Introduction

The international shipping lanes that crisscross the vast expanse of the world’s oceans serve as the great highways of India’s trade endeavours, carrying nearly 95 per cent of her trade by volume and 68 per cent by value. However, beneath this impressive statistic lies a concerning reality: KPMG [[1]] reports that merely 8 per cent of this trade is carried on Indian-flagged or owned vessels, leaving the majority to be transported by foreign-flagged ships. An analysis of the prevalence of Chinese-built or controlled vessels in Indian shipping becomes imperative, given the increasingly influential role that China holds in the shipbuilding market. As of 2022, China commanded an imposing 47 per cent of the global shipbuilding industry, which surged by 15.5 per cent within that year alone, as reported by Clarkson[[2]].

Reports also throw light on an emerging trend wherein Indian entrepreneurs find an advantage in Chinese funding, utilising debt or leasing arrangements to shift assets beyond the jurisdiction of Indian shipping regulations. [[3]] The allure of lower interest rates and a well-developed lease financing ecosystem has made Chinese financiers a preferred choice for shipping capital. The practice of utilising foreign-built vessels may not in itself be a cause for concern. However, as the ship-finance landscape becomes increasingly dominated by leasing models, the situation takes on a more intricate hue. The ownership of vessels being vested in entities from adversarial nations, while chartering is managed by others, has direct and cascading repercussions on India’s trade dynamics and subsequently, its economic security. With growing seaborne trade, India has a significant exposure to marine freight rates. As per reports, every year an estimated USD 75 Billion [[4]] is paid to foreign shipping companies, impacting India’s foreign exchange reserves. This translates to approximately 93 per cent of Indian-origin or international destination cargo shipments and 39 per cent of Indian cargo is shipped on foreign vessels[[5]].

It is therefore imperative to strengthen India’s shipbuilding industry, as it extends beyond the realm of business and economic interests, into matters of security and strategy. Yet, the path towards enhancing shipbuilding is rife with complexities, interwoven with the broader shipping sector and the global economy. Shipowners and shipping enterprises will only order new vessels if it is profitable, which is in turn subject to the dynamics of the global economy, chartering contracts, and geopolitical events. This article embarks on an exploration of Indian shipbuilding within the expansive framework of its economy. By examining the intricate challenges and impediments that surround this domain, including problems associated with ship financing, the aim is not to offer tailor-made solutions but rather to spark deliberation and discourse. The labyrinthine nature of this issue underscores the importance of a nuanced perspective, necessitating collaborative engagement to chart a path ahead.

State of the Indian Economy and Shipbuilding

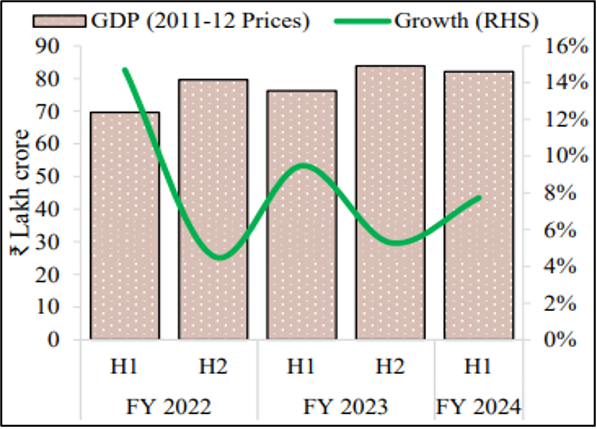

As per the Half-yearly Economic Review [[6]], of November 2023, India’s GDP grew by 7.7 per cent in H1 of FY 24 (Apr-Sep 23). Supply chains eased, global inflation declined, and Advanced Economies (AEs) showed resilience. The government of India’s measures have moderated due to stable and declining core inflation. The Government’s capital expenditure has accelerated the investment rate. Prudent fiscal policies amidst the fiscal risks prevailing globally are supporting the country’s economic growth prospects. As a result of this macroeconomic stability, India is expected to grow at 7.3 per cent [[7]] during the current fiscal year.

Figure 1: India’s GDP in FY 24

(Source: MER- November 2023)

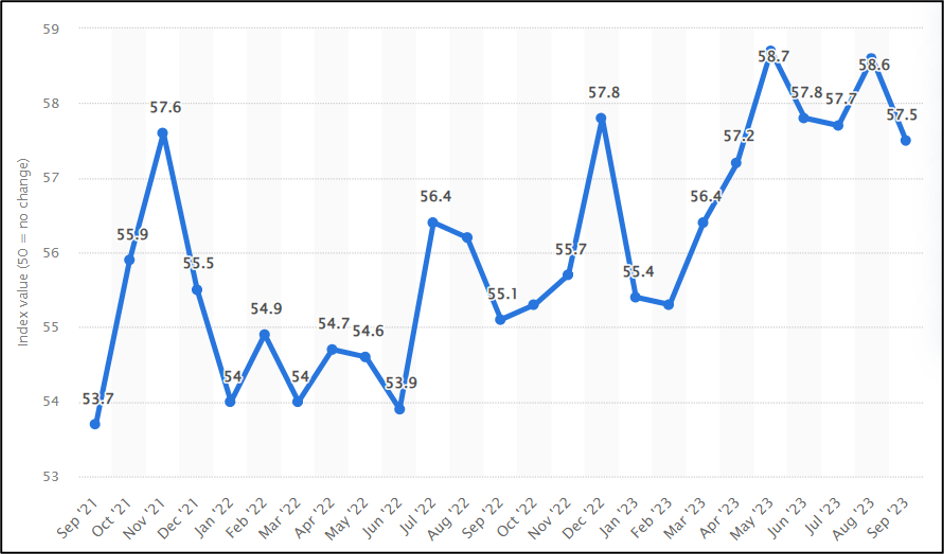

The impact of India’s Macroeconomic Stability is also evident in India’s manufacturing sector which showcased an impressive performance. The seasonally adjusted Purchasing Managers’ Index® (PMI®)[[8]] rose to 57.5 in September 2023 from 55.4 in January 2023, indicating the strongest improvement in the health of the manufacturing sector since September 2021.

