China’s aggression in the South China Sea (SCS) has once again become evident, especially with recent images and videos showing Chinese Coast Guard personnel using crude weapons[1], roughly akin those used during the Galwan clash on India’s Northern borders in 2020, to intimidate Philippine supply missions to their outpost at the Second Thomas Shoal.

While there has been a lot of commentary on China’s actions in the SCS, it would be wise to re-examine and critically analyse the origin of the issue, the actions of some main players, and the lessons that can be learned, especially considering the increasing Chinese presence in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) and growing maritime competition with India.

Background

China’s rise on the global stage, if not yet as a “great” power, then at least as a “major” one, is undeniable. The implications of China’s rise are widely debated and closely watched. On the one hand, there is the widely expressed Chinese view that the country’s rise is benign[2] and purely economic, which justifies its increasing visibility and what others call aggression as simply a necessity to safeguard its trade and economic interests. On the other, there is the long-held view of China watchers and experts, especially in the Western strategic and intelligence community, that China and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) have hegemonic and revisionist ambitions. They believe that beyond just consolidating its power, the CCP seeks to reshape the existing world order according to what might be termed Chinese standards, values, and norms, and return China to a position of strength, prosperity, and global leadership[3].

Given the situation at the time and China’s relative weakness compared to the existing balance of power, China under Deng Xiaoping pursued its ambitions under the well-known dictum, “hide your strength, bide your time, never take the lead.” This approach is similar to George Washington’s advice to his countrymen to avoid “entangling alliances”, since these were just a means to an end and not the end itself. While China continued to build its strength under this dictum during the leadership of Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao, Xi Jinping, it seems, believed that the circumstances that restrained his predecessors had changed[4], and China was now ready to engage with the world from a position of strength. The rise of President Xi thus marks a point of inflection, where China’s approach and actions on the world stage, which unlike Russia, previously aimed to project a positive and benign image, have now become increasingly aggressive and confrontational.

Influence Operations

The primary manifestation of China’s aggression is in the form of what are increasingly being called ‘Influence Operations’. As the term suggests, Influence Operations are aimed at inducing or reinforcing desired attitudes and behaviour from the target, which could be an individual, a group, a country, a region, or even the entire globe. What sets Influence Operations apart from other means of conventional conflict is that these are ubiquitous and perpetually ongoing across the entire ‘DIME’ (Diplomatic, Information, Military and Economic) paradigm. The importance of Influence Operations in Chinese strategic thinking can be better understood through the highly regarded book “Unrestricted Warfare”[5] by two PLA colonels (who later became Generals). The book suggests the continuous and simultaneous use of all means, both military and non-military, lethal and non-lethal, to compel an adversary to accept one’s interests.

The “Three Warfares”. The “Three Warfares” doctrine, formulated in 2003, includes “public opinion (media) warfare”, “psychological warfare”, and “legal warfare” (lawfare). This doctrine outlines the core of China’s political warfare in both war and peace[6] and is likely the most common means of exerting influence.

This article will examine China’s use of “Lawfare” in the maritime domain, mainly in the South China Sea (SCS). It will also analyse the US reaction to ongoing Chinese aggression in this region and attempt to draw lessons for India, as well as suggest potential courses of action.

The Territorial Conflict in the South China Sea

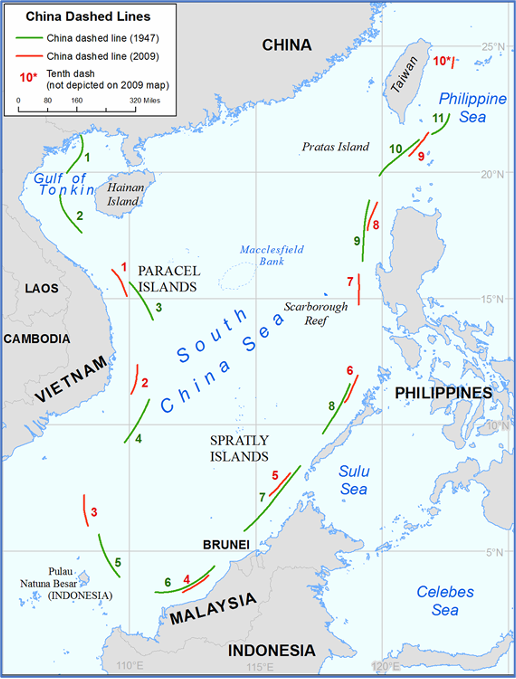

The Nine Dash Line. It is well known that China has promulgated a “nine dash line” that covers almost 85% of the South China Sea (SCS) (there are varying estimates in contemporary literature). What is perhaps less known is that the first instance of such lines appearing in popular discourse was through a map entitled, “Map of South China Sea Islands,” published in 1947 by the Nationalist Government of the Republic of China. Further research indicates that this map was based on another one entitled, “Map of Chinese Islands in the South China Sea” (Zhongguo nanhai daoyu tu), published in 1935 by the Republic of China’s Land and Water Maps Inspection Committee. The 1947 map had eleven dashes. The maps published by the People’s Republic of China (PRC) simply followed these older maps. However, PRC maps, based on a rapprochement with communist Vietnam, removed the two dashes that were earlier depicted within the Gulf of Tonkin, thus showing nine dashes instead of eleven[7]. Modern Chinese maps published since 1984, have been depicting a 10th dash, located to the east of Taiwan.

