UNCLOS as the “relevant and coherent framework” for meeting the challenges inherent in seabed warfare.[32] By way of corollary, they seek to prevent the use of UNCLOS by States to control maritime areas of French interest and have expressly indicated their intention to continue their activities in disputed areas such as South China Sea to maintain “freedom of navigation”.[33] “Freedom of navigation” is held to be integral to “freedom of manoeuvre” and “free access to resources”. Activities highlighted include strategic guidance and sharing positions at forums such as UN-DOALOS.

On the national front, the French seek to develop less permissive regulations, improve knowledge of maritime activities, and ensure that the law keeps pace with the technology. These laws seek to address the laying and protection of submarine cables (Decree 2013-611), AUV navigation and maritime drones (Ordinance No. 2021-1330), and marine scientific research in areas of French maritime jurisdiction, including creating “areas within the protection of national defence interests” requiring authorisation and rules relating to publication of data.[34]

With respect to the second strategic objective, viz., strengthening strategic autonomy, emphasis has been placed on capitalising technological advancements, developing a ‘Defence Technological and Industrial Base’ (DTIB), and partnerships.[35]

The advancements currently in focus relate to vehicle endurance, autonomous decision-making, sensor miniaturisation, data processing, submarine communications, and robotics.[36] Further, since autonomous underwater vehicles and remotely operated vehicles form the crux of the French endeavour to achieve their strategic ambition, specific lines of effort have been identified with respect to each vehicle:

AUVs: Advancements need to be achieved in:[37]

- Energy, including battery technology, and induction charging for seabed charging stations (power storage and distribution).

- Navigation, including component miniaturisation, and improved gravimetry and processing capability.

- Detection, including AI-enabled detection systems for search, classification, and monitoring of objects on the seabed including submarine cables.

- Communications, including improvement of data rate, range, and security for underwater communications.

ROVs: Advancements primarily relate to the field of robotics to enhance precision, endurance, and mission diversity. These include joystick control, diversity of information collection, battery storage, and better effector manoeuvrability.[38]

As may be seen, the ability that the French seek to acquire for seabed warfare is reflected in the capacities that they seek to develop in the AUVs/ROVs. It is pertinent to highlight that the emphasis is not only on AUVs/ROVs but also upon those which can operate at depth. Hence, the endeavour is technology driven. This as per the “Strategy” needs to be given effect through the DTIB, i.e., the defence manufacturing-industry within France. Since expertise beyond 3000 m is limited to civilian operators engaged in scientific and oceanographic research, the “Strategy” envisages partnerships with civilian operators for development for technologies that are inherently dual use in nature.[39] It has been identified that as per current capacities off-the-shelf vehicles cannot be produced and, of the range of technical capacities required — lighting, electro-optical imaging in high pressure environments, positioning, propulsion, robotics, and electric optic carrier cables — the French industry can address only a limited number of areas for ROV production (which those are that has not been developed by the “Strategy”).[40] Current capacities and capabilities with reference to AUV production have not been identified. Hence, keeping in mind the sensitivities of sovereign capabilities, strategic, and economic interests of France, synergy is sought between the “France 2030 Investment Plan”, civil operators, and international partners.[41]

In fact, the French Navy is leasing deep-sea assets from the private sector and testing them in their first seabed warfare operation, Op CALLIOPE, to evaluate their capabilities, and how and where they can be utilised.[42] Therefore, there is integration between not only the civil branches of government but also the private sector to accelerate the acquisition of capacities and capabilities to engage in seabed warfare operations.

Potential international collaborations are sought in areas that France “will not be able to cover entirely”.[43] The “Strategy” highlights protection of submarine installations and resources including through intelligence sharing on submarine activity.[44] Every such partnership needs to be balanced against the strategic and economic advantages that France has, especially in defence manufacturing.[45] India has been identified as a “competitor” in the domain of seabed warfare and is acknowledged as a major hub of submarine cable routes in the Indian Ocean. The “Strategy” notes that India is developing unmanned high-endurance platforms designed for mine warfare and undersea operations or seabed mapping.[46] India has also been identified as an existing “partner” in both mine warfare and in hydrography, oceanography, and meteorology.[47] Therefore, the broad nature of seabed warfare and the convergences in interests between India and France in developing seabed capabilities presents an opportunity for enhanced collaboration.

As outlined in the “Strategy”, the capability-building process has an accelerated, short-term phase, seeking to access seabed surveillance and intervention capabilities up to 6,000 m, using AUVs and ROCs already tested by the oil and gas, and/or the scientific research industry. It then seeks to build long-term capabilities through further “deep sea” AUV/ROV production, DTIB maturity, and generating research and skilled personnel for seabed warfare.[48] All three strands could potentially offer scope for collaboration between India and France.