Figure 2: India’s Manufacturing PMI

(Photo Courtesy: Statista [[9]])

This growth was driven by robust demand conditions, with factory orders rising at the fastest pace since September 2021, and a surge in sales that paved the way for stronger increases in production, employment, and quantities of purchases. Additionally, the manufacturing sector witnessed record accumulation in input inventories, showcasing better preparedness in managing supply chains. Despite generally subdued global demand for inputs, the manufacturing sector managed to control input price inflation, leading to a solid and quicker increase in output charges. Furthermore, exports played a vital role in boosting total new orders, with companies registering the quickest expansion in international sales in six months. Despite a robust economy and manufacturing sector, the landscape in the shipbuilding industry presents a more sobering picture. The Annual Report (2022-23) [[10]] of the Ministry of Ports, Shipping & Waterways, report stated that “the lack of infrastructure in the country due to the collapse of private shipyards, resulted in the erosion of capacity and no proper financing system became a big deterrent to attract the attention of the leading ship owners and market players”. While shipyards in China, South Korea, and Japan delivered 38.1, 24.8, and 22.5 million DWT of ships respectively in the year 2021[[11]], the Indian shipbuilding industry delivered a meagre 0.03028 million DWT (30.28 thousand DWT) [[12]] during 2020-21. To appreciate this issue, it is important to first examine the initiatives already taken by the Government of India (GoI) for the shipbuilding industry.

Govt of India’s Initiatives for Shipbuilding Sector

The Govt of India has taken several proactive initiatives to bolster the shipbuilding sector in the country and foster self-reliance. Notably, the Shipbuilding Financial Assistance (SBFA) [[13]] [[14]], approved in 2015, offers financial support to Indian shipyards through a 20 per cent grant based on the contract price or fair price for each vessel built, valid for ten years from 2016 to 2026. To further enhance opportunities for domestic shipyards, the Right of First Refusal policy mandates government agencies and CPSUs to prioritize Indian shipyards for vessel procurement or repairs until 2025, with certain guidelines facilitating small shipyards’ participation. Recognizing the strategic importance of shipyards, they have been granted infrastructure status [[15]], allowing access to flexible long-term project loans, lower interest rates from Infrastructure Funds, relaxed External Commercial Borrowings (ECB) norms, and infrastructure bond issuance for working capital needs. Moreover, the Standard Operating Procedures for Chartering of Tugs [[16]] and Procurement of Deep-Sea Fishing Vessels under the Pradhan Mantri Matsya Sampada Yojana (PMMSY)[[17]] aim to promote small and medium shipyards.

In line with the vision of self-reliance and promoting Indian tonnage and shipbuilding, the criteria for granting the Right of First Refusal (ROFR)[[18]] in chartering vessels have been revised. The preference is now given to vessels that are Indian-built, Indian-flagged, and Indian-owned, thus encouraging the use of Indian-flagged vessels and fostering the growth of indigenous shipbuilding capacity. The Public Procurement (Preference to Make in India) [[19]] policy, revised in 2020, discourages issuing global tender enquiries for public procurement of goods and services below the value of INR 200 crores. This move supports domestic shipyards by potentially increasing orders and promoting the “Make in India” initiative. An important factor contributing to escalated costs in Indian shipbuilding is the imposition of taxes and duties on input material used in Shipbuilding. To mitigate the cost disparity faced by Indian shipyards and foster the growth of the domestic shipbuilding industry, the Government of India has exempted customs and central excise duties on input material used in shipbuilding [[20]]. Furthermore, through amendments to the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code [[21]], the Government of India has expedited taking over (or is in the process) of several private shipyards (for example, Tebma Shipyard (Malpe) by CSL, the ongoing takeover of ABG Shipyard & Reliance Naval) that have been shut down for many years owing to financial distress.

Despite these comprehensive and forward-looking initiatives which demonstrate the Government’s commitment to creating a conducive environment for shipbuilding growth, the industry, as a whole, so far has not been able to fully capitalize on these initiatives. As of March 2023, reports [[22]] indicate that out of the substantial Rs. 4000 Cr corpus allocated for the Shipbuilding Financial Assistance Package, only a few Shipyards have been able to effectively leverage the subsidy, amounting to a mere Rs. 261 Cr. Looking back at the shipbuilding manufacturing discussed earlier, it becomes glaringly apparent that this predicament arises from the Shipbuilding Industry’s inability to attract large-scale commercial orders involving high DWT vessels (with the closure of high-capacity private shipyards, currently private shipbuilding is confined to small vessels), despite the support from Government and presence of domestic demand for ships.