Figure 1: Comparison of Dashed Line in 2009 and 1947 Maps

Source: US Dept of State – China: Maritime Claims in the South China Sea[8]

Opposition to Chinese Claims. While China may have believed that the above maps were generally accepted by the other coastal States of the region, what disrupted this assumption was a joint submission by Vietnam and Malaysia on 06 May 2009, to the “Commission on the Limits of Continental Shelf” (CLCS), claiming an extended continental shelf in the southern part of the SCS. This was followed by a separate submission by Vietnam in the area north of its joint submission with Malaysia. Malaysia then indicated that it too would be making a partial submission in the same area as Vietnam. While the Philippines did not make a separate submission at that time, it officially informed the CLCS that the submissions of both Vietnam and Malaysia overlapped the legal continental shelf of the Philippines.[9] The positions taken by these three ASEAN States presented a serious challenge to China’s prospective use and exploitation of resources in the area. On 07 May 2009, within a day of the above-mentioned joint submission, China submitted two Notes Verbale (NV) to the UN Secretary General stating:

“China has indisputable sovereignty over the islands in the South China Sea and the adjacent waters, and enjoys sovereign rights and jurisdiction over the relevant waters as well as the seabed and subsoil thereof (see attached map). The above position is consistently held by the Chinese government and is widely known by the international community.”

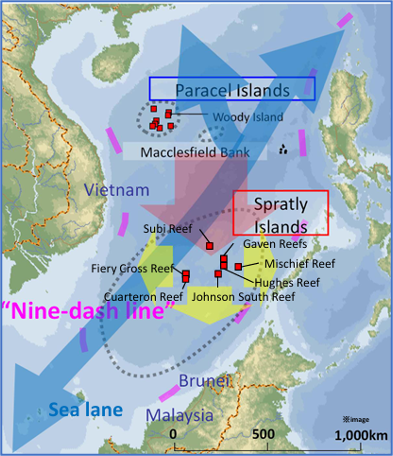

Figure 2: China’s Dashed-Line Map from Notes Verbales of 2009

Source: US Dept of State – China: Maritime Claims in the South China Sea[10]

This was the first time that the ‘Nine Dash Line’ map, encompassing approximately two million square kilometres of maritime space, was submitted to the UN by China. This led to a series of protests from the three ASEAN countries mentioned earlier, and from Indonesia as well. China responded to these protests with another NV[11] on 14 April 2011, which reiterated the first sentence of the 2009 NV above and added:

“China’s sovereignty and related rights and jurisdiction in the South China Sea are supported by abundant historical and legal evidence.”

It would be appropriate to consider the above sequence of events as the “reference timeframe” of the commencement of the territorial conflicts in the SCS as we know them today.

Inconsistencies in the Chinese Position. China has never clarified the legal basis or nature of its claims, nor has it published any geographical coordinates for the nine (or ten) dashes. Additionally, there are recurring geographical inconsistencies in the position and depiction of the dashed lines among the various maps published, first by the ROC, and later by the PRC. As a result, it is very difficult to determine a conclusive figure or estimate of Chinese claims in the SCS. Another area of contention is that these dashes are much closer to the mainland coasts and coastal islands of the littoral States of the SCS than to the SCS islands over which China claims sovereignty. For instance, “Dash #3” is 75 nautical miles from the closest Indonesian island, Pulau Sekatung, but almost 235 nautical miles from the Spratly Island.[12]

Figure 3: Distances between Dashes and Land Features

Source: US Dept of State – China: Maritime Claims in the South China Sea[13]

Contradictory Claims. All the island groups in the SCS have multiple claimants, with overlapping maritime zones and legal continental shelves (in accordance with UNCLOS). For example, China, Taiwan, and Vietnam, each claim the entire Spratly group of islands, with portions also being claimed by Malaysia and the Philippines. Brunei claims a legal continental shelf overlap and an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) one, over the Spratly group.[14]

UNCLOS. While this article does not intend to undertake a detailed analysis of Chinese claims, it is important to highlight a few (among many) inconsistencies that severely challenge the accepted legal regime put forth by the LOS Convention. The following are relevant:

(a) A majority of the ‘dashes’ fall within 200 nautical miles of the coasts of other littoral States in the region.

(b) As mentioned earlier, Chinese sovereignty over land features is severely contested, requiring the mutual delimitation of overlapping and contested maritime boundaries.

(c) For an island to be legally recognised as such, it should be above water at high tide. While an island has the same entitlement to maritime zones as other coastal territory, a rock that cannot sustain human habitation or economic life on its own is not considered an island and is only entitled to a territorial sea and a contiguous zone, but not an EEZ or legal continental shelf.[15] On the other hand, a low tide elevation (LTE) that lies wholly outside the territorial sea of the State concerned is only entitled to a 500-metre “safety zone”. Most land features in the SCS do not qualify as islands.

(d) The burden of establishing a historical claim lies with the claimant. The United States, based on the views of influential international legal authorities such as the International Court of Justice, and a study on Historic Waters and Bays commissioned by the Conference that adopted the 1958 Geneva Conventions on the law of the sea, has taken the view that for a historic claim to be valid, the claimant should have been exercising effective and continuous authority over the body of water in question, and there should have been acquiescence by other states in the exercise of that authority.[16] China clearly does not meet the necessary conditions of either having exercised continuous authority or acquiescence by other countries.