India and the Deep Sea: Recommendations

India, too, has identified the importance of possessing the capacity and capability to harness the potential of the deep sea in making India’s economy “bluer”. The “Deep Ocean Mission” launched in 2021 seeks to develop technologies for deep sea mining, particularly a manned submersible capable of reaching depths of 6,000 m.[49] While the focus of this initiative is to support the growth of India’s blue economy, a critical component is the attempt to indigenise technology by collaborating with academia and private industry.[50] Attempts are on to bolster Indian industry to cater to the technological needs of this initiative. On the defence front, the Indian Navy has a roadmap to enhance R&D in military technology, called “Swavalamban 2.0”, which formulates requirements that may be taken-up for indigenisation by Public Sector Undertakings (PSUs), the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO), and the private industry.[51] Uncrewed underwater vehicles (UUVs) form a part of this indigenisation plan with a need being highlighted to pursue these capacities “with vigour” especially for underwater weapons and sensors.[52] This is clearly an area that is gaining policy attention in India. It must be noted that this represents the information and policy formulations that are available in the open domain. A further and deeper analysis on Indian developments will, indeed, be conducted later in this ongoing series of research articles. It is possible that India has or is developing a strategy or concept of operations for seabed warfare that has not been made public. This notwithstanding, quite a few aspects can be incorporated from the French approach to seabed warfare:

- Whole-of-Government Approach. It is important that the seabed as a domain receives holistic policy engagement. For the French, their policy on the seabed has progressed on three prongs, i.e., resources, investment, and defence. The “Strategy” explicitly identifies synergy between these three prongs (which represent independent policies) for effectiveness and efficiency. Even though synergy is sought between the three, the lack of an identified inter-agency coordination mechanism is likely to impede effective collaboration and coordination. Therefore, India must, in its own seabed strategy identify an inter-agency coordination mechanism, a role which the National Security Council Secretariat would be well-placed to perform. Given that the “Deep Ocean Mission” and the Swavalamban initiative are led by different government agencies, with the seabed being only one of their several objectives, a coordination mechanism for the seabed is important. This will also lead to better civil-military collaboration to acquire capacities more efficiently. Deep sea technologies that are used for scientific or commercial purposes can certainly be adapted for military use, making such technologies inherently dual use in nature. Therefore, it is important that there is better coordination between the civil, private, and military actors to focus efforts towards a common goal.

- Focus on Innovation in Deep-sea Technologies. A crucial and central feature of the French seabed warfare strategy and that country’s general policy focus on the seabed is the emphasis laid on investing and innovating in deep-sea technologies. The environmental conditions of the deep sea render the entire endeavour technologically intensive. Further, much of this technology is still developing and is quite sensitive due to its potential strategic and dual-use nature. It is precisely because of this that India’s “Deep Ocean Mission” emphasises indigenous development. Such development should progress on the defence front as well. The “Naval Innovation and Indigenisation Organisation” (NIIO) and the “Technology Development Acceleration Cell” (TDAC) operating under it should actively seek out and promote deep sea technologies.[53] Similarly, deep-sea technologies must form part of the problem-statements under the “Innovations for Defence Excellence” (iDEX) initiative, which partners with academia for defence innovation.[54]

- Development of a Domestic Industrial Base. This forms the next step after innovation and design. France has placed significant emphasis upon developing a domestic defence technological and industrial base in order to achieve strategic autonomy in this space. This has, indeed, also been a critical component of the Indian Navy’s “Swavalamban 2.0” Hardware for deep sea technologies need to receive requisite attention under this programme, too.

- Identification of Comparative Advantages and Partnerships. Given the urgency of the issue, the nascency of the technology, and considerations of cost and scale, developing strategic partnerships with friendly countries is important to provide a boost to India’s efforts to prepare for seabed warfare. This was echoed by Hon’ble Defence Minister, Shri Rajnath Singh when he stated that it was important to ensure that we are not “re-inventing the wheel”.[55] While these remarks were made in the context of ensuring that the technology being developed is not already available in the market, it could well be applied in the context of availability with partner countries with whom India has strategic partnerships and who may be willing to collaborate with India in this space. For this purpose, it is important to identify the areas in which India possesses comparative advantages vis-à-vis other nations and can hence enter into mutually beneficial partnerships. The French Navy for instance is focussing on a) “building its overall capacity for operating maritime uncrewed systems; improving capability to use complex underwater acoustics; and improving capability to process underwater data”.[56] These areas have potential for collaboration between the two navies.

- Personnel Training Programmes. It is important, within this domain, to focus not only upon ‘capacity building’ but also upon ‘capability enhancement’. As highlighted above, the focus area of the French Navy is not just in acquiring new technology but also acquiring the capability to use and operate them effectively. The need for research and establishing programs for skilling personnel also forms part of the formal strategy. Since investments in personnel have long gestation periods, it is important to start creating the structures and making such investments as soon as feasible.

Conclusion

The French Seabed Warfare Strategy offers a useful blueprint to inform India’s own approach to the seabed as a domain of warfare or conflict. It also offers potential areas in which the France and India may collaborate to include the seabed as part of their strategic relationship.