Domestic Demand for Ships

As brought out in earlier reports [[23]], India’s overseas commercial shipping fleet has been predominantly foreign-controlled. Consequently, Indian flagged/controlled vessels account for only 8 per cent of the Indian export and import freight market. The fraction of Indian-flagged ships built domestically exposes the dearth of orders in the commercial shipbuilding sector. From various perspectives such as economy, trade, energy security, and shipbuilding, India must reduce its dependence on foreign-controlled and foreign-built ships for sea trade requirements. Another critical issue highlighted in the report pertains to the aging profile of India’s overseas fleet. Data reveals that over 50 per cent of the fleet, both in terms of number and gross tonnage, is over 15 years old, with nearly 35 per cent surpassing the 20-year mark. In contrast, the average age of the international fleet stands at 15.06 years. Consequently, at least 50 per cent of India’s existing overseas fleet would necessitate replacement in the next five to ten years.

It is important to note that as per the DG Shipping order [[24]], vessels over 20 years will not be allowed to operate in Indian Waters. On the coastal and inland waterways front, the Government has taken cognisance of their cost efficiency and the Sagarmala program targets an increase in the share of waterways to about 12 per cent by 2025. In FY19, coastal shipping accounted for about 120 million tons per annum (MTPA) of cargo transportation, and the GoI has targeted an increase to about 230 MTPA by 2025. Further, the Inland Waterways Authority of India (IWAI) has declared 111 rivers across the country as national waterways for cargo movement. To achieve this target and sustain this growth, it is estimated that India’s existing coastal and inland waterway fleet would need to be tripled in the next 5 to 10 years. This has the potential to create a shipbuilding demand of about 12.75 million Compensated Gross Tonnage (CGT). In the defence sector, as per the Maritime Capability Perspective Plan (MCPP), the Indian Navy’s goal to become a 170-ship force [[25]] by the end of this decade generates a substantial demand for defence shipbuilding.

The positive aspect to highlight is the persistent domestic demand for ships, which not only remains steadfast but is also predicted to experience substantial growth, offering a much-needed buffer between the Indian shipbuilding industry and global demand for ships. However, the private sector has yet to attain a competitive edge in the global market. Consequently, it becomes imperative for the industry to expeditiously rectify this situation. It is worth noting that, unlike other sectors, the expansion of shipbuilding not only influences the industry from a business point of view but also exerts a profound impact on the developmental aspects of the Indian economy.

Economic Impact of Shipbuilding

The Economic Survey [[26]] 2022-23 highlighted that the shipbuilding industry boasts a high employment multiplier of 6.48, indicating its capacity to generate a substantial number of job opportunities. Furthermore, the shipbuilding sector emerges as a potential solution to the issue of mass employment for migrating workers. As workers transition from traditional agricultural activities to more industrial settings, the shipbuilding industry can serve as a viable alternative to the construction sector, offering abundant job prospects and avenues for skill development. The economic implications of the shipbuilding industry extend beyond job creation, as it exhibits a notable investment multiplier effect. By employing a conservative Marginal Consumption to GDP Ratio (MCGR) of 0.45, the estimated investment multiplier is approximately 1.82. This implies that every unit of capital invested in shipbuilding stimulates economic activity and contributes to the growth of related industries. Such a multiplier effect is instrumental in driving India’s macroeconomic development. Moreover, the expansion of the shipbuilding sector fosters the development of Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs). The increased demand for ancillary products and services necessitates the growth of supporting industries, thereby promoting economic diversification and nurturing a culture of innovation and entrepreneurship.

This symbiotic relationship between the shipbuilding industry and MSMEs further strengthens India’s macroeconomic framework, making it more resilient and self-reliant, aligning with the vision of ‘Aatmanirbhar Bharat’. The shipbuilding industry’s contributions to employment generation, investment stimulation, and the growth of MSMEs make it a vital component of India’s economic fabric. By rising to the challenges, shipbuilding holds the potential to emerge as the vanguard of India’s growth narrative in the forthcoming years. Its ability to fulfill this role hinges upon a concerted effort from the industry players to bolster its competitiveness and seize the opportunities presented by the growing demand for ships both domestically and internationally. An unrelenting focus on innovation, quality, and efficiency will undoubtedly be key in positioning the Indian shipbuilding sector as a force in the global arena.

Challenges Faced by the Shipbuilding Industry in India

In a typical shipbuilding project, nearly 70-80 per cent constitutes material costs. Of this, about 30-40 per cent is steel cost which is sourced indigenously. Nearly 60-65 per cent [[27]] [[28]] cost is for electronics, engineering and electrical equipment. However, critical components like propellers, marine gas turbines, high-capacity main engines, shafting, gear boxes, high-capacity diesel generators, control systems, etc are mostly imported. Although Indian manufacturing exists for some of these items, their adoption has been limited. While the absence of domestic manufacturing capabilities is a problem for these items, dumping by foreign vendors at lower costs of some items is adversely impacting the domestic industry. The remaining 20-30 per cent constitutes labour and material overheads. As per studies [[29]], in India, the labour cost per worker is low and is of the order of $1,192 per year which is 10-20 times lower than the labour rates in the major shipbuilding nations. However, this low labour rate does not translate into lower ship costs, since the labour productivity is very low.