China’s Artificial Islands

“If the facts are against you, argue the law. If the law is against you, argue the facts. If the law and the facts are against you, pound the table and yell like hell”.[17]

Carl Sandburg

American Poet and Writer

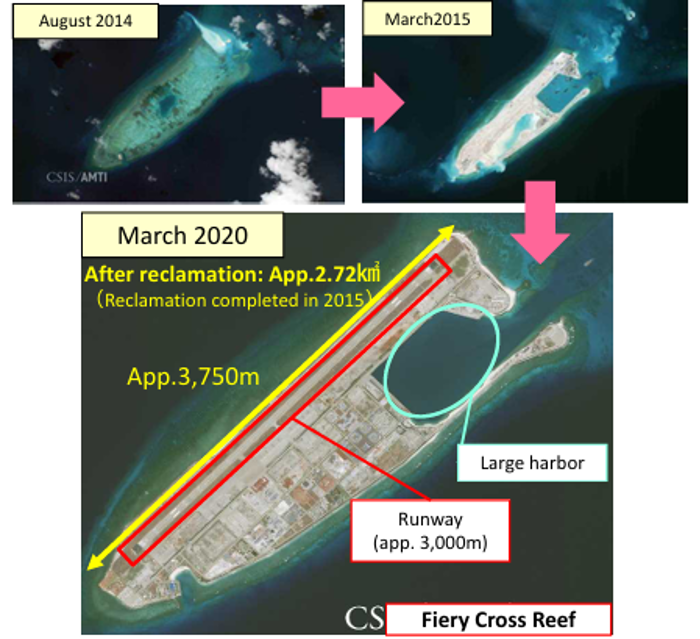

China’s Outposts in the Spratly Islands. The above adage perfectly reflects Chinese actions. While China has been advising all coastal States in the region to maintain peace, it has been busy pouring sand in the SCS. In 2013, China began dredging sand from the sea floor and dumping it on rocks and low-tide elevations in several of the Spratly islands. Between December 2013 and October 2015, China built artificial islands and outposts covering about 3,000 acres on seven coral reefs in the southern part of the SCS[18], namely, Fiery Cross, Mischief, Subi, Cuarteron, Gavin, Hughes, and Johnson reefs.

Figure 4: China’s Artificial Islands

Figure 4: China’s Artificial Islands

Source: Japan Ministry of Defence[19]

Amongst these, Fiery Cross, Mischief, and Subi reefs are particularly significant as these outposts now host substantial Chinese military infrastructure such as runways and helipads, naval port facilities, surveillance radars, air defence and anti-ship missiles, and troops.[20] However, contrary to popular belief, it is not only China that has reclaimed and fortified features in the Spratly Islands. Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan, and Vietnam all occupy features that have been developed into outposts with military infrastructure, and some have also undertaken reclamation activities. The scale, on the other hand, is vastly different. While China reclaimed over 3,000 acres in about eighteen months, the other four countries together reclaimed less than 150 acres in the same period.[21] The US response to these activities was muted at best, possibly recognising that a sovereign country is the highest entity in the international legal system, and Washington did not distinguish between Chinese efforts and those of the other coastal states in the SCS.

Figure 5:Chinese Reclamation on Fiery Cross Reef

Source: Japan Ministry of Defence[22]

“Lawfare” Related Implications of Chinese Reclamations in the SCS

While the artificial islands in the SCS provide China with geostrategic benefits such as platforms for power projection, a potential deep-water bastion for nuclear submarines, and a permanent foothold in a vital waterway, what may be even more important is the strengthening of China’s claim to territory, rich seabed resources, and fisheries in the Spratly Islands. It is widely believed that China aims to assert its de facto sovereignty in the region and also strengthen its claim to the EEZ adjoining its coastline and all its islands in the SCS, under the aegis of UNCLOS.[23] Another conclusion that could be drawn is that China believes that, over time, its presence on the seven outposts in the Spratly group of islands will get normalised, resulting in the fulfilment of the two necessary conditions — “effective and continuous authority, and acquiescence by other states” — for acceptance of its historical claims. Chinese claims would then not only enjoy de facto but also de jure recognition.

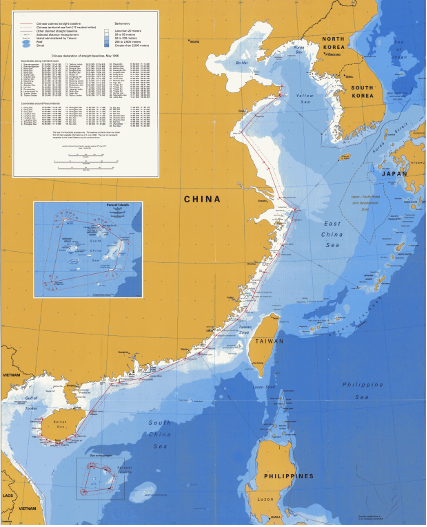

Excessive Chinese Maritime Claims. Claims in the SCS, combined with some of China’s national laws (whose legality is in question), provided the foundation for asserting additional maritime rights that are problematic from a legal standpoint. These are primarily of three types: prior authorisation or notification for warships to exercise innocent passage, prohibition of military activities in the EEZ, and the drawing of straight baselines even when geographic conditions for doing so are not satisfied.[24] According to the US Department of State, Bureau of Oceans and International Environmental and Scientific Affairs, the illegal use of straight baselines has resulted in sea areas of more than 3,190 square nautical miles and 1,150 square nautical miles being wrongly classified as “territorial sea” and “internal waters”, respectively, instead of their correct classification as “high seas”. Further, large areas have been classified as “internal waters” that should be categorised as “territorial sea”. Also, the use of archipelagic straight baselines around the Paracel Islands has resulted in China incorrectly claiming a huge sea area that should have been classified as “high seas” as “internal waters”. The low-water line of the islands and reefs therein ought to have been used to form the correct baseline.[25]

Figure 6: China’s claimed Straight Baselines

Source: US Dept of State, Bureau of Oceans and International Environmental and Scientific Affairs

US Response

The power differential between China and the other states in the SCS is simply too large for the latter—either individually or even collectively—to influence China’s intentions and actions. This, along with the strategic importance of the region and the heavy reliance of Taiwan, South Korea, the Philippines, and Japan on the US security umbrella, has made the US the de facto net security provider of choice in the SCS. Thwarting Chinese designs and aggression in the SCS is not feasible without active US involvement. Therefore, the US stance and response thereto regarding increasing Chinese assertiveness (as described in previous sections) in the SCS, merit examination.