******

About the Author:

Soham Agarwal, a Delhi-based lawyer holds a Bachelor of Law (Honours) degree from the University of Nottingham, UK. He is currently an Associate Fellow with the Public International Maritime Law Cluster of the National Maritime Foundation, New Delhi. His research is focused upon issues relevant to the seabed, maritime infrastructure, and seabed warfare. He may be contacted at law10.nmf@gmail.com

Endnotes:

[1] Dr Lee Willett, “French Navy Seeks 2026 IOC for Seabed Warfare Capability”, Naval News, 29 May 2024 https://www.navalnews.com/event-news/cne-2024/2024/05/french-navy-seeks-2026-ioc-for-seabed-warfare-capability/

[2] Ibid

[3] Seabed Warfare Strategy, (French Ministry of Armed Forces, 2022), 8 https://www.archives.defense.gouv.fr/content/download/636001/10511909/file/20220214_FRENCH%20SEABED%20STRATEGY.pdf

[4] Njall Trausti Fridbertsson, “Protecting Critical Maritime Infrastructure – The Role Of Technology”, NATO Parliamentary Assembly, 06 April 2023 https://www.nato-pa.int/download-file?filename=/sites/default/files/2023-04/032%20STC%2023%20E%20-%20CRITICAL%20MARITIME%20INFRASTRUCTURE%20-%20FRIDBERTSSON%20REPORT.pdf

[5] Seabed Warfare Strategy, (French Ministry of Armed Forces, 2022) p38

[6] Ibid p28

[7] “Superficies des espaces maritimes de souveraineté et de juridiction de la France”, French Naval Hydrographic and Oceanographic Service, 26 January 2023 https://limitesmaritimes.gouv.fr/sites/default/files/2023-03/Superficies_espaces_maritimes_Fr_230126.pdf

[8] “France in the south-west Indian Ocean”, France Diplomacy, Ministry of Europe and Foreign Affairs, last updated July 2024 https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/en/country-files/regional-strategies/indo-pacific/the-indo-pacific-a-priority-for-france/france-in-the-south-west-indian-ocean/

[9] “France 2030 : One Year Of Action To Live Better, Produce Better And Understand Better”, Press Kit, 18 November 2022 https://investinfrance.fr/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/FR-2030_Dossier_Presse_A4-v07-BAT-EN.pdf

[10] Seabed Warfare Strategy, (French Ministry of Armed Forces, 2022), 27

[11] Seabed Warfare Strategy, (French Ministry of Armed Forces, 2022), 40

[12] Dr Lee Willett, “French Navy Seeks 2026 IOC for Seabed Warfare Capability”

[13] Seabed Warfare Strategy, (French Ministry of Armed Forces, 2022), 29

[14] “Strategic Update 2021”, (French Ministry of Armed Forces, 2021)

[15] Seabed Warfare Strategy, (French Ministry of Armed Forces, 2022), 8

[16] Seabed Warfare Strategy, (French Ministry of Armed Forces, 2022), 24-26

[17] Seabed Warfare Strategy, (French Ministry of Armed Forces, 2022), 25

[18] Seabed Warfare Strategy, (French Ministry of Armed Forces, 2022), 27

[19] Ibid

[20] Ibid

[21] Ibid, 27-33

[22] Ibid, 28

[23] Ibid, 28

[24] Ibid, 42

[25] Ibid, 30

[26] Ibid

[27] Ibid, 30

[28] Ibid

[29] Ibid, 32

[30] Ibid

[31] Ibid

[32] Ibid, 33

[33] Ibid

[34] Ibid, 34

[35] Ibid, 37

[36] Ibid, 34

[37] Ibid, 35

[38] Ibid, 35

[39] Ibid, 37

[40] Ibid, 36

[41] Ibid, 37

[42] Dr Lee Willett, “French Navy Seeks 2026 IOC for Seabed Warfare Capability”

[43] Ibid, 37

[44] Ibid

[45] Ibid

[46] Ibid, 20

[47] Ibid

[48] Ibid, 43-44

[49] “Deep Ocean Mission”, Ministry of Earth Sciences, last accessed 06 August 2024 https://moes.gov.in/schemes/dom?language_content_entity=en

[50] Ibid

[51] Swavlamban 2.0 Indigenisation Plan, (New Delhi: Directorate of Indigenisation, Integrated Headquarters, Ministry of Defence (Navy), 2023) https://www.ddpmod.gov.in/sites/default/files/SWAVLAMBAN%202.0.pdf

[52] Ibid, 1

[53] “Naval Technology Acceleration Council Meeting”, Press Information Bureau, 23 March 2022 https://pib.gov.in/Pressreleaseshare.aspx?PRID=1808821

[54] “Major announcements by Raksha Mantri during the plenary session of ‘Swavlamban 2.0”, Press Information Bureau, 04 October 2023 https://mod.gov.in/sites/default/files/PR041023.pdf

[55] Ibid

[56] Dr Lee Willett, “French Navy Seeks 2026 IOC for Seabed Warfare Capability”

Fig 1: France’s Exclusive Economic Zones

Fig 1: France’s Exclusive Economic Zones

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!