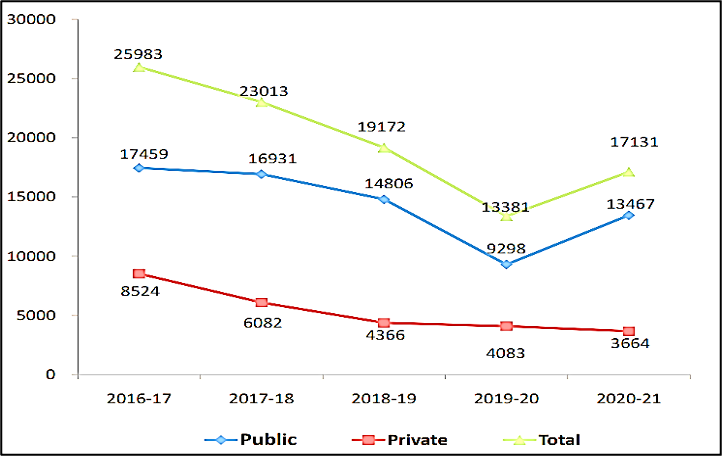

As per studies [[30]] the labour productivity value for India is approximately $11,134/employee and the values in South Korea and Japan are $1,22,994/employee and $1,51,487/employee respectively, i.e., approximately 10 times lower than the major shipbuilding nations. All these translate to about 20-25 per cent cost advantage for major shipbuilding nations vis-à-vis India. Another significant challenge faced by Indian shipbuilders is their relatively longer construction cycles. Unlike leading shipbuilding nations that construct vessels based on anticipated orders, Indian shipbuilders experience delays in design, planning, construction, and delivery, hindering their ability to meet market demands promptly. Additionally, the presence of a thriving resale market for ships in other Asian nations, such as China and South Korea, poses stiff competition for Indian shipbuilders. These countries offer vessels at significantly lower prices compared to new builds and even engage in the re-manufacturing of old ships to extend their operational life. Lastly, the diverse availability of a particular ship (like AHTS, PSV) at various price points globally creates a challenge for Indian shipbuilders to match the offerings present in the market, as different types of ships correspond to different quality levels. All these advantages lead to higher-order books in other countries which enable their shipyards to order all the material in bulk, which adds to cost advantage. These challenges faced by the Indian shipbuilding sector have significantly hampered its ability to fully capitalize on its high economic multiplier potential. This primarily translates into the dearth of substantial orders, which, in turn, has led to a noticeable decline in employment opportunities both in the shipbuilding and ship repair domains.

Figure3: Decreasing employment trend in Shipbuilding and ship repair in India

(Source: MoPSW [[31]])

Ship Financing

In addition to the aforementioned concerns, the domain of ship financing is fraught with intricate challenges that warrant examination. The issue of high working capital looms prominently in shipbuilding ventures during the construction phase, manifesting itself at around 20-25 per cent. [[32]]. Studies have also shown that there are instances where this figure is an even higher percentage of 35-40 per cent, signifying a heightened capital demand for certain classes of ships. [[33]] Typically, this requirement finds recourse in the form of bank loans, entailing a rather onerous financial burden. Recent studies indicate prevailing interest rates of approximately 10-10.5% for such loans, in stark contrast to the more favourable rates of 4-8% in major shipbuilding nations. [[34]] [[35]]

A further complexity is introduced by the cycles inherent in the shipping/ shipbuilding business. Regulations by central banks and evolving market dynamics necessitate that banks prioritise a robust debt-to-equity ratio exhibited by a prospective shipyard before extending financial support. This caution is uniformly exercised across banks. Comparable to the evolution of alternative financing avenues within sectors such as infrastructure and real estate, diversification within shipbuilding is equally conceivable. Mechanisms such as capital markets, structured finance, or direct lending could potentially foster an environment of sustained financial accessibility throughout the business cycle. In scenarios wherein the shipyard is a larger business conglomerate, securing requisite debt might happen with relative ease. However, the landscape changes distinctly for nascent start-up shipyards. In such instances, envisioning the establishment of a company, boasting an annual revenue of 150 Cr, would necessitate a capital infusion of approximately 200 Cr. Consequently, a significant portion, around 40-50 Cr, must be committed as equity – a collaborative manifestation of personal and partner funds. The residual sum, a substantial 150 Cr, must be sought in the form of debt, invariably supported by collateralized assets, including the vessel under construction.

Debt Financing:

This scenario engenders a debt-equity ratio of 4:1, or perhaps even more. This scenario contrasts starkly with the academically advocated preference of maintaining a 2:1 debt-equity ratio, an axiom advocated within business pedagogy. For those inclined to traverse higher-risk terrain, the spectrum might extend towards 2.5 or even 3. As the debt quotient escalates, so too does the onus of servicing interest obligations, potentially diverting entrepreneurial efforts towards debt servicing as opposed to substantive business expansion. Thus, a prudent fiscal posture encourages minimizing debt. Within capital-intensive domains like shipbuilding, instances of a 4:1 debt-equity ratio may not be unheard of. Yet, this milieu is characterised by meagre margins and the spectre of order scarcity, coupled with the latent risk of contract cancellations, collectively fostering an aversion to excessive debt within both banking and fund institutions. Further, it needs to be seen how the introduction of Basel-3 standards [[36]] for commercial banks by RBI would impact the leverage ratios w.r.t shipbuilding debt financing.