Since the 1990s, the US has held to the belief that as China became more powerful and prosperous, it would, in its own interest, willingly accept and adopt the international rules-based order. The intent, in the words of US Deputy Secretary of State Robert Zoellick, in 2005, was to mold China into “a responsible stakeholder”.[26] The continuation of this aspect of US foreign policy was further exemplified by then US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s statement in Beijing in September 2012 that “our two nations are trying to do something that has never been done in history, which is to write a new answer to the question of what happens when an established power and a rising power meet”.[27] This obviously referred to the implications of shifting power dynamics in the international system and the danger of falling into “the Thucydides Trap”.[28]

Continuing this policy, US President Barack Obama, during a joint press conference with President Xi Jinping in September 2015, stated, “the United States welcomes the rise of a China that is peaceful, stable, prosperous, and a responsible player in global affairs”.[29] However, neither the US nor any of its allies, or any international construct for that matter, clarified the consequences should China choose not to live up to the western concept of a “responsible nation”. It may be surmised that the predominant American intent at that time was to avoid conflict. As a result, every time China violated its “rules-based order” obligations, the US took steps to de-escalate the situation and reduce tensions, essentially allowing China to continuously make incremental gains,[30] much like the practice of “salami slicing” on India’s Northern borders. Would it then be out of order to state that “US risk-aversion” laid the foundation for the current situation — with China on the cusp of near-total control over the SCS?

Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPS)

US Freedom of Navigation (FON) operations began in the post-World War II period, which saw the birth of several new coastal States and an increasing number of maritime claims. This was especially relevant in the 1960s and 1970s, when even States that had traditionally defended free seas began to view the “oceans as a resource rather than as the world’s highways”. The FON program was established in 1979 to preserve US navigational freedoms and demonstrate non-acceptance of excessive maritime claims by coastal states.[31]

China and the US have fundamental differences regarding UNCLOS. While the US, backed by precedence and the support of most nations, has long advocated for open seas with a focus on maritime sovereignty, China has interpreted UNCLOS far more restrictively and selectively, especially regarding the operations of foreign military vessels in its territorial sea and EEZ. Although the US was alarmed by China’s artificial islands, it was legally constrained (or had constrained itself) from contesting Chinese actions since they were technically not prohibited by UNCLOS. It can also be assumed that the US, to avoid escalating tensions, was reluctant to conduct FONOPS at this stage. However, US concerns about excessive Chinese maritime claims were confirmed when a US P-8 patrol aircraft in May 2015, even though operating more than 12 nautical miles from one of the artificial islands in the Spratly group, was ordered to leave China’s “military alert zone” (a term without any legal standing) by the PLA, thus providing the required rationale and urgency for FONOPS.[32]

The world has become accustomed to US FONOPS over the years. This raises the question of why this subject requires further discussion. However, analysing the first few FONOPS missions is important for assessing whether more could have been done to thwart increasing Chinese aggression and what lessons India and the world should draw.

FONOP on 27 October 2015. The first FONOP after the construction of the artificial islands under discussion was undertaken on 27 October 2015, by an Arleigh Burke Class guided-missile Destroyer, the USS Lassen, which transited within 12 nautical miles of Subi Reef (and also a few features claimed by other countries). It is important to highlight that Subi Reef is an artificial island built on a low tide elevation, and as such, is not entitled to UNCLOS-defined maritime zones, other than a safety zone of 500 metres. An analysis of the ship’s transit indicates that it was the US intention to assert its right of innocent passage without prior notification, thus opposing China’s demand for the latter. However, innocent passage is a concept relevant only to the territorial sea. Thus, by claiming innocent passage, the ship effectively gave credence to the assumption that Subi Reef was entitled to a territorial sea. Many US experts at that time believed this could be used by China in the near future to claim a ‘territorial sea’ around Subi Reef,[33] something China had avoided doing thus far. Considering China’s tendency to ‘creep forward,’ it is not overly imaginative to suggest that over time, China could even claim the status of an “island” for Subi Reef, with its own contiguous zone and an EEZ. Should the USS Lassen have undertaken manoeuvres and activities that are prohibited by UNCLOS within the territorial sea, is a question that then assumes significance.

Issues of Legality

Status of Subi Reef. As mentioned above, Subi Reef is a Low Tide Elevation (LTE). According to UNCLOS, the low tide mark of an LTE, which is situated wholly or partially within 12 nautical miles of the mainland or an island, may be used as the baseline for measuring the breadth of the territorial sea[34] — in other words, it may be used to ‘extend’ the territorial sea of the main or parent feature. In this case, Subi Reef is situated within 12 nautical miles of a feature called Sandy Cay and could be assumed to have a 12 nautical mile territorial sea, generated by Sandy Cay.