Equity Financing:

Consequentially, direct equity infusion assumes significance. Mutual funds have a restriction of 5-10 per cent NAV in unlisted equities [[37]], where most nascent private shipyards fall. Under such circumstances, avenues for recourse are limited to the formation of an Alternate Investment Fund (AIF). Venture Capital including Angel Funds and Infrastructure funds which fall under Category-1 AIFs [[38]] could be used to finance early-stage investments, especially when shipbuilding has now been given the infrastructure status. Whereas, the working capital needs could be financed through Category-2 AIFs like Private Equity (PEs) [[39]]. However, the viability of venture capital within the shipbuilding sector appears uncertain as of now, given the inherently capital-intensive nature of the industry and the less evolved shipbuilding ecosystem in India, which would not attract venture capitalists. On the other hand, the private equity option also comes with its attendant complexities. Private equity investors exact multifarious terms and stipulations, spanning assured returns and strategically devised exit mechanisms. It is a realm that demands a degree of confidence and resilience from an entrepreneur willing to navigate such terrain.

To tackle equity financing challenges within infrastructure projects, the Government of India took a significant step by establishing the National Investment and Infrastructure Fund (NIIF). This entity operates as an Alternative Investment Fund (AIF) functioning akin to a Quasi-Sovereign Wealth Fund (SWF). Its primary objective is to extend financial support to companies engaged in financing infrastructure projects that require long-term capital. NIIF offers an attractive avenue for private equity investors, presenting them with valuable investment prospects. Since Shipbuilding has been granted infrastructure status, NIIF could bring in several benefits. However, it’s noteworthy that NIIF currently does not encompass the shipbuilding sector. This omission could be attributed to the shipbuilding industry’s relatively nascent ecosystem and the inherent risks associated with it. As can be seen, there is no dearth of financial instruments for Ship financing. The challenge lies in attracting investment through them into Shipbuilding. But the only way to achieve this is to first de-risk the business itself and increase the productivity of the industry.

Ship Finance Leasing & Production Linked Incentive (PLI Scheme) for Shipbuilding

To achieve this, in addition to the existing initiatives, two potential interventions could be the adoption of a Ship finance leasing model and Production Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme, to improve the shipbuilding ecosystem in India. Such measures would not only de-risk the shipbuilding business and encourage efficient Shipyards but also would conform to the regulatory prescriptions of the World Trade Organization (WTO), thus fostering a harmonious confluence of economic pragmatism and international compliance.

Ship Finance Leasing

Ship finance leasing could be one of the solutions to the financing predicaments faced by prospective investors in shipping and shipyards in India. This financing model involves separating ship ownership from its usage rights. The shipowner gains ownership through purchase, while the shipping company or a charterer enjoys the ship’s usage rights through a lease contract. This approach addresses the capital turnover pressure experienced by shipping companies. Further, this model of financing reduces capital pressure on the shipyards also, on whom the shipbuilding contract is placed. As a result, the shipping company is derisked from owning a capital-intensive asset like a ship while the shipyard’s exposure to the risks emanating from Shipping operations, chartering, and freight markets is minimized to a great extent. As a result, it also opens up investment opportunities for potential investors through financial instruments [[40]].

Production Linked Incentive (PLI) Scheme

While the current initiatives by the GoI do effectively consider the macro-economic dimensions of the shipbuilding industry, there remains a need to address the productivity challenges intrinsic to the Indian shipbuilding sector. A potential Production Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme for the shipbuilding industry could encompass a range of incentives aimed at fostering growth and competitiveness. This scheme might involve output-based rewards, where shipbuilders receive incentives based on the quantity and type of ships they produce, encouraging higher production levels. Additionally, investment incentives could be granted to those who invest in modernising their facilities and adopting advanced manufacturing technologies. Quality and innovation could also be incentivised, promoting shipbuilders to create high-quality, innovative vessels that meet global standards. Export-oriented benefits could drive shipbuilders to manufacture ships for international markets, boosting the country’s presence in the global shipbuilding sector. The scheme might also offer rewards for generating employment opportunities, contributing to economic expansion. Encouraging energy efficiency and environmentally friendly practices could align with sustainability goals. Moreover, incentives linked to skill development, research and development, and transparent reporting mechanisms could further bolster the industry’s capabilities and accountability.

An important provision that merits consideration within this PLI scheme is the promotion of equipment manufacturing for Shipbuilding. Although this might initially seem ambitious, it’s important to acknowledge that the path to global competitiveness for Indian shipbuilders necessitates a departure from reliance on imported equipment. Furthermore, it’s crucial to recognize that if the Indian shipbuilding industry chooses to await the development of domestic equipment manufacturing capabilities, the industry will inevitably remain susceptible to the inefficiencies inherent in the equipment sector, predominantly the R&D ecosystem. This implies that no matter how enhanced the productivity of shipyards become, they would remain vulnerable to the limitations of the equipment industry. Crafting such a scheme requires careful consideration of industry dynamics and policy objectives to ensure its effectiveness and positive impact on the shipbuilding sector.

Conclusion

The crucial interplay between the shipbuilding industry, economic security, and strategic interests of India should be recognised. While the maritime sector remains a cornerstone of India’s trade and economic growth, the preponderance of foreign-built and controlled vessels poses significant challenges. The shipbuilding industry’s potential to drive economic development, create jobs, and foster innovation is evident, yet various obstacles hinder its full realisation. The Government of India’s initiatives to support shipbuilding demonstrates a commitment to fostering self-reliance and bolstering domestic capabilities. However, the industry grapples with complex challenges, including dependency on imported equipment, labour productivity, construction cycles, and competition from foreign shipyards.

Effective solutions demand a multi-pronged approach that involves fostering domestic manufacturing, enhancing productivity, and exploring innovative financing mechanisms. The proposed ideas, such as a Production Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme and ship finance leasing, hold promise in addressing the financial hurdles faced by shipbuilders. A PLI scheme could incentivize increased production, modernization, quality, and innovation, thus propelling the industry forward. Ship finance leasing, on the other hand, offers a potential remedy for the capital turnover pressure and de-risk the owners, shipbuilders, and shipping companies who could attract a wider range of investors. As India strives for self-reliance and aims to reduce its dependence on foreign-built and controlled ships, collaborative efforts between the government, industry players, and financial institutions will be crucial. The shipbuilding sector’s growth not only holds economic significance but also contributes to India’s strategic autonomy, ensuring a secure and resilient maritime trade infrastructure. In navigating the intricate waters of shipbuilding, economic security, and strategic aspirations, a comprehensive and adaptable approach is paramount. By fostering innovation, enhancing competitiveness, and embracing innovative financing models, India’s shipbuilding industry can truly set sail towards realizing its potential as a cornerstone of the nation’s economic growth and security in the maritime domain.

Disclaimer: Views expressed are of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Govt of India.

*****

*About the Authors

Admiral Karambir Singh (Retd.), was India’s 24th Chief of the Naval Staff. He is currently the Chairman of the National Maritime Foundation, New Delhi.

Commander Y Hemanth Kumar is posted at the Directorate of Naval Architecture, New Delhi. He is an Alumnus of Naval War College, Goa. He may be contacted at hemanthnavy@gmail.com.

References

- Mourougane, Dr. “Present Scenario of Ship Building Industry in India.” Journal of Development Economics, 2020. https://www.cdes.org.in/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Dr.-A.Mourougane.pdf.

- “Boats for Deep Sea Fishing.” PIB. March 29, 2022. https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1810959.

- Delvi, Anil. “Building an India Owner Merchant Fleet,” December 26, 2019. https://www.gatewayhouse.in/india-owned-merchant-fleet/#_ftn1.

- Division, Economic. “Half-Yearly Economic Review 2023-24.” New Delhi, 2023. https://dea.gov.in/sites/default/files/Half-Yearly Economic Review FY24_November 2023.pdf.

- “Shipbuilding : Productivity & Efficiency Benchmarking,” n.d. https://www.dsir.gov.in/sites/default/files/2019-11/9_9.pdf.

- Economic Survey. “Shipbuilding Sector: Achieving Self-Reliance and Promoting Make in India.” New Delhi, 2023.

- Securities and Exchange Board of India (Alternative Investment Funds) Regulations, 2012, The Gazette of India § (2012). https://www.sebi.gov.in/legal/regulations/jan-2023/securities-and-exchange-board-of-india-alternative-investment-funds-regulations-2012-last-amended-on-january-9-2023-_67273.html.

- Guidelines for Implementation of Shipbuilding Financial Assistance Policy, (2016-26), Pub. L. No. SS/MISC(15)/2015 (2016). https://www.dgshipping.gov.in/writereaddata/ShippingNotices/201607131104291790870shippingbuilding_financial_asstance_policy_04072016.pdf.

- Guidelines for Shipbuilding Financial Assistance Policy (SBFAP) – Amendment regarding., Pub. L. No. SY-16023/6/2015-SBR, Part-1, 43 (2021). https://shipmin.gov.in/sites/default/files/Amended guidelines.pdf.

- “IBBI Amends Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India Regulations, 2017.” PIB, June 15, 2022. https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1834292#:~:text=The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code,insolvency professional agencies and information.

- “SAFAL,” 2021. https://www.ifsca.gov.in/Document/ReportandPublication/safal-report-final-2021-10-28-signed-live1212112021032138.pdf.

- “Infrastructure Status to Shipyard Industry.” PIB, March 10, 2016. https://pib.gov.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=137711#:~:text=Infrastructure status would enable Indian,and invest in capacity expansion.

- “Inputs Used in Ship Manufacturing and Repair Exempted from Customs and Central Excise Duties.” PIB, December 1, 2015. https://pib.gov.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=132200.

- “Leveraging Defence Ship Building to Catalyse India’s Shipbuilding Industry,” 2020. https://www.npcindia.gov.in/NPC/Uploads/publication/Leveraging defence shipbuilding_LR371892.pdf.

- “Annual Report.” New Delhi, n.d. https://shipmin.gov.in/sites/default/files/Annual Report 2022-23 English.pdf.

- “First Advance Estimates of National Income, 2023-24.” PIB, 2024. https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1993550.

- Peri, Dinakar. “Navy on Course for 170 Ship Force: Navy Vice Chief.” Hindu, November 16, 2021. https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/navy-on-course-for-170-ship-force-navy-vice-chief/article37525244.ece.

- Rasmussen, Niels. “Chinese Shipyards Hit Record 47% Market Share in 2022.” February 15, 2023. https://www.bimco.org/news-and-trends/market-reports/shipping-number-of-the-week/20230215-snow#:~:text=In 2022%2C Chinese shipyards reached,Japanese and South Korean shipyards.

- Master Circular – Basel III Capital Regulations, Pub. L. No. RBI/2023-24/31 DOR.CAP.REC.15/21.06.201/2023-24 (2023). https://doi.org/10.4337/9781784719227.00011.

- Revised Consolidated Instructions regarding Global Tender Enquiry (GTE) rule 161 (iv) for General Financial Rules (GFRs), 2017 up to Rs.200 Cr- regarding., Pub. L. No. DPE/7(4)/2017-Fin. (2021). https://dpe.gov.in/sites/default/files/GTE-09-08-2021.pdf.