Analysis of the First FONOPS. Considering the above, one could argue that since the US recognised that Subi Reef lay within a legal territorial sea, the intent of the FONOPS was not to challenge the existence of the territorial sea but to exercise freedom of navigation in accordance with UNCLOS.[35] However, a few issues merit examination. First, Sandy Cay is a rock and not an island. Its territorial sea cannot be used under the ‘bump out’ provision in relation to Subi Reef. Secondly, for Subi Reef to have a territorial sea, both Subi Reef and Sandy Cay (the parent feature) would need to be legally possessed by the same country since the maritime entitlements of one country cannot be used to generate entitlements for another country. Here, Sandy Cay was (and is) unoccupied and was claimed by China, the Philippines, Taiwan, and Vietnam. Thirdly, as per Article 3 of UNCLOS, a territorial sea must be established. It requires affirmative action and is not automatic. None of the affected states, including China, have ever established a territorial sea in the Spratly Islands. Analysing US actions, it can be theorised that China’s intentional use of confusion and ambiguity over its claims ended up tying the US in legal knots and wrangles[36], resulting in a substantial dilution of the initial intent of the mission. An issue that perhaps requires deliberation is whether there was a lack of clarity amongst US planners regarding UNCLOS, while planning this important FONOPS.

US Neutrality. An assessment of US actions in the aforementioned sections brings to light a concerted effort to stay neutral in the SCS, whether it be by transiting during its FONOPS within 12 nautical miles of features claimed by other coastal States of the SCS, or in its response (or lack thereof) to the reclamation efforts by China and these other States. However, in terms of economic power, industrial capability, and military strength, there existed a vast difference between China and the other coastal states of the SCS, individually and even collectively. Such a rigid interpretation of neutrality or equality by the US severely disadvantaged the other SCS coastal States and has, today, put them, along with other stakeholders and the US itself, in a very difficult position.

Equality Amongst Equals. The Supreme Court of India has consciously avoided interpreting the equality clause laid down in the Indian Constitution in its literal meaning. Instead, in many judgments, the Hon’ble Supreme Court has upheld the principle of “relative equality” that promotes equality amongst equals. The Court has even stated that “to treat unequals differently according to their inequality is not only permitted but required”.[37] While it may be debated whether this provision and interpretation of jurisprudence could be applied to the international legal system, there is probably no better example of inequality than in the SCS. Should the US then, as the preeminent broker of security in the region, have exercised “affirmative action,” as it does so resolutely at the domestic level?

Increasing Chinese Presence in the IOR

China has significant interests in the Indian Ocean. Even though China is considered an rank outsider in this sub-region of the Indo-Pacific, it does have close and longstanding relations with many coastal States in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR). In fact, unlike the traditional powers of the IOR, China is the only country in the world that has an embassy in all six island countries in this region: Sri Lanka, Maldives, Mauritius, Seychelles, Madagascar, and Comoros.[38] China has also emerged as a credible security and economic partner across large parts of the IOR, including in Africa. Its much-discussed “Belt and Road Initiative” (BRI) has increased China’s footprint and influence and has enabled it to make strategic inroads into many IOR countries. Overall, China enjoys a perceptual benefit that has come mainly at the expense of the traditional global power, the United States,[39] and given the disruptive impact of China’s role in India’s immediate neighbourhood, some would say, at the expense of India as well.

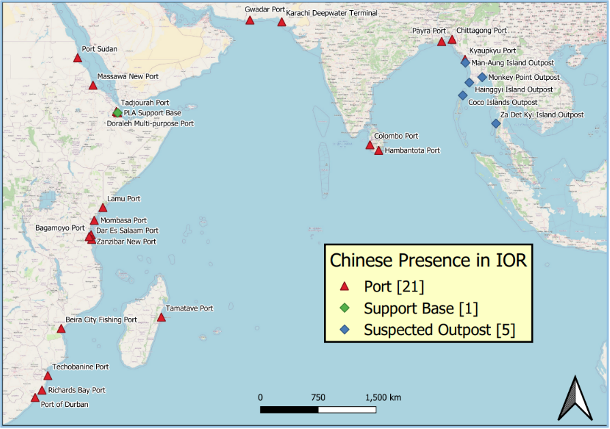

The Indian Ocean is China’s main trading route with Europe, Africa, the Middle East, and South- and Southeast Asia. It is no surprise that China’s first overseas logistic base was established in Djibouti. In pursuit of its geoeconomic and non-geoeconomic goals, China has been constantly increasing its military (PLAN) presence in the IOR since 2008, including creating dual-use infrastructure. In addition to its listening outposts, mainly in Myanmar, it is estimated that China has financed, built, and/or operated more than 21 ports in the IOR.[40]

Figure 7: Chinese Presence in the IOR

Source: ORCA[41]

Given New Delhi’s strained relationship with Beijing, especially after the 2020 developments on India’s northern borders, China’s increasing maritime presence in the IOR is a cause for considerable concern. This is even more relevant since all of India’s maritime neighbours are economically fragile and are under heavy Chinese debt (and hence influence). Of these, while Pakistan is openly hostile to India, the attitude of some of the others fluctuates according to the government in power.

Lessons from the SCS and What India Could Do

Although the geography of India’s maritime neighbourhood and China’s direct influence therein is quite different from that in the SCS, there are several similarities, too. Are there lessons from the SCS that could be applied in the IOR?

Procrastination is not an Option. China’s disruptive and damaging influence in India’s maritime neighbourhood is likely to be a long-term issue. As in the SCS, ‘lawfare’ will play a major role in China’s attempts to change the status quo in its favour. The current situation in the SCS can be partly attributed to a delayed response to Chinese activities. Even benign Chinese activities thus need to be seen from a long-term perspective in terms of whether these could at some stage disturb the existing normal. In addition to affirmative action across the entire DIME paradigm along with, if required, actions that visibly leverage India’s relative advantage (geographical and naval capability) in the IOR, these then need to be called out at the earliest and repeatedly thereon, at all the relevant multinational institutions and fora.