- “Rs 4,000 Cr State-Aid for Shipbuilding Go Abegging as Yards Collapse.” Economic Times, May 1, 2023. https://infra.economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/ports-shipping/rs-4000-cr-state-aid-for-shipbuilding-go-abegging-as-yards-collapse/99902559.

- Securities and Exchange Board of India (Mutual Funds) (Amendment) Regulations, 1999 (1999). https://www.sebi.gov.in/sebi_data/commondocs/CIRMF092000_h.html#:~:text=A mutual fund scheme shall,the NAV of the scheme.

- “Shipbuilding Industry Capable of Generating Mass Employment in Remote, Coastal and Rural Areas: Shri Mansukh Mandaviya.” PIB. November 25, 2019. https://pib.gov.in/Pressreleaseshare.aspx?PRID=1593424.

- Shipping, DG. DGS Order on Age Norms and Other Qualitative Parameters w.r.t Ships, Pub. L. No. F.No.16-17011/5/2022-SD-DGS (2023). https://www.dgshipping.gov.in/WriteReadData/News/202302270559032302259DGSOrder06of2023onAgeNorms.pdf.

- SOP for charter of tugs by Major Ports under Atmanirbhar Abhiyan Policy and Implementation of Public Procurement (Preference to Make in India), Pub. L. No. SY-13013/1/2020-SBR (2020). https://shipmin.gov.in/sites/default/files/To be uploaded on MOS Website.pdf.

- “India: Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) from September 2021 to September 2023,” n.d. https://www.statista.com/statistics/275297/purchasing-managers-index-pmi-in-india/.

- Wen, Xionghui. “Research on Financing Methods of China’s Shipbuilding.” Theoretical Economics Letters 08, no. 14 (2018): 3116–40. https://doi.org/10.4236/tel.2018.814194.

- Wing, Transport Research. “Statistics of India’s Ship Building and Ship Repairing Industry.” New Delhi, n.d.

Endnotes

[1]“Leveraging Defence Ship Building to Catalyse India’s Shipbuilding Industry,” 2020, https://www.npcindia.gov.in/NPC/Uploads/publication/Leveraging defence shipbuilding_LR371892.pdf.

[2] Niels Rasmussen, “Chinese Shipyards Hit Record 47% Market Share in 2022,” February 15, 2023, https://www.bimco.org/news-and-trends/market-reports/shipping-number-of-the-week/20230215-snow#:~:text=In 2022%2C Chinese shipyards reached,Japanese and South Korean shipyards.

[3] Anil Delvi, “Building an India Owner Merchant Fleet,” December 26, 2019, https://www.gatewayhouse.in/india-owned-merchant-fleet/#_ftn1.

[4] IFSCA, “SAFAL,” 2021, https://www.ifsca.gov.in/Document/ReportandPublication/safal-report-final-2021-10-28-signed-live1212112021032138.pdf.

[5] IFSCA, “SAFAL,” 2021, https://www.ifsca.gov.in/Document/ReportandPublication/safal-report-final-2021-10-28-signed-live1212112021032138.pdf.

[6] Economic Division, “Half-Yearly Economic Review 2023-24” (New Delhi, 2023), https://dea.gov.in/sites/default/files/Half-Yearly Economic Review FY24_November 2023.pdf.

[7] MoSPI, “First Advance Estimates of National Income, 2023-24” (PIB, 2024), https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1993550.

[8] Statista, “India: Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) from September 2021 to September 2023,” n.d., https://www.statista.com/statistics/275297/purchasing-managers-index-pmi-in-india/.

[9] Statista, “India: Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) from September 2021 to September 2023,” n.d., https://www.statista.com/statistics/275297/purchasing-managers-index-pmi-in-india/.

[10] MoPSW, “Annual Report” (New Delhi, n.d.),41. https://shipmin.gov.in/sites/default/files/Annual Report 2022-23 English.pdf.

[11]IFSCA, “SAFAL,” 2021, https://www.ifsca.gov.in/Document/ReportandPublication/safal-report-final-2021-10-28-signed-live1212112021032138.pdf.

[12] MoPSW, “Annual Report” (New Delhi, n.d.), 41. https://shipmin.gov.in/sites/default/files/Annual Report 2022-23 English.pdf.

[13]“Guidelines for Shipbuilding Financial Assistance Policy (SBFAP) – Amendment Regarding.,” Pub. L. No. SY-16023/6/2015-SBR, Part-1, 43 (2021), https://shipmin.gov.in/sites/default/files/Amended guidelines.pdf.

[14] “Guidelines for Implementation of Shipbuilding Financial Assistance Policy, (2016-26),” Pub. L. No. SS/MISC(15)/2015 (2016), https://www.dgshipping.gov.in/writereaddata/ShippingNotices/201607131104291790870shippingbuilding_financial_asstance_policy_04072016.pdf.

[15]“Infrastructure Status to Shipyard Industry,” PIB, March 10, 2016, https://pib.gov.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=137711#:~:text=Infrastructure status would enable Indian, and invest in capacity expansion.

[16] “SOP for Charter of Tugs by Major Ports under Atmanirbhar Abhiyan Policy and Implementation of Public Procurement (Preference to Make in India),” Pub. L. No. SY-13013/1/2020-SBR (2020), https://shipmin.gov.in/sites/default/files/To be uploaded on MOS Website.pdf.

[17] “Boats for Deep Sea Fishing,” PIB, March 29, 2022, https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1810959.