Although most of India’s maritime boundaries, other than with Pakistan (especially near the Sir Creek area), are adequately delineated (maritime boundaries cannot be demarcated), overlapping interpretations and interests with other coastal states, especially regarding the EEZs, are always a possibility. This is especially relevant since with several of these littorals, including Indonesia, there are EEZs that are demarcated based on the median lines/ historical waters principles.

Figure 8: Exclusive Economic Zone of India

Source: Wikipedia[42]

Clear Enunciation of Red Lines. In the above situation, China’s reclamation and construction of an artificial feature on an LTE within 12 nautical miles of either the mainland or an island of any of India’s maritime neighbours could, due to the applicability of the “bumping out of the territorial sea principle” result in a significant reduction of the Indian EEZ. In certain areas, such as the Coco Islands, this could give China a strategic advantage. The surreptitious construction of an LTE where none exists, and its development into an artificial structure, or the development of an artificial structure toward the extremities of the EEZ, in a position where it could provide an operational advantage (for example, close to Minicoy), are entirely feasible scenarios. While India might not be able to conduct detailed hydrographic surveys in such areas, a sharp lookout must be kept for any signs of such possibilities. Calling out such attempts along with increased presence in the area could have sufficient deterrent value. While sharp power could be used in a graded manner for strategic posturing (to deter China), it may be more effective to clearly and unambiguously indicate India’s red lines to the maritime neighbour in question. Starting with diplomatic engagement, progressing to economic nudging (or the possibility thereof), and even military posturing if required, supported by an effective information campaign that clearly conveys India’s intent, would likely achieve the desired results.

Strengthening Legal Expertise and Coordination. Another lesson from the US actions in the SCS is the dangers of an inadequate appreciation and application of UNCLOS. The 27th October 2015 FONOPS was probably planned and conducted in a hurry (due to the P-8 incident) without adequate focus on legal issues. China’s propensity for ‘lawfare’ makes close coordination between operational planners and legal experts mandatory. This is even more relevant now that the BBNJ Treaty will soon come into force. The time has come for the Government of India to establish a dedicated legal cell that specialises in maritime law and works closely with the various maritime law enforcement agencies, including in the planning of operations.

Countering the Use of Chinese Names. Although this has not been discussed in previous sections, a tactic of growing importance used by China in incrementally asserting its claims is assigning Chinese names to disputed features. China has used this tactic to support its contention that the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh is disputed and is part of South Tibet, and thus belongs to China. In 2018, China assigned standard names to twenty-five islands and reefs as well as fifty-five undersea geographic entities in the SCS in a move widely hailed in China for reaffirming sovereignty in the region.[43] China has now assigned names to nine seabed features in the Indian Ocean. While this is currently projected as a symbol of soft power, the use of these names to make historical claims later cannot be discounted. India would do well to follow such events closely and counter Chinese narratives by assigning its own names and reinforcing the correct historical perspective.

Narrative Building. It is vital to counter Chinese narratives from the initial stages with a strong and dynamic counternarrative. It would be prudent for India to establish a formal and dedicated structure that closely follows and analyses Chinese actions and their implications, especially those with the potential to be used for ‘lawfare’ and integrate this into an effective information-management structure. This structure should disseminate the correct perspective and dynamically adjust the counternarrative, especially in the maritime domain.

Visibly Resolute Response. The Indian experience on its northern borders and an examination of events in the SCS over the past decade indicate that China views the exercise of restraint and efforts to de-escalate by others as signs of weakness and opportunities to strengthen its own position. While the coastal States of the SCS may not be able to aggressively counter Chinese provocations (due to the power differential), relatively stronger countries such as India, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and obviously the US, need to put in place suitable deterrent measures. These could include joint SOPs, collective economic measures, increased presence in areas of concern, and joint information and diplomatic campaigns. Such posturing in and of itself would have substantial deterrent value.

There is No Substitute for Friends. China’s main disadvantages are its maritime geography and the fact that when it looks out seawards, it finds very few friends. These, along with China’s assertive tendencies, are the perfect recipe for isolation in the international order. New Delhi needs to leverage these strategic weaknesses, and the geographical advantage India enjoys in the Indian Ocean, by strengthening regional trust and synergy through enhancing the effectiveness of constructs such as BIMSTEC and IORA; developing a strategic relationship with ASEAN, including in the security domain; and leveraging opportunities provided by the Quad, IONS, and the MILAN series of engagements. In this context, India’s reassertion of it full acceptance of the 2016 award of the Arbitral Tribunal[44] in favour of the Philippines, during the recently concluded Quad Foreign Ministers Meeting in Tokyo on 29 July 2024, is extremely relevant.[45]

Maritime Militia. While this article does not intend to detail the concept and functioning of China’s “Maritime Militia”, also called the “People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia” (PAFMM), the issue merits mention due to its frequent use by Beijing to strengthen Chinese maritime claims. The PAFMM comprises two main categories: (1) at least a hundred purpose-built boats that look like fishing vessels, and (2) actual fishing boats drafted into China’s missions. These assets routinely intrude into foreign EEZs, block access to disputed reefs and islands, and conduct dangerous manoeuvres, including in the vicinity of naval vessels.[46] The PAFMM often serves quasi-military missions such as “presence”, and enforces the Nine Dash Line. China maintains a large number of research and survey vessels and a significant fishing fleet (500 to 600 vessels) in the IOR, all of which can have dual utility. Taking a cue from the Philippines, India must start calling out and publishing suspected activities of these vessels that are beyond normal. It may be prudent for the IFC-IOR, in conjunction with other regional IFCs, to start including a section on the PAFMM in their periodic reports.

The Burden of History. Finally, and at the risk of repetition, the two necessary conditions for the validity of historical claims — “effective and continuous authority, and acquiescence by other States” — in view of China’s propensity to twist history to its advantage, bear reiteration. India is surrounded by small countries in several of which China enjoys pervasive influence that is damaging to India. India must, therefore, always remain conscious of these two necessary conditions and take timely and continuing action to ensure these conditions are not met.

Conclusion

China’s geostrategies devised to pursue Beijing’s geoeconomic and non-geoeconomic goals require access to the Indian Ocean. While this may seem logical at first glance, China’s tendency to view the oceans in territorial terms is disconcerting to say the least. The India-China relationship, even at its best, is an uneasy and brittle one, and currently, it is openly hostile. In this context, China’s disregard for the “rules-based order”, its increasing assertiveness, the rapid expansion of its navy, and its undue influence in India’s maritime neighbourhood, make its growing presence in the Indian Ocean uncomfortable.

This article has analysed Chinese actions in the South China Sea, particularly its use of “lawfare”, and the effectiveness or lack thereof of the responses from other actors involved. The aim has been to draw lessons and make recommendations relevant to India.

******

About the Author:

Captain KS Vikramaditya is a serving officer of the Indian Navy, currently on appointment to the National Maritime Foundation, where he is a Senior Fellow. His research interests are wide and varied and he supplements his formidable academic credentials with his perspectives as an experienced practitioner. His present research focus is on the manner in which India’s own maritime geostrategies are (or are likely to be) impacted by those formulated and executed by the People’s Republic of China. He may be contacted at: indopac10.nmf@gmail.com

Endnotes:

[1] Bidisha Saha, Subham Tiwari and Aakash Sharma, “In visuals: China does a Galwan against Philippines in South China Sea”, India Today, 21 June 2024. https://www.indiatoday.in/world/story/china-does-a-galwan-against-philippines-in-south-china-sea-visuals-2555951-2024-06-20.

[2] Embassy of the PRC in India, “Chinese Modernisation: Peaceful Development”. http://in.china-embassy.gov.cn/eng/xzjx/202309/t20230924_11148874.htm.

[3] US DoD, “Military and Security Developments involving the People’s Republic of China – 2020”, Annual Report to Congress. https://media.defense.gov/2020/Sep/01/2002488689/-1/-1/1/2020-DOD-CHINA-MILITARY-POWER-REPORT-FINAL.PDF.

[4] Paul Rahe, “Defending Taiwan”, Strategika, June 6, 2022. https://www.hoover.org/research/defending-taiwan-0.

[5] Qiao Liang and Wang Xiangsui, “Unrestricted Warfare”, Beijing: PLA Literature and Arts Publishing House, February 1999. https://www.c4i.org/unrestricted.pdf.

[6] P. Charon and J.-B. Jeangène Vilmer, “Chinese Influence Operations: A Machiavellian Moment”, Report by the Institute for Strategic Research (IRSEM), Paris, Ministry for the Armed Forces, October 2021. https://www.irsem.fr/report.html.

[7] Study by Office of Ocean and Polar Affairs Bureau of Oceans and International Environmental and Scientific Affairs U.S. Department of State, “Limits in the Seas, No. 143, China: Maritime Claims in the South China Sea”, December 5, 2014. http://www.state.gov/e/oes/ocns/opa/c16065.htm.

[8] Op Sit, “Limits in the Seas, No. 143, China: Maritime Claims in the South China Sea”.

[9] Robert Beckman, “South China Sea Disputes Arise Again”, The Straits Times, 06 Jan 2020. https://www.straitstimes.com/opinion/south-china-sea-disputes-arise-again.

[10] Op Sit, “Limits in the Seas, No. 143, China: Maritime Claims in the South China Sea”.

[11] CLCS, “Outer limits of the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles from the baselines: Submissions to the Commission”. https://www.un.org/Depts/los/clcs_new/submissions_files/submission_mysvnm_33_2009.htm.

[12] Op Sit, “Limits in the Seas, No. 143, China: Maritime Claims in the South China Sea”.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Central Intelligence Agency, “The World Factbook, Spratly Islands”. https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/spratly-islands/#:~:text=The%20Spratly%20Islands%20consist%20of,by%20Malaysia%20and%20the%20Philippines.

[15] United Nations, “UNCLOS, Article 121”. https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/part8.htm.

[16] Op Sit, “Limits in the Seas, No. 143, China: Maritime Claims in the South China Sea”.

[17] Carl Sandburg, “Goodreads”. https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/918291-if-the-facts-are-against-you-argue-the-law-if.

[18] US-China Economic and Security Review Commission, “China’s Island Building in the South China Sea: Damage to the Marine Environment, Implications, and International Law”, 04 December 2016. https://www.uscc.gov/research/chinas-island-building-south-china-sea-damage-marine-environment-implications-and.

[19] Japan Ministry of Defence, “China’s Activities in the South China Sea”, March 2024. https://www.mod.go.jpend_actsec_envpdfch_d-act_b.pdf.

[20] Op Sit, Central Intelligence Agency, “The World Factbook, Spratly Islands”.