[18] “To Boost Shipbuilding in India , Ministry of Shipping Amends Right of First Refusal ( ROFR ) Licensing Conditions A Bold Step towards ‘ AatmaNirbharShipping ’ for ‘AatmaNirbhar Bharat.” PIB. New Delhi, October 2020. https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1666728.

[19] “Revised Consolidated Instructions Regarding Global Tender Enquiry (GTE) Rule 161 (Iv) for General Financial Rules (GFRs), 2017 up to Rs.200 Cr- Regarding.,” Pub. L. No. DPE/7(4)/2017-Fin. (2021), https://dpe.gov.in/sites/default/files/GTE-09-08-2021.pdf.

[20] “Inputs Used in Ship Manufacturing and Repair Exempted from Customs and Central Excise Duties,” PIB, December 1, 2015, https://pib.gov.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=132200.

[21] “IBBI Amends Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India Regulations, 2017,” PIB, June 15, 2022, https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1834292#:~:text=The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, insolvency professional agencies and information.

[22]“Rs 4,000 Cr State-Aid for Shipbuilding Go Abegging as Yards Collapse,” Economic Times, May 1, 2023, https://infra.economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/ports-shipping/rs-4000-cr-state-aid-for-shipbuilding-go-abegging-as-yards-collapse/99902559.

[23]“Leveraging Defence Ship Building to Catalyse India’s Shipbuilding Industry,” 2020. https://www.npcindia.gov.in/NPC/Uploads/publication/Leveraging defence shipbuilding_LR371892.pdf.

[24] DG Shipping, “DGS Order on Age Norms and Other Qualitative Parameters w.r.t Ships,” Pub. L. No. F.No.16-17011/5/2022-SD-DGS (2023), https://www.dgshipping.gov.in/WriteReadData/News/202302270559032302259DGSOrder06of2023onAgeNorms.pdf.

[25] Dinakar Peri, “Navy on Course for 170 Ship Force: Navy Vice Chief,” Hindu, November 16, 2021, https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/navy-on-course-for-170-ship-force-navy-vice-chief/article37525244.ece.

[26] Economic Survey, “Shipbuilding Sector: Achieving Self-Reliance and Promoting Make in India” (New Delhi, 2023).

[27] “Shipbuilding Industry Capable of Generating Mass Employment in Remote, Coastal and Rural Areas: Shri Mansukh Mandaviya,” PIB, November 25, 2019, https://pib.gov.in/Pressreleaseshare.aspx?PRID=1593424.

[28]“Leveraging Defence Ship Building to Catalyse India’s Shipbuilding Industry,” 2020. https://www.npcindia.gov.in/NPC/Uploads/publication/Leveraging defence shipbuilding_LR371892.pdf.

[29]DSIR, “Shipbuilding : Productivity & Efficiency Benchmarking,” n.d., https://www.dsir.gov.in/sites/default/files/2019-11/9_9.pdf.

[30]DSIR, “Shipbuilding : Productivity & Efficiency Benchmarking,” n.d., https://www.dsir.gov.in/sites/default/files/2019-11/9_9.pdf.

[31] Transport Research Wing, “Statistics of India’s Ship Building and Ship Repairing Industry” (New Delhi, n.d.).

[32]DSIR, “Shipbuilding : Productivity & Efficiency Benchmarking,” n.d., https://www.dsir.gov.in/sites/default/files/2019-11/9_9.pdf.

[33] Dr. A.Mourougane, “Present Scenario of Ship Building Industry in India,” Journal of Development Economics, 2020, https://www.cdes.org.in/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Dr.-A.Mourougane.pdf.

[34]DSIR, “Shipbuilding : Productivity & Efficiency Benchmarking,” n.d., https://www.dsir.gov.in/sites/default/files/2019-11/9_9.pdf.

[35] Dr. A.Mourougane, “Present Scenario of Ship Building Industry in India,” Journal of Development Economics, 2020, https://www.cdes.org.in/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Dr.-A.Mourougane.pdf.

[36] RBI, “Master Circular – Basel III Capital Regulations,” Pub. L. No. RBI/2023-24/31 DOR.CAP.REC.15/21.06.201/2023-24 (2023), https://doi.org/10.4337/9781784719227.00011.

[37] SEBI, “Securities and Exchange Board of India (Mutual Funds) (Amendment) Regulations, 1999” (1999), https://www.sebi.gov.in/sebi_data/commondocs/CIRMF092000_h.html#:~:text=A mutual fund scheme shall,the NAV of the scheme.

[38] GOI, “Securities and Exchange Board of India (Alternative Investment Funds) Regulations, 2012,” The Gazette of India (2012), https://www.sebi.gov.in/legal/regulations/jan-2023/securities-and-exchange-board-of-india-alternative-investment-funds-regulations-2012-last-amended-on-january-9-2023-_67273.html.

[39]GOI, “Securities and Exchange Board of India (Alternative Investment Funds) Regulations, 2012,” The Gazette of India (2012), https://www.sebi.gov.in/legal/regulations/jan-2023/securities-and-exchange-board-of-india-alternative-investment-funds-regulations-2012-last-amended-on-january-9-2023-_67273.html.

[40] Xionghui Wen, “Research on Financing Methods of China’s Shipbuilding,” Theoretical Economics Letters 08, no. 14 (2018): 3116–40, https://doi.org/10.4236/tel.2018.814194.

A View of Hindustan Shipyard Limited (Image Credit: www.reddit.com)

A View of Hindustan Shipyard Limited (Image Credit: www.reddit.com)

Credit: Google Earth

Credit: Google Earth

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!