[21] Ely Ratner, “Course Correction: How to Stop China’s Maritime Advance”, Foreign Affairs, July/ August 2017: Volume 96, Number 4. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/course-correction.

[22] Op Sit, Japan Ministry of Defence, “China’s Activities in the South China Sea”.

[23] Andrew S. Erickson and Austin Strange, “Pandora’s Sandbox: China’s Island-Building Strategy in the South China Sea”, Foreign Affairs, 13 July 2014. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2014-07-13/pandoras-sandbox.

[24] Lynn Kuok, “The U.S. FON Program in the South China Sea: A lawful and necessary response to China’s strategic ambiguity”, Centre for East Asia Policy Studies at Brookings, East Asia Policy Paper 9, June 2016. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/the-us-fon-program-in-the-south-china-sea.pdf.

[25] US Dept of State, Bureau of Oceans and International Environmental and Scientific Affairs, “Limits in the Seas, No. 117, Straight Baseline Claim: China”, 09 July 1996. https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/LIS-117.pdf.

[26] Robert B. Zoellick, Deputy Secretary of State, “Whither China: From Membership to Responsibility?”, Remarks to National Committee on U.S.-China Relations, New York City, September 21, 2005,

US Department of State Archive. https://2001-2009.state.gov/s/d/former/zoellick/rem/53682.htm.

[27] William Wan, “Hillary Clinton, Top Chinese Officials Air Some Differences”, The Washington Post, 5 September, 2012. http://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/hillary-clinton-top-chinese-officials-air-some-differences/2012/09/05/78487e86-f746-11e1-8253-3f495ae70650_story.html.

[28] Peter Harris, “The Imminent US Strategic Adjustment to China”, The Chinese Journal of International Politics, Volume 8, Issue 3, Autumn 2015, Pages 219–250. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjip/pov007.

[29] The White House, Office of the Press Secretary, “Remarks by President Obama and President Xi of the People’s Republic of China in Joint Press Conference”, 25 September 2015. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2015/09/25/remarks-president-obama-and-president-xi-peoples-republic-china-joint.

[30] Op Sit, Ely Ratner, “Course Correction’.

[31] Op Sit, Lynn Kuok, “The U.S. FON Program in the South China Sea”.

[32] Jeff M. Smith, “An Innocent Mistake”, Foreign Affairs, December 3, 2015. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2015-12-03/innocent-mistake.

[33] Op Sit, Jeff M. Smith, “An Innocent Mistake”.

[34] Op Sit, “UNCLOS, Article 13”.

[35] Bonnie S. Glaser and Peter A. Dutton, “The U.S. Navy’s Freedom of Navigation Operation around Subi Reef: Deciphering U.S.Signaling”, The National Interest, 06 November 2015. https://nationalinterest.org/print/feature/the-us-navy%E2%80%99s-freedom-navigation-operation-around-subi-reef-14272.

[36] Raul Pedrozo and James Kraska, “Can’t Anybody Play this Game? US FON Operations and Law of the Sea”, Lawfare, 17 November 2015. https://www.lawfaremedia.org/article/cant-anybody-play-game-us-fon-operations-and-law-sea.

[37] Supreme Court of India, “Case No. : Appeal (civil) 13393 of 1996”, 23 September 2003. https://main.sci.gov.in/jonew/judis/19358.pdf.

[38] Testimony by Darshana M. Baruah, “Surrounding the Ocean: PRC Influence in the Indian Ocean, Serial No. 118–14”, Hearing before the Committee on Foreign Affairs, House of Representatives, One Hundred Eighteenth Congress, First Session, 18 April 2023. https://www.congress.gov/118/chrg/CHRG-118hhrg52142/CHRG-118hhrg52142.pdf.

[39] Ibid, Testimony by Jeffey Scot Payne.

[40] Rahul Karan Reddy, “China in the Indian Ocean region: Ports and Bases”, Organisation for Research on China and Asia, 06 July 2022. https://orcasia.org/article/296/china-in-the-indian-ocean-region.

[41] Ibid.

[42] Wikipedia, “EEZs in the Atlantic and Indian Oceans”.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Exclusive_economic_zone_of_India#/media/File:Map_of_the_Territorial_Waters_of_the_Atlantic_and_Indian_Ocean.png.

[43] Suthirto Patranobis, “China renames five seabed features in Indian Ocean Region”, The Hindustan Times, 12 April 2023. https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/chinese-navy-names-five-undersea-features-in-indian-ocean-after-musical-instruments-101681238321842.html.

[44] On 22 January 2013, the Republic of the Philippines instituted arbitral proceedings against the People’s Republic of China under Annex VII to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (the “Convention”). The arbitration concerned the role of historic rights and the source of maritime entitlements in the South China Sea, the status of certain maritime features in the South China Sea, and the lawfulness of certain actions by China in the South China Sea that the Philippines alleged to be in violation of the Convention. China adopted a position of non-acceptance and non-participation in the proceedings. The Permanent Court of Arbitration served as Registry in this arbitration.

[45] US Department of State, “Joint Statement from the Quad Foreign Ministers’ Meeting in Tokyo”, 29 July 2024. https://www.state.gov/joint-statement-from-the-quad-foreign-ministers-meeting-in-tokyo/.

[46] Helen Davidson, “China’s maritime militia: the shadowy armada whose existence Beijing rarely acknowledges”, The Guardian, 13 June 2024. https://www.theguardian.com/world/article/2024/jun/13/china-maritime-militia-explainer-south-china-sea-scarborough-shoal#:~:text=The%20militia%20has%20a%20long,and%20other%20competing%20claimant%20nations.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!